A recent book by Gabriele Bissolo, published in 2021 but updated in subsequent years in new editions, entitled Painters in Verona 1850-1920 (Edizioni d’Arte Quinta Parete), has collected the biographies of as many as 280 painters active in Verona between the late 19th andearly 20th centuries. At least since the Unification of Italy, Verona had become, after more than a century of marginality, a lively city of art following a significant event, the founding in 1858 of the Society of Fine Arts, which immediately s’activated to organize exhibitions capable of gradually attracting an increasing number of artists, especially after 1865, when the Society’s exhibitions were opened to artists from all over Italy. Initially, the few Veronese artists, given the historical ties, dating back to the Lombardo-Veneto era, with the Brera Academy and with Milanese exhibitions, continued to prefer Milan as an exhibition venue, but soon the situation would change, also helped by a turnaround of the local Academy of Fine Arts (theAccademia Cignaroli) with the arrival of up-to-date teachers who no longer made it necessary to travel too far out of town to learn about the main new developments. On the contrary, Verona also began to attract artists from outside the city: the foundations had thus been laid for the birth of an important local school, which would see in Angelo Dall’Oca Bianca (Verona, 1858 - 1942) its most illustrious and most attentive exponent.

Many of the Veronese painters developed a sensitive landscape painting that translated on canvas the deepest essence of a territory, that of the present province of Verona, with its gentle hills, picturesque valleys, the placid shores of Lake Garda and its own fascinating urban vistas, which lives on in the visual legacy of an artistic heritage that allows us to see and better appreciate the beauty of these places. From the most lyrical and contemplative expressions to the pinnacles of Futurism, Veronese painting of the last century has been able to recount an indissoluble bond between human beings and their land, offering valuable evidence of the changes and permanence of an era. The splendid landscape of the Verona area, from the plains to the mountains, from rivers to lakes, from villages to the city, was so varied that it offered painters an endless theory of suggestions, at a time when landscape painting was moreover at the center of artistic debate, with the development of the poetics of the landscape-state of mind that was fundamental in late 19th century Europe.

The journey could begin precisely with Angelo Dall’Oca Bianca, an indispensable figure for understanding the genesis of fin de siècle Veronese painting , not least because he himself was master and mentor to other artists, such as Erma Zago, Dante Bertini, Enrico Sorio and several others. Trained at the prestigious Accademia Cignaroli in Verona and then in Rome, where he came into contact with such illustrious figures as Carducci and D’Annunzio, and with the painter Francesco Paolo Michetti, who introduced him to photography, Dall’Oca Bianca developed a unique artistic language.

His most famous work in relation to the Veronese landscape, Prima luce, was first exhibited at the National Artistic Exhibition in Venice in the same year it was painted, 1887, and later at the Circolo Artistico in Trieste in 1890. Dall’Oca Bianca was not so much interested in landscape as he was in social denunciation: in fact, the work depicts the moment of the workers’ entry into the factory, although at the time critics focused mainly on the skill with which the painter was able to render the auroral light of this city glimpse overlooking the water. This ability to narrate social reality through landscape, without losing lyricism, made Dall’Oca Bianca a forerunner of a sensibility that had spread throughout Italy at the time. However, he was also a painter of landscapes of a more “traditional” character, we might say: famous and remarkable are his views of Verona, especially those of the mature phase of his career, which do not, however, reach the heights of the first phase of his career. Famous, for example, is his Piazza delle Erbe preserved, like many of his other paintings, at the “Achille Forti” Gallery of Modern Art in Verona, one of the most vivid depictions of the square located in the heart of the city.

Remaining in the context of Verona’s urban views, other artists who contributed to the city’s narrative also cannot be forgotten. Vittorio Avanzi (Verona, 1850 - Campofontana, 1913) was one of Verona’s most important landscape painters: one of his most interesting urban views, Verona’s Canal dell’Acqua Morta, is also at the GAM in Verona and is a symbol of his sober, calm and relaxed naturalism: he was not as innovative an artist as Angelo Dall’Oca Bianca, but his works, which also tell the story of the Veronese hillside landscape, especially that around Campofontana, the site of his long stays, demonstrate a perceptive sensibility in capturing the authenticity and beauty of Verona’s rural settings.

