One of the most famous works by Luc Tuymans (Mortsel, 1958) is a huge Still Life, measuring three and a half by five meters. It is perhaps the largest still life in the entire history of art. It is certainly one of the Flemish artist’s most challenging achievements (as well as being the largest work he executed), as well as one of the most profound. To look at it, one would not guess that those seemingly insignificant objects, namely a bit of fruit, a couple of plates and a pitcher of water, actually spring from one of the most tragic events in recent history. It is 2002, Luc Tuymans is asked to exhibit at Documenta 11 in Kassel, and the event, curated that year by Okwui Enwezor, ends on September 15, just days after the first anniversary of the September 11, 2001, massacres.As a result, the German exhibition is marked by strong political and social connotations, and audiences and critics alike expect Tuymans to also offer a work fully centered on these themes. Instead, the painter presents his giant still life. It was the most immediate way the artist had found to respond to the horrendous event of a year earlier. “My wife and I were in the U.S. during the September 11 attacks,” Tuymans explained at a major solo exhibition held at London ’s Tate Modern in 2004. “Of course we were shocked. What could one do in the face of all those images that were constantly being replayed at every turn? At some point they had become disgusting. So I had the idea to do something different. To do something to counter those images. I went back to the idea of the idyllic. To the idea of this still life. But exaggerated in size, so that it could shock the viewer [...]. This still life offers an image to the viewer, but at the same time it destroys it. It disintegrates it to the extent that it presents itself with this grandeur.”

One of the key terms for understanding Tuymans’ poetics is "inadequacy.“ The painter felt somewhat inadequate in the face of the flood of images that assailed him during the days of the attack and in the weeks that followed. ”The September 11 attacks,“ he said, ”were also an assault on aesthetics." Hence, the need to respond. With an ordinary, familiar, almost mundane painting. But altered in its dimensions so as to become disorienting: the relative feels the same sense of inadequacy when confronted with that image. Not only that: the large Still Life represents an attempt at sublimation, a way of replacing the violence of certain images with a series of objects designed to evoke different sensations. Yet, that image itself becomes a kind of brand of violence, since it stands as a way to replace images of tragedy. It is in this sense that Tuymans’ strategy is fulfilled, which confronts us with the way we relate to images: the artist, wrote critoco Ronan McKinney, “does not assert the unrepresentability of 9/11, nor does he produce an image that invokes the event. On the contrary, Tuymans investigates the capacity of the image to represent more than what it makes visible, so as to present the unrepresentable not beyond representation, but always hidden in representation, always while it haunts representation.”

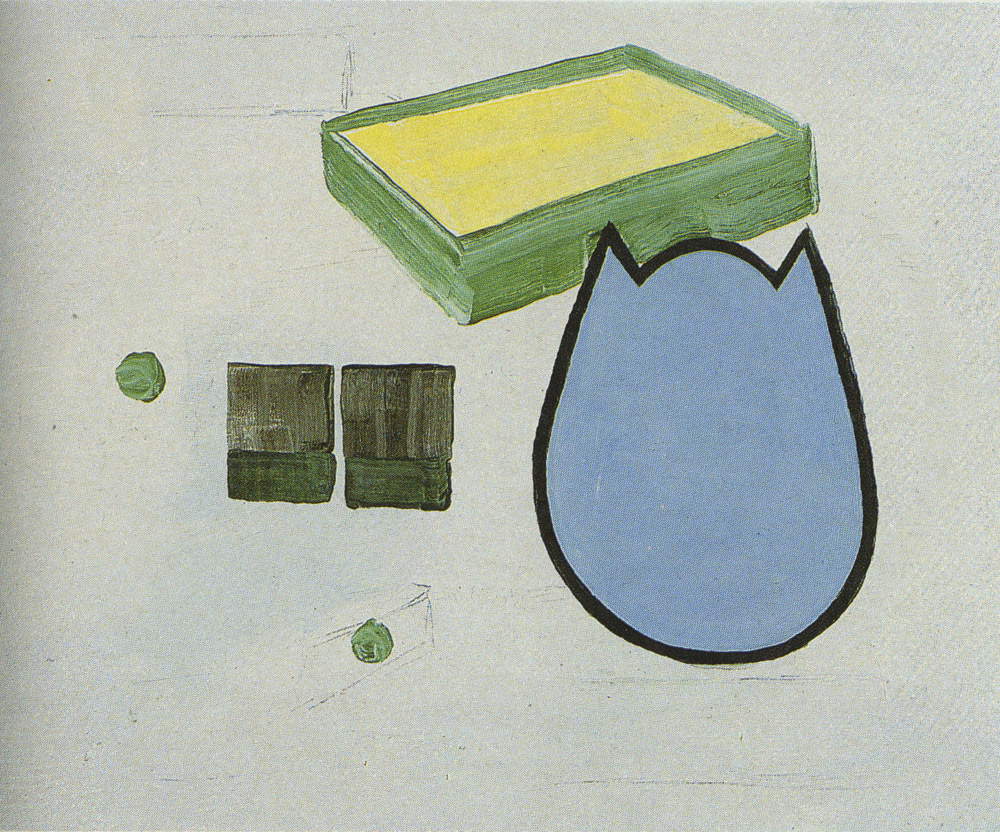

These mechanisms have always been part of Luc Tuymans’ art from the very beginning. Particularly dense is a work such as Ganzen (“Geese”), from 1987: seemingly a childish painting, reproducing a poster that Tuymans had hung in his room as a child, it actually conceals a deep unease, since that poster instilled fear in him. And it is precisely this unease that makes its way into Tuymans’ art. It is an unease that hides even behind the most ordinary objects, that crawls through the simplest everydayness, that bites from behind an innocuous-looking appearance. A painting showing an ordinary image, consisting of a box, some kind of logo (a tulip or a cat’s head), a lawn, and two blobs of color that look like two balls, is titled Child abuse: the sense of the painting is that disturbing and painful stories may be hidden behind a seemingly normal reality.

