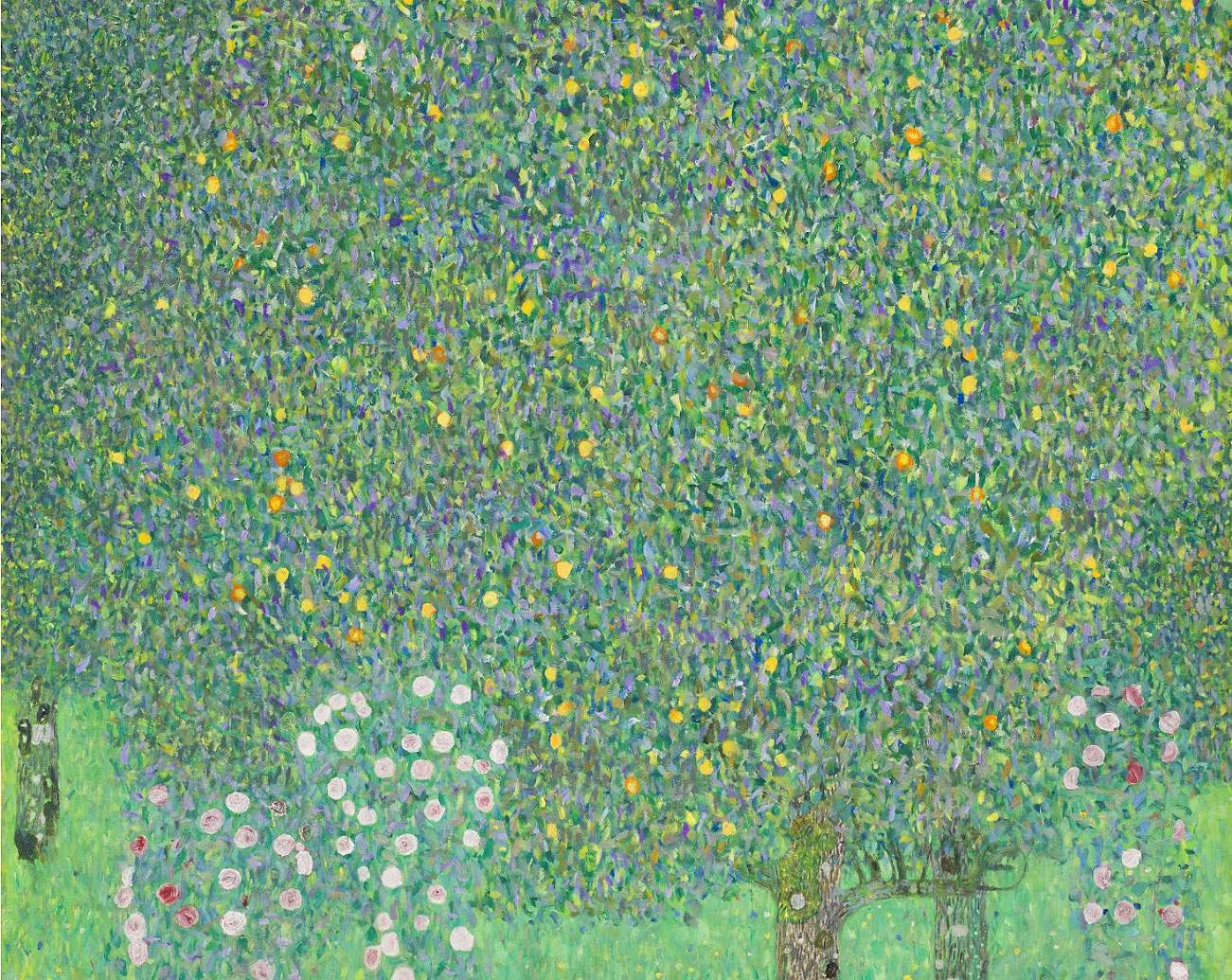

For several years, the only work by Gustav Klimt (Vienna, 1862 - 1918) in French public collections was a painting entitled Roses under the Trees, which the great Austrian artist painted around 1905, bringing his passion for the beautiful spring flower to the canvas. Roses under the Trees is a painting that tells at least two stories: the first is that of its troubled historical vicissitudes, and the second is that of Klimt’s love for roses. It is a work that rose to international headlines in 2021: in March, in fact, the French government decided to return the painting, which was on display at the Musée d’Orsay to its rightful owners, the heirs of Austrian collector Nora Stiasny, who in turn had inherited the painting from collectors Viktor and Paula Zuckerkandl. The Roses under the Trees had been taken from her by the Nazis in August 1938, following the Anschluss (i.e., the annexation of Austria to Germany) with a typical modus operandi: Jews were charged extremely exorbitant taxes, and those who could not pay them had to surrender their property. This was how the Nazis took possession of a huge amount of artwork. Stiasny lost her life in the death camps in 1942, along with her mother, husband and son: in 2001 the family made a formal request for its return, and finally in 2021, thanks to an action by the Musée d’Orsay, the French Ministry of Culture, Galerie Belvedere in Vienna and the legal representatives of Nora Stiasny’s heirs, it was possible to return to the family the painting, which the French state had purchased on the market in 1980.