Another Veronese in love with his land, although from a later generation than Avanzi and Dall’Oca Bianca (and which was also the thickest generation), was Ulderico Marotto (San Michele Extra, 1890 - Verona, 1985), whose art, writes Bissolo, is “a revelation for the freshness of color, for the healthy and clean atmosphere that circulates in his paintings.” Although he initially worked as a decorator and graphic artist, his real passion was watercolor painting, particularly watercolor, a technique of which he became an acknowledged master. After years of wartime events, Marotto returned to Verona in 1942, where he opened his studio and began his career as a renowned watercolorist, devoting himself to numerous solo exhibitions. His interest in the Veronese landscape is central to his production: Marotto painted with lyricism “the scenes of the Veronese countryside, for the vanished or changed aspects of his city.” His works, such as Piazza delle Erbe of 1945, capture urban and rural views with a depth and spontaneity that stand out for their high degree of poetic interpretation of the city. From the same generation, Ettore Vitturi (Verona, 1897 - 1968), immortalized city views such as the 1933 Snowfall in Borgo Trento - Via Guerzoni. Similarly, Vittorino Bagattini (Verona, 1908 - 1983) painted Verona’s Piazza Erbe in 1941, offering a visual record of one of the city’s iconic places thirty-five years after Angelo Dall’Oca Bianca’s counterpart painting. These works, while focusing on urban architecture, are fully part of the narrative of the Verona “landscape,” understood in its broadest sense, that of an environment shaped by human beings and nature.

