One of the most curious paintings to be encountered at the Kunstmuseum in Basel, Switzerland, is an engaging scene of a bath at a spa: its author is the Alsatian painter Hans Bock (Saverne, 1550 - Basel, 1624), and the painting dates from 1597. It arrived at the Basel museum in 1872 following a purchase. The bath depicted takes place in a large tub that occupies the entire composition horizontally, and is outdoors, set in a beautiful mountain landscape (we see, in the background, the peaks of what are most likely the Alps). The pool, a kind of large swimming pool, is accessed via a small staircase on the right, from which a woman who has not yet completely undressed is descending, while along the edges run two high steps that serve as seats. Dividing the pool from the outside is a sort of wooden fence where, with great anecdotal gusto, Bock has arranged some folded clothes, left there by those who have already gone down into the water. Three men are leaning against the fence: one is carrying wood on his shoulders, and two others are nearby pointing at someone in the pool.

The pool is definitely populated, its frequenters are all naked, and the fact that surprises us most is the fact that the bathing is promiscuous: men and women bathe together and do not seem particularly bothered, on the contrary. On the left side are several of them sitting around a table eating and drinking: at the head of the table, in particular, a young woman is eagerly guzzling a glass of wine. To her left, another young woman holds a bunch of grapes and turns to face us: along with the other woman, next to the man on her left, she is the only one looking the viewer in the eye. The other characters are caught in a variety of activities: continuing the description of the people at the table, we see a woman standing with her arms folded, probably feeling left out: a man nearby, in fact, ignores her and is trying to start a conversation with the young woman next to him. Behind, on the other hand, there are those who are attempting a much more material approach: another individual, in fact, is trying to undress a young woman who, to escape his grasp, grabs the man sitting at the table. Next door, a couple is playing a wind instrument, the same activity in which a young man on the opposite side of the pool is engaged. Next to him, another couple is immersed in reading, with the man again making himself rather intrusive by hugging the girl from behind as he reads. At the edge of the pool, two women are getting dressed.

|

| Hans Bock, Bath at Leukerbad (1597; oil on canvas, 77.5 x 108.5 cm; Basel, Kunstmuseum) |

|

| Hans Bock, Bath at Leukerbad, detail |

|

| The baths of Leukerbad today. Ph. Credit Switzerland Tourism |

In the collective imagination, the custom of going to the bath s is associated withancient Rome: we hardly think about the fact that even in the Germanic area, in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the custom of going to the baths was widespread and well established. We do not know where Bock’s scene is set, but since the bath is set among the mountains, it is likely to be the spa town of Leukerbad in the canton of Valais in southern Switzerland: it was a popular spa resort from ancient times, and we know that as early as the 14th century its baths were in use (according to others, however, the location depicted by Bock could be another spa resort in Switzerland, the town of Baden in Aargau). Today, Leukerbad is one of the most important spas in Switzerland as well as one of the largest in the Alps: its thermal baths are fed by hot springs, known since the Middle Ages, that maintain temperatures between 28 and 43 degrees. And because of the possibility of bathing directly beneath the mountains, Leukerbad is a sought-after destination for international tourism.

The custom of bathing, contrary to what one might think, has very ancient origins in the Germanic area: even Tacitus spoke of it in his De origine et situ Germanorum, where the great Latin author writes that the Germans, “as soon as they awake, after having slept usually until late in the day, wash themselves, especially with warm water, since winter occupies most of the year there.” For the Romans this was a strange custom, since in Rome one went to the baths at the end of the day, before dinner: a hot bath early in the morning was therefore frowned upon, since it could be interpreted as a sign of weakness. It remains a fact that the Germans would never abandon this custom (even nowadays, the Stube culture is strongly rooted among Germany, Austria and South Tyrol), not even in the Middle Ages, a time during which hot-water baths continued and were widespread among all strata of the population, as opposed to steam baths, typical of Scandinavia, which also arrived in the Germanic area but were less usual. A special treatise had also sprung up: in Italy, an indispensable point of reference was the treatise De balneis by the Umbrian physician Gentile da Foligno (Folgino, 1272? - 1348), the first medieval medical work specifically devoted to thermal waters, which would be followed by several others (typically, each treatise described the properties of water from a certain spring or place). Usually, these treatises provided readers with accurate descriptions of the type of water, the benefits that could be derived from it, the prescriptions to be followed in approaching the thermal bath, or the ways to achieve maximum results (and, consequently, the situations to avoid in order not to run the risk of the bath becoming harmful).

