One of the most important works in the history of Western art, the earliest example of Christus Triumphans of which we have any knowledge (at least according to the date that appears on the epigraph, which sets 1138 as the date of its creation), a painted cross fundamental to the development of art in Tuscany and its environs, is found in the cathedral of a Ligurian town of just over twenty thousand inhabitants: it is the celebrated Cross of Guglielmo, preserved in the Co-cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta in Sarzana. Its image shows itself in all medieval art history books, it is the subject of study in almost every school where art history is taught, and we can consider it one of the fundamental icons of our art. It is therefore worth delving into its history and trying to discover its most significant details.

|

| Guillielmus (William), Christus Triumphans (1138; tempera on panel, 299 x 214 cm; Sarzana, Cathedral) |

|

| Guillielmus’ cross in its location |

|

| The Cathedral of Sarzana |

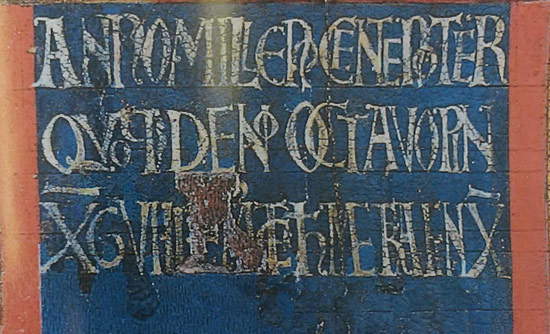

We can begin with the author’s name, which, together with the date 1138, appears in the inscription we see immediately below the titulus crucis, that is, the cartouche bearing the reason for the condemnation that was customary to affix to crosses, and which in the case of Jesus also took on cynically sarcastic tones: we see this clearly in the Sarzana Cross, because the author has written the titulus in full(Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudeorum, or “Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews”). Although the epigraph attests that it was made by an unspecified “William” (here is the text: Anno milleno centeno ter quoque deno octavo pinxit Guillielmus et hec metra finxit, i.e., “in 1138 William painted the work and wrote these verses,” i.e., those in the epigraph but also those in the panels below with the Passion stories, which have, however, become almost completely illegible), we actually have no other documents concerning the author, no information about him, and obviously this is the only certain work of his that we know of. By virtue of the fact that this Guglielmo (or “mastro Guglielmo,” as he often happens to be named) knew Latin to the point of composing the inscription and captions in hexameter, and at the same time had a good familiarity with the paintbrush, and since a number of miniatures have been attributed to him (on a stylistic basis), art historian Marco Ciatti in a recent study contained in the volume La pittura su tavola del secolo XII, has judged likely the possibility that the author of the Sarzana Cross was “a religious industrious in a kind of monastic workshop particularly active in that period, both in the field of paintings on wooden support, and probably, in miniatures.” Let us not forget that a thorough knowledge of Latin to the point of writing verse belonged, at that time, to very few people, coming almost exclusively from ecclesiastical circles.

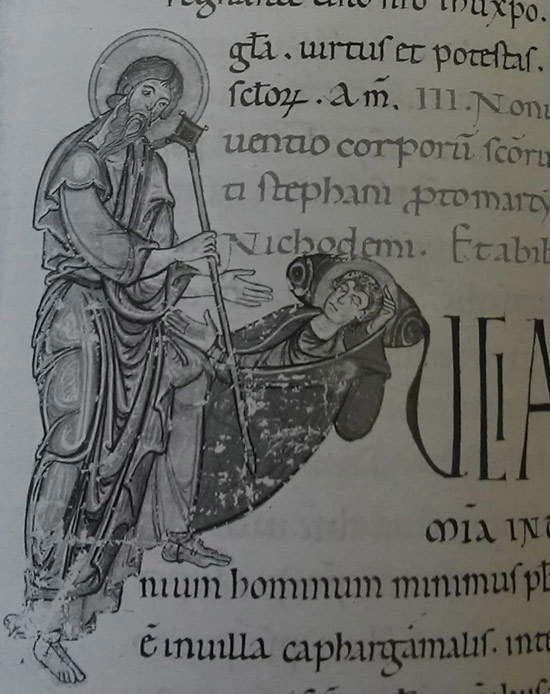

Critics have long established that our Guglielmo must have been an author from the Lucca area. Not only because there is in Lucca a large group of later painted crosses (such as the one in San Michele in Foro or the one preserved in the National Museum of Villa Guinigi, originally at the church of Santa Maria dei Servi) that share forms and style with the one in Sarzana, but also because as early as 1953 the American scholar Edward Garrison had related Guglielmo’s Cross to the so-called Passionary P+ in the Capitular Library of Lucca: this is a manuscript containing the Gospel passages narrating the Passion of Jesus, which shares several stylistic solutions with the Cross (the connotations of the face, such as the shape of the eyes, mouths and noses, the way the characters’ robes are depicted, the chromatics). Interesting, for example, is the comparison between a telamon that appears in the Passionary, and the figure of the right-hand henchman in the Flagellation scene that appears next to the legs of Jesus in the Sarzanian Cross: the charged faces of the two characters appear quite similar.

|

| The inscription |

|

| Appearance in a dream of Gamaliel to Lucian, from Passionary P+, c. 36r (Lucca, Biblioteca Capitolare) |

|

| Comparison between the Flagellation on the Cross and the telamon from the Passionarium P+ |

