To those not very familiar with seventeenth-century Genoese painting, the name of Luciano Borzone (1590 - 1645) will perhaps say little or nothing. Too many circumstances have played against the fortunes of this artist, beginning with the fact that his production is confined to a purely local sphere, and that some of the most admiring works are hidden from the eyes of most as they belong to private collections. However, when one has the good fortune to stand before one of his paintings, the force andintensity of his art hardly leave observers indifferent. Few artists, in the Liguria of the time, showed such a forthright and powerful adherence to the naturalism in vogue at the time. The first monographic exhibition dedicated to the artist ("Luciano Borzone. Pittore vivacissimo nella Genova di primo Seicento"), being held in Genoa at Palazzo Nicolosio Lomellino di Strada Nuova until February 28, 2016, is credited with bringing some important and unmissable pieces of this vivid naturalism to the public’s attention, since many of the paintings on display come precisely from private collections.

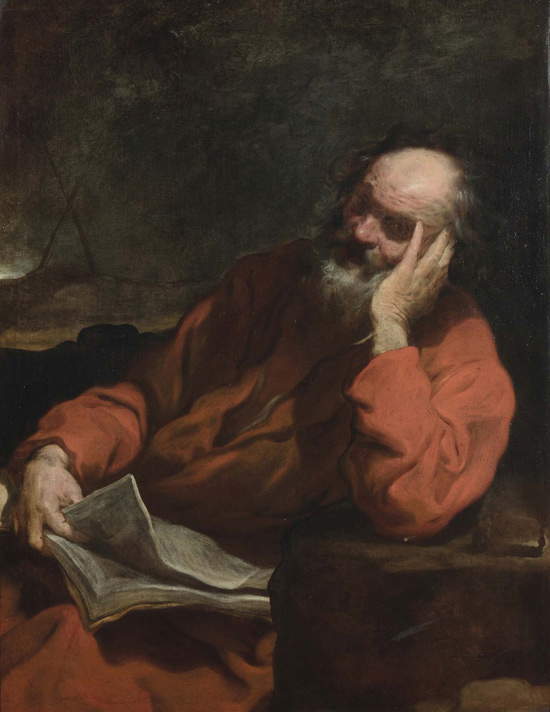

This is the case of two figures of saints, a St. Andrew and a St. Peter, datable to the second half of the 1730s: that is, following the return of Luciano Borzone from Rome, where the painter stayed between 1633 and 1635. The artist was in fact enrolled in the prestigious Academy of St. Luke, and according to the statutes in force at the time, in order to be considered an academician of St. Luke, it was necessary to be physically in Rome, and to have produced “laudable works in public.” we can therefore not only establish that Luciano Borzone had to be in the capital of the Papal States and that he produced a work there (which cannot be traced today), but we can also speculate that in those two years the Genoese artist had come into direct contact withCaravaggio’s art, given the turn to naturalism that Borzone’s painting experienced precisely in the mid-1930s. It is safe to assume that the two canvases were conceived and executed together, given their similar dimensions, and perhaps even for the same patron, who is unknown to this day: the earliest trace we have available dates back to December 27, 1657, when the inventory of the paintings of a Genoese patrician, Giovanni Francesco Bonfiglio, is drawn up. The document contains two notes telling us about “a painting named S. Andrea Apostolo, by the hand of Borsone. Lire 60” and “a painting named S. Pietro Apostolo, by the hand of Borsone. Lire 60.” However, the two notes, which include reference to the subjects of the paintings, the name of the author and the economic evaluation, are not sufficient to give us certainty that the two paintings mentioned are indeed the ones we are talking about: the hypothesis is, however, entirely plausible.

|

| Left: Luciano Borzone, Saint Andrew (c. 1635; oil on canvas, 127 x 100 cm; Private collection). Right: Luciano Borzone, Saint Peter (c. 1635; oil on canvas, 121 x 105 cm; Private collection) |

The pale Saint Andrew is depicted in a meditative attitude: his left hand holds up his head, the wrinkles of his frowning forehead and thoughtful gaze suggest all the concentration of the saint intent in his reflections on the book he has opened before him. In a remarkably realistic manner, the saint holds the index finger of his right hand between two pages so as not to miss the mark. We recognize that it is indeed St. Andrew because in the distance, in the background, we can make out the decussate cross, that is, the one that has the arms crossing diagonally, and which characterizes the saint to such an extent that it is also known as the “cross of St. Andrew.” The saint is depicted with the face and body of a person advanced in years: even the hands, wrinkled, stocky and with the skin bearing here and there a few spots, show the signs of age. The painting also shows us Luciano Borzone’s technique from this phase of his career: a technique that alternates dense, fast, and unfinished brushstrokes for the larger volumes (note the robe, but also the book: a white impasto furrowed by grayish veils is enough to suggest the idea of characters flowing on the sheets) with accurate strokes for certain details, for example to render the saint’s expression, or the flickers of light that linger on the curls of his beard and hair.