It was, first and foremost, a matter of hygiene: even in the Middle Ages, contrary to what one might imagine, people were aware that bathing was good practice, and those who could tried to keep themselves clean. The wealthy had private baths at their disposal, while for those who could not afford them, the option was public baths, which were widespread throughout northern Europe (they were present in every town): they could be artificial baths, which were mostly found in indoor facilities, or, in several cases, they were Wildbäder, or natural baths, fed by hot springs, and usually outdoors (this is the case with the baths in Leukerbad). One bathed, moreover, because depending on the types of water, the healing properties that were associated with the water changed. And again, bathing also had symbolic aspects, as a purifying rite (so much so that several spas stood along pilgrimage routes), or because certain springs were believed to be miraculous. Usually, baths were separate: men and women had their own reserved pools. However, promiscuous baths were also widespread, and it was not strange for a man of the Middle Ages to bathe naked together with a woman, who was also naked, so much so that some baths became veritable hangouts, where clients used to receive harlots.

Giving an idea of what baths were like in the Germanic area is the humanist Poggio Bracciolini (Terranuova, 1380 - Florence, 1459), who in 1416, while visiting the baths in Baden, Aargau, wrote a letter to his friend Niccolò Niccoli (Florence, 1365 1437) in which we read that in the Swiss baths “anyone is allowed to go and stop at other people’s baths to visit, converse, amuse themselves, and amuse themselves, while women are seen to enter and leave the water with their bodies almost completely naked. However, there are neither keepers, nor doors, nor suspicion of evil, in many places the entrance to the bath is common for men and women, so that very often it happens to a man to run into a half-naked woman and to a woman into a naked man.” Of course, regulations forbade sexual relations in the baths, but the rules were often disregarded. This was probably one of the reasons that caused the decline of thermal baths in the 16th century: the spread of venereal diseases (syphilis was widely prevalent in the 16th century), more stringent religious morality, economic measures following certain crises (e.g., restrictions on wood consumption), and reasons of various kinds made bathing in thermal waters a much less widespread habit than it had been in the Middle Ages. Nevertheless, some resorts continued to be frequented: Leukerbad was among them, as Hans Bock’s painting might testify.

|

| Peter of Eboli, illustration from De Balneis puteolanis (mid-16th century; manuscript; Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, ms. Latin 8161, f. 8r) |

