“When a beautiful white girl runs into the arms of a black man, it means something is wrong. It is unequivocal proof.” So begins Love is the message, the message is death, Arthur Jafa’s masterpiece that a number of museums around the world (including Palazzo Grassi in Venice, the only Italian presence), last weekend, decided to stream free of charge for forty-eight consecutive hours. Of course, the important event was completely ignored by the Italian generalist press, despite the fact that everywhere there is an abundance of jibber-jabber about Black Lives Matter, monuments and protests that are sweeping across the ocean, often with little knowledge and little inclination to in-depth coverage. And as a result, the topic is perceived by most in its marginal and noisier contours. It is not surprising, therefore, that the work of the most recent Golden Lion winner at the Venice Biennale, despite the many discussions it has raised, has gone completely unnoticed. Unsurprisingly, it does not detract from the fact that a significant opportunity for reflection and debate has been wasted.

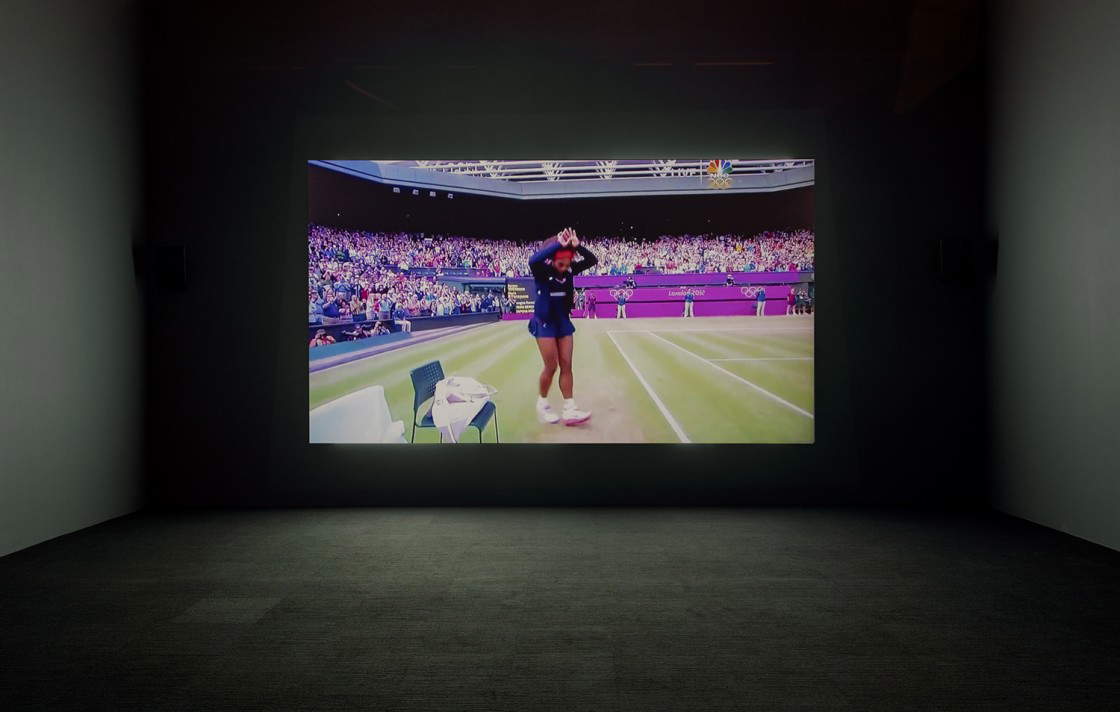

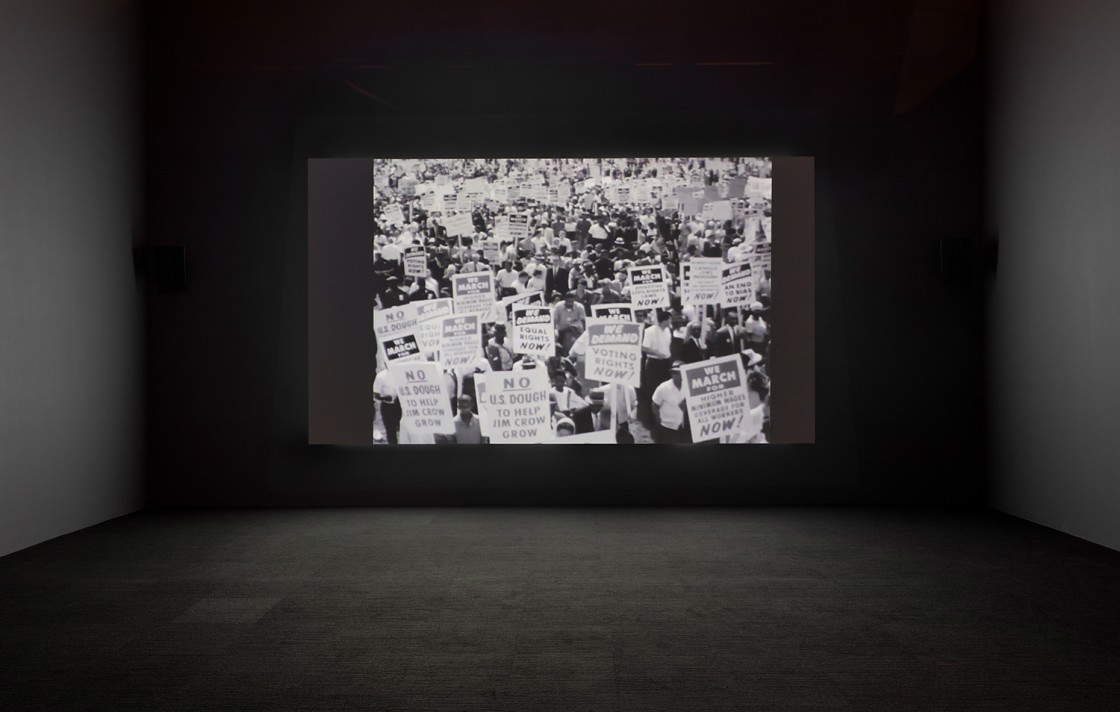

I cannot recount Love is the message, the message is death in detail: too many, too heavy and too obviousî are my cultural limitations to make an in-depth analysis of it. So I will try to summarize the content and the feelings that the video is able to provoke, and to help myself with some opinions from those who are definitely more into black culture to try to convey the importance of this work, especially in the context of the historical moment we are living through. Arthur