A patron so splendid that he earned the appellation "Magnifico." Pandolfo Petrucci (Siena, 1452 - San Quirico d’Orcia, 1512) was one of the most powerful men in late 15th-century Siena , and his activities in the arts contributed substantially to shaping the face of the city. The Petrucci family belonged to the wealthy merchant bourgeoisie of Siena , and Pandolfo was a member of the Monte dei Nove, one of Siena’s five “parties” (although they were very different from today’s political parties: we can imagine them as institutionalized groupings, representing the interests of as many parts of the population, and dividing up the government of the city): his political career began in the 1480s, and immediately, in 1483, he was exiled from the city along with other “noveschi,” as the members of the Monte dei Nove were called (at the time of his exile, the Republic of Siena was governed by the Monte del Popolo). On July 22, 1487, he, along with other exiled noveschi, managed to return to the city in a coup d’état that, by appealing to the discontent that was rife among the citizens of Siena, overthrew the Popolano government and delivered power into the hands of the Monte dei Nove. As a result of the coup, Pandolfo, then 35 years old, was given a post in the Nine of the Guard, a body responsible for maintaining public order. This was the first stage in his glittering cursus honorum.

He held the post of the Nove di Guardia for eight years, until 1495, and in the meantime, in 1488, he married Aurelia Borghesi, daughter of Niccolò Borghesi, a man of letters, humanist, member of one of the most illustrious families in the city (from which would later descend the line that changed the fortunes of seventeenth-century Rome, with the surname, however, changed to Borghese), and one of the city’s most influential politicians. Such a marriage helped to strengthen the social and political position of Pandolfo Petrucci, who found himself in fact exercising an increasingly relevant, if informal, political action within the government of the Republic. Among the measures that Siena took under Petrucci’s impetus was, for example, the restructuring of the city’s defenses ordered shortly after Lorenzo the Magnificent’s disappearance in Florence, a key action in a period that was shaping up to be decidedly turbulent (and such, in fact, it would be). When, in 1494, Charles VIII descended into Italy and entered Siena on December 2 of that year, Pandolfo Petrucci was among those who did not oppose the French king’s entry, despite the fact that the sovereign had forced the return of those exiled from the coup of 1487: Pandolfo’s moderate line turned out to be the one able to gain the most support, even though it antagonized him the most important member of the rival faction, Lucio Bellanti, who following a further clash with Pandolfo Petrucci was exiled in 1496 on the charge of having hatched a conspiracy against him. Bellanti repaired to Florence where he was assassinated in 1499, with the suspicion that the instigator was Petrucci himself. Similarly, the suspicion that Petrucci’s hand was behind the assassination of his father-in-law Niccolò Borghesi, who was killed in 1500 after his faction took sides against a measure, decided by Petrucci himself. Pandolfo had in fact becomede facto lord of Siena in 1497 after the death of his brother Iacopo and his entry into the new Bailiwick (the main governing body of the Republic along with the consistory: members were appointed at fixed intervals by the general council, a kind of parliament): the disappearance of his brother and the exile of Bellanti, who was the other leading member of the Sienese leadership at the time (so much so that historian Maurizio Gattoni spoke of a “military diarchy” composed of him and Petrucci), made him the de facto unchallenged arbiter of Sienese politics.

In foreign policy, Pandolfo Petrucci was a central player in the events of his era. With Florence, as mentioned above, he established a truce in 1498 and the following year strengthened his position by forming an alliance with the King of France Louis XII at the time of his descent into Italy (the French were in fact allies of the Florentines). A guarantee of tranquility for Siena, but also a useful tool when the city was threatened by the expansionism of Cesare Borgia, the Valentino, at the time of his violent military campaign in central Italy. When in the summer of 1502 Borgia conquered Urbino it became clear that the cities threatened in quick succession would be Perugia and Siena. Pandolfo Petrucci was therefore among the organizers of a conspiracy (in which several prominent lords, such as Guidobaldo di Montefeltro, Ermes Bentivoglio, Vitellozzo Vitelli, and Gian Battista Orsini, also participated), later known as the Conspiracy of the Magione from the name of the city in which it was held, which, however, Valentino managed to escape. His revenge was then brutal: on December 31 of the same year, having conquered Senigallia, he invited some of the conspirators under the pretext of a reappeasement, but then had them killed after having them tortured (the event, one of the most infamous of the Renaissance, is known as the “Slaughter of Senigallia” and was the subject of a well-known treatise by Niccolò Machiavelli). Pandolfo managed to escape the massacre as he wisely decided to decline the Valentino’s invitation to Senigallia and to leave Siena at the same time (Cesare Borgia had in fact demanded and obtained that Pandolfo be expelled from the Bailiwick): in the meantime, exiled to Lucca, strengthened by the support of Louis XII and Florence (in exchange, however, for the cession of Montepulciano to his ancient rivals), he worked to return to the city, where he returned as early as March, as the king of France enforced Pandolfo’s return to Siena, which he managed therefore in a few weeks to make his entry into the city, and what is more acclaimed as a defender of the freedom of the homeland, since thanks to his political action he had succeeded in preventing Siena from coming to the end of the cities subjected to the violent actions of the Valentino. From that moment on, Pandolfo Petrucci would continue to rule without rival (and in July 1507 he was also recognized primus inter pares by the members of the Bailiwick), until his retirement to private life in February 1512, a few months before his disappearance on May 21, 1512.