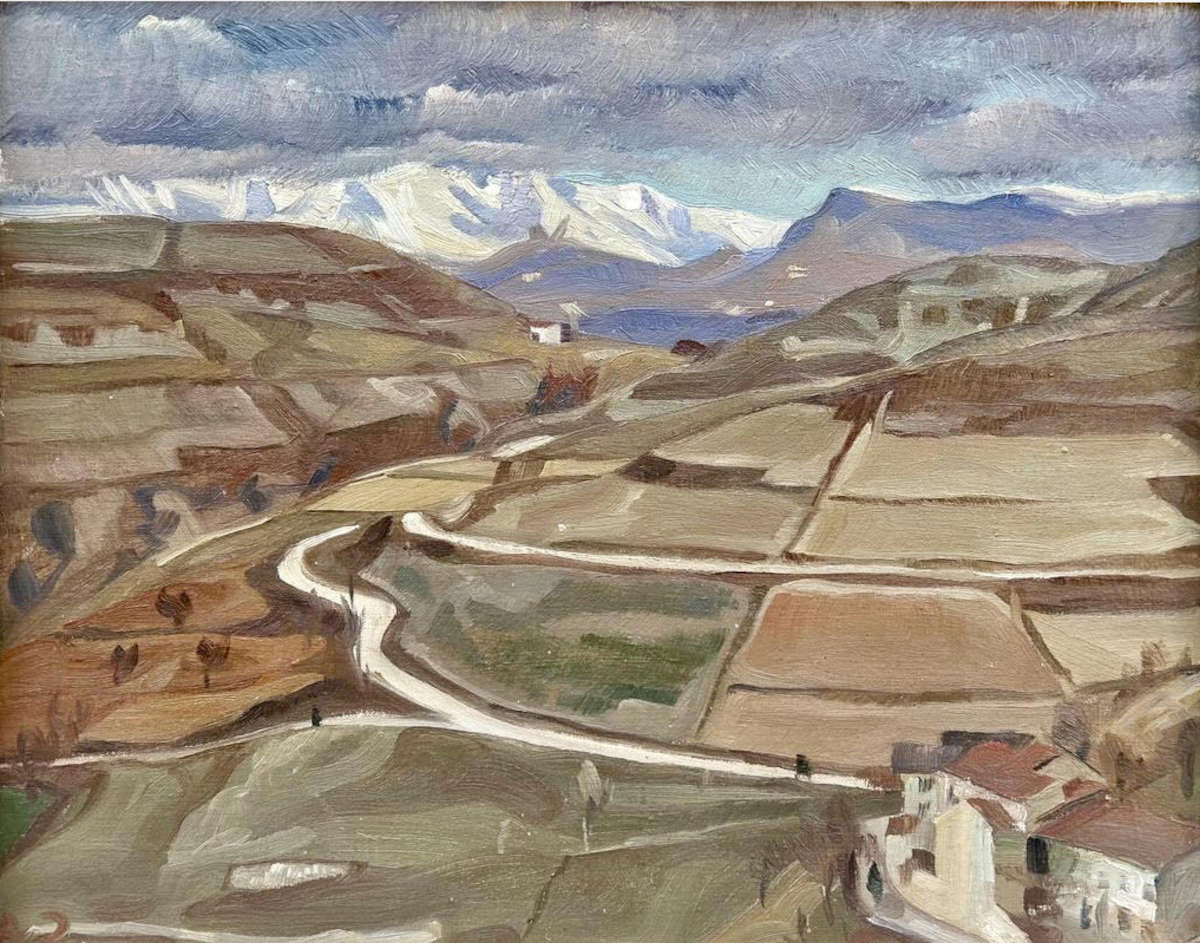

Another central figure in the twentieth-century Veronese art scene, belonging to the generation following that of Angelo Dall’Oca Bianca (which is also the thickest generation), is Guido Trentini (Verona, 1889 - 1975), whose artistic production is distinguished by its stylistic evolution and depth of interpretation. The son of painter Attilio Trentini, he began his training at the age of only thirteen at the Accademia Cignaroli. His career was marked by various influences, from Secessionism to traditional Veneto art, from the Novecento group to Cubism, demonstrating a remarkable openness and capacity for assimilation. In Verona, he was influenced by Felice Casorati, who had been active in the city since 1911, and was immersed in the lively climate of the Secession and the artists of Ca’ Pesaro, from whom he learned innovative anti-naturalistic solutions. His presence at the Venice Biennale was constant, with as many as fourteen participations, and in 1922 he won a prestigious first prize. After the death of his master Savini, Trentini took over as director of the Accademia Cignaroli, a period considered the peak of his career, characterized by a balance between formal rigor and expressive essentiality. Between 1910 and 1930 his art reached the highest levels of originality, before a period of research that led him toward Cubism in the 1940s. Of particular note in the context of Veronese landscapes is his work Colline veronesi (Valpolicella) from around 1915, an oil on cardboard that testifies to his interest in depicting the territory, in this case the famous Valpolicella hills. This work, while not his only work with a landscape theme, represents a direct point of contact with the heart of the Veronese countryside and its unaltered beauty transfigured according to the languages of the avant-garde.

Prominent figures who were able to interpret the Veronese and Garda landscape with particular intensity include Angelo Zamboni (Verona, 1895 - 1939), an artistic personality whose parabola, though brief, was one of extraordinary vivacity and influence. He too attended the Accademia Cignaroli, between 1910 and 1914, perfecting his mastery of fresco technique under Carlo Donati. From the very beginning, his artistic temperament did not go unnoticed; already at the age of twenty-two, in 1918, Massimo Gaglione described him as a “very ready, alert, continually fermenting wit,” part of a daring “Veronese coterie” that included names such as Lionello Fiumi and Eugenio Prati. His early creations reveal an early inclination toward new European artistic trends, such as the Vienna and Munich secessions, filtered through the innovative environment of Ca’ Pesaro and its protagonists, including Felice Casorati and Guido Trentini himself. From 1916 to 1925, Zamboni operated in his studio located between the Teatro Romano and Castel San Pietro, a place that became a point of reference for other Veronese artists of the time. His exhibition career was rich and significant, and for a time he was even considered a Futurist painter.