|

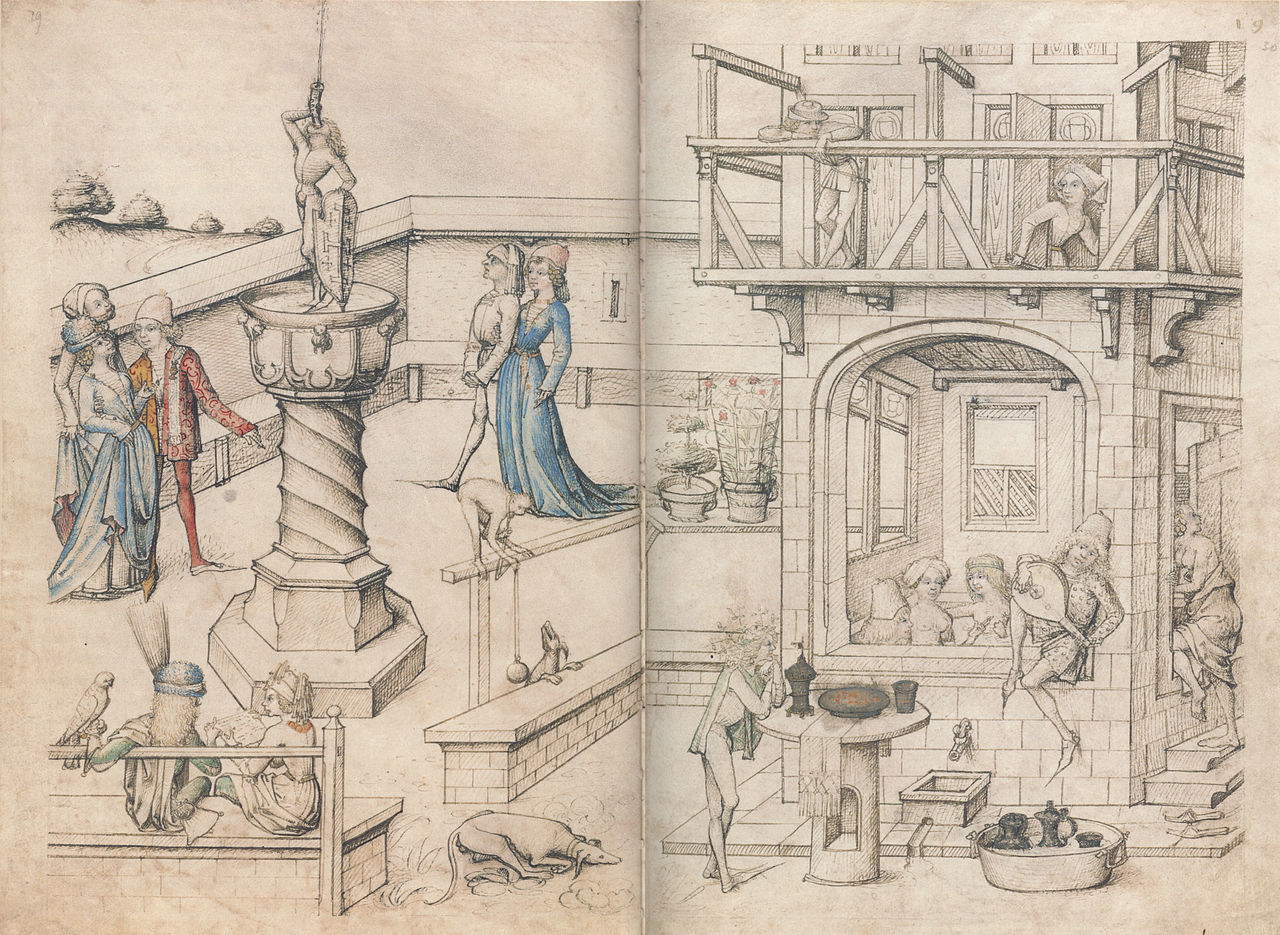

| Master of Antoine de Bourgogne, Thermal Bath Scene, illustration from Facta et dicta memorabilia of Valerius Maximus (ca. 1470; illuminated codex; Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Ms. Dep. Breslau 2, vol. 2, f. 244) |

|

| Unknown illustrator, Thermal Structure, illustration fromHausbuch ausvon Schloss Wolfegg (post 1480; manuscript; Private collection) |