Jafa has created a powerful masterpiece of video art that mixes different sensations, collating, with the flair of the history scholar, archivist, filmmaker and journalist together, pieces of black culture (from Jimi Hendrix to Notorious B.I.G., from Martin Luther King to Nina Simone, from Miles Davis to Aretha Franklin, from James Brown to Obama singing Amazing Grace) alternated with images of sporting feats such as those of Michael Jordan and Serena Williams, historical footage, video clips taken from social media, scenes of violence, statements from important personalities of black culture as well as from ordinary, anonymous citizens. There are exhilarating moments, touching moments (it is difficult to remain impassive when the images of Derek Redmond, the British four-hundred runner who went down in history for his injury at the Barcelona Olympics, when he tore a muscle and was helped by his father who evaded surveillance and stood over him so that he could finish the race), and others that cause tension and upset: a woman and child subjected to a police stop, police beatings, street clashes, a crying toddler forced to stand hands to the wall to see what it feels like to be stopped by law enforcement. All while Ultralight beam by Kanye West plays in the background.

|

| Arthur Jafa. Ph. Credit La Biennale Foundation |

|

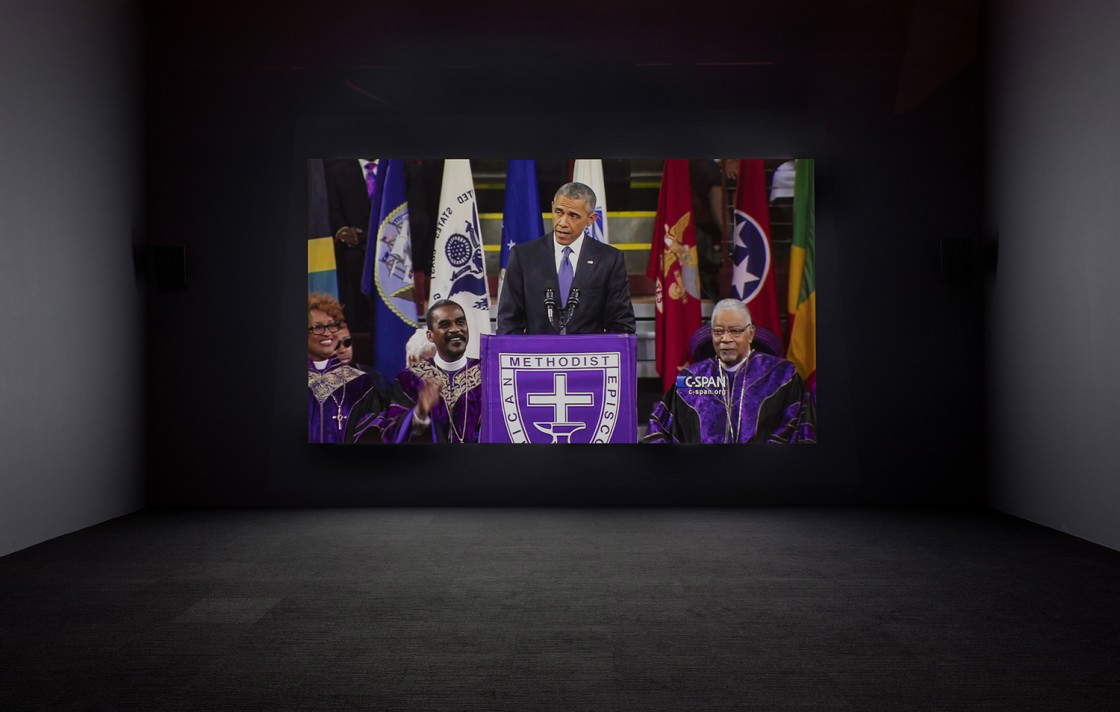

| Arthur Jafa, Love is the message, the message is death (2016; frame from video, color and black and white, duration 7’30’’) |

|

| Arthur Jafa, Love is the message, the message is death (2016; frame from video, color and black and white, duration 7’30’’) |

