To remember the figure of Gillo Dorfles (Trieste, 1910 - Milan, 2018), who passed away the day before yesterday in Milan at the age of 107, we propose one of his readings of the art of Lucio Fontana (Rosario, 1899 - Comabbio, 1968): these are two chapters taken from the volume Critical Preferences. A look at contemporary visual art published in 1993 by Edizioni Dedalo. The second chapter, “Fontana in Zagreb,” published in the same volume, is taken from the catalog of Lucio Fontana’s exhibition held at the Moderna Galerja in Zagreb in 1982. The images, added by the editors of Finestre Sull’Arte, are not part of the original text.

Fontana: the holes and cuts

From his youthful years Fontana despised the easy ways that lead to immediate success and often destroyed with his own hands the glorious pedestals he had established. He could have rested in the easy wake marked by Adolfo Wildt - his first teacher - or developed the address of a Martini; instead he was able to abandon every old tradition in search of a new path to trace.

The alternative between the purity of a spatial search free from all metric allurements, and a voluptuous and almost sensual creation of neo-Baroque silhouettes, can be considered the basis of his creative will: It would be wrong, therefore, both those who believe that they have identified Fontana only in the “painter of holes and cuts,” in the artist who was able to free himself from the complacencies of tone and impasto; and, even more, those who would limit themselves to seeing in him the shaper of “pleasant” decorated ceramics used as ornaments for bourgeois drawing rooms.

Recently Fontana - after composing a series of very pure canvases where only the immediate and dazzling gesture of the cuts affixed an irreplaceable signature to the painting - had the sudden impulse to carve a clear and peremptory mark on the still virgin surface of a sphere of clay cut into two “slices.”

The result was “spatial expectations” that have the fleshy voluptuousness of androgynes just as Plato described them to us in one of his dialogues: bodies, almost human, created in the primal clay, that same clay of which man was fashioned, and which - torn into two identical valves - were engraved by the creator’s cut, unique and duplicitous, living emblems of a bisexuality that can only be fulfilled by reunion. Well, in these plastic “spatial waits,” the artist reveals his constant ability to renew himself and to rediscover-even in periods of the most distilled compositional chastity-that sensual and magical impulse without which man will never be able to become an authentic creator.

I have not forgotten the impression made on me - in the years between ’31 and ’35 - by a sculpture such as “The Lovers” for the Saturday House at the Milan Triennale, or certain graphics in black and white cement. This was one of the first Italian rebellions against the equivocal twentieth-century monumentalism, and it was also one of the first attempts to introduce color into plastic.

The period, which we can call “of the black statues,” marked an important turning point in Fontana’s work, and consisted of a series of plaster or concrete statues treated with an elementary and meager technique and made more “aggressive” by a sober chromatization that made use almost exclusively of a few basic colors: black, white, gold, silver, and red. Perhaps the lesson of an Archipenko, and an Arp, and even that of a Zadkine (especially for the “black statues”) was not entirely unimportant at that time. Yet, already in these early attempts, his personality is clearly identifiable and autonomous.

