In early twentieth-century Vienna, Gustav Klimt (Baumgarten, 1862 - Vienna, 1918) was a protagonist as well as the founder of the Vienna Secession, that association of nineteen artists who wanted to break away from the Viennese academic tradition in order to rethink the work of art itself as a total work of art that included architecture, sculpture, painting and design. In those years another painter, thirty years younger than Klimt, Egon Schiele (Tulln an der Donau, 1890 - Vienna, 1918), also participated in the movement of great artistic renewal and was significantly fascinated by the latter’s art. However, as Patrick Bade points out, “Klimt belongs to the transitional era of the late 19th century,” while Schiele represents “the beginnings of that movement belonging unmistakably to the early 20th century that was Expressionism.” Unlike Klimt, whose works are characterized by dreamy, delicate features and often by the presence of colorful flowers accompanied by mosaic elements, Schiele’s works are an expression of a tormented psyche. A relationship of deep esteem and friendship arose between the two, even though their styles were very different: Schiele was at first inspired by the art of his friend and master, but then he quickly abandoned its typical artistic traits, from sinuous lines to gilded decorations, and moved closer to a cruder and more real style, clearly visible in the depiction of human figures, especially in portraits, self-portraits and female nudes.

Expressionism, a movement that originated in Germany at the beginning of the twentieth century and then spread throughout Europe in all the arts, from figurative arts to music, theater, and film, denoted an artist’s tendency to exalt the inner, emotional side with a certain dramatic flair, contrasting with Impressionism, which on the contrary looked at the outer world: a kind of inner unease that Schiele expressed through deformed bodies and figures, nervous lines, and strong, violent colors such as red, brown, earthy hues, black, and pale yellow. This unease was primarily social in nature, a symptom of a critique of society and authorities, particularly the academic tradition and the state. Psychological introspection and that feeling of inner uneasiness in relation to the outside world were in fact particularly heartfelt themes at the time, thanks to the advent of the revolutionary theories of Austrian physician Sigmund Freud (Freiberg, 1856 - Hampstead, 1939), founder of psychoanalysis, according to which the unconscious has a decisive influence on human behavior and interactions between individuals. Art, too, is invaded by this particular focus on the self and the psyche, as are all fields of knowledge. It is in this context that the art of Egon Schiele fits.

Born in a small town in Austria, in Tulln, near Vienna, in 1905, when he was only 15 years old, he was orphaned by his father, who was a stationmaster by trade. Egon’s passion for drawing manifested itself from an early age, when he would spend hours drawing the trains he saw passing beneath his house every day, as he lived with his family in an apartment above the train station. His father, Adolf Schiele, suffered from mental disorders due to syphilis, which led to his tragic death. This fact probably already influenced Egon’s artistic thinking and vision. His uncle, Leopold Czinaczek, took his nephew under tutelage and it was he who recognized his artistic talent, so he enrolled him in theAcademy of Fine Arts in Vienna. The academic environment, however, was not congenial to Schiele as the teachings were too close to tradition, and here Egon felt compelled to draw and paint according to the old masters. However, it was in 1907 that he made the encounter that changed his life: in a café in Vienna he met Gustav Klimt, who introduced him to the artistic milieu, introducing him to wealthy patrons and procuring several models for him to portray in his paintings. Klimt became his teacher and mentor, helped him develop his own style, far from academicism and especially marked by personal events and social context, at odds with institutions. The following year, in 1908, the young Schiele held his first solo exhibition for the Wiener Werkstätte, an art circle founded in 1903 by architect Josef Hoffmann and graphic designer and painter Koloman Moser in collaboration with industrialist Waerndorfer that was based on the idea of the total work of art, introducing objects of high aesthetic and artistic value into everyday life.

