In the first room one was greeted by a kind of large formless mass of many colors, with blacks and reds prevailing: an oppressive, distressing mass that occupied almost the entire room and forced visitors to remain almost glued to the walls. The room could not be crossed, because the bulky bulk of that sort of huge asteroid plunged from above prevented this: it was necessary to go around the intruder, to take it from one side, forced within an obligatory path because of its uncomfortable and claustrophobic presence. So began Tomorrow is another day, the exhibition that Mark Bradford (Los Angeles, 1961) mounted at the U.S. Pavilion as part of the 2017 Venice Biennale. The installation was called Spoiled foot, literally “twisted foot”: the reference is to the myth of the Greek god Hephaestus, thrown from the heights of Mount Olympus onto the earth, and thus expelled from the home of the gods, relegated to the margins, forced to live among mortals, in the earthly world, where he would later set up his own forge, teaching humanity arts and crafts and becoming the initiator of human civilization. That sort of pockmarked, repulsive surface is a strong, suffocating, powerfully communicative work. It is the emblem of the power that drove Hephaestus from Olympus, but it is also the emblem of contemporary power that relegates the last ones to the margins of society, locked within lives forced to follow precise, already established and defined paths. We felt the same sense of exclusion that Hephaestus felt when he was hurled down from Olympus, we felt the same sense of exclusion that the last ones feel every day, in every social context. We sensed the unease we feel when we realize that there is power looming over our lives.

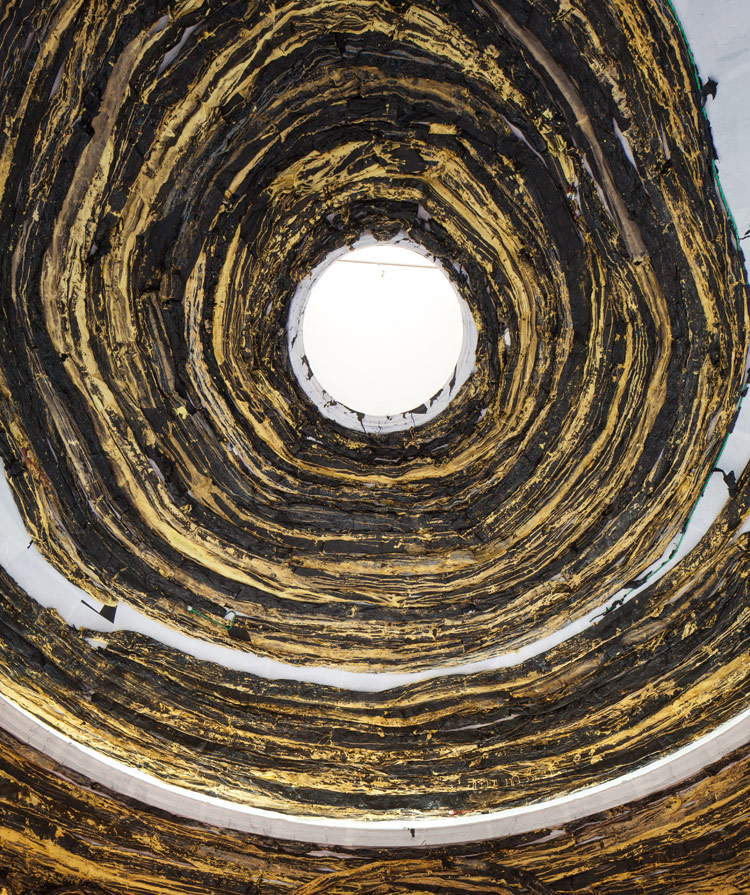

Yet, there seemed to be a thread of hope in all of this. When one arrived at the third hall, in the rotunda of the U.S. Pavilion, it was still alienating sensations that the audience continued to experience: one entered an environment that seemed almost assaulted by a kind of black and gold sludge, which had begun to affect the dome canopy and seemed to extend to the entire surroundings. It was an installation created from layers of glued and overlapping paper, following Mark Bradford’s typical modus operandi. For this work, the artist chose a lofty title: Oracle, or “oracle.” An oracle that warned us about the fate of our society, corroded by forces that aim to dismantle all the achievements we have made in recent years in terms of civil rights and social progress in order to set us back decades. Hope was represented by the light pouring down from above, theoculus letting the sun’s rays filter through: enlightenment is within our constant reach, aggression can never be totally accomplished. Tomorrow is another day, the title of the exhibition read, “tomorrow is another day.”

