By now, Roberto Longhi ’s infamous anathema “Good night Mr. Fattori” hurled at the Macchiaioli and Giovanni Fattori has been cast aside. The Piedmontese critic had branded the Tuscan experience with provincialism, capable of producing only rhetorical and oleographic works, inhabited by poignant vedutines, resting Garibaldians and the pleasant countryside, recognizing the absolute dominance of the modern Parisian experience. And while to this day few would still go so far as to make the bold and unpopular choice of preferring the Macchiaioli to the Impressionist grouping, no one now disavows the merits to the Tuscan grouping. And indeed, the proliferation of exhibitions devoted to Macchiaioli artists indicates how they meet with public appreciation.

In this reappraisal, Giovanni Fattori’s role is known to any art lover, while the same cannot be said for the fundamental contribution he made to the greening of the modern Italian printmaking tradition, which he more than anyone else has to thank. This lukewarm critical fortune is probably attributable to two reasons: the first is that Giovanni Fattori’s graphic production is rarely seen, despite the fact that complete collections can be found at the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe in Florence, the University of Pisa, the Fattori Museum in Livorno, and the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo (works on paper are delicate, and often exhibiting them requires expedients and museum techniques that are not cheap, so much so that they are hardly ever found on display in the end). The other motivation is the condemnation that still hangs over the artistic technique of engraving, which, despite countless proselytes, is still included in the subset of the minor arts. But Fattori’s production with this technique certainly cannot be considered less than the large canvases with the battles of our Risorgimento, and the looser and freer paintings on small-format tablets, in which reality breaks into a circumscribed perimeter, for which the Leghorn artist is counted among the greats of art.

Specifically, in the field of printmaking, Leghornese confronted the technique of etching, a process on which a metal plate (usually copper or zinc) is cleaned, prepared and covered with wax, on which the artist engraves his drawing, and is then dipped in an acid mordant, to carve grooves in it. Finally, the plate is inked and thanks to a press the drawing impressed on paper.A complex technique of which “others certainly were more expert than he, if by expertise is meant patient exploitation of the little secrets of varnishing and biting, but no one of his time said a more definitive word, with such rough and sincere force,” commented the enlightened scholar and collector Lamberto Vitali about Fattori’s technique.