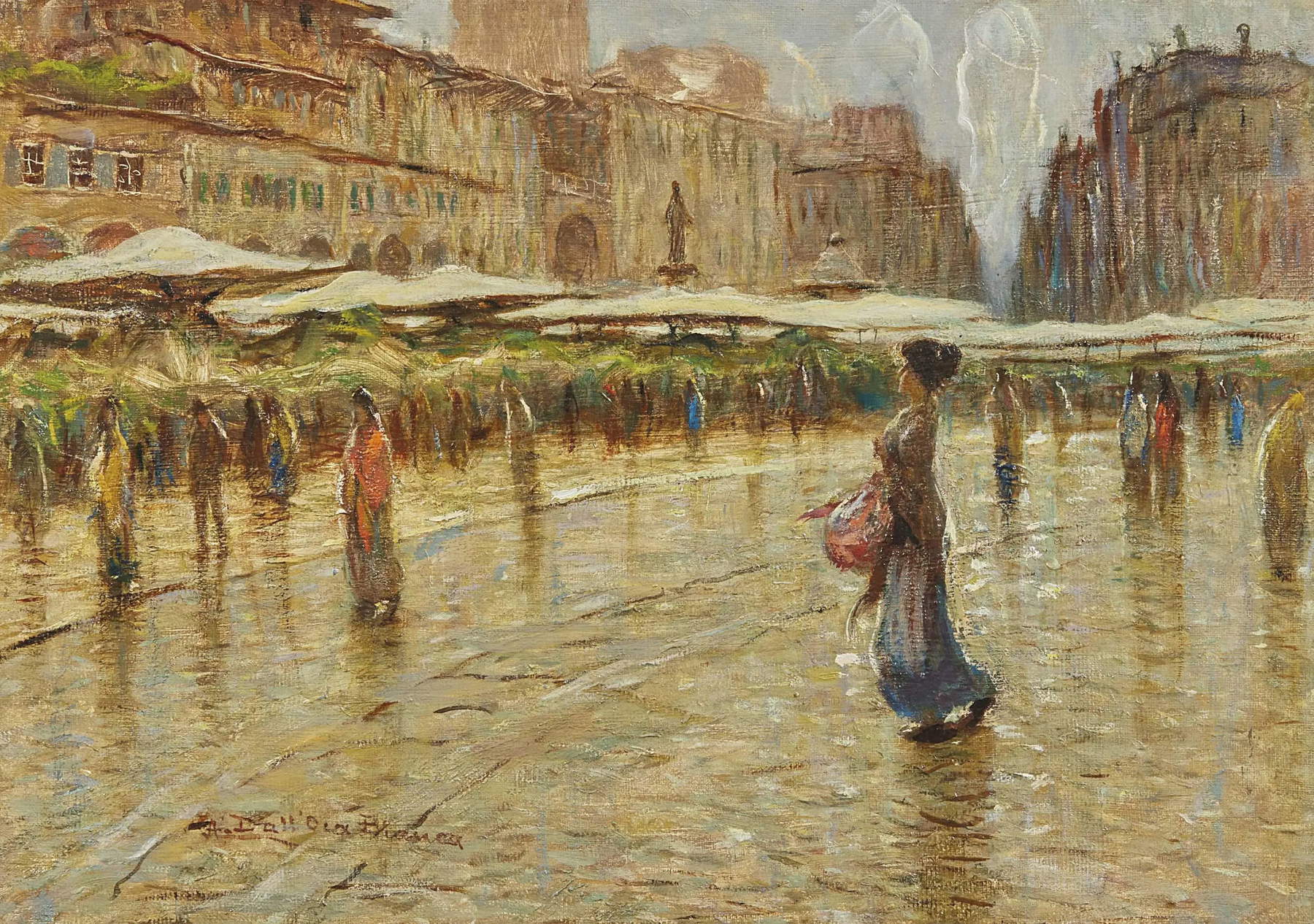

Above all, however, it is his deep connection with the Veronese land that emerges in his landscape production. A pivotal moment for his inspiration manifested itself in 1927, when he rented a family vacation residence in Romagnano, a charming location in the Valpantena valley. This small ancient village became for Zamboni an inexhaustible source of subjects and stimuli for the landscapes, especially those of the Lessini Mountains, which he would paint in the following years. His interpretation of the Romagnano landscape also culminated in an important fresco work of the presbyterial vault of the parish church in the summer of 1938. Critic Giuseppe Marchiori noted how Zamboni wanted to “express with simplicity his love for his Veronese land, in a serenely contemplative detachment.” Often, Marchiori wrote, “he achieved a rare freshness of vision. His imagination was populated with definite images.” The painter himself, in a 1931 letter sent to Marchiori himself, revealed an evolving creative freedom, stating that “control of the real no longer serves me, now one can abandon oneself to a more lyrical instinct, without falling into the danger of arbitrary symbolism.” Works such as Winter Morning (1922), Among the Olive Trees (1928) and Romagnano (1930s) testify to his sensitivity in capturing the atmosphere and light of these places. Despite his untimely death in 1939, at only 43 years of age, Angelo Zamboni left an indelible mark, with works exhibited posthumously at the Third Quadriennale d’Arte Nazionale in Rome and retrospectives dedicated to his memory, such as the one at the Museo di Castelvecchio in 1985.

