May 21, 1972, Pentecost Sunday, about 11:30 a.m., St. Peter’s Basilica. A man with long hair and a slight blond beard, dressed in a blue suit, a light red shirt and a bow tie, enters the greatest temple in Christendom. All of a sudden he climbs over the balustrade placed in front of Michelangelo’s Pieta, pulls a geologist’s hammer from his jacket, and begins to repeatedly strike the Madonna and Christ several times. It later turns out that the young man is a Hungarian geologist, László Tóth (Pilisvörösvár, 1938 Strathfield, 2012): he is thirty-three years old, the same age Christ was when he was nailed to the cross. In 1965, at the age of twenty-five, Tóth had moved to Australia, where, however, his degree in geology was not recognized, and he therefore found work as a laborer in a soap factory. Not much else is known about his life before the act: we only know that in 1967 he had been involved in a fight with some of his compatriots in Australia, and that he had disappeared for some time before reappearing again in Europe.

It was 1971: László Tóth had moved to Italy, and settled in Rome, with a physical appearance intended to recall that of Christ: long blond hair, and the same well-groomed stubble he wore at the time of the attack on the Pieta. At the time of his arrival in Rome he could not slur a half-word of Italian, but he did not care: he would later explain to his lawyer that his goal was to be recognized as the new messiah. Although those who knew him during his time in Rome testified that they found no oddities in his behavior. The art historian Dario Gamboni, who in a book on the history oficonoclasm (The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism Since the French Revolution) has reconstructed the affair in great detail, recounts that Tóth had sent several letters to Pope Paul VI asking him for a meeting at Castelgandolfo. Which, of course, he would never have, since the pontiff did not respond to his letters. And so, for Tóth the idea that the Church admits only a dead Christ becomes unacceptable.