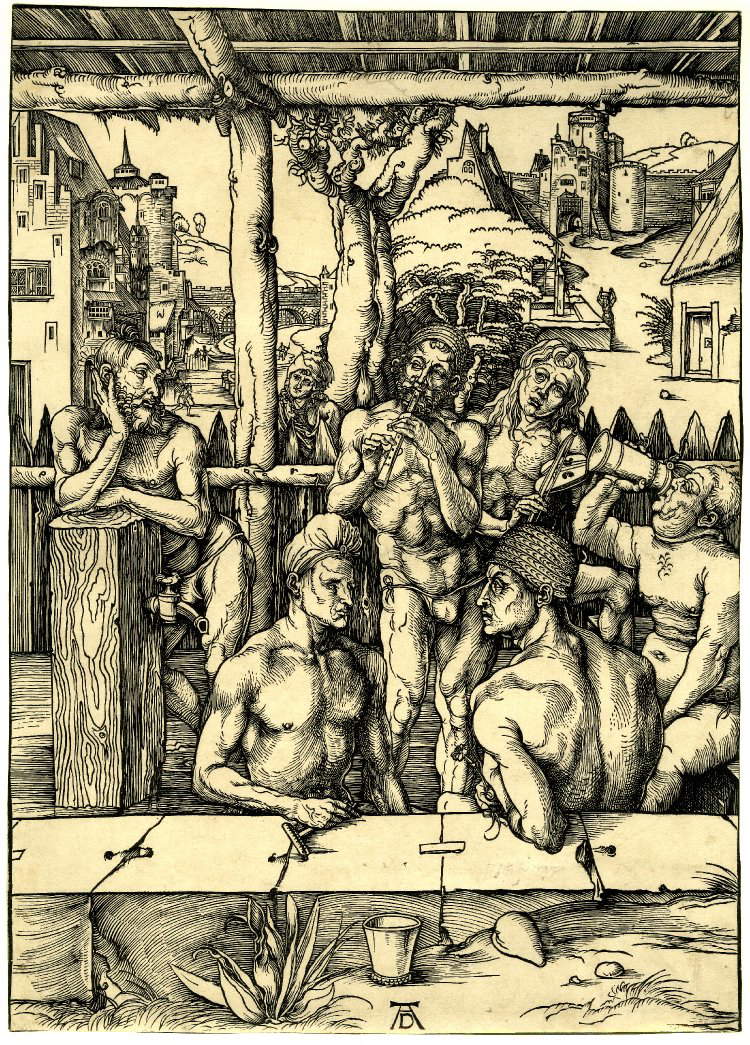

The painter in this case is primarily interested in theerotic aspect of the baths. This is, of course, not a realistic depiction, but we have to imagine that the human types in Bock’s painting were those that could be found in the baths of the Alpine spa, and that the bathers here were attending to the same activities that we see depicted in the image (including eating: it was not strange to desist directly inside the water). There are several figurative sources for Bock’s painting, beginning with a pair of woodcuts by Albrecht Dürer (Nuremberg, 1471 - 1528), namely The Men’s Bath (circa 1496-1497) and The Women’s Bath (known in several versions): the former is one of the first works made by the Nuremberg artist after his first trip to Italy, and depicts some men in a public city bath, under a high wooden portico: here too, as it will later be in Bock’s painting, there are those who play, there are those who drink (so much so that these gestures have also given rise to allegorical interpretations), and there is also a curious and ironic erotic allusion, with the man leaning against the fountain who has his genitals at the faucet, the latter having a clear and unmistakable phallic shape. Dürer’s taste for irony is also appreciated in the women’s bath: in the 1506 drawing preserved at Chatsworth we see (in addition to the sausages stuck in the spit, another sexual allusion) the tasty detail of two men who have entered to bring food to the women, and one of them, an old woman, visibly annoyed, is pouring water on one of the intruders. Some scholars have pointed out that the sculptural evidence and the almost classical proportions of the bodies drawn by Dürer hark back to the studies he had made in Italy, but it is interesting to note how the artist decided to set the whole thing in a contemporary bathroom: an element, this one, that is therefore of some documentary importance.