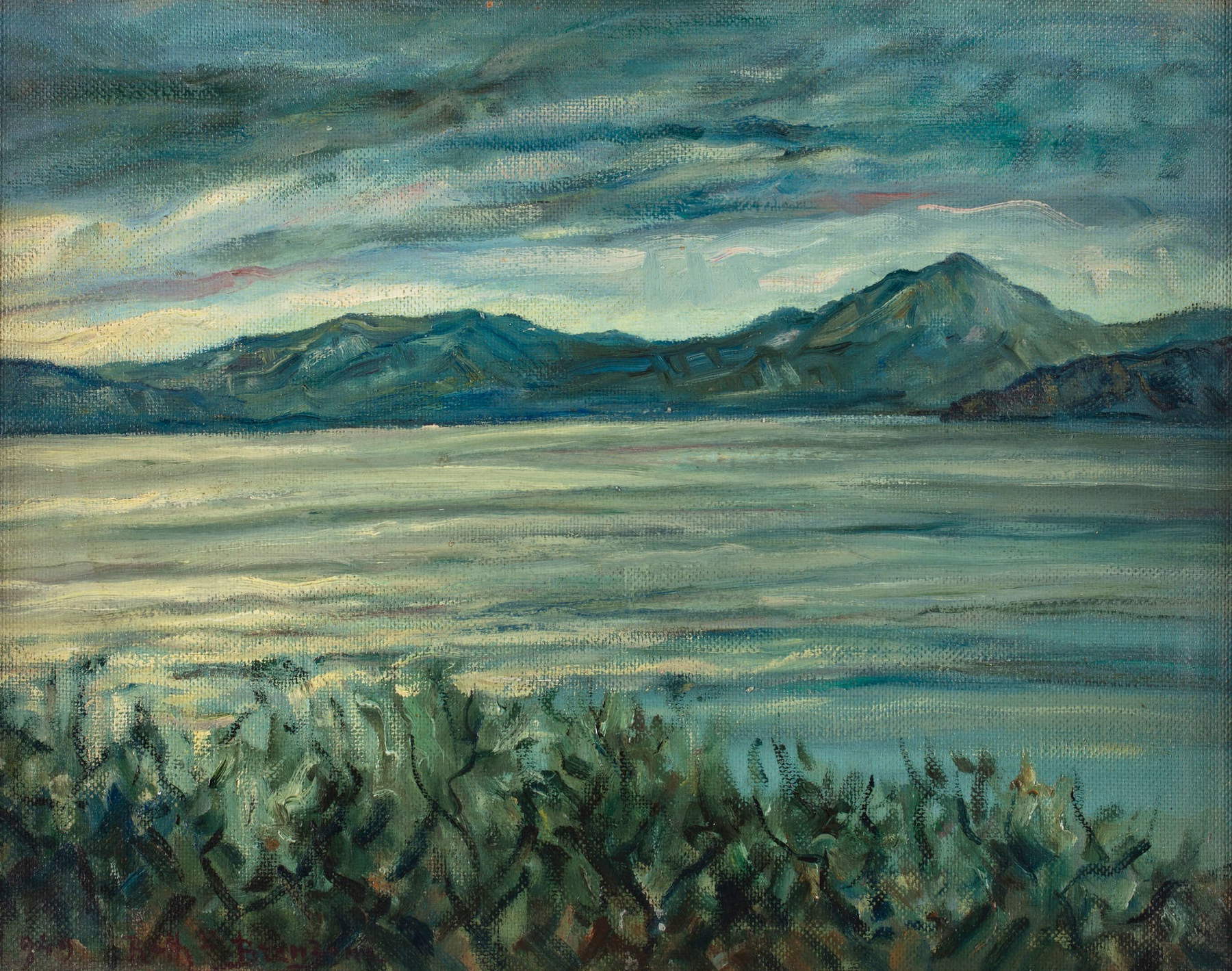

Lake Garda, with its changing lights and atmospheres, found in Alberto Stringa (Caprino Veronese, 1880 - 1931) a sensitive and original interpreter. Born and living in Caprino Veronese, Stringa, while earning a degree in law, devoted his life to art, music and poetry, following a passion that had accompanied him since childhood. He was not a student of any academy, except for the first rudiments he learned from the Veronese painter Francesco Danieli; his real master, he would always say, was “the real thing.” His exhibition career began in 1900 at the Society of Fine Arts in Verona and saw him present in numerous editions. Stringa traveled extensively, visiting Greece, Sicily, and staying in Rome and Paris between 1904 and 1905, where he came into contact with the artistic circles of the time and became acquainted with the works of the Impressionists, particularly Monet, to whom he was sometimes compared by critics. After his return from Paris, he spent a couple of years painting in Caprino Veronese itself, consolidating his connection with the local landscape. A significant period was his time in Vienna, from 1907 to 1913, during which he painted countless portraits and landscapes, exhibiting successfully and gaining recognition, while remaining faithful to his impressionistic-postimpressionistic coloristic taste, always in search of authentic expression. Despite his fame, Stringa later chose to retire to Caprino Veronese, isolating himself and devoting himself to his art far from the clamor of success, finding his happiness in the “small secret joys,” Bissolo writes, of his life and his land.

Another artist who has linked his name to the shores of Lake Garda is Raffaello Brenzoni (Verona, 1890 - Malcesine, 1971). Born in Verona and passed away in Malcesine, Brenzoni, although he came from an ancient noble family and had a background in law, devoted himself passionately to art. He was a noted art critic, author of more than 250 essays, and an accomplished restorer. Although