Klimt had painted his Roses under the Trees during one of his summer stays in Litzlberg, a verdant resort town on the Attersee, a lake not far from Salzburg: the artist takes the relative to a lush orchard (so much so that for some time the work was also catalogued as The Apple Tree), where we find a number of apple trees occupying, with their fruit-laden foliage, almost the entire composition, and in the lower register a candid rose garden with three shrubs of what appears to be a centifolia rose, a species particularly in vogue in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As is often the case even in paintings in which Klimt brings nothing but plants and flowers to the canvas, the idea is to evoke the appearance of a mosaic whose tiles are the leaves, flowers, fruits, and blades of grass. On the occasion of its return in 2021, the work was described by the French Ministry of Culture as “one of Klimt’s most spectacular” because of the way the artist treats the subject, that is, without modeling or perspective: the essences become almost pure decoration, approaching abstract art. Klimt’s decorativism has its roots in Neo-Impressionism (from which he takes the idea of distributing color on the canvas through simple juxtaposed brush strokes) but also in Byzantine mosaics: in 1903, the Secession artist had made a trip to Ravenna and was fascinated by the masterpieces he had been able to observe in the city.

|

| Gustav Klimt, Roses under the Trees (c. 1905; oil on canvas, 110 x 110 cm; Private collection, formerly Paris, Musée d’Orsay). Photo by Patrice Schmidt |

|

| Gustav Klimt, The Rose Garden (1911; oil on canvas, 110 x 110 cm; Austria, Private Collection). Photo Klimt Villa |

It is the triumph ofViennese aesthetics: the colors of the leaves meet and clash with the muted hues of the roses and the yellows of the apples to make all the elements of the landscape dissolve (we distinguish nothing but the trunks of the trees and a small patch of sky), in a composition that does not allow for emptiness and that establishes the priority of ornament over everything else. This is not, however, the only painting by Klimt with roses as its theme: there is one, preserved in a private collection, that is probably even more fascinating than the one in the Musée d’Orsay, due to the fact that it is much more intimate and tells some interesting aspects of the artist’s life. Known as The Rose Garden(Der Rosengarten), the painting was executed by Klimt in 1912: the artist was inspired by the blooms in his garden at Feldmühlgasse in Vienna’s suburban Unter Sankt Veit district of Hietzing. It is one of the most beautiful areas of Vienna, within walking distance of Schönbrunn and the Roter Berg, among parks and long tree-lined boulevards.

The artist had moved here after leaving his historic studio at Josefstädter Strasse 21, in the 8th district (it was where he had painted the Kiss): in fact, he had found a small villa in Feldmühlgasse, which had been rented to him by a furniture maker, Joseph Herrmann, known in art circles as his daughter had married the painter Felix Albrecht Harta, and it is likely that through the latter Klimt learned of the possibility of renting the house. He would live there until his disappearance, which occurred in February 1918. Today, Klimt’s villa is a visitable museum, called just Villa Klimt, although the appearance of the building is not exactly the same as the one the painter had known. After the artist’s death, in fact, the Hermann family expanded the building with a major renovation, which was continued in 1923 by the new owners, the Klein family, who added a floor, a porch and an exterior staircase to the structure. The rooms in which Klimt worked, however, were not altered, and can be visited today. The villa also did not have an easy life during the Nazis: the Klein family, who were Jewish, had to leave Austria, and the villa was seized by the Nazis, although the rightful owners in this case did not have to wait long to regain possession, as the house was returned to them soon after liberation in 1945. However, the Klein family had permanently moved elsewhere, so in 1957 they resolved to sell the house to the Austrian state.

|

| Klimt Villa. Photo Klimt Villa |

|

| Klimt Villa. Photo Klimt Villa |

|

| Klimt’s villa. Photo Klimt Villa |

|

| The reconstruction of Gustav Klimt’s studio. Photo Klimt Villa |

Initially, the state used the building first as a school and then as a warehouse, after which the villa went into a long period of neglect and was even in danger of being demolished. Fortunately, on the occasion of the “Year of Klimt” (2012, the 150th anniversary of his birth), Austrian authorities decided to breathe new life into the building, realizing to proceed with a complete restoration of the Villa, reconstructing in detail Klimt’s studio and the room where he received guests. Managed by a private foundation, the Verein Gedenkstätte Gustav Klimt (the Gustav Klimt Memorial Society), Villa Klimt was awarded theEuropean Heritage Award (the recognition, given annually by Europa Nostra, that stands as the most prestigious European award in the field of conservation and preservation) in 2014: “the Klimt Memorial Society,” the citation reads, “led a fourteen-year campaign to convince the Austrian government to preserve Villa Klimt and its garden as a public space to be open to all. Society volunteers conducted guided tours and organized cultural events, and now, with Federal Monument status, Klimt’s last studio has been faithfully reconstructed inside the fully restored villa so that it can become a unique piece of European cultural heritage.”