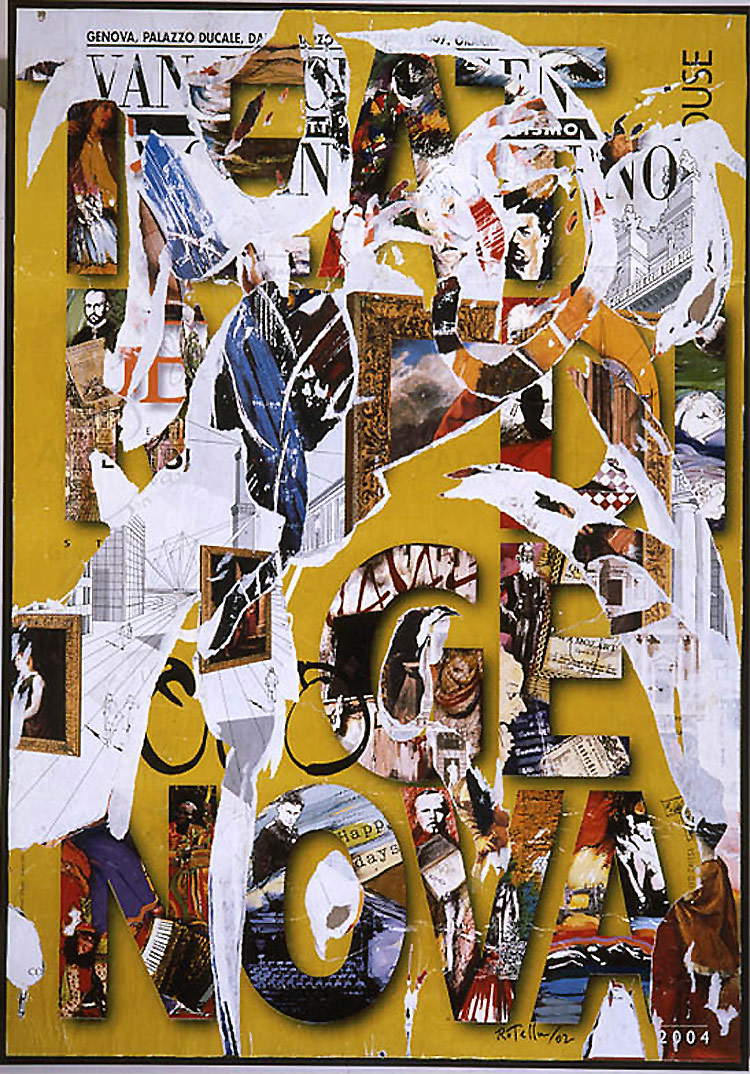

Bradford constantly confronts us with the problems of our time. In the introduction to the exhibition, it read that Tomorrow is another day is a story that tells us about ruin and violence but also about the capacity for action, opportunity, ambition, and belief in the ability of art to spur us into action. A story that Mark Bradford, ever since he was born, has lived (and continues to live) firsthand, in his own skin, he who as an African-American boy, bullied in school, homosexual, and devastated by the AIDS crisis era, had to struggle to emerge and become one of the world’s greatest contemporary artists. Even the very technique he uses is a reference to the context in which the artist was born and raised. Bradford began creating artworks using torn posters found on the streets of Los Angeles, often glued on top of each other: a necessity, since it was a cheap and abundant material, and the artist, at the beginning of his career, could not afford expensive pigments or materials. Inspiration had come from the work of other artists who, already in the 1960s, created works with poster cutouts: Mimmo Rotella, Jacques Villeglé, Raymond Hains. The end result isabstract art, but it is never completely abstract. Bradford calls it “social abstraction”: that is, an abstraction that fits within a specific social or political context.