his pictorial exhibitions were rare, his debut in 1918 at the “Mostra Pro Assistenza Civica” in Verona featured significant landscape works, all dedicated to Veronese views, such as Lights in the Evening, Malga in the Mountains, Sunset on the Burning Lessini and Forest in the Midday. These titles reveal a clear predilection for the landscapes of Lessinia and the Veronese mountain territory, captured with a sensitivity attentive to atmospheric and luministic variations. Brenzoni himself declared that he preferred landscapes not for the fleeting visual impression, but for the “feeling, the state of mind provoked by Nature.” After a 30-year hiatus, he resumed painting after World War II, and in 1949 exhibited Luci sul Garda da Brenzone, an oil on panel painting that captures the luminous atmosphere of the lake. His paintings, characterized by a twilight tone and light confined to the horizon, show a dense, enveloping painting style that is particularly effective in rendering Veronese landscapes.

Valpolicella, on the other hand, had a keen observer in Augusto Manzini (San Giovanni Lupatoto, 1885 - Verona, 1961). A native of San Giovanni Lupatoto, just outside Verona, Manzini trained at the Cignaroli Academy. His first exhibition at the Fine Arts Society of Verona in 1908 already revealed his ability to capture landscape atmospheres, with works such as Luci vespertine, praised for its light effects. His career led him to exhibit in important national contexts, from Ca’ Pesaro in Venice, where he was admitted with eight works in 1911, to Genoa, Milan and Rome. After a period in Brazil and trips to Sicily devoted to painting historical monuments and island landscapes, Manzini also returned to the landscapes of his homeland, as evidenced by the works San Giorgio di Val policella and San Giorgio di Valpolicella backlight, dated 1949, which show his ability to portray the beauty of Valpolicella. He died in Verona in 1961, destitute, but leaving a legacy of works that continue to celebrate the Veronese landscape.