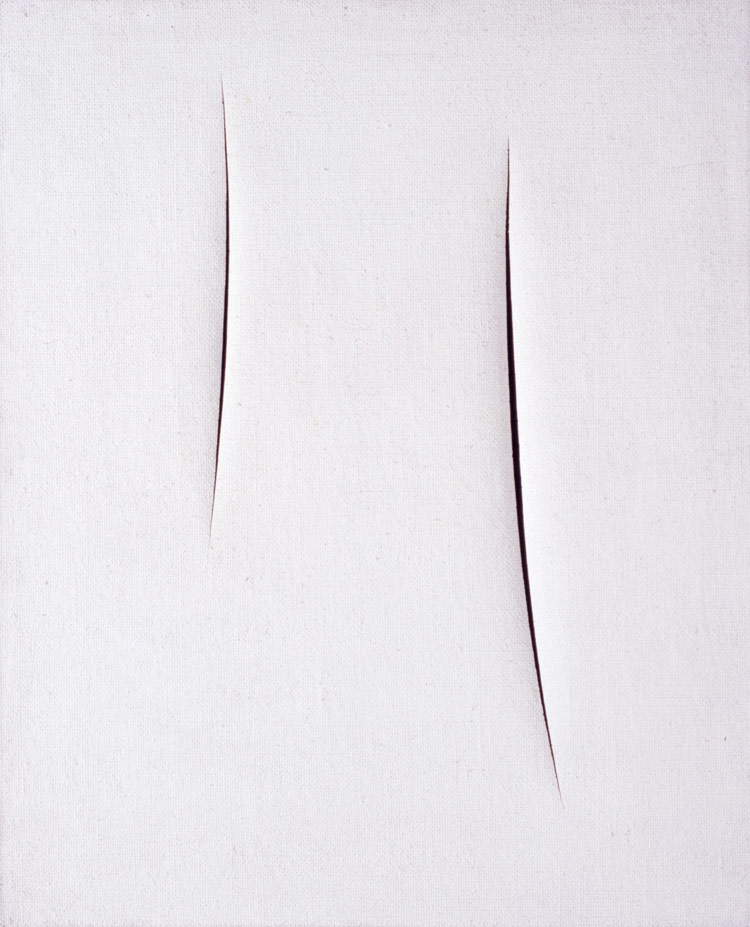

|

| Lucio Fontana, Spatial Concept. Waiting (1959; watercolor on canvas, 100 x 81 cm; Rovereto, MART - Museo di Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto, on deposit from private collection; © Lucio Fontana Foundation) |

|

| Lucio Fontana, Spatial Concept. Nature (1959-1960; terracotta, 40 x 55 x 46 cm; Private collection; © Lucio Fontana Foundation) |

It often fell to Fontana to be the forerunner of new artistic currents; often one of his technical “gimmicks,” one of his rhetorical inventions, anticipated a later fashion by many years; so that Fontana often had the unwelcome surprise of seeing other artists become known for “inventions” whose priority was his.

This was the case, for example, for some paintings based on a rough and rough material, or canvases based on black surfaces - alternating matte and glossy - that had almost immediately a host of followers and imitators.

While the first impetus to what was later called “spatialism” actually dates back to 1946 (when Fontana had drafted together with a group of Argentine artists the “Manifesto Blanco”), it must nevertheless be acknowledged that the birth of this movement must be placed at the time of the artist’s return from Argentina (where he had gone to escape fascism and war and where he was born) and his first exhibitions based precisely on the search for an art that was extended beyond the limits of the canvas or the individual sculpture.

It is symptomatic that Fontana, already around 1947, felt the urgent need to proclaim the inadequacy of the “easel painting,” of the distinction between painting and statue, and felt, on the other hand, the importance of creating an art capable of transcending the narrow limits of the surface of the canvas to extend into a broader dimension, such that it would moreover become a “creator of atmosphere,” an integrator of architecture, a future art “transmissible in space” by means of the new discoveries of science and technology. Thespatial art of which Fontana reasoned (and do not forget that in those very years the artist had also approached the works of the other Milanese group: the MAC, founded in 1948 by Munari, Soldati, Monnet and Dorfles) included not only painting and sculpture but also television broadcasting, luminous graphics, “spatial” plastic.

A singular example was the large neon tube light ribbon, exhibited at the IX Triennale, which was one of the first exemplifications of a plastic-architectural intuition. Already at the 1958 Biennial, when most of the artists were presenting their paintings ingrommatized with dense chromatic matter, Fontana had a room where the canvases appeared barely veiled by a thin inking, often monochrome, or where the superimposition of two thicknesses - quite different from the complicated collages of the many other artists - created that subtle slivelling sufficient to mark the presence of a different spatial dimension. That was the period when Fontana’s work came closest - but only apparently - to Rothko’s. Rothko, too, had for years and years - renounced the allurements of large matter, - pursued a purification of pictorial means that led him to the creation of immense surfaces where color once again became “atmosphere,” no longer naturalistic, but spiritual.

Fontana - renouncing the concretions and trappings of sequins and fragments of glass (which he had “sown” on certain canvases from 1952 to 1954) - returned to being that sober artist who only rarely transcends into the arbitrariness of hedonistic decoration.