|

| Mark Bradford, Spoiled foot (2017; mixed media; ph. credit Francesco Galli. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia) |

|

| Mark Bradford, Oracle (2017; mixed media; ph. credit Francesco Galli. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia) |

|

| Mark Bradford, Oracle, detail of the dome (2017; mixed media; ph. credit Francesco Galli. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia) |

|

| Mimmo Rotella, Homage to Genoa (2002; décollage, 100 x 70 cm; Genoa, Museo di Villa Croce) |

|

| Raymond Hains, Untitled (1959; torn posters on iron, 200 x 200 cm; Madrid, Museo Reina Sofía) |

This is what has been happening since his earliest works, such as Scorched Earth (“scorched earth”), made in 2006. A large painting measuring two and a half by three meters, with rectangles of colored paper arranged following different directions, above a white base on the horizontal lines, black on the diagonal ones and red in the background. It is a work inspired by a historical event that took place in 1921 in the Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa, Oklahoma’s second largest city: it happened at the time that a nineteen-year-old black boy was suspected of abusing a white girl, and was taken to the local police station. Local newspapers, on the evening of the event, wondered about the possibility of the “Negro” being lynched by the mob. Indeed, the next day, a crowd of whites, animated by less than positive intentions, gathered outside the police station. The African American community, fearing for the fate of the boy, accused without evidence and in danger of being lynched, offered its help to the police in order to keep the mob at bay. However, the situation degenerated: whites and blacks came into contact, a gunshot was heard, and as a result an initial shootout ensued. It was the fuse that set off the riot: the whites, armed, enraged and outnumbered, began to hunt down the blacks and took to setting fires in the streets of Greenwood, targeting the properties of the black community, which were destroyed and looted, as well as the defenseless bystanders against whom, without any scruples, shots were fired. The local police were insufficient to stop the riot, and it became necessary for the Oklahoma National Guard to intervene, arriving directly from the capital Oklahoma City. The exact number of casualties has never been known: estimates vary from 36 deaths recorded by state authorities (including 26 blacks and 10 whites) to more than 300 estimated by the American Red Cross. Regardless, the Tulsa race riots still represent one of the most serious incidents of racism in American history.