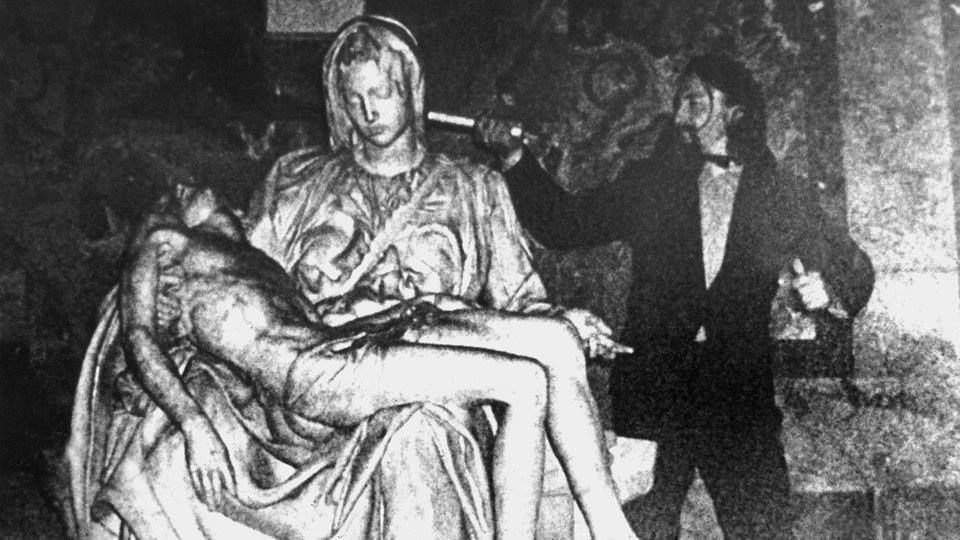

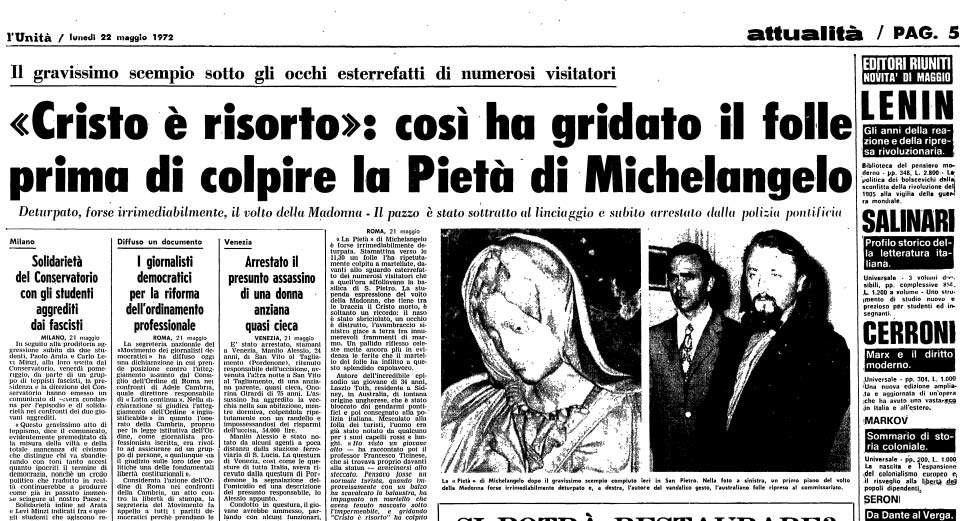

And here then is the planning of the gesture, which must be accomplished within a short time, because on July 1, 1972, Tóth will celebrate his 34th birthday, and the anniversary will nullify the symbolic significance of the action. As he strikes the Pieta, the Hungarian continues to repeat in Italian, “Christ is risen! I am Christ!” The action lasts at least a couple of minutes: a young firefighter, 20-year-old Marco Ottaggio, eventually manages to get the better of Tóth (ten days later he will be awarded by Paul IV the cross of knight of the pontifical order of St. Gregory the Great for his deed), aided by other security guards who were in the basilica at the time, and the Hungarian iconoclast is dragged away from St. Peter’s, partly to avoid the wrath of the crowd that, amid disbelief, fear (with even a few episodes of panic) and anger, had witnessed the gesture. Those who engage in a scuffle with Tóth to prevent him from doing further damage include, according to some accounts, the U.S. sculptor Bob Cassilly, who is there at the time and who strikes Tóth forcefully to make him desist from his plan. Paul VI is informed of the incident in the early afternoon: the pontiff wonders why “this act against a heritage that belongs to all humanity,” asks to be escorted in front of the mutilated work, and lingers for at least a quarter of an hour in front of the Pieta, gathering himself in prayer. Tóth succeeded, with twelve hammers given vertically, in severing the Virgin’s right hand cleanly, detaching her nose, and leaving marks on her face, eye, and veil: a hundred fragments will be counted at the end.

The man had turned on the very figure of Our Lady: probably because he saw in her the symbol of the Church. And during the interrogations, Tóth keeps talking about himself as if he were Christ. He goes on to repeat that he personally chose Michelangelo to sculpt the Pieta (“his hands were guided by me,” he tells the investigators, and also on the basis of this assumption, that is, believing that he was the inspiration for the masterpiece, he claims to be able to dispose of the work as he pleased). And as soon as he was arrested he apparently said that his desire was to destroy all simulacra of Christ, because he is the reincarnated Christ. In the following weeks, Tóth also sent a letter to the newspapers, in which he explained in his own way the reasons for the act: “Now that everyone thinks I am crazy my time has come and I will say who I am. I am the one who knows the truth, I am Christ. I am the one who prayed and sang in the churches. I do not say I am Christ, God says so, and this is his word: My son, Christ, you must destroy and build and teach because I am you. That I am Christ is no secret, if no one has known it until now know it now. The Pieta statue is a divine work, I made it and I can destroy it. I fulfilled Christ’s mission on earth, then I chose a pure and gentle young man to make a statue. So it is I who created this beautiful, unique and divine statue. The name of Michelangelo Buonarroti is prophetic because it is that of Michael the Archangel, the head of all angels; and Buonarroti means it is good to be broken; in fact what I have accomplished is a punishment from God and it is willed by him.”