I would now like to dwell at least for a moment on what remains Fontana’s happiest productive epoch, and which can undoubtedly be defined as the epoch of holes.

The “holes” are both signs capable of fixing a compositional trace, a two-dimensional drawing, and of constituting a plastic and volumetric structuring. The presence of an incision and an “absence” of matter, causes the two-dimensional spatiality of the canvas to be interrupted and to let the emptiness behind emerge, projecting toward the nothingness in front. In addition to this, the holes, made with that “speed of impulse” that characterizes them, have the immediacy and irrevocability of an absolute sign and give the canvas - often monochrome, even white -, a relief not otherwise attainable. From all this it is easy to understand how the use of holes could also be extended to vast surfaces, to walls, to ceilings, becoming in that case rather an element of plastic-luminous decoration than a real “painting.” But Fontana-not wrongly-has always insisted on the importance of no longer considering the “painting” and the “statue” as the two essential goals of visual art today and in the future: in order to survive, painting and sculpture must not only integrate with architecture, but must acquire a “stature” that is no longer merely that of the easel painting and the ornament.

After the fundamental period of the holes and that of the cuts, another episode was that of the “quanta”: canvases of irregular shape and size, often trapezoidal beaten by the usual cuts and arranged in a highly varied order-disorder next to each other so as to create on the wall a kind of unpredictable constellation.

It is an experiment that had in part already been attempted by Frederik Kiesler. But whereas the old Americanized Viennese architect meticulously calculated the mutual positions at which his compositional fragments were to be situated, for Fontana these compositions were empirical and free. That is, Fontana intuited one of the principles toward which much of today’s art is being oriented, not only in painting, that is, that of thealeatory work, to which the interpreter (or the viewer) must (or can) add something; thework in the making not yet concluded that can be integrated, that can acquire new aspects through subsequent manipulation by the artist, the viewer or even by chance. Just as Calder’s or Munari’s furniture acquires different aspects depending on the oscillations impressed by the wind, so do Tinguely’s machines “participate” in the creation of partially involuntary signs, or as - in music - Stockhausen’s now famous Klavierstück XI consists of a series of musical fragments that can be begun and performed by the performer ad libitum, starting the performance from any point, or as in other compositions by Pousseur and Boulez where it is up to the performer to decide the rhythm, duration, and intensity of a sound sequence.

|

| Lucio Fontana, Structure for the 9th Milan Triennale (1951; crystal tube with white neon; © Lucio Fontana Foundation) |

|

| Lucio Fontana, Spatial Concept. 62 O 32 (1962; oil, slashes and graffiti on canvas, 146 x 114 cm; Milan, Fondazione Lucio Fontana; © Fondazione Lucio Fontana) |

|

| Lucio Fontana, Spatial Concept. The Quanta (1960; nine elements in watercolor on canvas; Milan, Fondazione Fontana; © Fondazione Lucio Fontana) |

Fontana in Zagreb

Those who have known Fontana since his early Milanese period around the 1930s, like the writer, and have followed his diverse and unexpected creative stages, know that the artist personified like few others the figure of the spontaneous creator far removed from all cerebralism.

Fontana has never been an intellectual, elucubrating laboriously almanacized inventions, nor a theorizer of complicated poetics that are often inapplicable; instead, he has been the genuine inventor who never goes hunting for updates, but always finds, almost unbeknownst to him, new golden threads to exploit. His dynamic drive, infectious joviality, and inexhaustible helpfulness have become proverbial, almost legendary. Always ready to help friends and simple acquaintances, ready to buy the little painting of the poor artist, to “make an exchange” of one of his already valuable paintings (in his last years) with that of any beginner - probably destined to remain so - who proposed him “the deal”; ready to discuss with impetus and passion causes lost at the start; to defend the young avant-garde in the juries of the Triennale and Biennale...