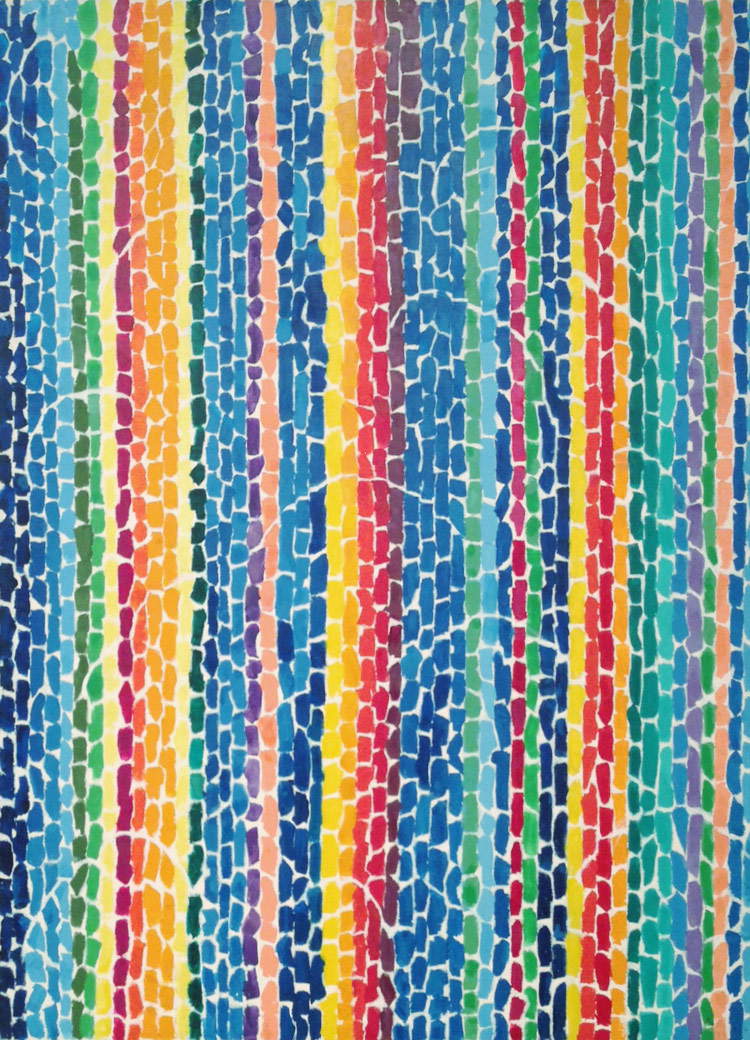

Mark Bradford’s work is a kind of bird’s-eye view of Greenwood convulsed by the riots. One can see the streets, the blocks, one almost seems to see, to the right, at the most disordered point of the composition, the areas most affected by the devastation, and if one compares the painting with period photographs, with the columns of smoke rising from the homes, factories and stores destroyed by the fires, one is amazed to see the vivid similarities. However, there are no direct references to the tragedy, nor to the place where it occurred. Scorched Earth thus becomes a universal message, the value of which becomes immediately clear when one considers that the work was made at the time when the war in Iraq was raging. “Technically,” wrote critic Holland Cotter at an exhibition where the painting was shown,"Scorched Earth is abstract art. There is nothing to identify the historical event in the work. But everything tells us about cities, about violence, about fires.“ And this is true of virtually all of Bradford’s works. ”Apparently,“ Cotter wrote again in 2010 speaking of the artist’s most recent creations, ”they have no narrative implication. It seems that all their interest lies in the material appeal of their surfaces, which present, alternately, pieces with raised portions and parts that are instead as smooth as silk. Of course, ’pure’ abstraction in itself has a narrative, which tells us about how and why certain stylistic choices were made, and Mark Bradford is fully aware of this.“ Not only that, Mark Bradford’s art fits into the groove of a tradition, typically African American (Cotter brought the examples of Alma W. Thomas, Jack Whitten, William T. Williams and others), which has always sought to avoid works with an excessively didactic flavor, but which were at the same time capable of ”incorporating lives and stories into abstraction, often in a symbolic way."

