Are you familiar with Hokusai’s The Great Wave? In this article written by Paola Vázquez and published on the Mexican blog Cultura Colectiva, this very famous work is explored in depth by resorting to Zen philosophy. If you are curious, read the article in Ilaria’s translation. Here is the link to the original;)

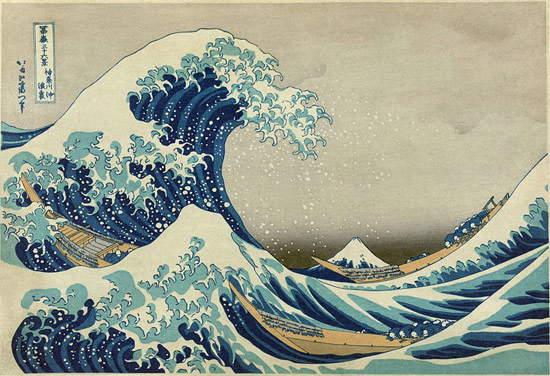

What do these images reveal about a rough sea that threatens to sweep us away in its frothy billows? The print of The Great Wave of Kanagawa is a demonstration of the simplicity of Japanese aesthetics and a philosophy related to Zen Buddhism. When we look at the works of the floating world of Katsushika Hokusai (Edo, 1760 1849), it is inevitable that, without knowing their origin, we detect an Eastern aesthetic that draws us into direct contact with nature. Hokusai envelops us with his gaze; he is the man who drew everything from larvae to the sun, as José Juan Tablada, the first popularizer of Hokusai’s work in Mexico, would say.

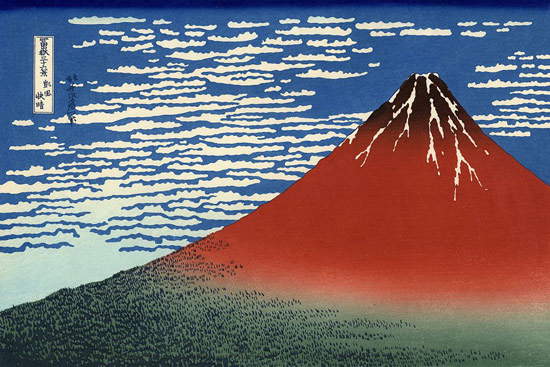

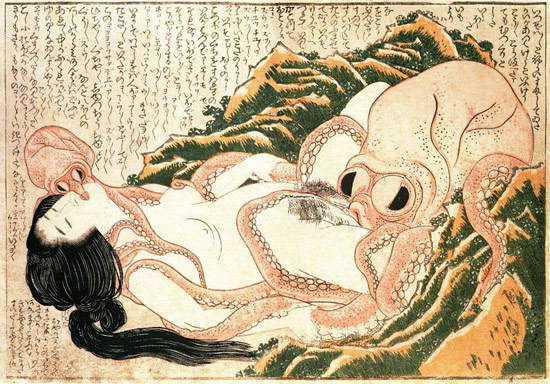

An artist of the school of floating world images (editor’s note: floating world images is the translation of the Japanese term ukiyo-e, which designates this genre of prints), Hokusai ensured the fame of his works in Japan and abroad by presenting a grandiose work of expressive recourses of unparalleled beauty that placed him alongside European Impressionists such as Van Gogh, Monet, Toulouse-Lautrec or Degas. His most representative works include The Great Wave of Kanagawa, Mount Fuji Red, The Fisherman’s Wife’s Dream and The Ghost of Kohada Koheiji.

|

| Hokusai, South Wind, Clear Sky, also known as Mount Fuji Red, from the collection Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (ca. 1830; color ink on paper, 25.7 x 38 cm; various locations) |

An image reveals contexts and meanings to us. Analyzing it more closely, Hokusai’s work is full of references to Zen philosophy and its context. Throughout his work, which takes the form of a series of cards, surimono (ndt: Japanese woodcuts often accompanied by poems), illustrated books of poetry and sketches, he portrayed the Japan of his time. Hokusai’s images of the floating world show the people of Japan a reality: to be on an island threatened by the devouring force of the sea, as happened with the 2011 tsunami.

In the 19th century, his printmaking reflects the important connection of the Japanese with the sea. Island cultures, i.e., Polynesian, Oriental, or Caribe cultures, have always had a strong relationship with marine elements. In this case, for the Japanese, the sea is a representation of a natural force that can be as refreshing as it can be threatening and cyclical.

|

| Hokusai, The Fisherman’s Wife’s Dream (1814; color ink on paper, 19 x 27 cm; various locations) |

For Zen philosophy, the universe is a balance between good and evil, yin and yang, light and darkness: these opposing forces reveal the struggle for survival in nature and the human spirit. Likewise, through his images, Hokusai represents the harmony of the universe that we must not allow to be broken. The proportions and lines of his drawings not only capture the movement and flow of the universe, but also exactly explicate this balance on the human and earthly plane.

|

| Hokusai, The Great Kanagawa Wave, from the collection Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (c. 1830; color ink on paper, 25.7 x 38 cm; various locations) |

Made with fine brushes on delicate tissue paper and in subdued tones, these paintings are not only an aesthetically curated work from the viewer’s point of view, but the process itself is similar to a ritual. We know that the Japanese lead a simple lifestyle, so much so that it has been difficult for the West to understand it. With their simplicity in clothing, food, and housing, the Japanese emphasize an aesthetic that seeks an integration with nature.

In the print of The Great Wave, one can glimpse in the background Mount Fuji, the sacred mountain symbol of Japan. Despite the agitation of the waves, the sky is kept bright and clear. It is not raining and there are no storms, a reflection of the fact that, as in Zen philosophy, one must remain calm even if a storm is in progress.

At the same time, the landscapes depicted by Hokusai show, among the mountains, inhabitants wearing typical peasant hats and sowers in rice fields. For Taoist philosophy, Japan’s mountains represent strength and omnipotence-the imposing nature before which man stands. In Hokusai’s prints, the mountains are outlined with the same subtle delicacy as those who depict ephemeral waves. Like another wave, the mountains rise up, distant and imposing, to remind us how small and fragile we are in the face of nature. The art of his paintings speaks for itself; his works convey to us the serenity and simplicity of a man who saw fit to depict the nature of his country as a work of monumental beauty.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.