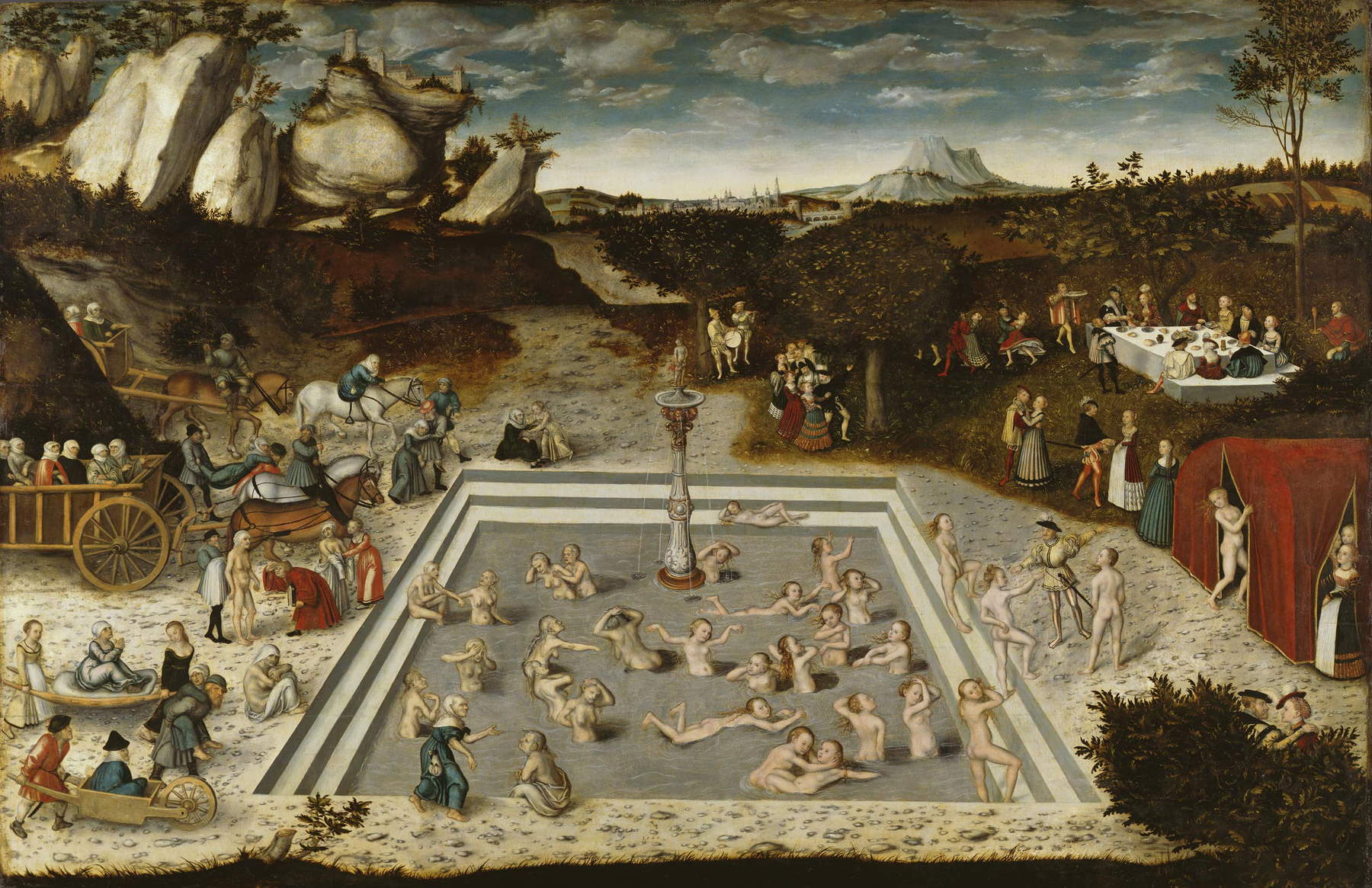

Another work from which Bock may have been inspired, especially in terms of composition, is the Fountain of Youth by Lucas Cranach the Elder (Kronach, 1472 - Weimar, 1553): in this painting, Cranach inserts a bath quite similar to Bock’s, in a central position, against the backdrop of an Alpine landscape (the difference is that in Cranach we see the whole scene from above, almost from a bird’s eye view). In the painting in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, the German painter has depicted the legendary fountain about which people in the Middle Ages fretted about the existence of a miraculous fountain whose waters were able to heal illnesses and make those who immersed themselves in it rejuvenated. The pool is populated with naked women, who enter it well ahead of their age (we see the old women as they undress on the left) and then, rejuvenated, exit it in their prime, led toward a sort of changing room by a page waiting for them at the edge of the pool. All around, there is feasting and feasting, and even, on the left, horse-drawn carriages are also continuously arriving, carrying people: as if the mythical fountain of youth was attracting organized tourism ante litteram.