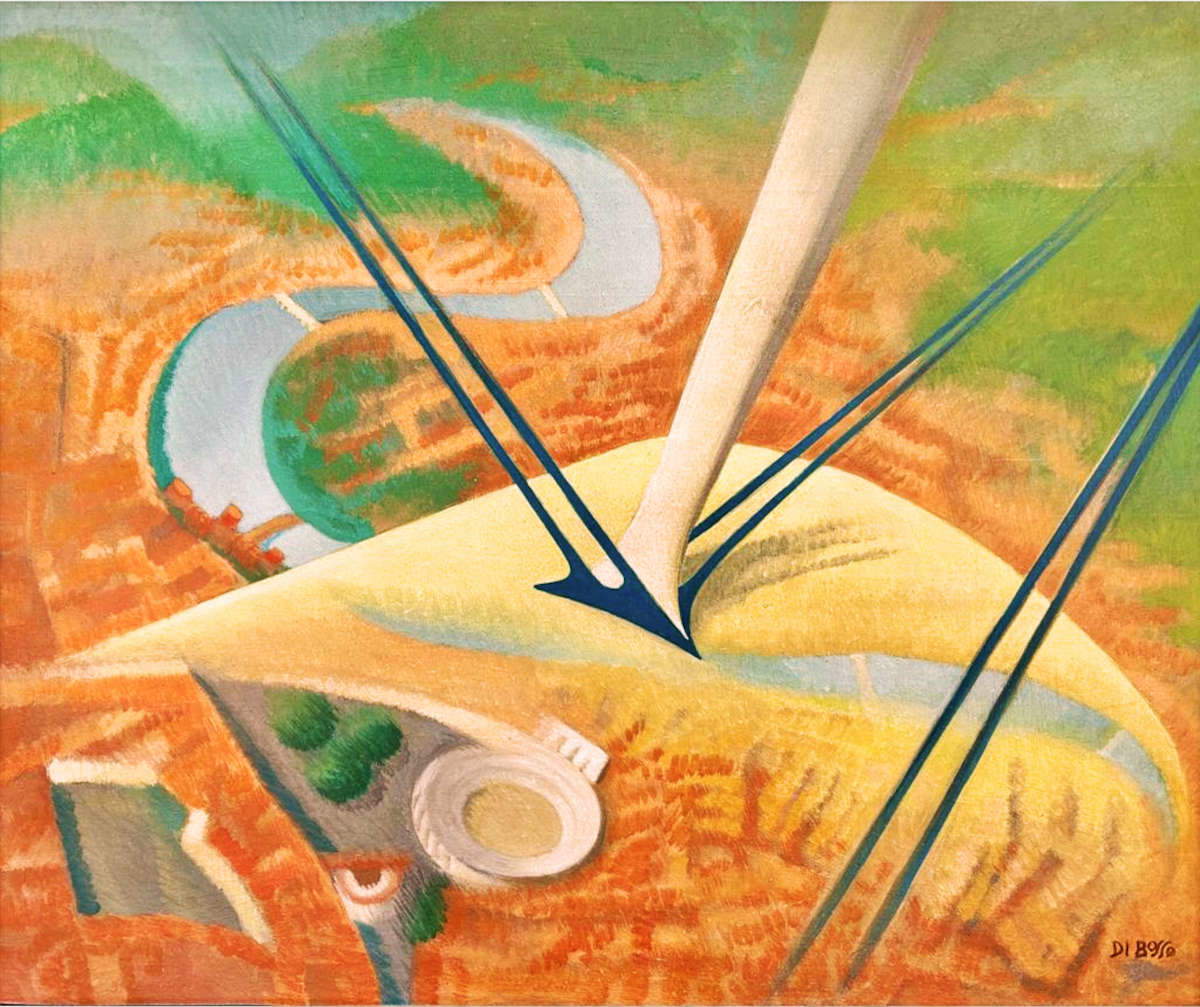

Mention should also be made of Renato Righetti - Di Bosso (Verona, 1905 - Negrar, 1982), an interpreter who was able to fuse his connection with the land with the avant-garde of the 20th century. Born in Verona and living in Arbizzano di Valpolicella, Righetti, a sculptor, painter and engraver, came from a family of sculptors. After studying at the Cignaroli Academy, he joined the Futurist movement around 1930, founding the “Veronese Futurist Group” and earning the nickname “Di Bosso” from Filippo Marinetti. His artistic research focused, from 1932, onaeropainting, which allowed him to represent the landscape from an unprecedented perspective, that of flight. He collaborated with his painter friend Alfredo Gauro Ambrosi at the Boscomantico airport, developing his unique and highly original “rotary tables”: movable circular supports that, by rotating on a central pivot, allowed the viewer to immerse himself in the sensation of flight and movement through the landscape. As described by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, these tables, although later losing motion to take on “shaped cloud-like forms,” continued to offer “zenithal visions” where the dynamic sense was given by the “suggestion of a firm and direct swoop on the lens.” This radically modern approach to landscape representation reflected the speed and new perspectives of the technological age. Although in a later period he also devoted himself to war painting, his focus on landscape resurfaced strongly from the 1960s onward.Righetti - Di Bosso did not cease to devote himself to his futurist ideas and produced at least twenty aeropictures dedicated to the Piazza delle Erbe in Verona. His work represents a bridge between figurative tradition and futurist innovation, and offers a dynamic and modern vision of the Verona landscape.

Finally, the work of Erma Zago (Ermanno Giovanni Zago; Bovolone, 1880 - Milan, 1942), the painter of rural landscapes of the Doges’ plain, deserves mention. The life and work of Erma Zago, often considered by critics to be a Macchiaioli painter, span the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century. He, too, was a product of the Cignaroli Academy, where he graduated in 1897. Crucial was his meeting with Dante Bertini