Already in his early works one can recognize in Schiele an expressionist style with a particular flair for depicting nudes, where even sexuality and eroticism appear distorted and full of anguish (they are often combined with the themes of death and illness; an example of this is the painting preserved at the Belvedere in Vienna in 1915, Death and the Maiden), but also portraits of acquaintances and self-portraits. Seeing critical success, he decided to leave the Academy of Fine Arts in 1909 and to found with fifteen other artists the Neukunstgruppe, established to spread new forms of artistic expression in Vienna that were far removed from the principles of the Academy. After exhibiting at the Kunstschau and Galerie Prisko, the latter of which was also visited by Archduke Franz Ferdinand, he moved in 1910 to the small town of Krumau with model Wally Neuzil, with whom he had a love affair: the inhabitants of the small Bohemian town criticized the fact that the two lived together since they were not married, and in addition they maliciously viewed the fact that Schiele portrayed very young models for his nudes; because of this hostile climate they moved to Neulengbach,in the Vienna Woods. Even two years later, the artist was accused of seducing a not-yet-14-year-old girl, the daughter of a naval officer, of leading her astray and even kidnapping her: he then ended up in prison for a short time, with the “aggravating circumstance” of having portrayed young girls, on the verge of adolescence, naked. Works that at the end of the trial were deemed pornographic. The experience of imprisonment marked the artist even more. He therefore decided to return to Vienna, and thanks to his friend Klimt, he was able to obtain important commissions again, returning to success.