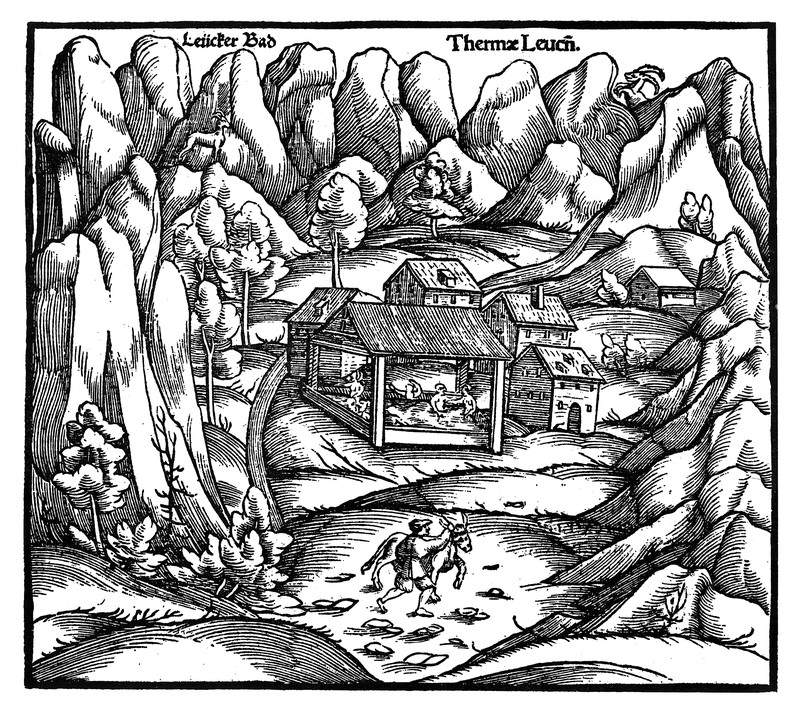

Still, another figurative source may have been the Cosmographia universalis by Sebastian Münster (Ingelheim, 1488 - Basel, 1552), a German cosmographer who, at the end of his career, taught in Basel and printed his most famous work there: the Cosmographia is, in particular, the first description of the world in German and contains some illustrations of scenes in thermal baths, and one of them is precisely a depiction of the Leukerbad baths. And then again, in what is perhaps the most famous painting by Matthias Gerung (Nördlingen, c. 1500 - Lausingen, c. 1570), titled Melancholia, dating from 1558 and preserved at the Kunsthalle in Karlsruhe, a scene set in a women’s bath can be seen.

|

| Albrecht Dürer, The Men’s Bath (c. 1496-97; woodcut, 392 x 283 mm; Munich, Staatliche Graphische Sammlung) |

|

| Albrecht Dürer, The Women’s Bath (1506; pen and dark brown ink, 285 x 215 mm; Chatsworth, Trustees of the Chatsworth Settlement) |

|

| Lucas Cranach the Elder, Fountain of Youth (1546; oil on panel, 120.6 x 186.1 cm; Berlin, Gemäldegalerie) |

|

| The Baths of Leukerbad, illustration from Sebastian Münster’s Cosmographia universalis (1550-1552; woodcut, 321 x 206 mm; London, British Museum) |

|

| Matthias Gerung, Melancholia (1558; mixed media on panel, 88 x 68 cm; Karlsruhe, Staatliche Kunsthalle) |

Finally, the presence of music deserves a final note: in the baths of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, in fact, the presence of musicians who cheered the bathers’ stay was widespread. Sometimes they were individual musicians, other times and more often they were small groups. And here the presence of music is very varied: we see in fact a lute (the character sitting at the table is playing it, whom we see from the back), a recorder (played by the character sitting next to the woman holding the sheet music) and a cromorno, or krummhorn which was very popular in the sixteenth century in the countries of the German area (and which, on the contrary, had very little success in Italy). It was a kind of flute with a curved end (the name krummhorn literally means “curved horn”) and was a double-reed instrument, a feature that places it in the family of instruments such as the oboe and bassoon. This feature, too, made the baths of the time a place intended for pleasure and sociability-elements that Hans Bock, in his painting, wanted to bring out.

Today, no baths of the time have survived, and we do not have many images of the spa facilities of the time, partly because artists usually tended to focus on aspects of life and everyday life at the baths, as is the case in Bock’s painting preserved at the Kunstmuseum Basel. Works such as these, however, are vivid evidence of customs that many believe are peculiar to our own times and that they would find hard to believe were in vogue even five centuries ago, and even earlier. The Leukerbad baths themselves, now among the busiest and most famous in Switzerland, already enjoyed the same popularity in the Renaissance as they do today.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.