|

| Luc Tuymans, Still life (2002; oil on canvas, 347 x 500 cm) |

|

| Luc Tuymans, Ganzen (1987; oil on canvas, 80 x 120 cm; Ostend, Mu.ZEE) |

|

| Luc Tuymans, Child Abuse (1989; oil on canvas, 55 x 60 cm) |

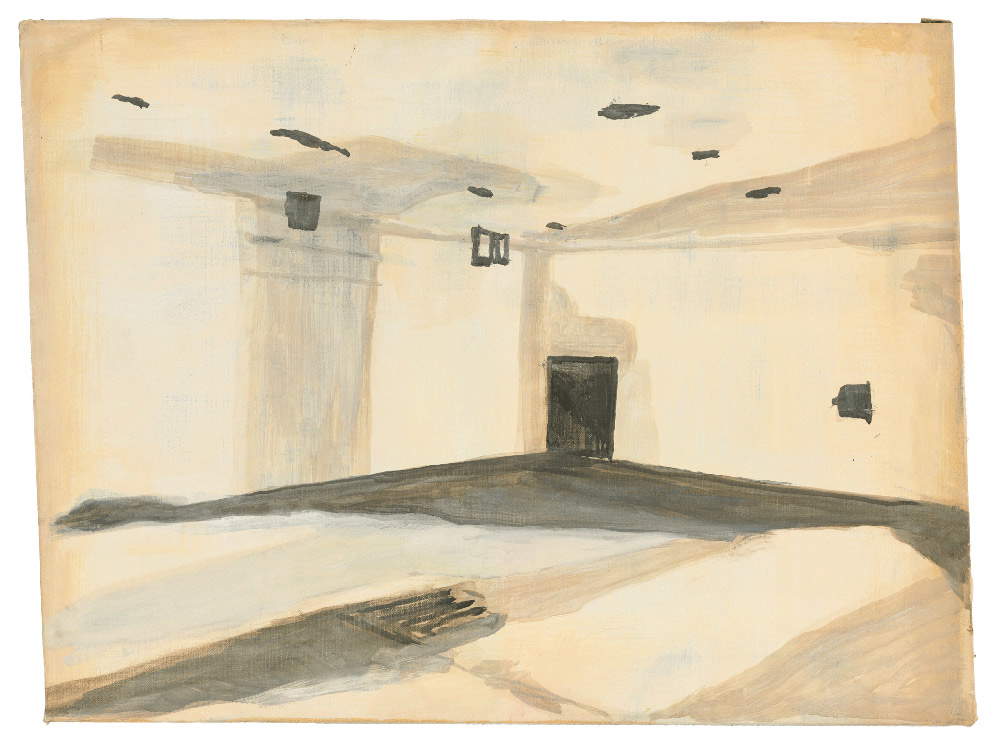

And to look for these disturbing stories, Tuymans often did not even have to look far. The artist recounted how one evening when he was five years old, during a dinner party at his grandparents’ where the whole family was present, his mother’s brother began flipping through a photo album, from which he dropped a picture depicting one of the painter’s paternal uncles, also named Luc, as a boy doing the Roman salute. The painter’s mother, a Dutch woman, had been part of the Resistance in her country and had helped hide many political persecuted people. His father was thus forced to admit that two of his brothers were part of the Hitler-Jugend. The episode had important repercussions on the smooth running of Luc Tuymans’ parents’ marriage. And, of course, on his own artistic production, which repeatedly grappled with the theme of World War II. In this sense, one of the most famous works is Gaskammer (“Gas Chamber”). It was created by the artist in 1986, and again Tuymans depicts the horror hidden behind an apparently simple room. An empty, windowless room dominated by dull colors-brown, beige, and black. On one wall, almost in a corner, a door appears, on the floor in the center of the room we see a grate, and on the ceiling indefinite brown stains. Reading the title, the reference immediately becomes clearer: Gaskammer. A gas chamber, a place of horror and atrocity, where thousands of people deported to concentration camps were killed: the artist visited them firsthand, he was in Mauthausen, and it was there that the inspiration for this painting arose. What seemingly looked like a basement actually turns out to be a place of death. The colors themselves tend to express, once again, this sense of inadequacy that the artist feels in the face of an enormous tragedy, the most immense in human history. They are not only drab, almost faded, but they are also spread with flickering brushstrokes, as if the artist felt a sense of anguish at the very moment he was painting. “It is perhaps the most problematic painting I have ever done,” said Luc Tuymans, again at the Tate Modern exhibition. And the biggest problem is roughly the same one the artist would face in the aftermath of 9/11: “the content is horrendous, but on the other hand the painting has its own aesthetic value. And that’s what I was interested in: piercing this taboo.”