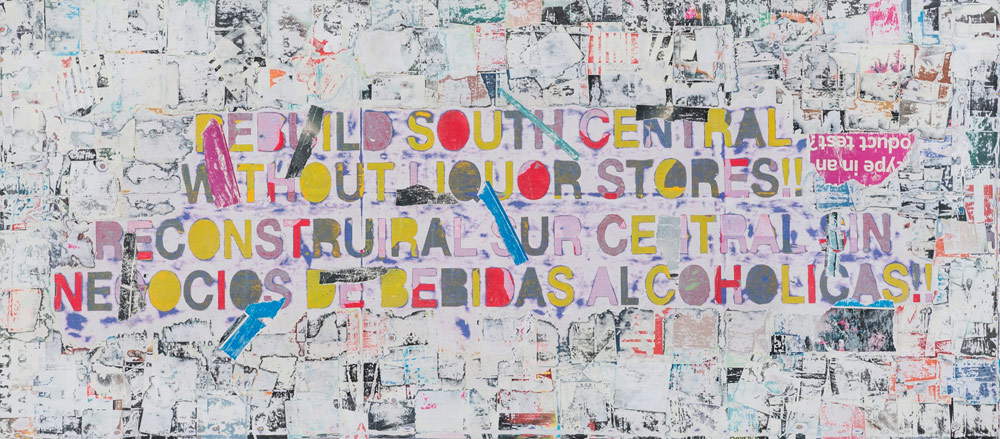

Scorched Earth, precisely because of its value, had ended up giving the title to Mark Bradford’s first solo exhibition held in a hometown museum: it was 2015 and the venue was theHammer Museum in Los Angeles. “Scorched Earth” thus became a kind of synonym for the most disturbing aspects of contemporary Western society, and the exhibition intended to examine some of them, with particular reference to the artist’s own experience. Here, then, is Finding Barry, the work created especially for the hall: a large map of the United States showing, for each of the federation’s member states, the number of inhabitants (per hundred thousand) diagnosed with AIDS in 2009. The trembling edges and areas where the artist deliberately allowed glimpses of the murals that decorated the wall prior to his intervention (one of which was the work of Barry McGee: hence the title of Bradford’s painting) can be read in reference to the changing view of the issue over time and the perspective the public takes on it over the years. “I wanted to dig until I found Barry, the first one to decorate the wall,” Mark Bradford himself said in aninterview in which he was specifically asked about Finding Barry. “It was almost like finding the first person who contracted HIV, or something like that. I wanted people to see the numbers and understand that AIDS is a real thing, that it affects real human beings. I wanted people to wonder why the numbers were higher in certain areas than in others. AIDS affects mostly where there are black people and homosexual men. I think people forget how much devastation AIDS has caused, and in some ways is still causing. But we will never know what its impact has really been, and consequently how great the shame this brings.” The review then offered much more food for thought. Dead hummingbird showed visitors the silhouette of a dead hummingbird, as per the title of the work, a metaphor for the suffering of the body, but probably also for how helpless the sick are in the face of a society guilty of leaving them alone. A series of untitled works seemed to want to enter the blood of the sick to see how the cells were being affected by the virus. And again, Circa 1992 harkens us back to the riots of the 1990s: the phrase we read in the work, Rebuild South Central Without Liquor Stores, is taken from a sign that activists in a Los Angeles parish community displayed during the 1992 Los Angeles Rio ts, a series of riots that erupted following the acquittal of four white police officers who had beaten an African-American taxi driver to a pulp. The five days of violence unleashed by the black community, which lashed out at innocent whites and Asians, claimed fifty-four lives. A sign, a call to rebuild, a reminder of the past.

|

| Mark Bradford, Scorched Earth (2006; posters, photomechanical reproductions, acrylic gel, carbon paper, acrylic paint, bleach, and mixed media on canvas, 241.94 x 300.36 cm; Los Angeles, The Broad Museum) |

|

| Alma W. Thomas, Sunshine and Flowers (1968; acrylic on canvas, 182.2 x 131.8 cm; New York, Brooklyn Museum) |

|

| Mark Bradford, Finding Barry (2015; wall painting; ph. Credit Joshua White; Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth) |

|

| Mark Bradford, Dead hummingbird (2015; mixed media, 214 x 275.6 cm; Los Angeles, Hammer Museum; Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth) |

|

| Mark Bradford, Circa 1992 (2015; mixed media on panel, 124.5 x 520.7 cm; Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth) |