As anticipated, Pandolfo Petrucci was an exalted patron of the arts, and his actions were capable of expression both in private and in public, especially after 1497, thanks to the great wealth he accumulated. Renaissance Siena bears indelible traces of his lordship, and three important architectural interventions, namely the Palazzo del Magnifico (his city residence), the reconstruction of the Basilica of San Bernardino all’Osservanza, and the interventions in the Duomo, are the main evidence of this. His palace, located on Via dei Pellegrini, was completed in 1508 to a design by Giacomo Cozzarelli (Siena, 1453 - 1515), Pandolfo’s trusted architect who was able to envision for his wealthy patron one of the most sumptuous residences of the early 16th century: despite its austere façade (which, however, was once decorated with bronze ornaments now preserved at the Palazzo Pubblico), the interior was magnificent, especially because of the decorations begun the following year.,

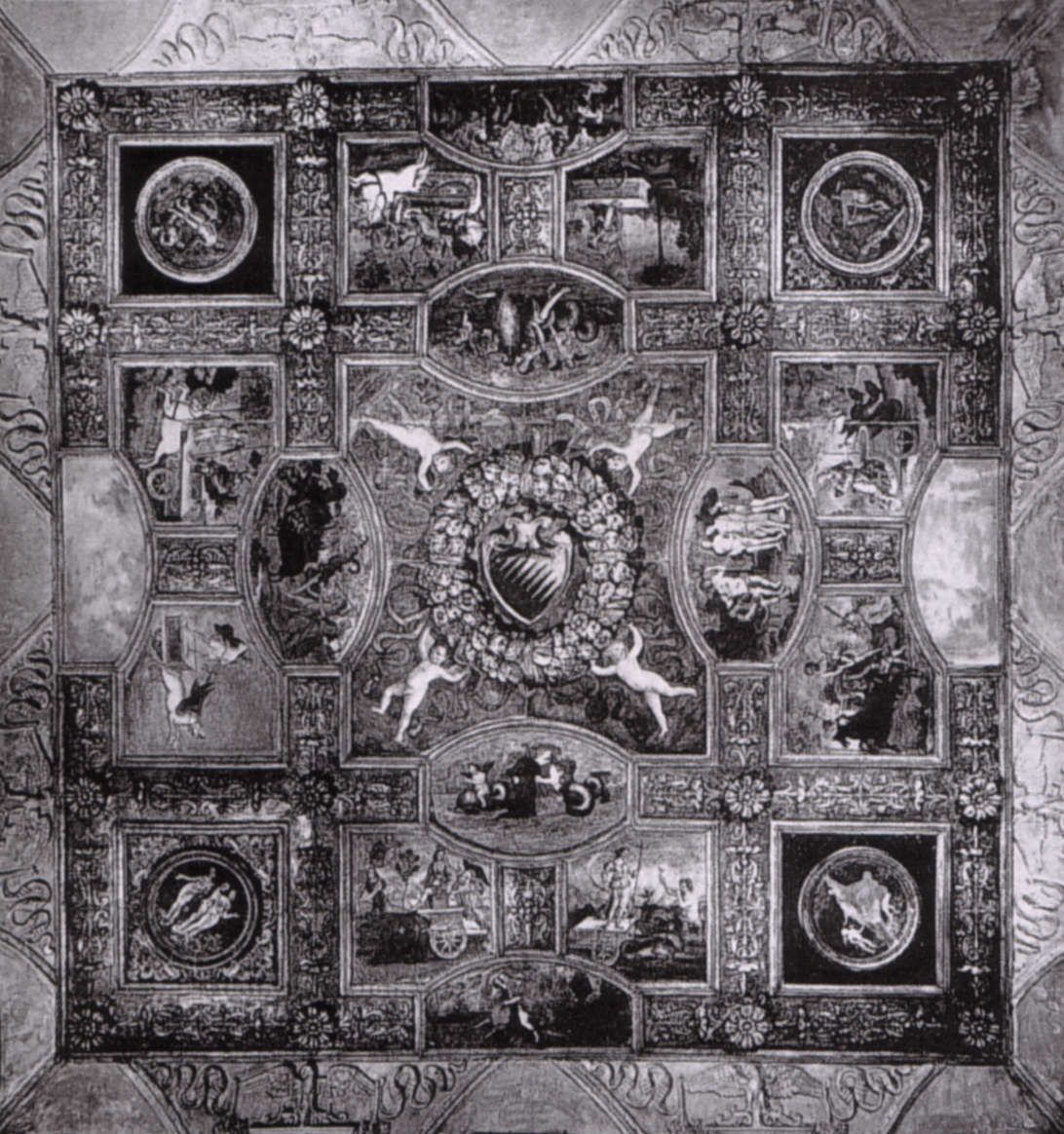

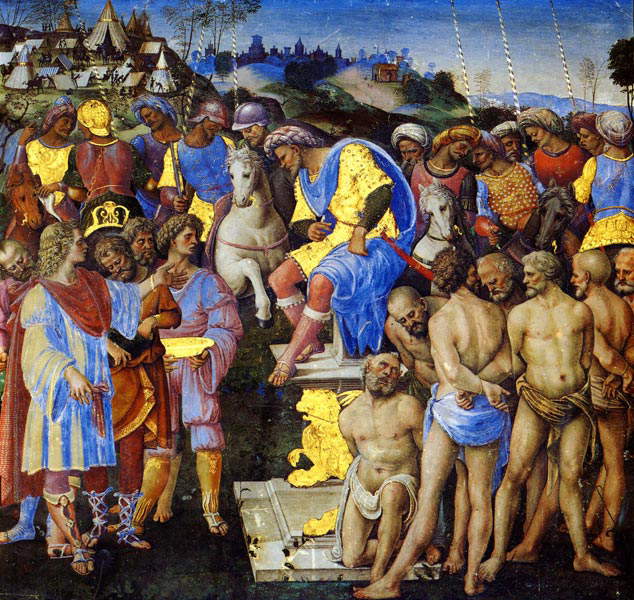

In the great hall on the piano nobile there was in fact a marvelous ceiling divided into panels painted by Pinturicchio (Bernardino di Betto; Perugia, c. 1452 - Siena, 1513), later dismembered and now preserved at the Metropolitan Museum in New York: the ceiling bore mythological scenes extolling the magnificence of the lord, divided by sculpted, painted and gilded stuccoes executed by Pinturicchio’s workshop. Similarly, Pandolfo Petrucci had had the walls of the salon frescoed by many of the greatest artists of the time, such as Luca Signorelli (Cortona, c. 1445 - 1523), Girolamo Genga (Urbino, 1476 - 1551), and Pinturicchio himself. We know the arrangement of the frescoes from the eighteenth-century descriptions: they were commissioned by Pandolfo to celebrate the marriage of his son Borghese Petrucci to Vittoria Piccolomini, niece of Pope Pius III, and were intended to celebrate the Petrucci family through allegories that referred to their exploits (Pinturicchio’s Return of Ulysses , for example, was a clear allusion to Pandolfo’s return to Siena after theexile he had to endure to prevent the city from falling into the hands of Cesare