|

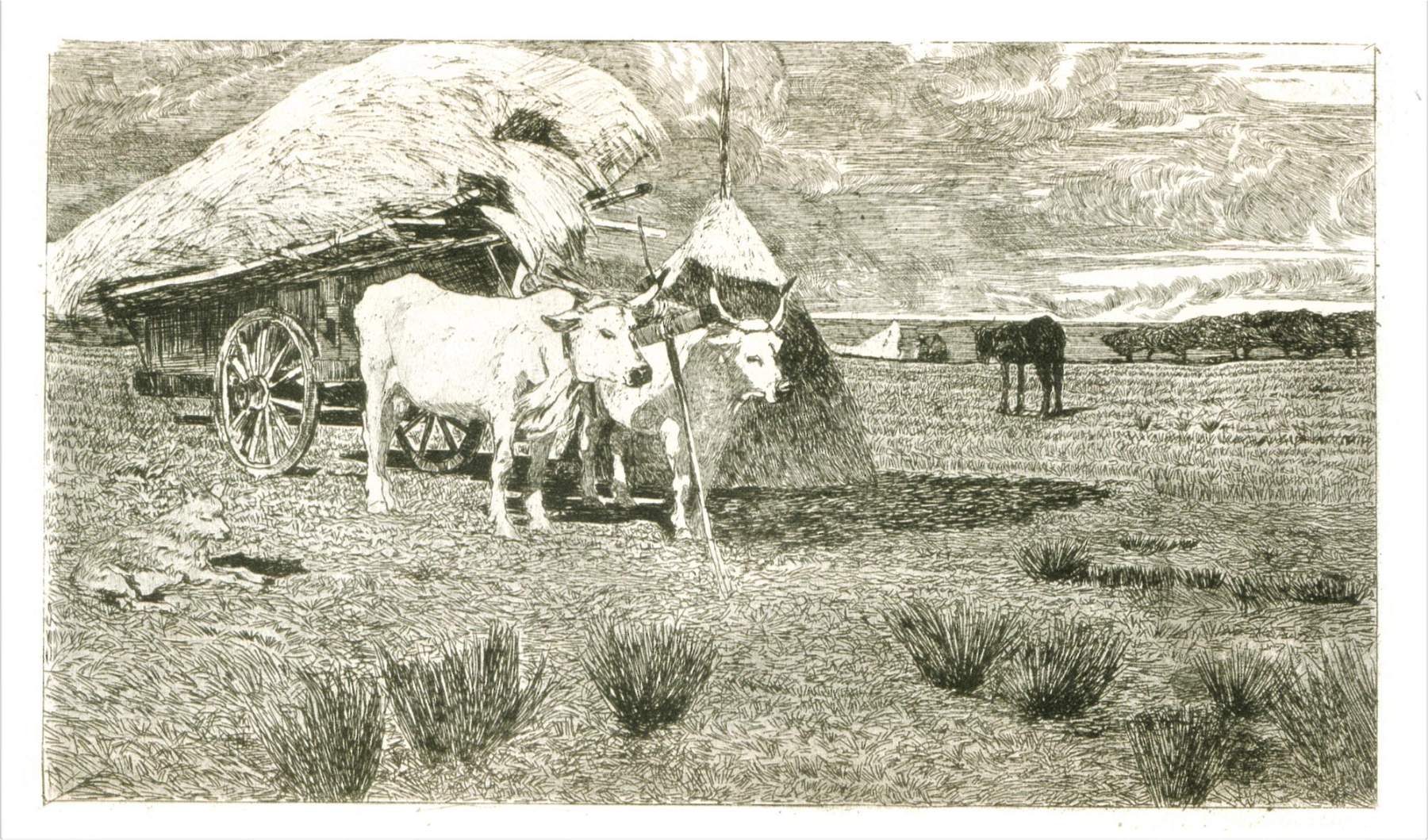

| Giovanni Fattori, Bovi al carro (Maremma) (1886 -1887; etching on zinc) |

|

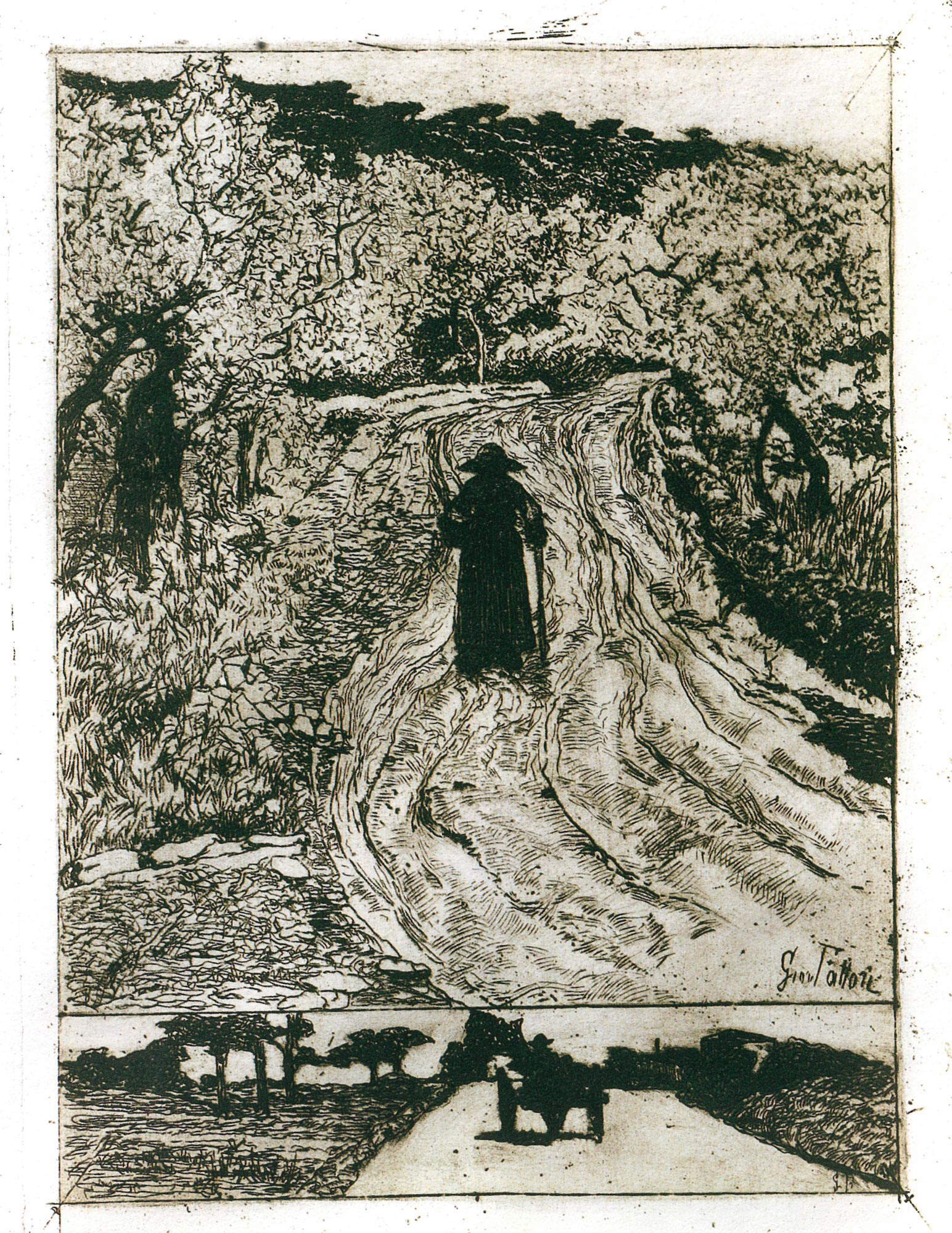

| Giovanni Fattori, Donna del Gabbro (pre-1888; etching on zinc) |

|

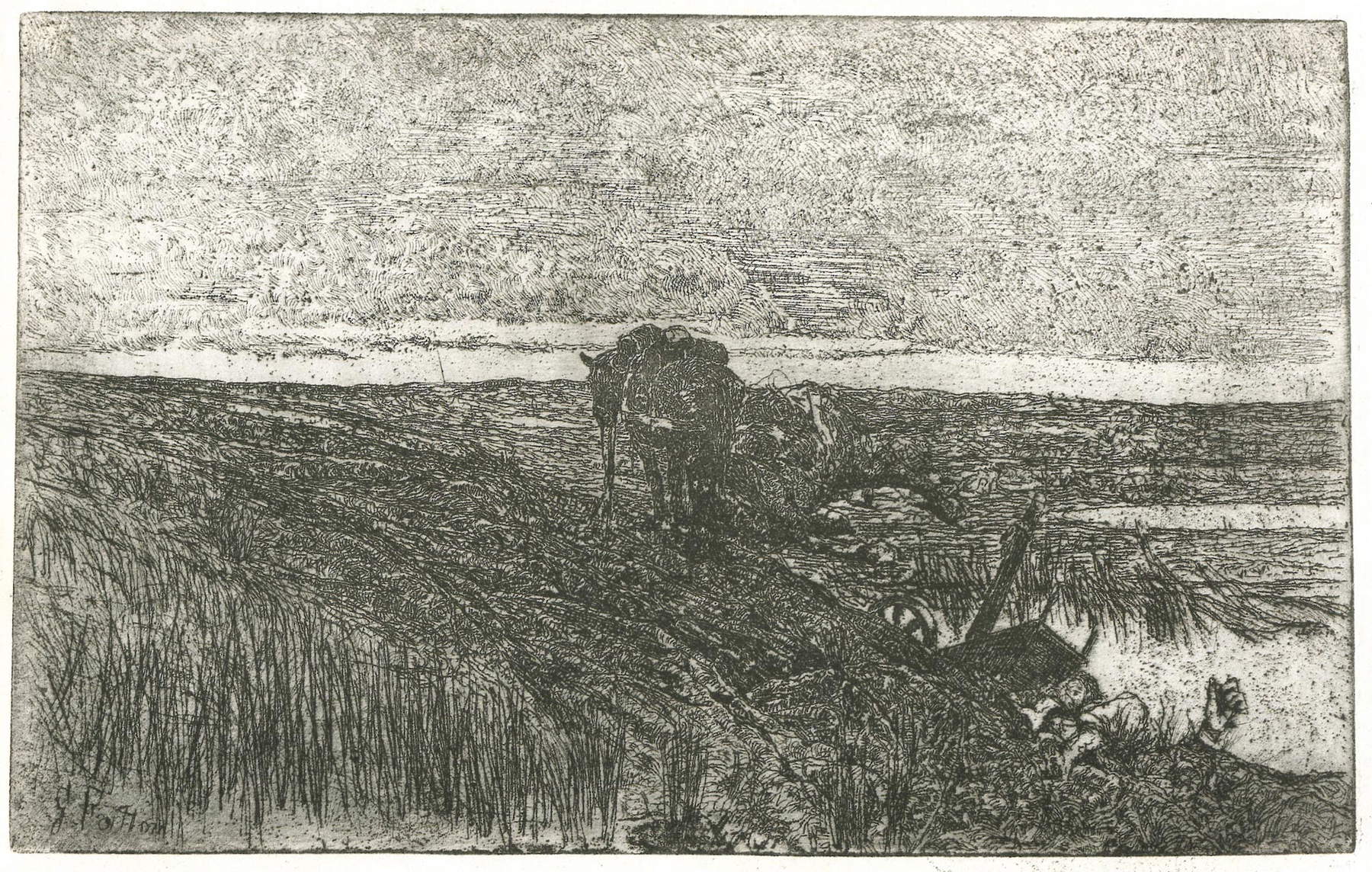

| Giovanni Fattori, Marsh (early 20th century; etching on zinc) |

|

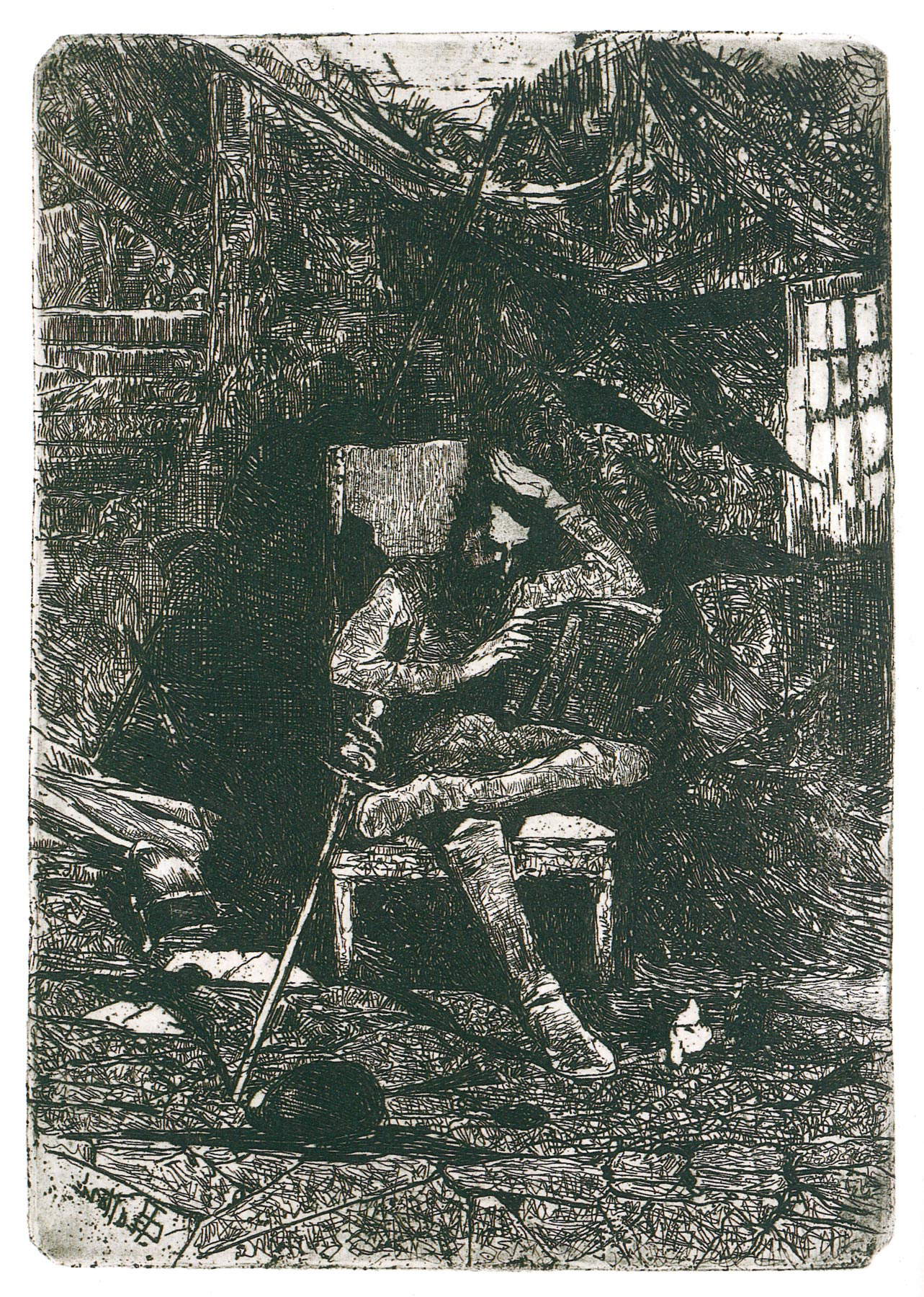

| Giovanni Fattori, Adua (early 20th century; etching on zinc) |

|

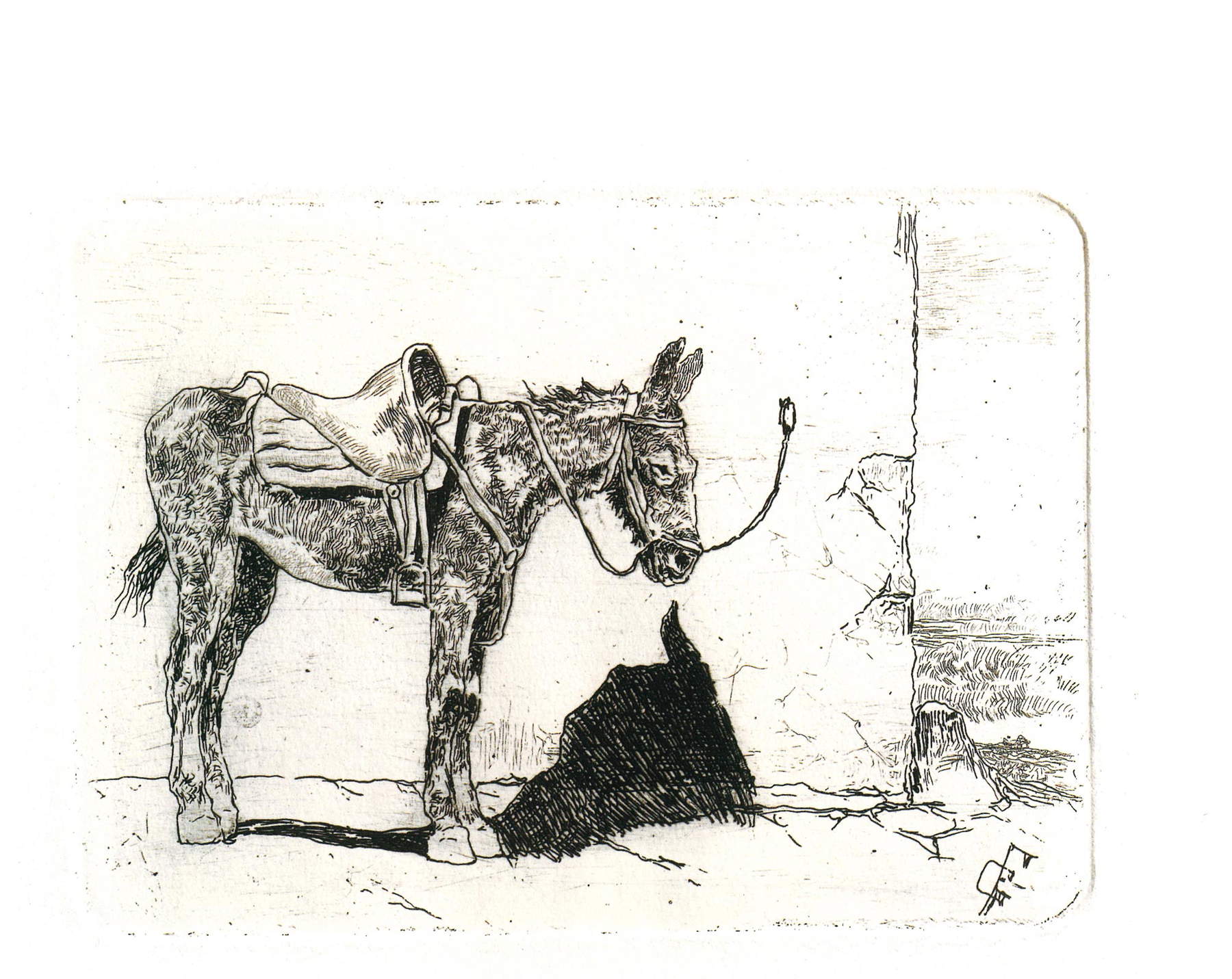

| Giovanni Fattori, Somarello in the sun (early 20th century; etching on zinc) |

Engraving activity for Fattori was not an episodic experience, but was constant throughout his creative parabola, and reconstructing this production chronologically is still an unresolved undertaking because of the few documents, and the prints that are almost never dated and numbered.The Tuscan artist must have become familiar with printed techniques as early as 1859, when, back in Livorno, he claimed in fact to have been “forced to make drawings on lithographic stones for newspapers” to support himself. But only at a mature age would he probe the expressive potential of etching with great exercise. In 1880 he