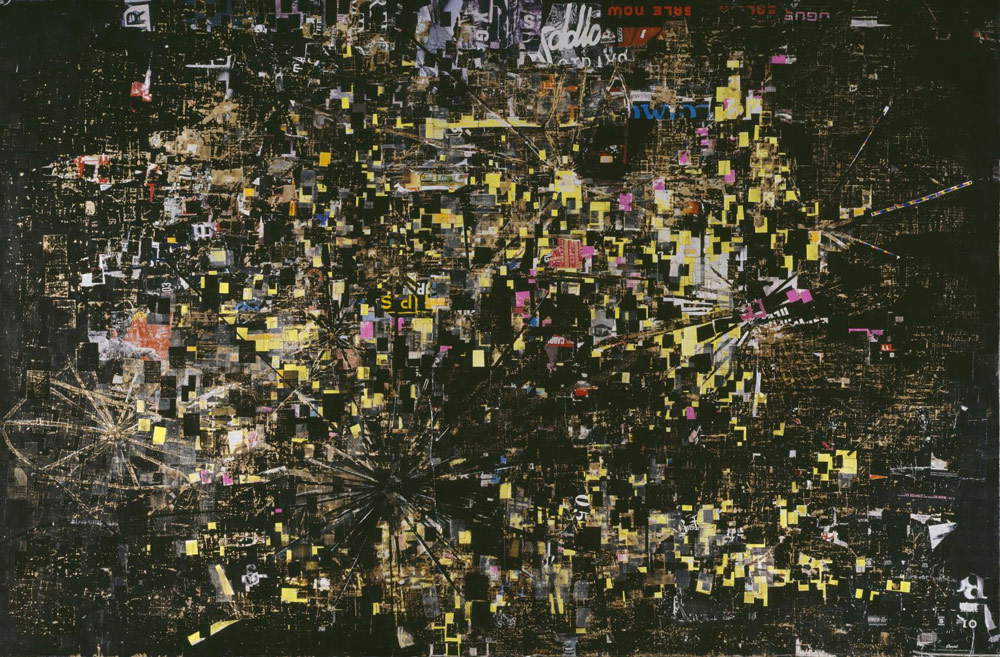

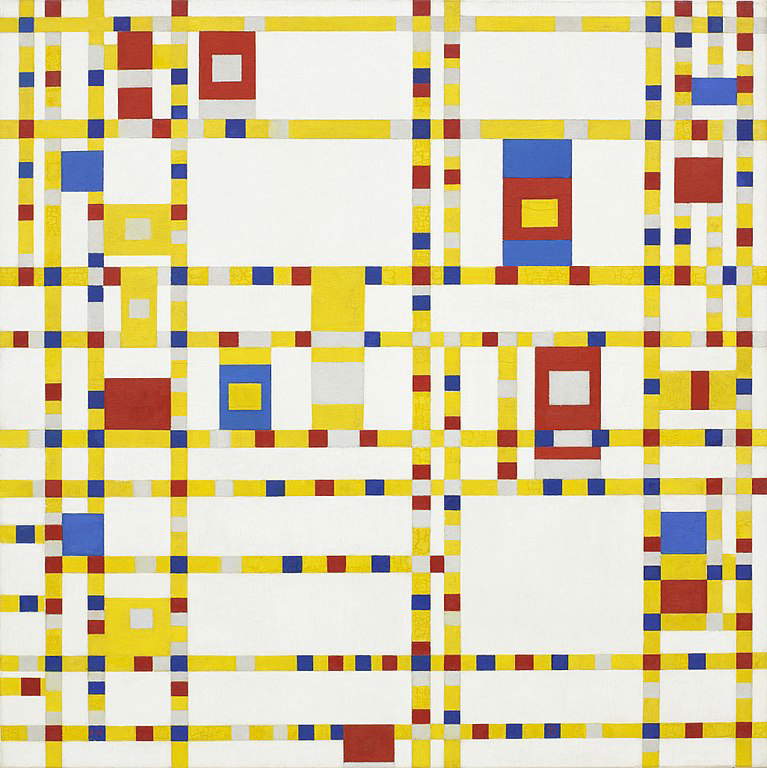

That there is much autobiography in Mark Bradford’s work is particularly evident, and it is a constant in his artistic output. In 2002 he participated in Art Basel Miami with an installation, Foxyé Hair, which reconstructed his mother’s store, who was a hairdresser: he, too, had been a hairdresser before his artistic career, helping his mother in her store, which was called Foxyé Hair. Art Basel audiences could also have their hairstyles fixed by the artist. Of course, since then the artist’s language has changed and matured considerably, but this component, strongly linked to his own roots (cultural, familial, territorial) has never left his works. Take, for example, Los Moscos, a work from 2004, which was presented two years later at the Liverpool Biennial, and in 2012 became part of the collection of the Tate Modern in London: it is a kind of view of a U.S. metropolis, with its skyscrapers, signs, neon lights, and streets. Further evidence of the interest in topography that would seem to animate much of his output. But the city, in Bradford, really enters the painting, since the work is constructed from waste materials: those that the artist collected and gathers along the streets. “Moscos” (“mosquitoes”) is the term with which, in California slang, Hispanic migrants working in the urban areas of Los Angeles and San Francisco are identified: the work thus establishes a kind of contrast between the California of the collective imagination, the one linked to entertainment, movies, beaches, and glam, and the one of the humble people that is barely spoken of. As a result, the mosaic Bradford composed ( neo-plastic memories surface: think of Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie-Woogie ) puts together a heterogeneous image of the city: the various layers of paper of which it is composed communicate with one another, intersect, form relationships, a metaphor for the relationships and exchanges that occur daily in the U.S. metropolis.

