by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta, published on 15/03/2020

Categories:

Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

Is there only one Mona Lisa, the one by Leonardo da Vinci in the Louvre? Actually there are dozens of copies and variations of it all over the world, although none is by the great genius. Let's look at the most interesting ones.

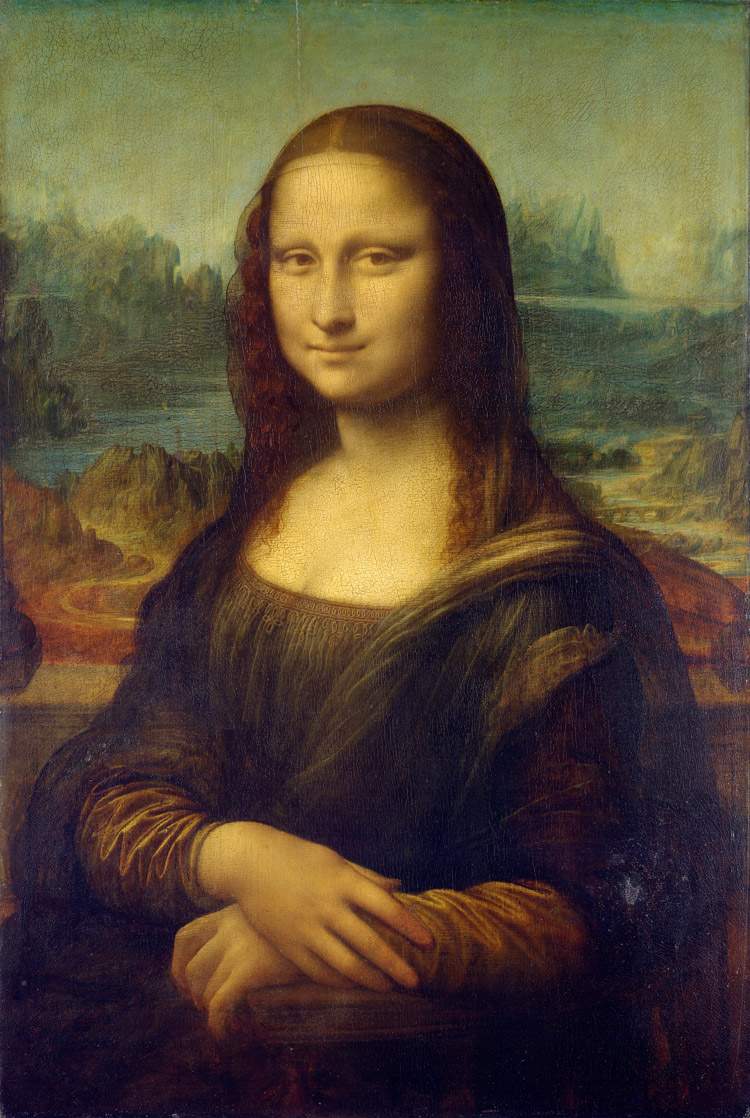

What art lover has never harbored, even in secret, the dream of seeing the Mona Lisa again, even temporarily, in Italy? Of course, we know that it will be very difficult, if not impossible, to see the celebrated painting by Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519) again in our parts: the work is, first of all, extremely delicate, and then it is inextricably associated with the museum that houses it, the Louvre, and being the masterpiece that all visitors to the French institution expect to see when they visit it, it will be very unlikely to be loaned out. The last “release” of the Mona Lisa was in 1974, when it was first exhibited in Tokyo (amidst a thousand protests from those who did not want the work to leave, and indeed it was not an easy move: the work, in fact, was the subject of an attack by an activist who, in protest against the absence of access for the disabled to the National Museum of Tokyo, where the Mona Lisa was on display, daubed the work with red spray paint on April 20 of that year, the day of the opening of the exhibition that displayed it), and then in Moscow. The director of the Louvre, Jean-Luc Martinez, later reiterated the point at the celebration of the five-hundredth anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci’s death: the Mona Lisa is too fragile to face travel, and moving it could cause irreparable damage. To paraphrase, we can take that as a definitive “no.”