One of the greatest sculptors of the time, Giacomo Manzù, who is reached by the newspaper L’Unità for comment, also spoke out on the affair. “It is the greatest disgrace against civilization and against culture,” says the great artist. “I never thought that madness or insanity could disfigure, if not completely destroy, one of the most significant masterpieces of man. A restoration I believe is an almost impossible task, I am willing to try.” In the end, however, the undertaking to restore the work will succeed: the intervention takes place directly in St. Peter’s, and the parts detached from Tóth are precisely reintegrated thanks in part to casts of the Pieta. For the tiny fragments that cannot be reattached to the work, reparations are made from Carrara marble dust mixed with glue. The restoration is being directed by Brazilian art historian Deoclecio Redig de Campos, who was director general of the Vatican Museums since 1971, and carried out by Vittorio Federici, Ulderico Grispigni, Giuseppe Morresi and Francesco Dati, the most experienced restorers in the Vatican laboratories.

The work, which was also followed with great interest by one of the greatest restorers in history, Cesare Brandi, then director of the Central Institute for Restoration, lasted nine months and, as anticipated, was carried out directly in the chapel of the Pieta in St. Peter’s: a wooden bulkhead protected the restoration site from the view of observers, as well as from the possible gestures of other ill-intentioned people. Instead, tests on adhesives and material analysis are carried out in the laboratory. The tests end on October 7, the date when the operational phase begins. The left eye, which was heavily damaged (László Tóth’s hammer had not only chipped it, but had also left a trace of blue paint, an oily substance), is reconstructed with the help of a silicone cast, and the stain is removed with the help of adhesive tapes, rather than being scraped away, at the risk of leaving obvious shading. The fragments of the nose are then reattached, and last the forearm is put back in place with a stainless steel pin. Finally, a cleaning is carried out. Not all the gaps are restored: some are deliberately left unresolved behind the back of the neck, as an imperishable reminder of the thoughtless act. The work is finally returned to the world on March 25, 1973. Brandi reserved words of praise for the intervention: “The kind of restoration that has been [...] carried out, and one must be grateful for it,” he would write in Corriere della Sera, “is a prudent, respectful and removable restoration. Above all, I appreciate the fact that even the very small additions that have been made to the offended eyelid and the sides of the nose, which was suddenly detached, are in an easily removable synthetic material, as is also the mastic with which the tip of the nose was attached and the reconstituted parts of fragments of the veil.”

In the end, Tóth would suffer no indictment: on January 29, 1973, he was admitted to a psychiatric hospital, from which he was released on January 9, 1975, only to be taken to Australia. Even in his adopted country he is not arrested. We do not know then what happened to Tóth in the following years: he apparently spent the last years of his existence in a nursing home in Strathfield, where he died on September 11, 2012. However, his story has been a source of inspiration for writers and musicians. Actor, screenwriter and author Don Novello, for some time, took to writing a number of letters to famous people using the Hungarian’s first and last name as a pseudonym: the letters would later be collected in several volumes. Cartoonist Steve Ditko would publish a book in 1992 called Laszlo’s Hammer, an essay on the opposition between creation and destruction written in the form of a comic strip. And the debut album by singer and guitarist Giorgio Canali, Che fine ha fatto Lazlotòz (1998), also refers to László Tóth, where, in the song that gives the record its name, Canali imagines a God in his daily routine wondering, precisely, what happened to László Tóth, whose gesture is somehow compared to the iconoclasm of punk music.

László Tóth’s attack on the Pieta, after triggering an intense debate on the protection of works of art, has produced an effect that is still visible today: for fifty years, Michelangelo’s work has been protected by thick bulletproof glass, intended to prevent the replication of a gesture similar to that of the Hungarian who believed he was Christ. But that does not prevent one from marveling at Michelangelo’s masterpiece.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.