Borgia), but there was also no shortage of scenes alluding to the virtues of marriage, such as Luca Signorelli’sLove Defeated and the Triumph of Chastity , now in the National Gallery in London. Then, in the 1840s, the frescoes were detached, and today, minus two scenes by Luca Signorelli that have been lost, they are divided between the National Gallery in London and the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena, which preserves Girolamo Genga’s Ransom of the Prisoners by the Son of Fabio Massimo and the Escape of Aeneas from Troy, also painted by the artist from the Marche region. Of everything that was in the palace, nothing remains today: we can only see the building, which now houses an accommodation facility.

An itinerary on the trail of Pandolfo’s commissions could, however, continue with a better-preserved building, namely the Basilica di San Bernardino all’Osservanza, which according to critic Cecil H. Clough represents the first case of patronage on the part of the Sienese lord, dating back to 1494, the year in which the church, which stood on Capriola Hill just outside the city (and where, according to tradition, Saint Bernardine of Siena resided), was heavily damaged by lightning: it was therefore had to be rebuilt in Renaissance forms (internally still partly visible, while externally the church underwent heavy renovations in later periods), partly because Pandolfo Petrucci intended to make it the family’s burial place, in accordance with the custom of many Renaissance lords. The reconstruction bore the signature of one of the leading architects of the time, Francesco di Giorgio Martini, who enlisted the help of Cozzarelli.

The rooms of what was once the church’s sacristy were repurposed as a funerary chapel for the Petrucci family (Pandolfo’s remains, moreover, are still in the basilica). A masterpiece by Cozzarelli (who was also a sculptor) is also probably due to Pandolfo’s commission, namely the Lamentation over the Dead Christ, a sumptuous terracotta sculptural group that perhaps originally adorned the lord’s tomb, and which is counted among the most brilliant works of its kind (as well as the first example in Siena of a genre that was instead typical of Emilian art).