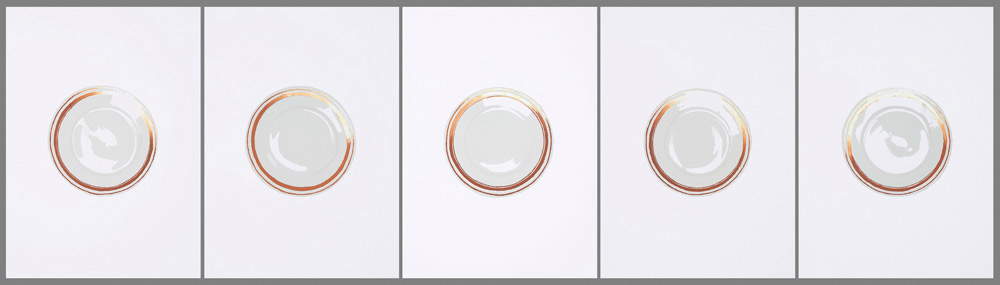

This apparent simplicity highlights in a profound way the everyday habit of provoking death to defenseless and innocent people with unthinkable coldness. And at the 2004 exhibition, this everydayness of tragedy was emphasized with the display of Plates, a 1993 painting showing five porcelain plates, similar to those Tuymans himself would later paint in the 2011 series of the same name, now housed at MuHKA, the Antwerp Museum of Contemporary Art. The series depicts five porcelain plates from the artist’s personal collection: these are products of Croatia’s ceramic industry, made when such production represented national pride, during the communist period. The series was used to create a mural for the Allo exhibition held in the rotunda of the Metrovic Pavilion in Croatia in 2012, an exhibition organized by the Institute for the Research of the Avant-garde and HDLU in Zagreb, in collaboration with the David Zwirner Gallery in Cologne, with which Luc Tuymans has long collaborated. And exhibition in which the 2011 plates served the same function as the 1993 ones: to evoke a bourgeois, simple, everyday interior, to suggest to the viewer, again, how banality often conceals atrocious secrets. The Nazis who were guilty of the greatest crime against humanity in history, after all, were not monsters who arrived from who knows where. They were very ordinary people, who outside the death camps led quiet, average middle-class lives. Tuymans’ paintings, in essence, become almost an iconographic transposition of Hannah Arendt’s theses.