“I use paper,” Mark Bradford said in another interview, “because it’s a container of information, because it has a memory, it’s an unforgiving material, and it has to do with fatigue.” Memory is another crucial aspect of his work, which is often confronted with history. “I have always been strongly interested in exploration. I would have liked to have been an explorer or an archaeologist. I traveled a lot, I traveled through Europe in the 1980s, I went everywhere. I love civilizations and the marks they left behind. I love visiting ruins, when you dig you end up finding another culture at the bottom of them, and again another culture even deeper. I have always been attracted to cultural memory. I like to dig into memory. I have always liked cities and urban myths. My favorite activity is walking the streets, on any street, in the middle of the night, always in the middle of the night.”

Several of Mark Bradford’s works have become part of the collections of major world museums in recent years. At New York’s MoMA, the public can view Let ’s walk into the middle of the ocean (“Let’s walk in the middle of the ocean”), from 2015, with the blue expanse of the ocean becoming a metaphor for a city in the grip of social strife and claims. The Centre Pompidou in Paris, on the other hand, has Spider feet (“Spider feet”), from 2012, a work directly inspired by French history since, the museum’s official presentation states, it depicts Napoleon’s territorial conquests, using the colors of maps of the time. In Italy, it is possible to observe one of Bradford’s works at MAXXI in Rome: titled Dive into criticism, it dates back to 2014 (the same year it became part of the Roman museum’s collection, thanks to a donation from Pilar Crespi and Stephen Robert) and is another metaphor of a contemporary urban context against which, as the work’s title suggests, Mark Bradford directs his criticism.

|

| Mark Bradford, Los Moscos (2004; mixed media on canvas, 317.5 x 483.9 cm; London, Tate Modern) |

|

| Piet Mondrian, Broadway Boogie-Woogie (1942-1943; oil on canvas, 127 x 127 cm; New York, MoMA) |

|

| Mark Bradford, Let’s walk to the middle of the ocean (2015; paper, acrylic paint and lacquer on canvas, 259.1 x 365.8 cm; New York, MoMA) |