The Sarzana Cross has long been thought to be the first painted cross in history. While it is true that it is the first of which we know the date, it should nevertheless be emphasized in the meantime that it cannot be the first work on wood panel produced in Italy (since, as the scholar Ciro Castelli also pointed out in the above-mentioned book, “the manner in which it is made shows that the craft tradition behind it is, at the time of its making, more than attested and stabilized”), and then that there have been art historians inclined to identify in other painted crosses, the dating of which we do not know for sure, earlier experiences than Guglielmo’s work. This is the case, for example, with Miklós Boskovits, one of the greatest scholars of medieval art in recent years, according to whom a work such as the Rosano Cross (a painted cross found in the monastery of the locality near Fiesole and also dating from the 12th century) could be older than the Sarzana cross because of the fact that, although we are talking about two distinct geographical areas (Florentine area and Lucca area), our Guglielmo would seem to be a more evolved artist than the one who produced the Florentine area cross. For Boskovits, some of the details of the Passion stories that we find in the panels next to the legs of Jesus (such as the way the characters arrange themselves around Christ in the panel with the Kiss of Judas and the greater realism in the Deposition scene) would be indicative that the Sarzana Cross may have been produced with greater awareness, due to an increased demand for works of this type.

|

| The scene with the Kiss of Judas (image from the Sarzana Cathedral website) |

|

| The Cimasa of the Cross of William |

|

| The hands of Christ with the figures of the prophets |

|

| The figures of the mourners |

As for the figure of Christ, the recent restoration, conducted between 1991 and 1998 by theOpificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence, confirmed that it is a complete repainting dating from a period that the latest hypotheses place fifty years after the date of 1138 attested by the epigraph. Since, therefore, it is such an ancient repainting, the restorers deemed it appropriate to avoid removal, although the result of this decision consists in a perception of the work that is different from the one that could be had before the Cross as soon as it left the workshop in which it was made. The scholar Anna Rosa Calderoli Masetti, in one of the last contributions on the Cross, has given an account of how the figure of Jesus must have looked originally: "it is possible to recompose, albeit in broad outlines, at least the original situation of the face, through an X-ray that gives us back a more pronounced frontality of the head, the terribleness of the large wide-open eyes, the ’camused’ structure of the nose, very similar to that of the Dolenti, which were not touched in the later intervention. The body, on the other hand, would not present, in the forms in which we see it now, great differences from how it was originally. Still Marco Ciatti, on the basis of such evidence, believes that the repainting had become necessary not so much for reasons of iconographic modernization, but to “repair some small faults suffered.” However, an update conducted on the basis of an execution “more sensitive to chromatic subtleties and plastic softnesses” would have been sufficient, according to scholar Antonino Caleca, “to make the figure of Christ closer to the humanity of the Christian faithful.” The recent restoration that led to all these reflections is but the latest chapter in a story spanning nine centuries: it is worth retracing its main stages.

The most recent reconstruction of the documentary history of the Cross of William is the merit of Piero Donati, who dates the first secure document concerning the work to 1602. It dates to June 25 of that year an agreement between the Chapter of Sarzana Cathedral and the Cattani family, one of the most prominent in the Ligurian town: this agreement provided for the Cross to be transferred from what was then its location, the wall above the door of the sacristy of Santa Maria, to the Cattani’s chapel, who were moreover allowed to adorn the chapel, dedicated to St. John the Baptist, with paintings. The document reports that the terms of the agreement were agreed upon with the then bishop of Luni and Sarzana, the Genoese Giovanni Battista Salvago, who headed the diocese for a full forty-two years, from 1590 to 1632. The information is interesting because, after the Cross was transferred to the chapel of St. John the Baptist, the work became the object of heartfelt popular devotion, so much so that the bishop was prompted to issue rules to regulate the flow of offerings left in the cathedral: among the administrators appointed by the bishop to deal with the economic management of the alms was Canon Ippolito Landinelli (1568 - 1629), a learned scholar of local history. In one of his treatises, Dell’origine della città di Luni e di Sarzana, Landinelli reported the rumor that the Cross was originally in the ancient city of Luni and was brought to Sarzana later. The historian also attests that in Sarzana the work first found hospitality in the church of Sant’Andrea, and then, after a period in which it was forgotten, it found a worthy location in the Cathedral, above the door of the sacristy, that is, in the exact spot where documents attest its presence in 1602. However, Landinelli did not show much conviction of the hypothesis of a Lunense provenance (“whether said miraculous crucifix came out of Luni, or is proper to Sarzana, [it was] apeso per cintinaia d’anni a una longa trave, che divideva il Choro dell’antica Parochia nostra di Santo Andrea”). And in fact, more recent criticism (beginning with Donati himself) considers it more plausible that the work was made precisely for Sarzana, and not for Luni, a city whose cathedral was in 1138 “in full decay,” as Donati points out, while in Sarzana the church of St. Andrew had recently been built, which, as one might expect, was to be suitably adorned with a beautiful crucifix.

In 1712, the titularity of the chapel of St. John the Baptist was transferred to the powerful Sarzana cardinal Lorenzo Casoni (the Cattani family obtained in exchange the juspatronage of the third chapel in the left aisle): the latter, the following year, initiated renovations that gave the chapel its present appearance. Cardinal Casoni, moreover, commissioned one of the most prominent painters of the time, Francesco Solimena (Serino, 1657 Naples, 1747), known in Naples, the city where the prelate had been apostolic nuncio from 1690 to 1702, to paint a canvas “to which was entrusted the task of protecting, by way of a shrine, the Cross of Guglielmo.” in the painting, Pope Saint Clement, who appears along with Saints Philip Neri and Lawrence, points to the oval carried by angels, inside which onlookers could observe the face of William’s Christ (the rest of the cross was concealed by the painting). The separation of the canvas from the Cross, Donati continues, was implemented in the 1940s, a time to which the first restoration of the canvas also dates, which preceded the one, mentioned above, conducted by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure: this is the last chapter in the history of the Cross, one of the most important works in our art history.

Reference bibliography

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.