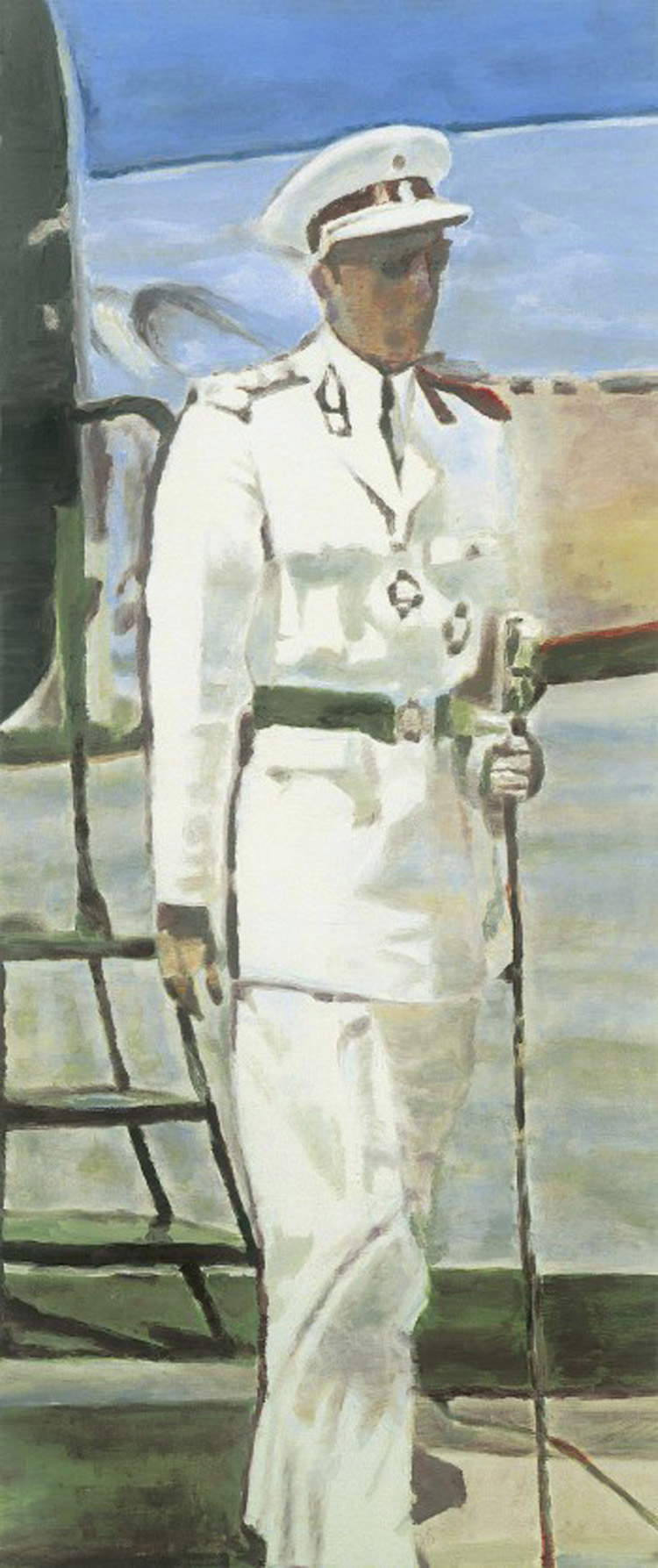

The uniqueness of Tuymans’ works consists precisely in his ability to represent facts and events of collective history, often tragic ones, by focusing on superfluous details, undefined patches of color, which at first glance do not refer to the real meaning of the work. Unrepresentable themes such as the Holocaust, xenophobia, colonialism and many others are told in Tuymans’ masterpieces through unrecognizable details, which in immediacy make their true reading imperceptible. In this sense, Luc Tuymans’ entire artistic activity becomes an allegory of contemporary memory, where private memory and collective meaning, image and time appear distant from each other, difficult to relate. In an interview, the artist stated that the title itself is the heart of the image and can never be painted: it is the absent image. The relationship between Tuymans and history is well represented by this statement, which tells us about the inability and impossibility of the representation of collective memory, which, however, only through the title of the image can be understood. Another theme of unrepresentable collective memory is Belgian imperialism in the Congo, a theme with which the artist measured himself at the 2001 Venice Biennale by bringing the series Mwana Kitoko to the lagoon. Beautiful White Man. In the best-known painting in the series we see depicted a man in a white uniform, distinguished, wearing sunglasses, probably having just stepped off an airplane that can be glimpsed behind him. The man is actually King Baudouin of Belgium, who in 1955, at the age of twenty-five, went to the Congo for an official visit. “Mwana kitoko” was the nickname the Congolese had bestowed on the young ruler, with derisive intent: “mwana kitoko” in fact means “pretty boy.” Belgian authorities, unable to tolerate what appeared to be an insult, seized the opportunity to change the nickname to “bwana kitoko,” “handsome man,” but also “man of noble appearance.” Tuymans, with the title of the work, intended to restate the point of view of the colonized.

The idea of bringing this work to the 2001 Biennale was due to a specific event: at the time, a commission had just begun investigating Belgium’s possible involvement in the 1961 assassination of the founder of the National Movement of Congo, Patrice Lumumba. Tuymans felt it was important to show the public a number of works that harkened back to the country’s history and particularly to Belgium’s imperialist past. As was his custom, however, he did not do so directly, but tried to indirectly depict images that were associated with Belgian colonialism. A theme from the past that was nevertheless carrying consequences in the present. The purpose of the work then was to evoke a historical moment, a particular situation, offering visitors multiple lines of thought.

|

| Luc Tuymans, Gaskammer (1986; oil on canvas, 50 x 70 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Luc Tuymans, Plates (1993; oil on canvas; Private collection) |

|

| Luc Tuymans, Plates (2011; lithographs, 70 x 50 each; Antwerp, MuHKA) |

|

| Luc Tuymans, Mwana Kitoko (2000; oil on canvas, 208 x 90 cm; Gent, SMAK - Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst) |