Museums around the world, therefore, have to make do, but there are those who can do it better than others, because the fortune of the Mona Lisa, even in ancient times, was such that today, scattered in every corner of the globe, there are dozens of copies and ancient variants of it, some even of high quality: the very five-hundredth anniversary of Leonardo’s death has given rise to a renewed interest in this long list of “younger sisters” of the very famous Mona Lisa, some of which are also present in Italy. The worldwide fame of the Mona Lisa was born only in the 20th century, but already in Leonardo’s time his portrait of Lisa Gherardini (Florence, 1479 - Florence, 1542), also called Lisa del Giocondo after her husband Francesco di Bartolomeo di Zanobi del Giocondo (Florence, 1465 - 1542), who commissioned the work, enjoyed a certain amount of success. Already the artist and historiographer Giorgio Vasari (Arezzo, 1511 - Florence, 1574) listed the qualities of the Mona Lisa: “took Lionardo to do for Francesco del Giocondo,” we read in the 1550 Torrentine edition of the Lives, “the portrait of Mona Lisa his wife; et quattro anni penatovi lo lasciò imperfetto, la quale opera oggi è appresso il re Francesco di Francia in Fontanableo. In whose head those who wished to see how far art could imitate nature, could easily understand it, because there were contracted all the minutiae that can be painted with subtlety. [...] Et nel vero si può dire che questa fussi dipinta d’una maniera da fa tremmare et temere ogni gagliardo artefice, et sia qual si vuole. [...] And in this of Lionardo there was a grin so pleasant that it was a thing more divine than human to see it, and it was held to be a marvelous thing, not to be the living otherwise.” Vasari’s description (who, for the record, had a strong admiration for Leonardo, almost bordering on worship) also lingers on many of the painting’s details, and since the great Aretine’s judgment was held in high esteem among many of his contemporaries, we can attribute part of the Mona Lisa’s success (at least in ancient times) to him. But, at about the same time, contrary opinions were also recorded: lapidary was the comment of Federico Zuccari, who, having seen the work in France, at Fontainebleau, in 1574, called it “secha e di poco gusto e da fugirla e non dar fine mai a cosa alcuna come fece il ditto Lionardo che consumò la vita in sustanzie di parole e ghiribizzi sufistichi di poco utilità a se stesso e al arte.”