Returning instead to the city center, it is possible to enter Siena Cathedral to observe traces of Pandolfo Petrucci’s patronage. The interventions date from the same years when, in the adjacent Piccolomini Library, Cardinal Francesco Todeschini Piccolomini, who would become Pope Pius III in 1503, was having the walls frescoed by Pinturicchio. Petrucci’s first measure (officially taken by the college that, in 1505, had been appointed to oversee matters relating to the cathedral, and which consisted of, in addition to him, Giovanni Battista Guglielmi and Paolo di Vannoccio Biringucci) was the moving ofDuccio di Buoninsegna’s Maestà , which had been removed from the cathedral’s high altar to make room for the bronze ciborium made by Lorenzo di Pietro known as Vecchietta (Siena, 1410 - 1480) for the hospital church of Santa Maria della Scala, partly because of the great appreciation that contemporaries had for Vecchietta’s masterpiece (the work is still there today), and partly because it was normal for the time to update a church according to contemporary taste, and the bronze tabernacle responded better to this need, since with its classical forms it was more in line with the fashions of the time. Moreover, as scholar Philippa Jackson explained, “no other action of the Petrucci regime succeeded in so visibly exalting his power and his desire to impose the new Renaissance language on the city.”

Another project pursued by the college of which Pandolfo Petrucci was a member was the arrangement of the apsidal part: the idea was to demolish the wooden choir of the canons, who would be moved to the stalls of the main chapel, in order to free up the space occupied by the structure “sub pretextu maioris ornatus et decoris,” that is, “by reason of greater ornament and decorum.” The removal of the chancel from the center of the church produced an important effect, noted scholar Monika Butzek: “for the first time in the history of the cathedral the laity would be allowed a full view of the high altar allowing them direct participation in the liturgy without the obstruction of high enclosures reserved for the clergy. This must have been the main motivation that caused already in the 15th century but especially in the 16th century, during and after the Council of Trent, the systematic removal of almost all the choirs that in cathedrals and churches of monasteries and convents were still located in front of the high altar.”

Then there are other places in Siena that can be linked to Pandolfo Petrucci’s patronage. One of these is the church of Santo Spirito, which was rebuilt almost in its entirety starting in 1498 (work went on until 1530): the lord of Siena supported the Dominicans of Santo Spirito by paying out of his own pocket the sum of 800 ducats for the rebuilding of the dome and the high altar. This, however, did not prevent him from expelling them from the city on Christmas Eve 1504, as they had failed to comply with a Pandolfo measure requiring the city’s clergy and religious to celebrate liturgies despite the fact that the city had been hit by an interdict from Julius II della Rovere (an interdict is an ecclesiastical penalty that establishes the suspension of sacred services in a given place). The friars, however, were able to return shortly thereafter.

Another example of Pandolfo’s munificence is the Manto chapel in Santa Maria della Scala, although in this case the issue is rather complex. In 1508, Pandolfo succeeded in getting the hospital to have a governor favorable to him, although the decorations of the chapel were not carried out by Domenico Beccafumi until 1513, a year after the lord’s death, due to numerous delays that the project had suffered: the undertaking was therefore followed by his son Borghese. Finally, Pandolfo’s undertakings also include the church attached to the convent of Santa Maria Maddalena, dedicated to a saint to whom the lord of Siena was very devoted (she was also declared patron saint of Siena in 1494, with a palio being held in her honor). Pandolfo financed the construction of the new church (the abbess of the convent was, moreover, his cousin, Aurelia di Bartolomeo Petrucci), although the work remained unfinished at his death and the entire convent was later demolished in 1526.

It will then be necessary to mention that Pandolfo was also very interested in the ornamentation of the city: among the projects he had in mind was one for a classical portico along Piazza del Campo, the design of which, in 1508, was entrusted to Giacomo Cozzarelli, but which was never carried out due to a lack of financial resources to be allocated to the undertaking.

A munificent lord, a sumptuous patron typical of his time, he was also able to exercise his power thanks to his control of public finances, through which, the scholar Mauro Mussolin has written, “Petrucci could dispose with sufficient autonomy of the revenues of the municipality,” according to a practice that “allowed him to declare only pro forma the items in the budgets of the bodies he controlled” (and to do this “he could rely on the coverage guaranteed to him by his colleagues in government”), Pandolfo Petrucci understood patronage primarily as a means of personal promotion but also as a means of affirming the prestige of the Republic. His choices had an important echo in the city: thanks in part to Pandolfo Petrucci, the face of Siena experienced important changes in the Renaissance era.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.