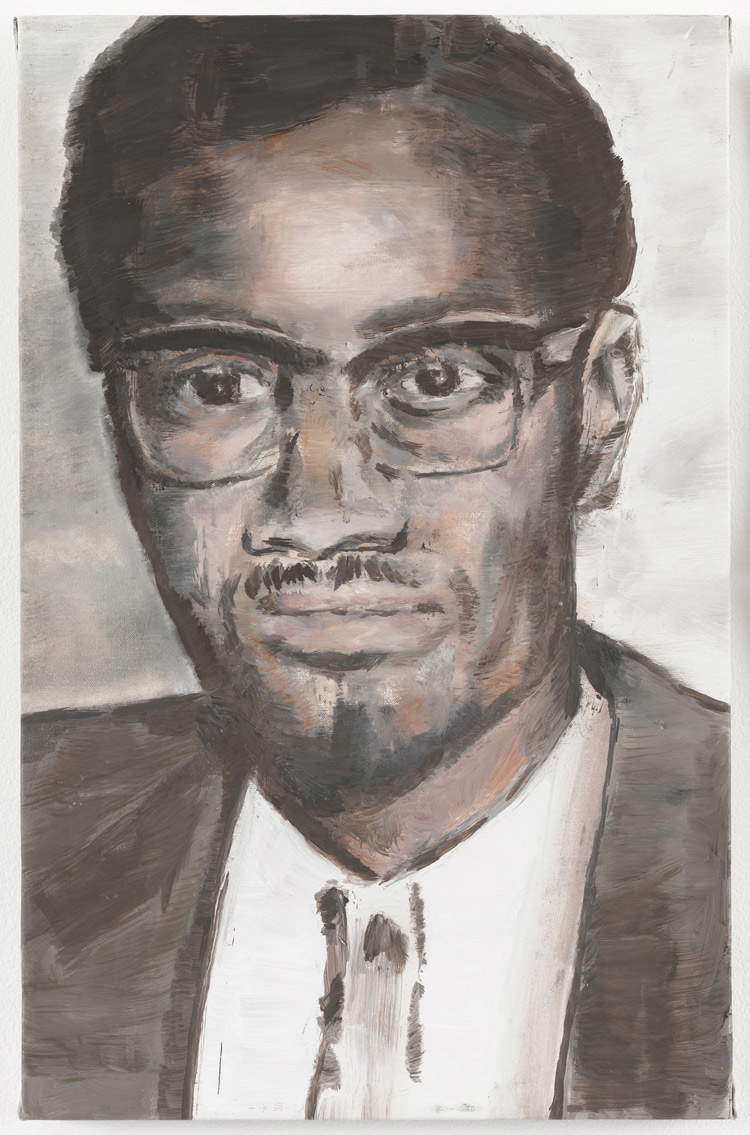

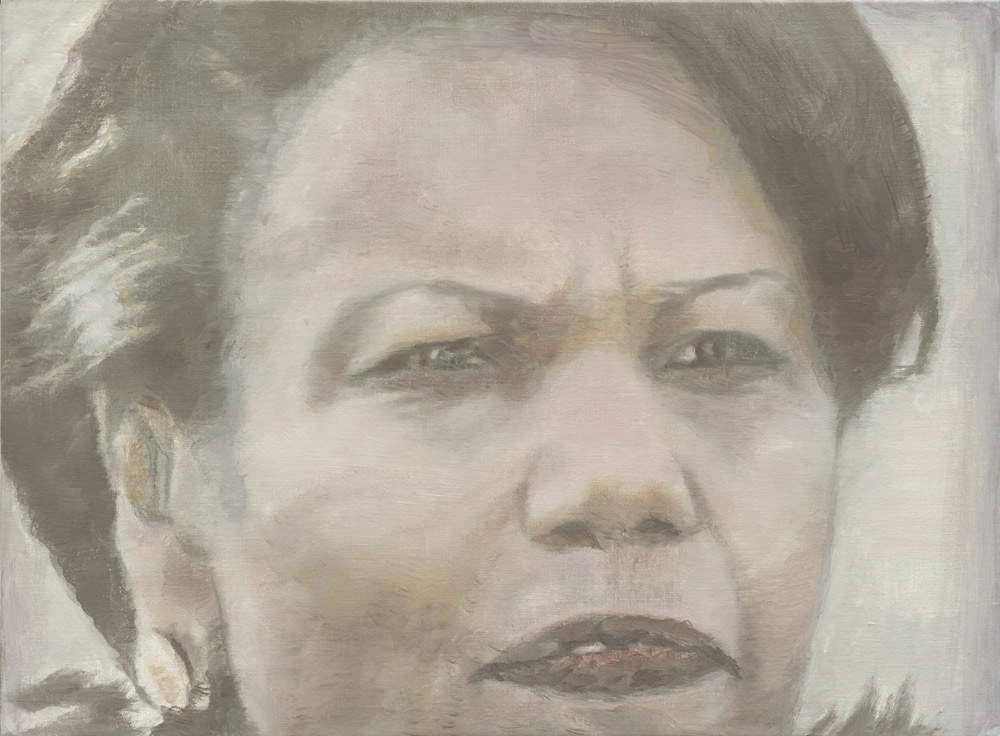

Patrice Lumumba himself was depicted by Tuymans in 2000, in a portrait preserved today at MoMA in New York, and made from a photograph of the then prime minister of the Democratic Republic of Congo. It is a painting inspired precisely by the issue raised in 2000, when, as mentioned above, Belgium was accused of having been directly involved in the brutal assassination of Lumumba, the first democratically elected prime minister in the country’s history: as is well known, the events that led to Lumumba’s assassination eventually led to the establishment of Mobutu’s 30-year dictatorship. The portrait does not add anything about the figure of Lumumba or even the history of the Congo, but it does bring to the public’s attention the issue related to his assassination, and Luc Tuymans has made Lumumba’s skin brighter in the painting and also altered his gaze by making it somewhat questioning, probably to make the viewer reflect on the hidden meaning of the portrait: historical memory. Another prominent figure portrayed by Tuymans is Condoleezza Rice, depicted in 2005. In that year, Rice was described by Forbes magazine as the most powerful woman in the world, as she replaced Colin Powell in the post of U.S. secretary of state. The painting is similar to a photograph, to one of those photographs found in history books depicting leading figures from a past history. Here, however, we have a woman from the present. Her gaze is detached and she appears focused on something undefined, a feeling also evidenced by a grimace of the mouth. Rice’s portrait, at the time of its creation, was interpreted by the public as the artist’s criticism of the Bush administration, but Tuymans portrayed her as a charming, strong and intelligent woman: and moreover, Condoleezza Rice had been the first African-American secretary of state in U.S. history. Yet this close cut, lingering on facial details, does not make the woman appear closer to us: we still feel a sense of detachment.