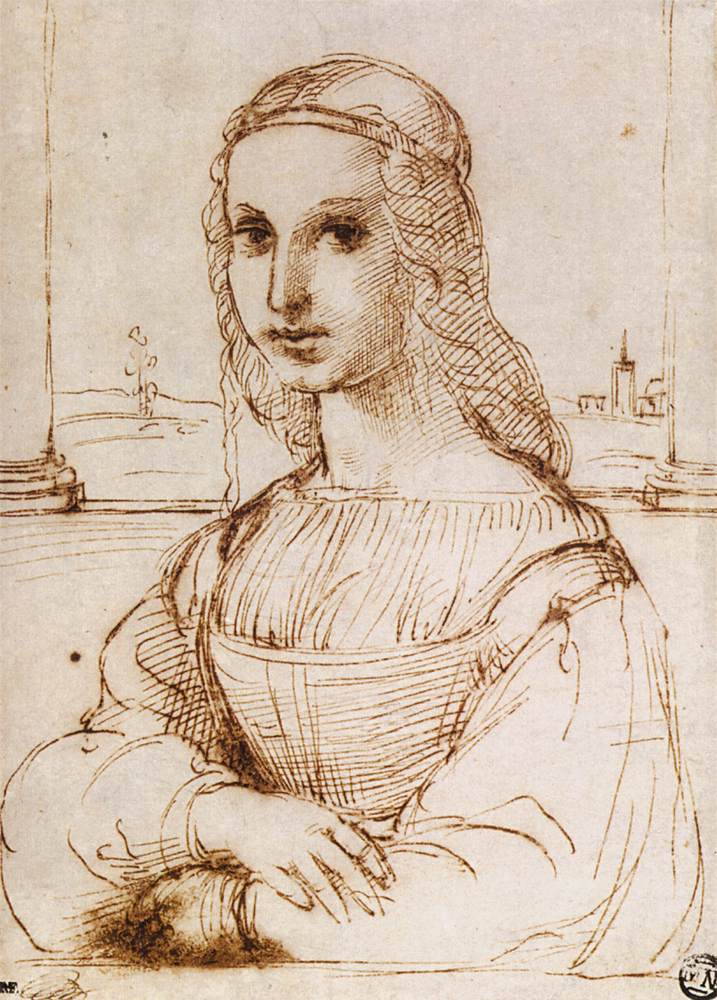

Adding to the work’s fame, therefore, were the opinions of the great artists who saw it, but we have to imagine that the echoes of the Mona Lisa must have begun to be heard much earlier, perhaps even at the same time as it was made (the early sixteenth century: the Louvre sets a date roughly between 1503 and 1506). The first artist to be fascinated by the Mona Lisa was one of the greatest, Raphael Sanzio (Urbino, 1483 - Rome, 1520), who was also strongly attracted to the works of Leonardo da Vinci, and Vasari himself attests to this: the historiographer lets us know, in fact, that the Urbino measured himself against Leonardo’s works, “but for diligence or study that he made, in some difficulties he could never pass Lionardo, and although it seems to many that he passed him in sweetness and in a certain natural ease, he nevertheless was not point superior to him in a certain terrible foundation of concepts and greatness of art.” Many have noted how a drawing by Raphael now in the Louvre, a sketch for a female portrait (Roberto Longhi associated it with the Lady with the Unicorn now in the Galleria Borghese, separating it instead from the Portrait of Maddalena Strozzi in the Uffizi to which other art historians before him had approached it instead), is based directly on the Mona Lisa, from which it derives the idea of the hand grasping the wrist, the slight twisting of the neck, the layout with the backdrop, the gaze. And indeed, it is likely that Raphael was trying to learn from Leonardo the study of expression, the posture of the hands, the ability to communicate a feeling through an attitude, and consequently the full potential of movement. We do not have certainty that Raphael was directly inspired by the Mona Lisa, but the similarities are obvious and there should not be much doubt about it.

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, The Mona Lisa (1503-1506; oil on panel, 77 x 53 cm; Paris, Louvre) |

|

| Raphael, Female Portrait (c. 1505-1507; pen, brown ink and traces of black chalk on paper, 222 x 159 mm; Paris, Louvre, Département des Arts Graphiques) |

|

| Raphael, Lady with the Unicorn (c. 1505-1507; oil on panel, 65 x 51 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