|

| Luciano Borzone’s Saint Andrew |

We find the same characteristics in Saint Peter, a painting in which Luciano Borzone’s naturalism reaches heights of touching intensity. The moment depicted by the painter in the scene is that immediately following the denial, that is, when the apostle, immediately after Jesus’ arrest, would deny three times that he had ever known him: And Peter remembered the words Jesus had said, "Before the rooster crows, you will deny me three times." And going out into the open air, he wept bitterly (Gospel of Matthew, 26:75). Luciano Borzone depicts an intimate moment of sincere repentance: Peter has his gaze stretched to heaven toward which he turns a melancholy and suffering expression, his eyes are swollen and shiny, his mouth is open to let out a faint lament of sadness and suffering, and a few tears furrow his grief-stricken face. His sentiment is true, sincere, deeply intense and human: Caravaggesque painting had brought the saints closer to the reality of the lower strata of the population, and Luciano Borzone’s painting also partakes of these innovations, depicting the two apostles as if they were two men, alive and real, gripped by real doubts, experiencing natural feelings. Their divinity becomes less and less immediate: even in Borzone’s St. Peter, as in the works of Caravaggio and the painters who referred to him, the main symbol of the sacredness of their figure, thehalo, is reduced to a barely recognizable mark, left with the tip of the brush above the figure’s head. All attention is devoted to states of mind: and only a painter with great skill and high sensitivity could succeed in giving the expression of a saint such dramatic pathos.

|

| Luciano Borzone’s Saint Peter |

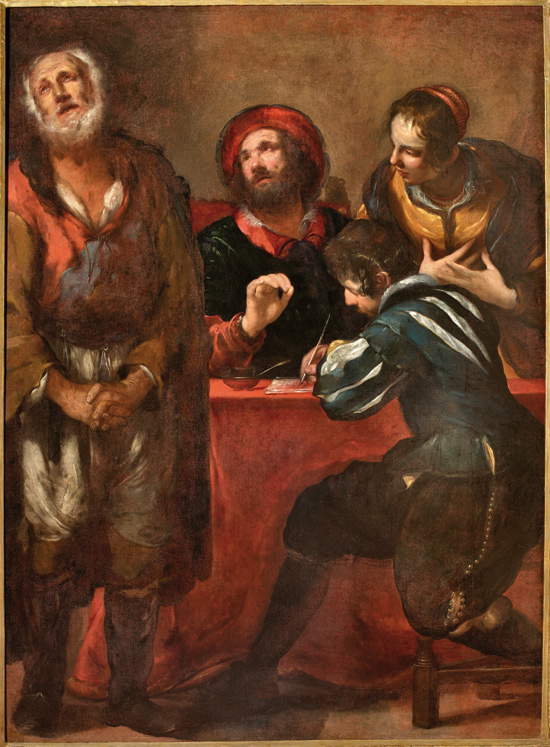

The figure of St. Peter is one of those that recur most in Luciano Borzone’s art, and the Genoese exhibition had the additional merit of exhibiting, among the paintings of the two saints, an additional painting from a private collection, which depicts precisely the moment of denial, with a closeness to the reality of the humble and a narrative taste that still refer, and perhaps even more immediately, to the art of Caravaggio: references that have, moreover, been noted by several art historians who have dealt with the painting, whose attributional story has been anything but simple (only in 1969 did Camillo Manzitti return the work to the Genoese painter).

|

| Luciano Borzone, Denial of St. Peter (ca. 1635; oil on canvas, 188 x 136 cm; Zerbone Collection) |

The subject is treated by Borzone as if it were a genre scene. Peter is on the left, and in his eyes we can already see his repentance: his gaze turned to heaven, his eyes shining, his hands clasped, and his mouth open show remarkable similarities to the painting in which the apostle is depicted alone. The woman we see on the left is the porter of the sanhedrin: she is mentioned in John’s Gospel (18:16-18) as the first person to ask Peter if he was not also one of Jesus’ disciples. The other two figures, on the other hand, we can assume are the Sanhedrin guards with whom, again according to John, Peter would stay, to warm himself, while Jesus was being questioned. In all the figures we find passages of intense realism. Of Peter we have already mentioned, but we could mention the gesture of the woman who, bringing her hands to her chest, seems almost to show all her curiosity, or again the guard who is writing, and the one who instead, with the gesture of his hand, seems almost to dictate something to his colleague or, as noted by Camillo Manzitti, to instruct him on how to draw up the document. The style is one that again alternates between volumes treated instead in a coarser way and details finished with meticulous care: the light, in particular, strikes the faces of the protagonists, making their moods even more evident.

It is curious to note that Luciano Borzone enjoyed a fair amount of fame when he was alive, and not only in Genoa, also due to the fact that, in addition to the paintings he made for private patrons, his fervent activity for public commissions is documented. It is curious because the echo of this fame has been almost completely lost, coming to us muted: and it has already been mentioned in the opening of what causes contributed to the forgetting of Luciano Borzone’s name by most art lovers. In recent times, however, the trend seems to have been reversed, and the Genoese exhibition, which follows an important monograph dedicated to the painter and also written by Anna Manzitti, would seem to take the shape of a further step on the path that should restore to the painter the consideration he deserves. For few painters in seventeenth-century Genoa could compete with Luciano Borzone in terms of flair, adherence to truth, intensity and humanity.

|

| Luciano Borzone’s three paintings compared at the exhibition Luciano Borzone. Vivid Painter in Early Seventeenth-Century Genoa (Genoa, Palazzo Nicolosio Lomellino, December 18, 2015 to February 28, 2016) |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.