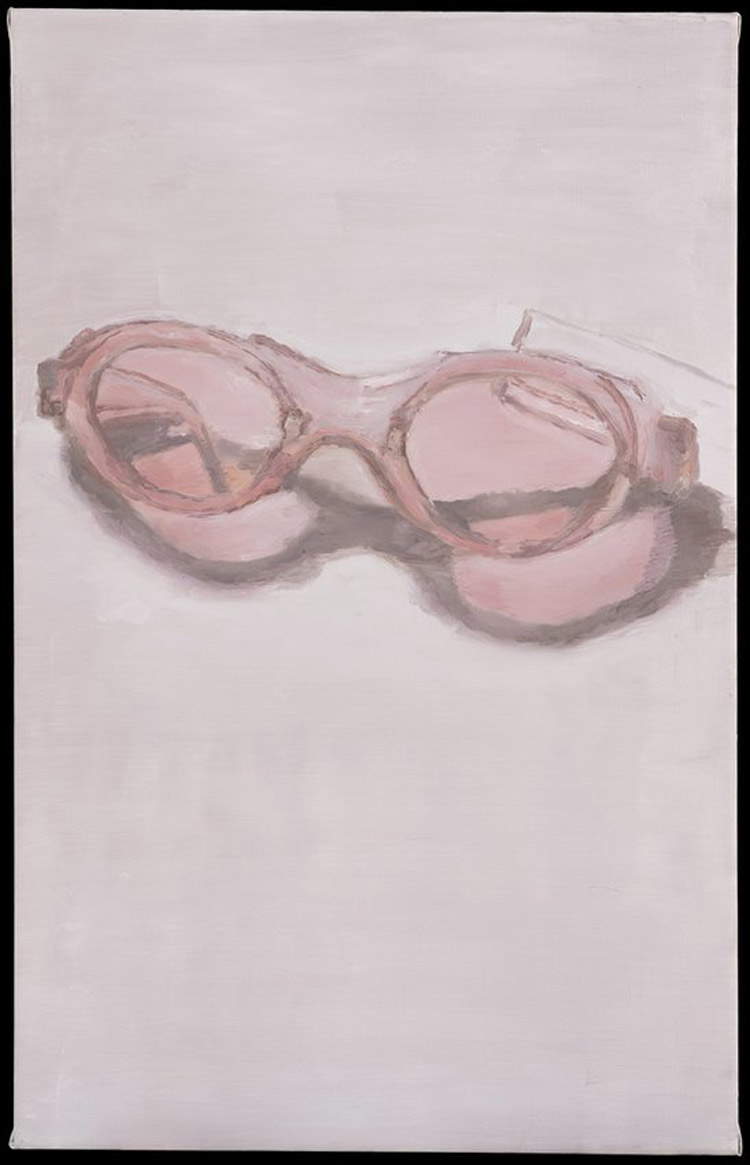

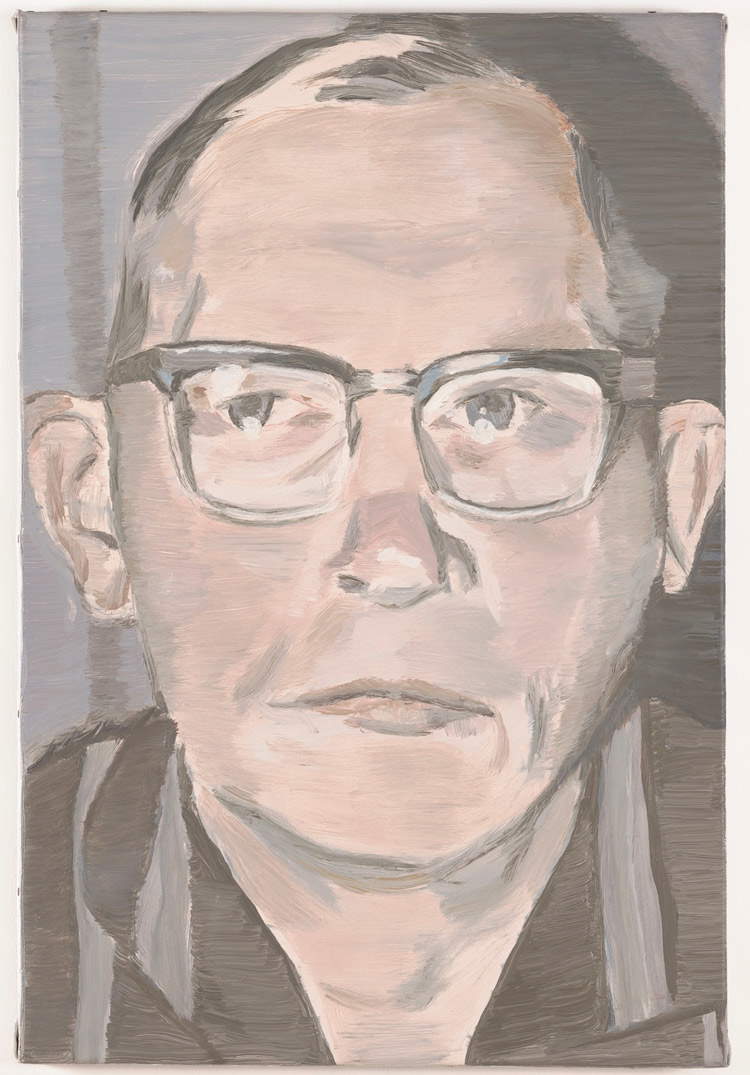

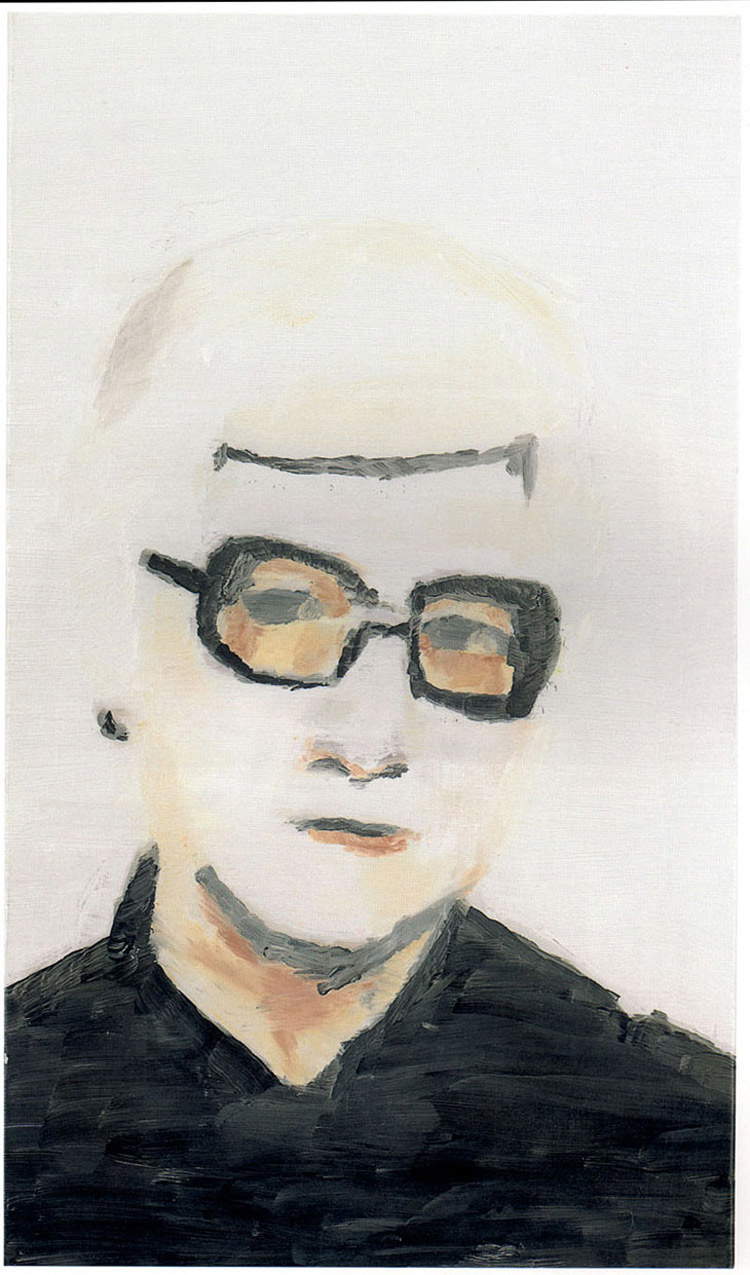

A curiosity about the portraits made by Luc Tuymans is that many of them-more than three-quarters of the subjects depicted-wear glasses. So much so that in 2017 an exhibition, titled Glasses, was hosted at the National Portrait Gallery in London that focused entirely on the glasses he depicted. These include 2001’s Pink Glasses, a simple portrait of a pair of glasses that throws us into the dimension of a blurred, ordinary everyday life, or 2000’s Portrait and 1992’s Der Diagnostische Blick II. The latter portrait is part of a series that deals with the theme of illness and the sick body. Specifically, it is a series of ten paintings depicting different people, mostly middle-aged men, and derived from as many medical photographs of subjects presenting symptoms of various diseases. Tuymans was attracted to this material because the photographs expressed the detachment of the medical observer. He also altered the gaze of the people portrayed by making it more suspicious of the viewer: they are therefore portraits that do not convey anything, neither suffering nor pain, and above all, as could also be seen in the portrait of Condoleezza Rice, the artist renounces any attempt at psychological introspection, since, according to Tuymans’ vision, the mind of the subject depicted is impenetrable. Portrait of 2000, on the other hand, is taken from a funeral photo, a memorial image: the pale and faded face, with almost undefined contours, and the melancholy expression refer to the themes of death and illness, but it is still a detached portrait, where the protagonist appears simply as a figure dressed in a black dress and wearing a pair of thick black glasses.