was commissioned by the Fine Arts Society to translate into etching his famous painting Carica di cavalleria, housed in the Gallery of Modern Art in Palazzo Pitti: reason enough to believe that by that date Fattori’s talents as an engraver must have been widely known. While in 1888, 21 sheets exhibited at the National Exhibition in Bologna were purchased by the Ministry of Education for the National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome. In 1900 from Rome, unbeknownst to Fattori, the etching Bovi al carro (Maremma) was sent to the Universal Exhibition in Paris where it was awarded the Gold Medal. And it was on that occasion that, writing to Renato Fucini, the Leghorn artist said, “Excuse me, isn’t it laughable to see me medal and gold for etchings in etching? I etch, but who would have thought it?! everyone but me, and so much so that my plates stood on a closet in the dust to spoil and stain.”

This statement has in times past been interpreted by critics as evidence that Fattori held this production of his in low esteem, but rather it seems to answer to the image of a disinterested, uneducated, abstract artist, far from the art circuit, which Fattori built up throughout his life, keeping himself away from the spotlight or the persuasive sirens of European fashions. Later, he had an appointment as a member of the Artistic Commission of the Italian Chalcography (a position he held from 1901 to 1905).

Demonstrating that the continuous practice of engraving was not to be considered a mere refuge of the artist from his pictorial production, but rather a founding practice of his creativity, is also the date of some engravings, such as Due Amiciof 1907, executed when the painter was already very old and tired. There are more than 180 plates known to date, which he engraved and produced throughout the course of his mature life. Such production was therefore not a rest or an outlet for the Leghorn artist, rather “an irresistible need,” as Luigi Servolini wrote, “the need to complete his world, to interpret poetic reason.” Giovanni Fattori was undoubtedly aware of the value that this art held for the purposes of his artistic research, in the desire for an intimate expression of things, stripped of all that is accessory.

|

| Giovanni Fattori, Don Quixote (early 20th century; etching on zinc). Oscar Ghiglia owned a print of this that he was very fond of. |