I believe that these few annotations around the Fountain-man, and his little coquetries in choosing a tight overcoat, a hat with a raised wing, a pair of suede shoes, a gaudy tie, his predilections for certain foods, certain environments, the love with which he had rebuilt his father’s house in the Lombardy countryside, etc., etc., are not indifferent and useless for those who want to understand his work and thought. It is only in this way that we can understand the why of his discoveries: of the “holes” and “cuts”; of the little theaters, and the collages, of the hanging statues and “quanta,” of the “Natures” and “Spatial Expectations”; which constitute some of the many stages of his creative activity.

The impulse, for example, to puncture the canvas, to destroy, but building in other matter, the surface that has now become a slave to tradition, is a kind of impulse that would have been unthinkable in someone who was not endowed as he was with that sense of security even in the absurd of which, on the other hand, cerebralized artists, the theorizing, conceptualizing artists are almost always deprived.

When, to give just one example, Fontana decided to christen certain of his oval, monochrome compositions like large Easter eggs “End of God,” I remember that - having to present the exhibition - I invited him to change that title because it seemed vaguely irritating and at the same time too magniloquent.

Fontana at first listened to me - though he continued in private to call that series of works that - and exhibited them under the usual title of “Spatial Expectations.” Yet, I myself later had to see that his initial idea was far from absurd thinking back to the fact that those canvases recalled giant ostrich eggs. Thus I was reminded of Albertus Magnus’ ancient saying, “Si ova struthionis sol excubare valet / Cur veri solis ope Virgo non generaret?” (That is, “If the sun is able to make the ostrich’s eggs hatch, why could not the Virgin have generated by the true sun?”). Which demonstrated precisely the kinship between the immaculate conception and the divine egg. From the ostrich egg, the transition to the Christ egg - to that same egg that hangs mysteriously on the head of the Virgin in Piero della Francesca ’s Annunciation (and which in times long past the Florentines hung in churches precisely on the occasion of Easter festivals) - was obvious. And so it was that - for no magical or religious reason - Fontana had hit the nail on the head, had invented a title that, all things considered, was appropriate, to the series of his oval canvases.

I could cite other examples of this singular quality of Fontana’s that I could not define except by the abused term “intuitive.” when, for example, Fontana spoke of images and compositions to be disseminated in space through television and other mass media, rather than through paintings and statues; when, to illustrate Venice in an exhibition at Palazzo Grassi, he had composed a series of works with a golden background-almost ancient Byzantine icons, beaten by the usual cuts-there was always at the bottom of his programmatic statements or seemingly unmotivated achievements, an actual discovery that would often be understood and appreciated only much later.

But, in continuing to ruminate around these marginal episodes, I would risk squandering my discourse in too easy anecdote. Instead, I would like to recall again the most important stations of his artistic journey, as they may appear to the visitor to the exhibition.

Here, after the pre-war abstract graffiti (1934-35) (among the first non-figurative works of Italian sculpture), and the polychrome and gilded terracotta statues; and after the very baroque sketch for the doors of Milan Cathedral (never executed) (and let us not forget in this regard the baroque component present in many of his ceramics, in many of his sculptures) he began the great post-war period, immediately after the formulation--which took place still in Argentina--of the “Manifesto Blanco” (1946); the manifesto that condensed some of the basic principles of his artistic creed.

Then, as Fontana invented (around ’48) the “holes” and, a couple of years later, the “cuts,” his activity thickened; the monochrome painting became a compulsory stage in his work, alternating with the painting enriched by insertions of pebbles and crystals, alternating with the holes to the cuts. This was followed by a brief season of abstract but vaguely landscape collages, where two or three layers of lightly toned canvases created a kind of atmosphericity, unusual in his usually decidedly timbral paintings.

But, as early as ’48, Fontana was constructing a series of those spatial environments of his that were to constitute one of his greatest anticipations of the art that immediately followed. The great neon tube serpentine at the IX Triennale (1951), the black spatial environment (in Wood’s light) at the Naviglio (1949); the one for the Palazzo del Lavoro in Turin (1961), those for Foligno (1967), for the XX Biennale in 1958, were to constitute the premises for a whole new direction in contemporary art: showing a new direction no longer only to the easel painting, to the statue alone, but to the global space, appropriately modulated: a new trait-d’union between plastic-visual parts and architecture.