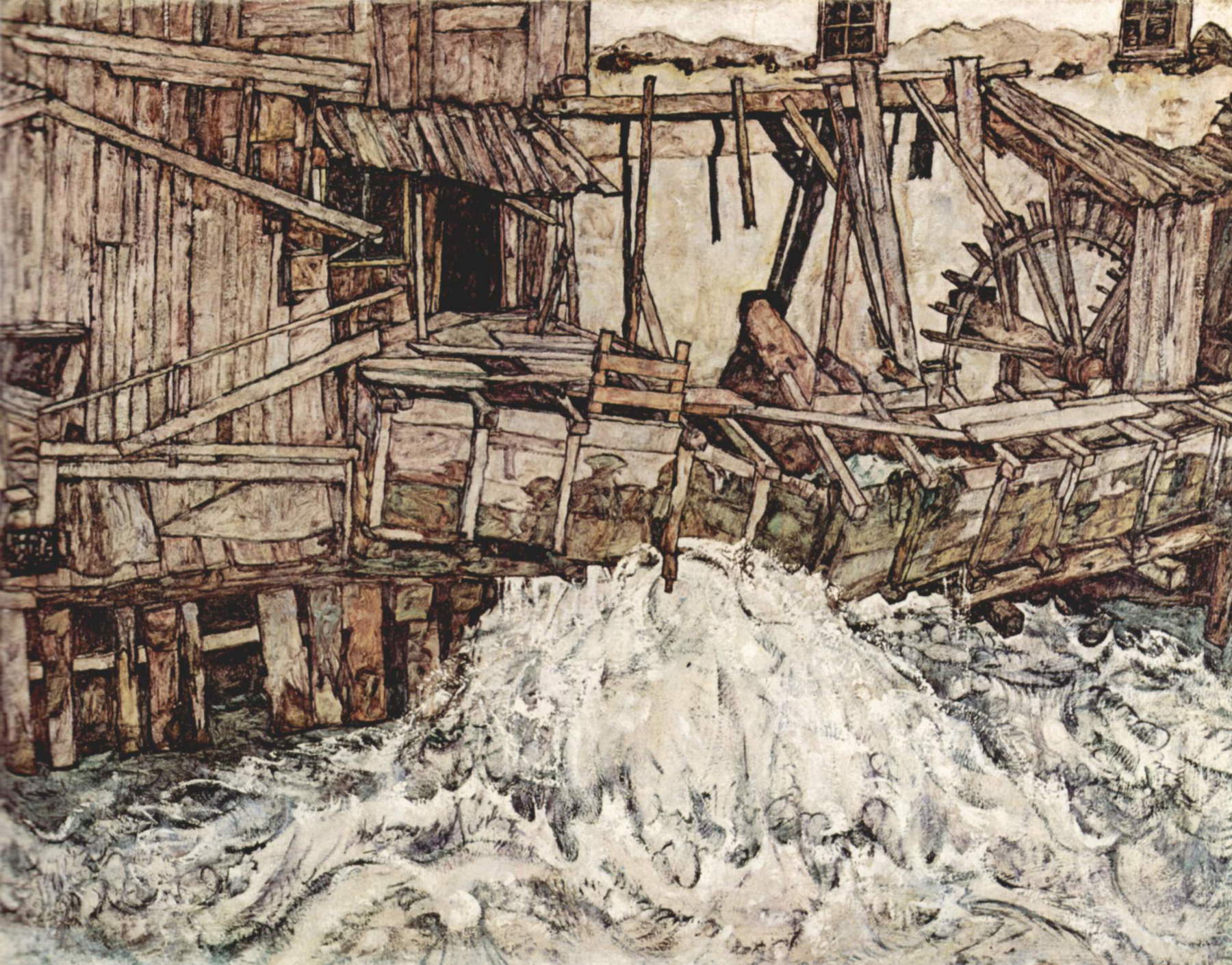

In 1914 he was united in marriage with another of his models, Edith Harms, from then on his only muse (among the most famous portraits of his wife is the 1917 portrait preserved at the Národní galerie in Prague): in fact, he left Wally forever, who would later die at the front as a Red Cross nurse. At the outbreak of World War I Schiele was called to arms, but thanks to his artistic talent he was able to continue painting, avoiding going to the front lines. One of his most famous works dates from this period, 1916: The Old Mill, now housed in the Niederösterreichisces Landesmuseum in Vienna. The mill falling apart due to the force of the water is symbolic of the decadence of Austrian society at the turn of the century and the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which, following the end of World War I, would be dismembered two years later. In 1918 he participated in a major retrospective related to the Viennese Secession, and on this occasion he was again successful, but this year marked the death first of his wife, who was six months pregnant, from the Spanish flu epidemic and, a few days later, also the demise of the artist, who also failed to save himself from the contagion. In fact, he died three days after his wife, on October 31, 1918, at only twenty-eight years of age.

Despite his early death, Egon Schiele was a very prolific artist: in the course of his work he produced about three hundred and forty paintings and two thousand eight hundred watercolors and drawings. The Leopold Museum in Vienna, located within the MuseumsQuartier and originating from the collection of Rudolf Leopold (1925 - 2010), holds the world’s largest and most important collection of the artist’s work: forty-two paintings, one hundred and eighty-four original graphic works, including drawings and color sheets, and autograph documents trace his entire career. Among Schiele’s major masterpieces on display at the Leopold Museum are theSelf-Portrait with Alchechengi and the Portrait of Wally Neuzil: when viewed together, these two paintings look as if they are the pendant of each other. Both completed in 1912, when therefore the two were cohabiting, united by a love affair, the two paintings present the same setting: both on a white background and in the foreground the half-bust of the two lovers. In theSelf-Portrait with Alchechengi, a perennial plant that produces small edible red berries, Egon Schiele depicts himself in the foreground with his face almost three-quarter-length, his neck slightly bent, his shoulders in a non-symmetrical position and a black garment, as he looks at the viewer from the side. Behind him thealchechengi, also bent and with a dark stem, in a kind of comparison between plant and artist. Probably both connected to the theme of fragility, of being bent to events. Often in order to self-represent himself Schiele would stand in front of a mirror and through his gaze try to go beyond it, penetrating into the depths of his self: thus a kind of mirroring of his interiority was created in his paintings, since through the mirror he shows himself to himself and at the same time the viewer perceives in the portrait all the artist’s emotional charge and anguish. If in theSelf-Portrait Schiele is tilted to the right of the viewer with the alchechengi visible on the left, specularly in his portrait Wally bends his head to the left of the viewer, while on the right a branch is also visible. The viewer is inevitably enraptured by the girl’s large blue eyes; the face is quite angular with red lips and slightly flushed cheeks, as reddish is her close-cropped hair. Wally, like Egon, is also portrayed in a black dress, adorned with a white collar. Two portraits that are very similar, both longing to be heard and understood with all their emotional baggage.

Themelancholic and suffering soul clearly visible in his portraits can also be perceived in his landscapes, shrouded in a gloomy melancholy. They are landscapes in most cases lonely and deserted, expressing the cyclical nature of life through faded flowers, bare trees, the sunset. Schiele “ascribes something human to the landscapes,” as Leopold Museum curator Verena Gamper points out. And very often they are charged with disturbance.

Considered to be a very provocative painter bordering on pornography, Egon Schiele was, on the contrary, one of the most introspective artists of the 20th century, able to convey through both his numerous self-portraits and landscapes his sensitive and melancholy nature, marked by the hardships produced by the society and the era in which he lived.

To find out more about Schiele’s figure and places: https://www.austria.info/it/arte/artisti-e-capolavori/egon-schiele-splendidi-paesaggi-malinconici

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.