The garden, as mentioned, is also an integral part of the villa. The outdoor space and rooms in which Klimt worked have been preserved because in 1918, after the artist’s death, his friend Egon Schiele (Tulln an der Donau, 1890 - Vienna, 1918), who used to frequent Klimt’s atelier, asked the owners not to alter the spaces in which the artist had worked. We know about his relationship with Klimt through his memoirs, collected by critic Arthur Roessler in a book published in 1948. “Nothing should be removed, because everything connected with Klimt’s house is one and the same and is a work of art in itself, which must not be destroyed,” Schiele said about the villa a few days after his friend’s death. “The unfinished paintings, the brushes, his work table, his palette should not be touched and the studio should be opened as a Klimt Museum for all those who appreciate and love art.” It is good to see how, almost 100 years later, Schiele’s wish has been granted.

And Schiele himself is one of the main witnesses to Klimt’s passion for roses. Roessler, in his book, published a memoir in which the young artist describes a visit to Klimt’s villa: the painter, Schiele recalled, “decorated the garden around the house in Feldmühlgasse with flower beds every year. It was a pleasure to visit it and to find oneself among old flowers and trees. In front of the door were two charming heads that Klimt had carved. One first entered an antechamber with a door on the left that led to his reception room. In the middle was a square table, and all around it were grouped Japanese prints and two large Chinese paintings. On the floor were African sculptures, and in the corner where the window was a red and black Japanese armor. This room led to two other rooms from where you could see the rose garden [...]. Klimt showed me the paintings he was working on. In Hietzing he had painted a series of female portraits and figure paintings [...]. In addition, he painted several landscapes of the Attersee and Lake Garda, which were not yet known in Vienna. And again, in Feldmühlgasse there were thousands of his drawings, and in exhibitions one always saw the odd one.... ”. The roses that can be seen in the picture from a private collection of 1912 are Damask roses(rosa damascena), which had been planted in the garden of the villa already around 1900. And which were replanted after the villa was turned into a museum. But the shrub known as the “Klimt rose” is still preserved: it is the rose bush planted in the artist’s time, which was reinvigorated and enlarged during restoration work.

|

| Gustav Klimt, Tree of Life, detail (1910-1911; paper, colored pencil, gold, pastel, platinum, silver and bronze on cardboard, 200 x 102 cm; Vienna, Museum für angewandte Kunst) |

|

| Gustav Klimt, Kuss der ganzen Welt, detail of Beethovenfries (1902; casein on stucco; Vienna, Secession Palace) |

|

| Gustav Klimt, Kuss der ganzen Welt, detail of Beethovenfries (1902; casein on stucco; Vienna, Secession Palace) |

The paintings mentioned above are not the only ones by Klimt in which roses appear: the spring flower is a fairly recurring symbol in Klimt’s painting. A rose bush appears, for example, in theTree of Life of the Stoclet Frieze, preserved at the Museum für angewandte Kunst in Vienna. Again, roses provide the backdrop for Beethovenfries ’ Kuss der ganzen Welt (the “Kiss to the Whole World”) preserved today at the Secession Palace in the Austrian capital: the scene takes place in a lush rose garden. Roses then appear, along with other flowers, in several portraits (for example, the third portrait of Ria Munk, begun in 1917 and unfinished, now preserved at the Lentos Kunstmuseum in Linz: it is one of the largest portraits from the last stages of the Viennese artist’s career).

Roses, in Klimt’s art, obviously refer to their universal meaning, as a symbol of love and passion. And when Klimt exhibited his Roses under the Trees at the Kunstschau in Vienna in 1908, the poet Peter Altenberg (Vienna, 1859 - 1919) had also seen Klimt’s flowers as a symbol of sensuality, as an allegory of the fullness of life, and wrote a comment addressing the very same artist: “Are you a true, honest friend of nature? Then drink these paintings with your own eyes: the garden of the house, the beech forest, the roses, the sunflowers, the poppies in bloom. You treat the landscape as you would treat a woman: you raise it up to its most romantic spires, do it justice, transfigure it, and make it visible to the gloomy, joyless eyes of the skeptics! Gustav Klimt, you are a strange mixture of primitive force and historical romanticism, may the Prize be yours!” So this is what roses, and flowers in general, were to Klimt: they were also joie de vivre.

For more information about Klimt’s Villa and its garden, you can visit the official website austria.info.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.