|

| Giovanni Fattori, The Homecoming (early 20th century; etching on zinc) |

|

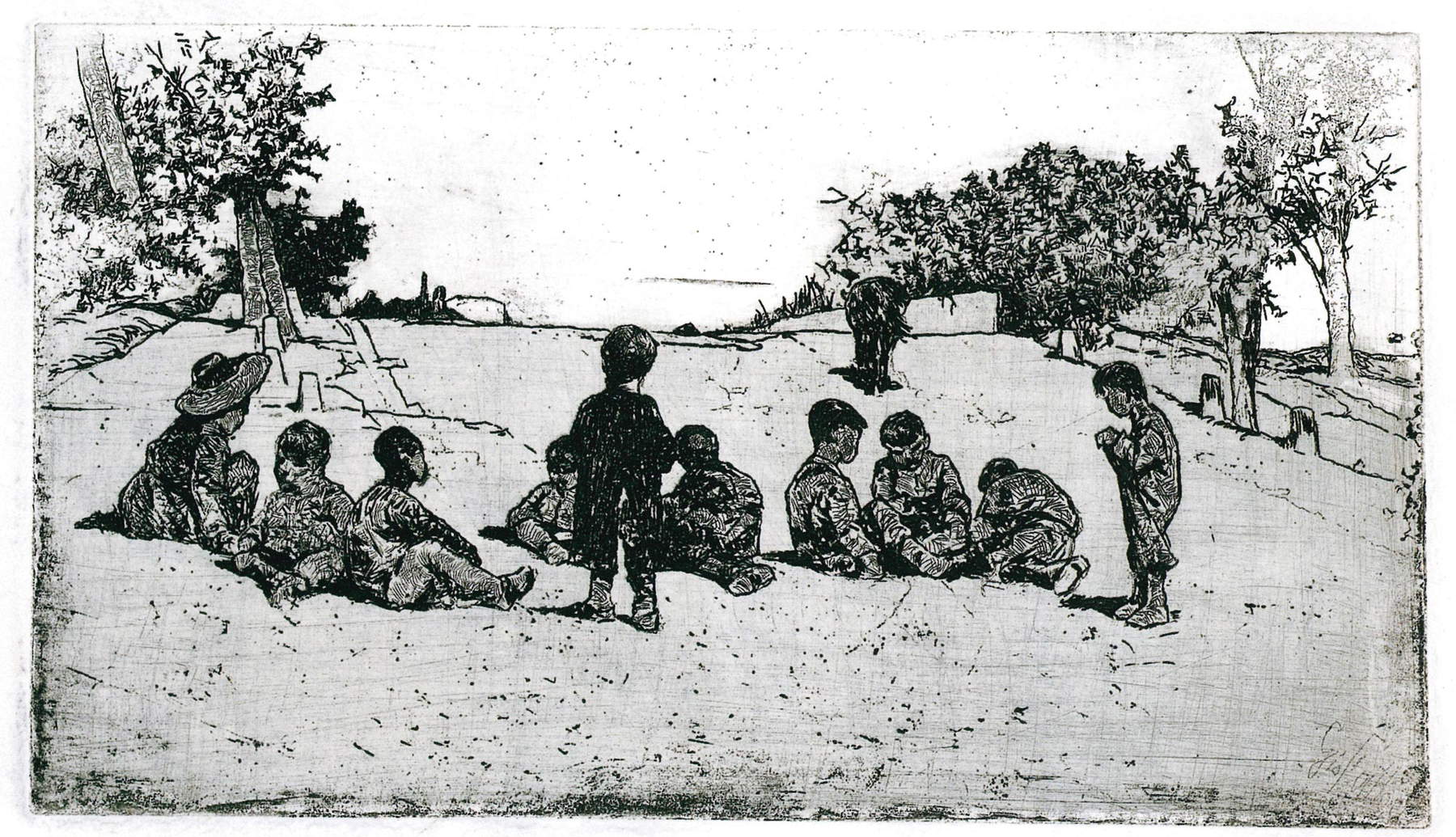

| Giovanni Fattori, Lora of Recreation (early 20th century; etching on zinc) |

The artist restores dignity to the graphic medium, recognizing an autonomy of its own to this technique, compared to artists such as Fontanesi and Signorini, who in confronting etchings always sought pictorial effects or literary references. Sometimes one has wanted to believe that the Macchiaiolo was unfamiliar with the etching technique, since not infrequently in his sheets one can see inaccuracies, paint detachments, and stippling due to faulty applications of varnish, or to an incorrect control of the morsura, or acid infiltration. But this, if anything, shows his idiosyncrasy for all norms and conventions. Fattori revolutionized the practice and understood the small sheet of metal not as was customary at the time, as a precious material to be entrusted with the ultimate and most studied work, but in the manner of a note sheet, carrying with it errors, the genesis of gesture and sign. It is even said that he carried the plates with him when he drew his impressions en plein air.

Especially in his early days, the artist printed on his own, with the help of faithful pupils, using the small hand press, given to him by Cristiano Banti, and which is now preserved at the Fattori Museum in Livorno. Thanks in part to this unconventional practice, the painter was able to create highly original works, where inaccuracies do not harm the whole, but often enhance it, so much so that one wonders if sometimes they were not intended by the master.

The subjects of his etchings are the same as those that crowd his paintings: those very fresh and spontaneous scenes of life in the purely agricultural Tuscany of the 19th century, which he sometimes repeats in both mediums, but always with different solutions. Landscapes sometimes bare and synthetic, built on a succession of calibrated planes, but also the life of toil, peasants, charcoal burners, the mighty butteri or animals exhausted by hard work, or even military maneuvers and scenes of life from the encampments. Snapshots that render Fattori’s need and expressive urgency, in which through instinct and his own sensitivity he rereads his subjects and evokes them with a vital energy, the result of his own personal reinterpretation. He entrusts everything to the sign, eschewing certain graphic and sinuous virtuosities in vogue in nineteenth-century engraving or chiaroscuro. The sign seems to emphasize the primal structure of things, stripping away everything superfluous and drying up the composition.

His continuous graphic exercise and natural disposition reveal to Fattori the secret of the bare and clean sign, which reinvents itself from time to time to adapt to communicative needs, but always orchestrated by a natural organic vision. Sometimes the works show a swarming of signs, which become sparse and calculated, others graduated in thickness, always with different gaits, parallel and sharp lines, or fat and grainy strokes, crossed in coils or resolved in tangles. Servolini argued that Fattori, unable to transpose the stain into etching, had entrusted the whole secret of his art to the sign. A sign that later in the 20th century would pave the way for many artists, from Boccioni’s graphics to Morandi and Viviani, and even the young Modigliani must have harbored a certain fascination for such a sharp and constructive stroke.