and subsequent private lessons at the studio of Angelo Dall’Oca Bianca, the most famous Veronese painter of the time. Despite a move to Milan in 1901, where he established himself as a professional painter and portraitist, Zago maintained a deep connection with his homeland. His painting, characterized by a certain festivity and distinguished by its light effects, reflected a liveliness and attention to atmospheric rendering that could enrich any depiction of landscape. Many of his works also stemmed from photography , which he used extensively as a working tool. Zago, while not an exclusive landscape painter of the Veronese land, represents the example of an artist who, while opening up to national horizons, had kept his roots firmly in his native place, enriching his path with a broad and versatile vision of the representation of nature and the environments of his territory.

In general, the twentieth-century painters who have narrated the landscape of Verona and Lake Garda have therefore left a profound and multifaceted imprint. From the introspective lyricism of Angelo Zamboni and Alberto Stringa, to the technical mastery of Guido Trentini, passing through the contemplation of Raffaello Brenzoni and the urban visions of Ulderico Marotto, to the futurist innovation of Renato Righetti Di Bosso and the interpretations of Augusto Manzini, these artists were able to capture the soul of an area, translating it into works that still resonate with the beauty, history and emotion of the places. Their art is not just a visual documentation, but a profound exploration of the link between man, culture and landscape, an invitation to rediscover, with new eyes, the wonders of Verona and Lake Garda.

This journey through the brushstrokes of the 20th-century Veronese masters reveals not only the intrinsic beauty of the area, but also the ability of art to preserve its memory, documenting transformations and perpetuating an unbreakable bond between man, his culture and the surrounding environment. The landscapes of Verona and Lake Garda continue to live and shine through the legacy of these artists, inviting anyone to perceive the territory not only as a physical place, but as an inexhaustible source of inspiration and beauty.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.