Parallel to the creation of the spatial environments, there was also a non-return to sculpture (never abandoned altogether) with the large Natures, immense clay spheres struck by deep splits, almost embryos of mysterious creatures.

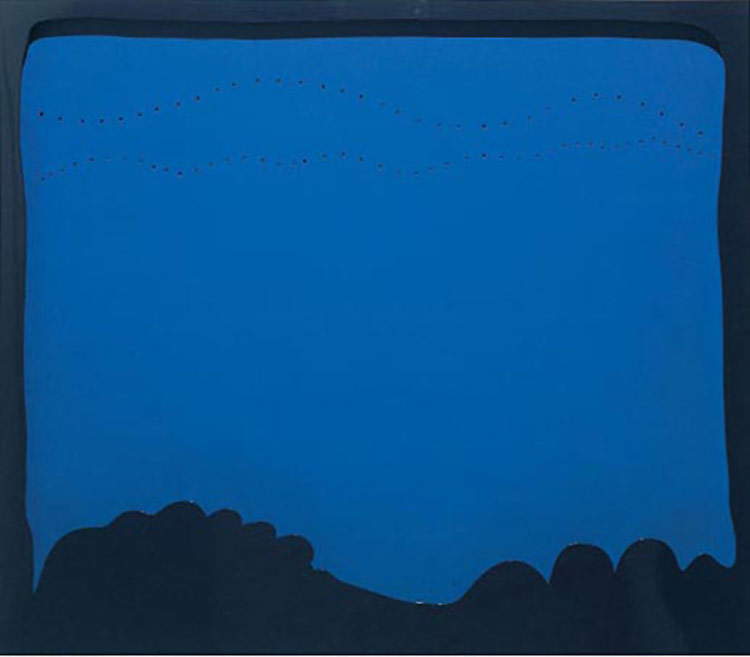

The very brief interlude of the “quanta” (1959) (paintings shaped in different forms and joined discontinuously to form a complex decomposable constellation) and then the wide range of the “teatrini,” where the polished and lacquered wooden frame (white, black, red, orange, etc.) acted as a jutting protagonist on the perforated curtain of the background.

With the teatrini (1963), with the series of metal paintings (copper, aluminum, painted sheet metal), with the numerous drawings, silk-screen prints, ceramics... the artist’s fertile and generous season came to a close.

|

| Lucio Fontana, Spatial Concept. The End of God (1963; oil and glitter on canvas, 178 x 123 cm; Madrid, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía; © Lucio Fontana Foundation) |

|

| Lucio Fontana, Spatial Environments in Black Light (1949; papier-mâché, fluorescent paint and Wood’s light for Galleria del Naviglio, Milan, 1949; installation view at the exhibition Lucio Fontana. Ambienti / Environments in Milan, Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, from September 20, 2017 to February 25, 2018; Courtesy Pirelli Hangar Bicocca © Fondazione Lucio Fontana) |

|

| Lucio Fontana, Fonti di Energia (1961; neon ceiling for “Italia 61,” Turin, 1961-2017; installation view at the exhibition Lucio Fontana. Ambienti / Environments in Milan, Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, from September 20, 2017 to February 25, 2018; Courtesy Pirelli Hangar Bicocca © Fondazione Lucio Fontana) |

|

| Lucio Fontana, Spatial Concept. Theater (1966; watercolor on blue canvas and dark blue lacquered wood, 143 x 166 cm; Milan, Marconi Foundation for Modern and Contemporary Art; © Lucio Fontana Foundation) |

Fontana - already sick at heart - nevertheless unwillingly gave up working, acting, participating in new art events, in a friend’s exhibition, always willing to help others, to encourage young and old “colleagues.”

Today, unfortunately, we are forced to “historicize” his work; to dissect it into epochs and periods; to critically investigate it by comparing it with that of imitators, epigones, followers.

We would at least like to hope that the freshness and spontaneity of this work is not destined to be stifled by the museification and commodification that, unfortunately, is always lurking in front of the original products of our time; and that the vividness of its message will remain so for the near and more distant future.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.