|

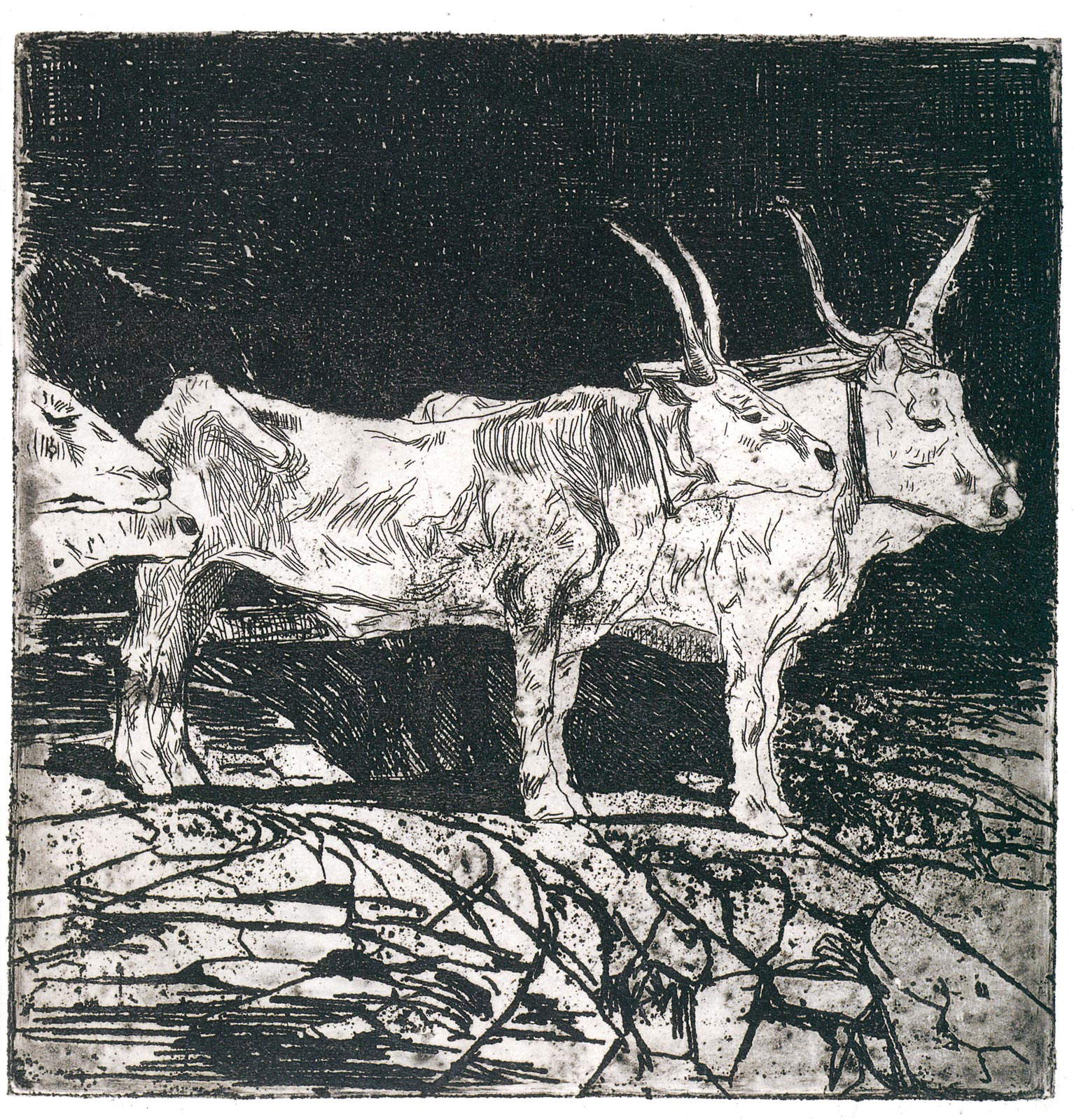

| Giovanni Fattori, Bovi (early 20th century; etching). According to Andrea Baboni, one of the most extraordinary etchings of the entire 19th century. |

|

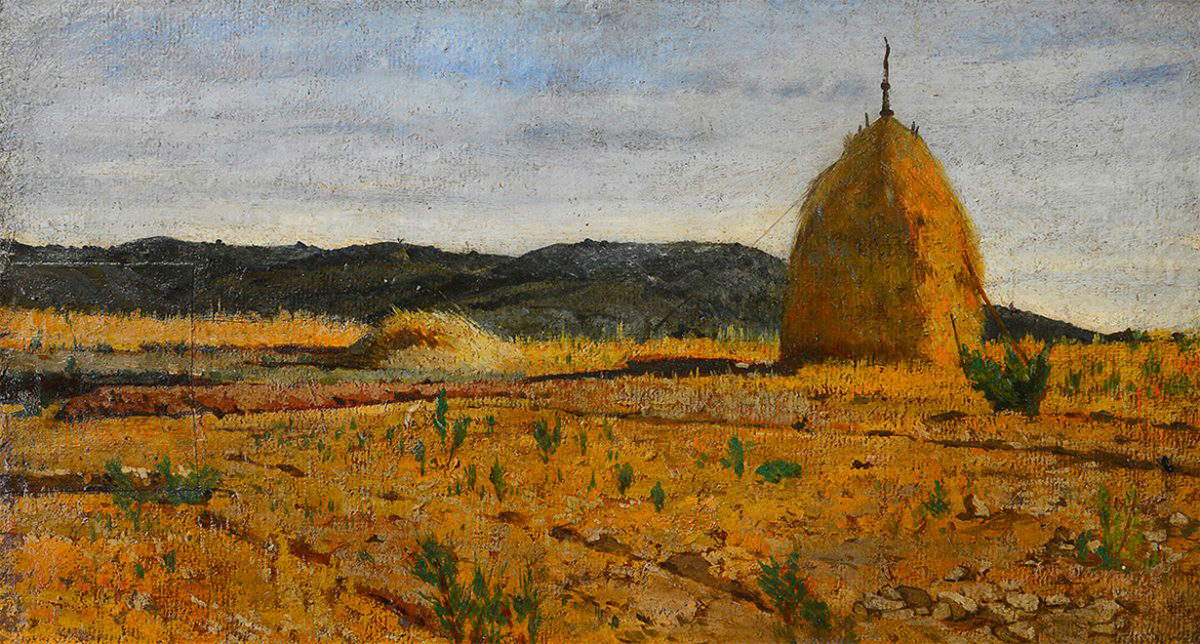

| Giovanni Fattori, Haystack (c. 1880; oil on cardboard, 24 x 42 cm; Livorno, Museo Civico Giovanni Fattori) |