In the first of the two panel discussions that followed the networking of Love is the message, the message is death, Tina Campt, professor of literature and modern culture at Brown University, emphasized that Jafa insists on the historical cycles that have marked the history of the African American community, cycles within which black Americans have emerged as protagonists claiming their position within American society, the achievements of their culture, and the contribution they have made to the United States. A kind of continuous cycle that, adds Thomas Lax, curator of MoMA in New York, takes the form of a perpetual revolution, which blacks fight each time with different strategies, with new technologies of social involvement, and with the goal of continually shaping a freedom that history has denied them, and in part continues to deny them. It has been said that Jafa has the flair of the historian: and from the comments of many who have discussed Love is the message, the message is death, it emerges that the work is proposed almost as a kind of book, taking the form of a sacred text. Indeed, one can venture a consideration: what Arthur Jafa has composed is a story that transcends contingency, that composes a kind of black epic, that speaks of freedom. It is interesting to note that, speaking with Interview Magazine, Jafa recounted that he cried while making the video. “It is a test of the truths that black people know about their position within society, positive or negative. I remember when they told me that cell phones would be equipped with cameras, I thought that was the stupidest idea I had ever heard. What do you do with a camera on your cell phone? But we saw what an impact it had: it allowed mass verification of what black people were saying.”

Jafa offers us a work that eschews any conceptualism, that takes the viewer and makes him go through a florilegium of the most disparate and even opposing moods, sometimes caressing, sometimes slapping, from beginning to end provoking a feeling of alienation (typical, after all, of black art), often juxtaposing fragments in an aesthetic continuity that disorients. It is a work that could not be more true to the ambivalence of its title, since, as art critic Sky Sherwin wrote in the Guardian, the work pushes in opposite directions, simultaneously evoking feelings of freedom and terrible pain: all in the space of seven and a half minutes. It is also, if you will, a challenge to the very concept of “art,” and at the same time a powerful reaffirmation of it at a time in history when we are losing sight of the deeper meaning of art. Meanwhile, Love is the message, the message is death was conceived with the clear intention of igniting discussions: that is why until now it had only been screened in collective spaces, inside museums or galleries. But the historical moment we are going through has also imposed a public projection in the great space of the net. And so the question cannot but arise spontaneously, and it can be formulated in Tina Campt’s words, "what is the role, what is the poential of black art in this historical moment?" Answering this question means reknitting the threads of art’s civic function (regardless of whether it is born with a political intent or not: a work of art is always a text that is the result of a historical moment and that, Longhi recalled, always stands in relation to other objects), a function that has been lost in recent periods, to the advantage of its aesthetic bearing.

|

| Arthur Jafa, Love is the message, the message is death (2016; frame from video, color and black and white, duration 7’30’’) |

|

| Arthur Jafa, Love is the message, the message is death (2016; frame from video, color and black and white, duration 7’30’’) |

|

| Arthur Jafa, Love is the message, the message is death (2016; frame from video, color and black and white, duration 7’30’’) |

It is undeniable that art provokes emotions. But the work of art, we recalled on these same pages, remains however and always a political act, because in order to process emotions (which are not only an aesthetic fact: emotions are about our lived experience) it is necessary to interpret, it is necessary to give an order to the images. And here, the power of the images (and of black art in general) lies in their ability to seamlessly disturb, to get us out of our comfort zone, to put the relative in the conditions of trying to understand the terms of the disagreement between black culture and violence. I think the point of it all is summed up in a phrase that can be heard uttered roughly halfway through the video by actress Amandla Stenberg, who wonders how “what would we be like if America loved black people as much as it loves black culture?”

But underlying this work is more: the viewer is led to wonder what the image of the sun burning means, and which recurs often, especially at the end of the film. They are, moreover, the only images that are the result of digital processing, and not shot with ordinary equipment. The sun sums up the meaning of everything Love is the message, the message is death. And this was explained by Arthur Jafa himself in an interview with Frieze a couple of years ago: "much of the video is not composed of found footage. There are iconic moments that I shot myself: the little boy landing on his back in slow motion is my son, the wedding is my daughter’s, the old woman dancing at that wedding is my mother. That said, the sun is the most appropriate scale to consider what is happening. It is basically a statement about the fact that black lives should be considered on a cosmological level. I get frustrated when people talk about this video in the narrow terms of Black Lives Matter. I can’t deny that there are relationships, but it’s also a work that has to do with ecstasy, with redemption, with Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s St. Teresa. I see black lives in epic, mythic terms. And on a simpler level, I would like you to look at what is happening to black people not by looking down, but by looking the same way you would look at the sun."

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.