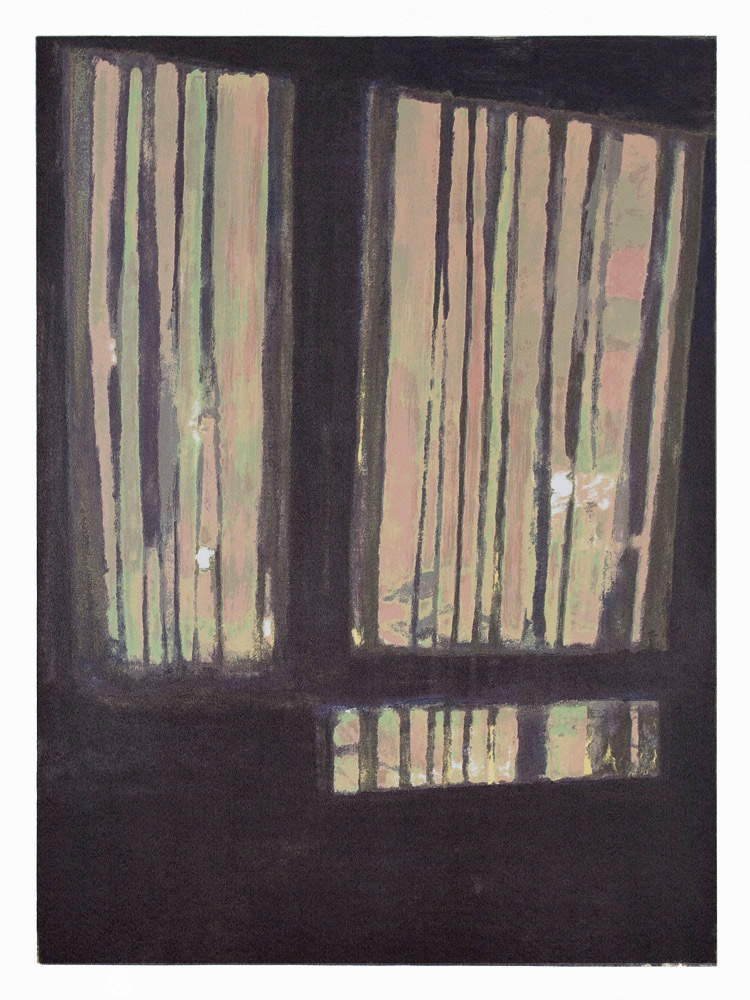

The artist’s latest research does not deviate from the elements that have always characterized his art. The 2016 Doha series, for example, made for that year’s Montréal Biennial, exactly 30 years later would almost seem to reproduce the same cliché as Gaskammer’s: bare interiors, empty walls of a museum (the Al Riwaq gallery in Doha, Qatar, which had hosted a solo show by the artist in 2015) that evoke a sense of melancholy. Like that evoked by another recent work of his, 4 PM from 2011, kept at MuHKA in Antwerp and also the result of a direct experience of the artist when he stayed in Malmö, Sweden, in 2009, again for a solo exhibition. The dark interior of a room, at four o’clock in the afternoon, into which only the lights of the city filter, almost seems to place a barrier between those inside the room and the world outside, with its stark color contrasts: one gets a sense of alienation from it.

-- lumumba. rice. pink glasses. diagnostic. portrait. doha. 4 pm --

|

| Luc Tuymans, Lumumba/em> (2000; oil on canvas, 62.2 x 45.7 cm; New York, MoMA - Museum of Modern Art) |

|

| Luc Tuymans, The Secretary of State (2005; oil on canvas, 45.7 x 61.9 cm; New York, MoMA - Museum of Modern Art) |

|

| Luc Tuymans, Pink Glasses (2001; oil on canvas, 95 x 59 cm; San Francisco, SFMOMA) |

|

| Luc Tuymans, Der Diagnostische Blick II (1992; oil on canvas, 58.2 x 39.7 cm) |

|

| Luc Tuymans, Portrait (2000; oil on canvas, 57 x 30 cm) |

|

| Luc Tuymans, the Doha series at the 2016 Montreal Biennale. Ph. Credit Daniel Roussel |

|

| Luc Tuymans, 4PM (2011; oil on canvas, 70 x 56 cm; Antwerp, MuHKA) |

In addition to his work as a painter, Luc Tuymans has long been successfully working as a curator. In 2016, for example, he was in charge of a major monograph devoted to James Ensor, one of the most important painters in Belgian history, who was being read through Tuymans’ eye for the occasion. For 2018, however, the artist was invested with the role of curator for the exhibition Sanguine | Bloedrood. Luc Tuymans on Baroque, on view at MuHKA in Antwerp from June 1 to September 16, 2018. It is an exhibition that offers the public a selection of works by seventeenth-century artists (from Caravaggio to Rubens, Velázquez to van Dyck) put in dialogue with contemporary artists, Flemish and non-Flemish (such as Edward and Nancy Kienholz, Michaël Borremans, Jan Fabre, Lucio Fontana), always in accordance with Luc Tuymans’ vision of art history and contemporary art. And it could not be otherwise, after all: Tuymans is an artist, and not a curator. It follows that privileged point of view is that of the artists themselves, since the stated purpose of the review is to “bring together ancient and modern artists in a single mental space: the inner world of an artist’s attention.”

Curating is, after all, also an extension of Luc Tuymans’ artistic activity, although the painter has remarked that none of the exhibitions he has curated have stemmed from his own volition, but simply from the fact that someone asked him to do so. But he also pointed out in an interview that curating “is interesting because it gives me the opportunity to work with art that I did not create,” and that an artist who is a curator can move the project in a direction that a curator who has never produced art himself would not be able to take. Many curators, for Tuymans, focus too much on the historical aspect and too little on the visual. An interesting observation, coming from a painter recognized as one of the world’s most influential. Partly because he was one of the artists who had the ability to catalyze interest in painting at a time when this medium had lost some of its appeal and importance. And then because, critic Ben Eastham has pointed out, “the complexity of his paintings and their union of ambiguity and detachment conflicts with the preponderant shift toward the iconic, the graphic, and the sensational in today’s image-making. ”In contrast to much of contemporary art, Luc Tuymans’ painting stands as reflective, quiet, melancholy, dull, and meditative, yet it does not fail to create heavy upheavals in those who view his paintings.

Luc Tuymans was born in 1958 in Mortsel, near Antwerp, Belgium. He studied at the Hogeschool Sint-Lukas in Brussels (one of the most important fine arts academies in the country), the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Arts Visuels de la Cambre in Brussels, and the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp. Active since the 1970s, he abandoned painting for a short period (between 1980 and 1982) to devote himself to filmmaking. He then resumed studying art history and painting, becoming one of the world’s most highly regarded contemporary artists, having helped revive the art form of painting. In 2000 he was the artist selected for the Belgian pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Before that, in 1992, he was first invited to Documenta. His solo exhibitions have been held at Tate Modern in London, Haus der Kunst in Munich, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. In Italy he has exhibited in group shows held at Palazzo Grassi, Castello di Rivoli, and Villa Manin in Codroipo. His works can be found in the world’s leading contemporary art museums, from MoMA in New York to the Museum für Moderne Kunst in Frankfurt, from the Centre Pompidou in Paris to the National Gallery in London.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.