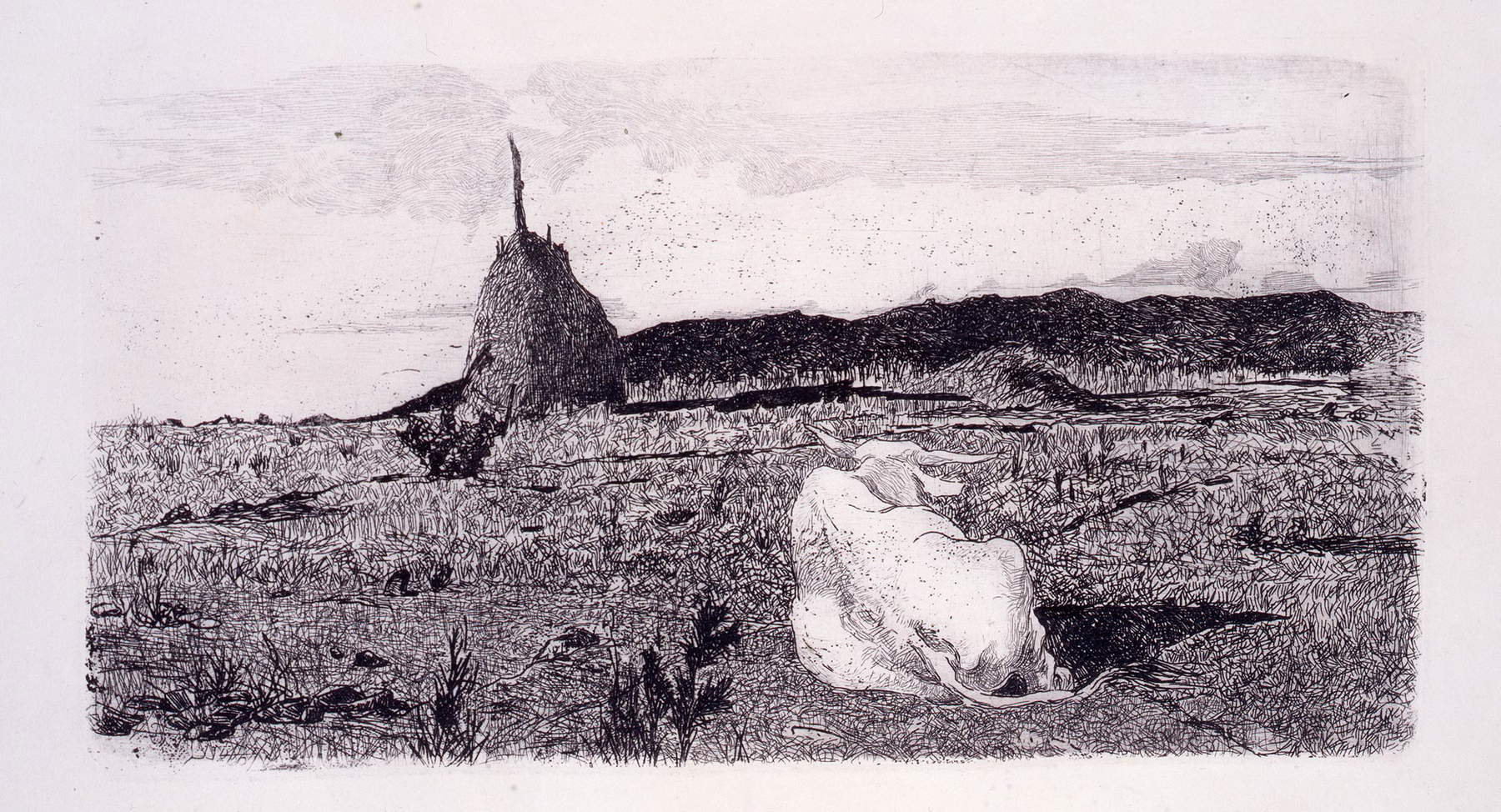

|

| Giovanni Fattori, Pio bove (early 20th century; etching on zinc). Reworks the landscape from the painting Haystack |

|

| Giovanni Fattori, On the Beach (c. 1893; oil on canvas, 69 x 100 cm; Livorno, Museo Civico Giovanni Fattori) |