|

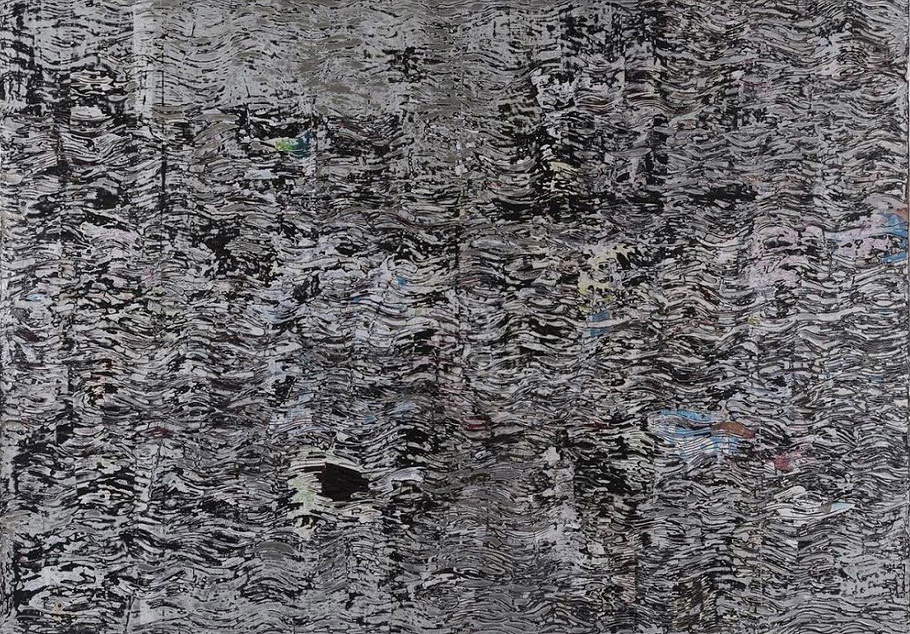

| Mark Bradford, Spider feet, detail (2012; collage-décollage on canvas, 259.1 x 365.8 cm; Paris, Centre Pompidou) |

|

| Mark Bradford, Dive into criticism (2014; mixed media on canvas, 259 x 365.8 cm; Rome, MAXXI - Museo Nazionale delle Arti del XXI Secolo) |

Mark Bradford’s is an art that has been able to capture diverse inspirations: from the Impressionists to Mondrian, from the Affichistes to nineteenth-century history painting, from African American art to Malevič (the latter often referred to as one of the Californian artist’s main points of reference). And of course, important was the lesson of American Abstract Expressionism, of which Bradford is now considered the main continuator. A kind of new Jackson Pollock, as ArtNet News editor Andrew Goldstein called him in an article commenting on the 2017 Venice Biennale exhibition. And not so much for stylistic or technical reasons as for the scope of his art: “we can say that Bradford is our Jackson Pollock. Not only because of his well-known technique of street posters that echo Pollock’s invention, dripping. Pollock’s real, revolutionary contribution was to bring a particular endeavor, namely the whole, theatrical performance of action, into painting, expanding the definition of the medium in a way that has influenced an innumerable array of artists. Bradford is doing the same: he is expanding painting by bringing social practice into the artist’s studio and tying his work as a painter to his work with foster children and other at-risk communities.”

Indeed, in a manner entirely consistent with the message of his art, Mark Bradford carries out several social projects. In Italy, too: in 2017, in Venice, the artist announced his support, for six years, for the Rio Terà dei Pensieri cooperative, to open a store where inmates and detainees from the Venetian prison of Santa Maria Maggiore will sell their products. The most challenging project, however, is the one Mark Bradford has set up in his home country: in 2014, the artist founded the Art + Practice foundation in Los Angeles, along with collector Eileen Harris and activist Allan DiCastro, which aims to “encourage education and culture by offering services to foster children living mostly in South Los Angeles.” The foundation operates in the Leimert Park neighborhood, is headquartered on a two-thousand-square-foot campus, and offers a wide range of activities: the A+P program includes meetings and lectures on art, performances, exhibitions-all open to the public. To the young people in its care, the foundation also offers training courses, housing opportunities, individual support for education and employment. “Often culture,” said Mark Bradford, “gets caught up in a static, traditional narrative. Contemporary ideas, on the other hand, offer culture the elasticity and flexibility that is always a breath of fresh air. However, these ideas should not be the exclusive preserve of those who can afford to enter a museum or symposium in the ’good living room of the city.’ [...] Often, people in black communities do not have access to healthy food. The same is true with access to contemporary ideas, with access to better quality health care, with access to better schools. Do you know how things would change if little Barry or little Mark could walk inside a contemporary art space based in their neighborhood?”

Mark Bradford was born in 1961 in Los Angeles, where he lives and works. Approaching art practice in his early thirties, he graduated from the California Institute of Arts in 1997. His major solo exhibitions were held at the Whitney Museum in New York in 2007 (“Neither New Nor Correct”), the Cincinnati Art Museum in 2008 (“Maps and Manifests”), the Aspen Art Museum in 2011, the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles in 2015 (“Scorched Earth”), the Venice Biennale in 2017 (“Tomorrow is Another Day”) and, also in 2017, the Smithsonian in Washington (“Pickett’s Charge”). He has also exhibited at the Instabul Biennial in 2011, the Seoul Biennial in 2010, the São Paulo Biennial in 2006, and the 2006 Whitney Biennial. In 2014 he received the United States Medal of Arts.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.