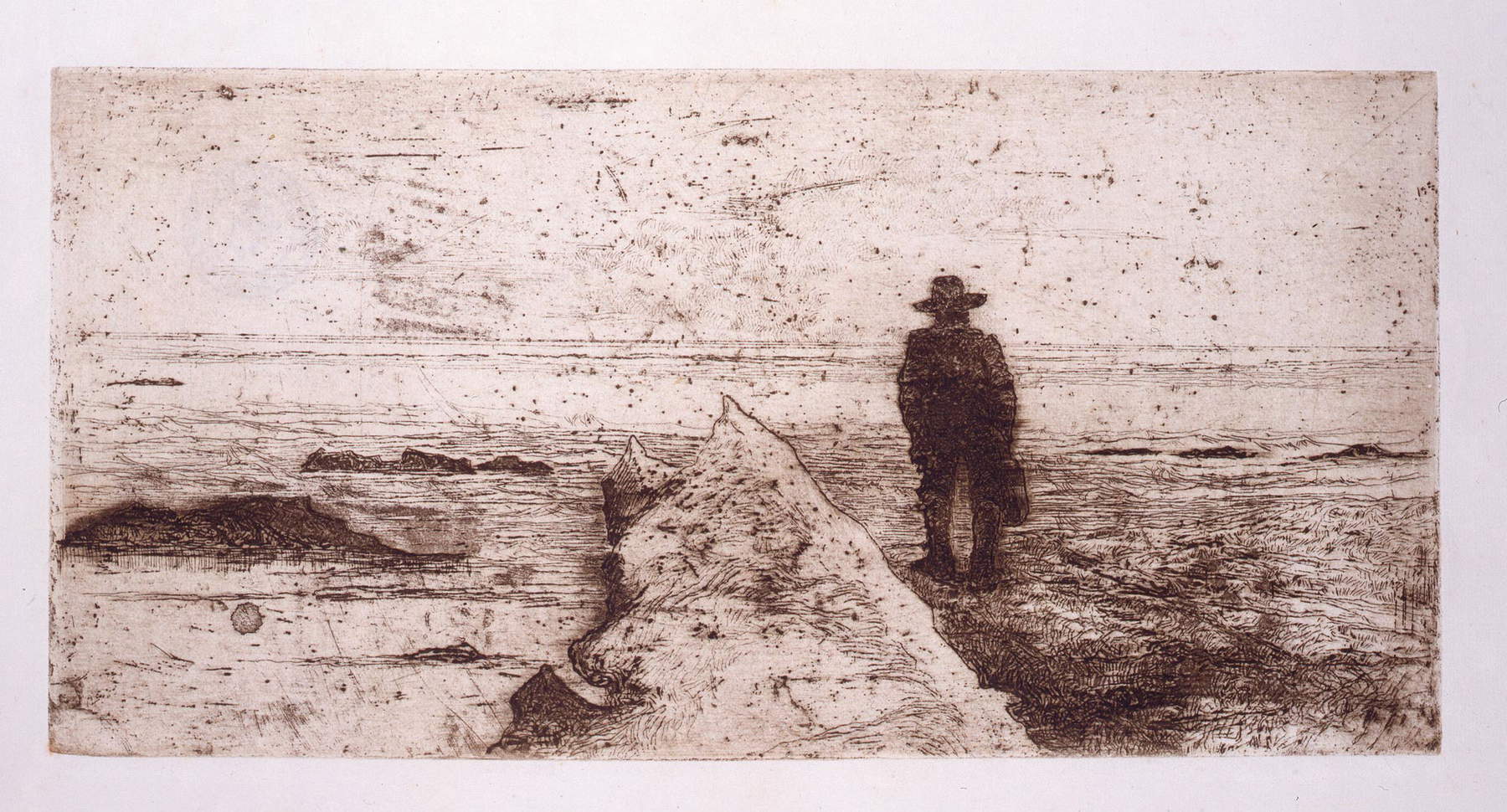

|

| Giovanni Fattori, On the Livorno Beach (early 20th century; etching on zinc). Reproduces the figure of the fisherman/mariner from the back of the painting On the Beach |

|

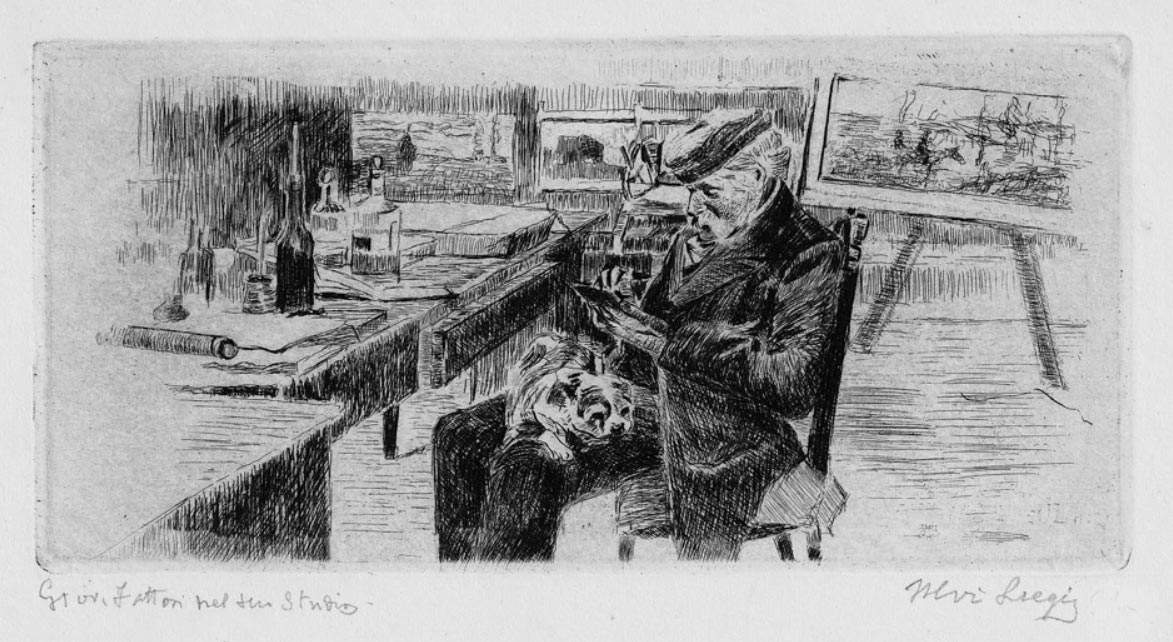

| Ulvi Liege, Giovanni Fattori while engraving (1902; etching) |

Through etchings, the Tuscan artist gave life to reinterpretations of earlier works, which, however, acquired new vitality in the graphic arrangement. This is the case of the print Donna del Gabbro, where the theme of the peasant woman from behind is reworked with a greater monumentality, not only mindful of the height of the Renaissance, but even anticipatory of certain volumetric solutions of the Novecento movement. Very different is the resolution of a work such as Peasant and Oxen where the thin, swarming texture neglects any plastic effect in the search for extreme formal rigor, while the complex latticework in Adua seems to want to emphasize the dramatic nature of the scene, with the animal in the center without a master, while in the lower left we see the wreckage of a battle, including a hand. In the sheet Swamp, he entrusts the wide white backgrounds with the secret of evoking the transparency of the waters, in a composition that also seems mindful of Japanese prints, while in Somarello al sole the white surface opens to a surprising solution, fulfilling the role of form and light. In The Return Home we find another typical Fattori piece, with the sunny little streets that engraver Lorenzo Bartolini called “the most beautiful drawn streets of all art of all time.” Other works seem genuinely anticipatory of later avant-garde research in the 20th century, such as Bovi, where the much cherished subject is almost abstracted, becoming an idealization of primordial forms, an absolute meaning, rendered through a brazen graphic synthesis mediated by brilliant formal intuition.

As the great critic Matteo Marangoni hoped, to date more than a “chapter has been written on Fattori’s etchings,” especially thanks to the efforts of Andrea Baboni, and perhaps the time is ripe to show again and make the general public appreciate this extraordinary production, among the highest of the 19th century and perhaps of the entire history of art.

The author of this article: Jacopo Suggi

Nato a Livorno nel 1989, dopo gli studi in storia dell'arte prima a Pisa e poi a Bologna ho avuto svariate esperienze in musei e mostre, dall'arte contemporanea alle grandi tele di Fattori, passando per le stampe giapponesi e toccando fossili e minerali, cercando sempre la maniera migliore di comunicare il nostro straordinario patrimonio. Cresciuto giornalisticamente dentro Finestre sull'Arte, nel 2025 ha vinto il Premio Margutta54 come miglior giornalista d'arte under 40 in Italia.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.