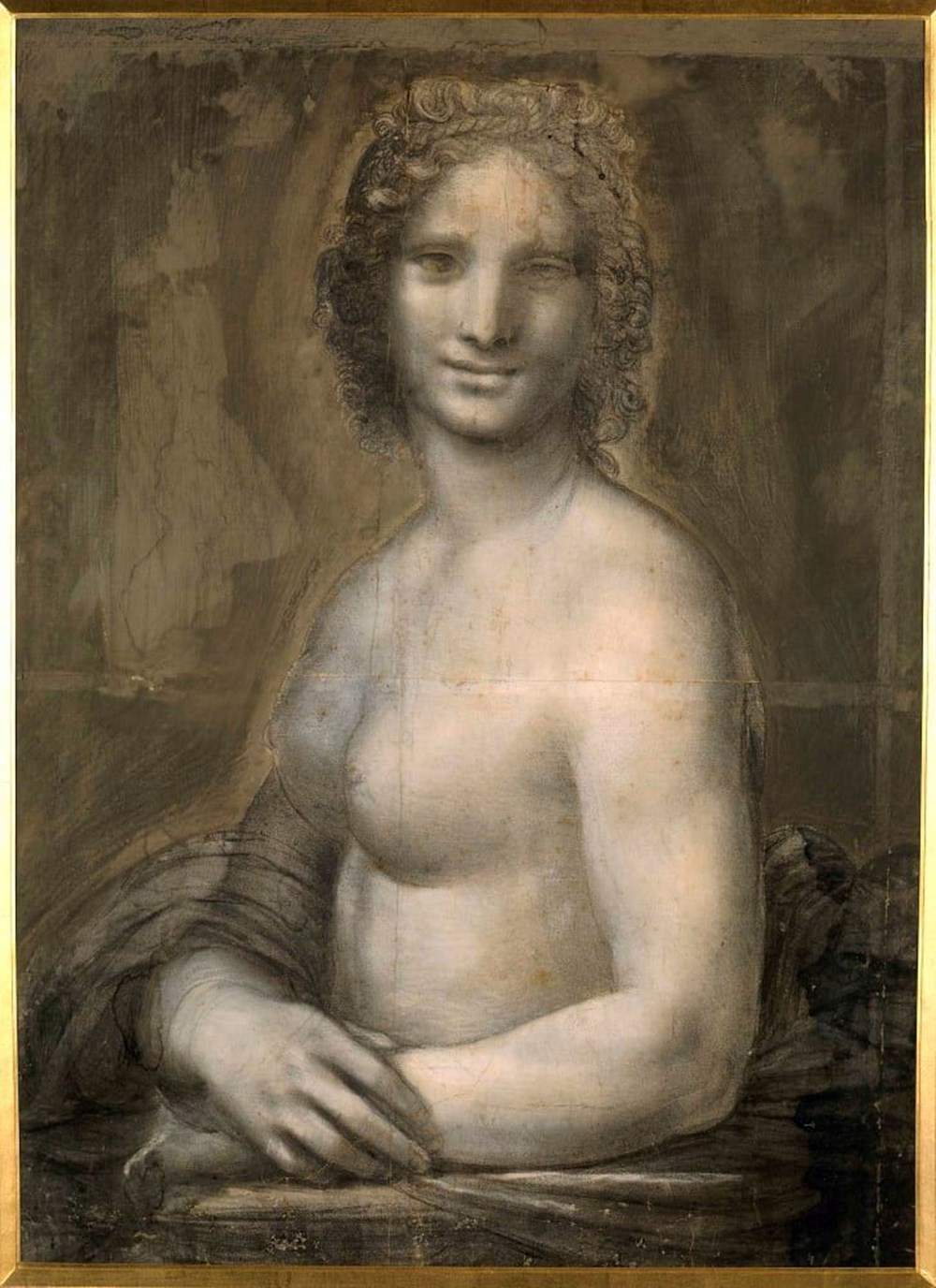

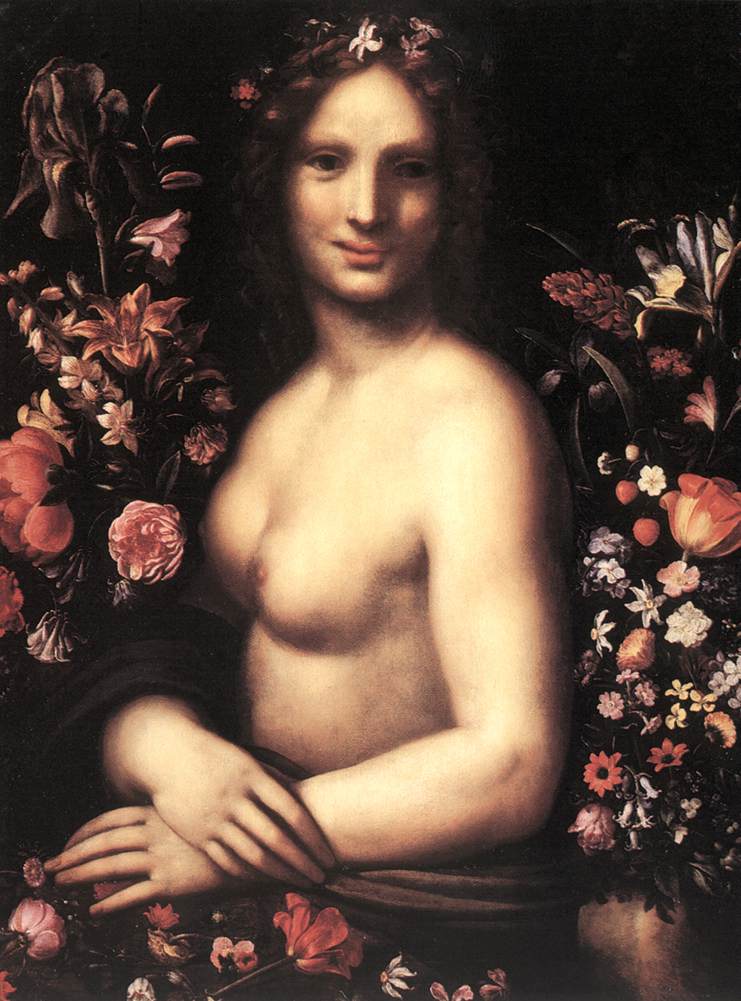

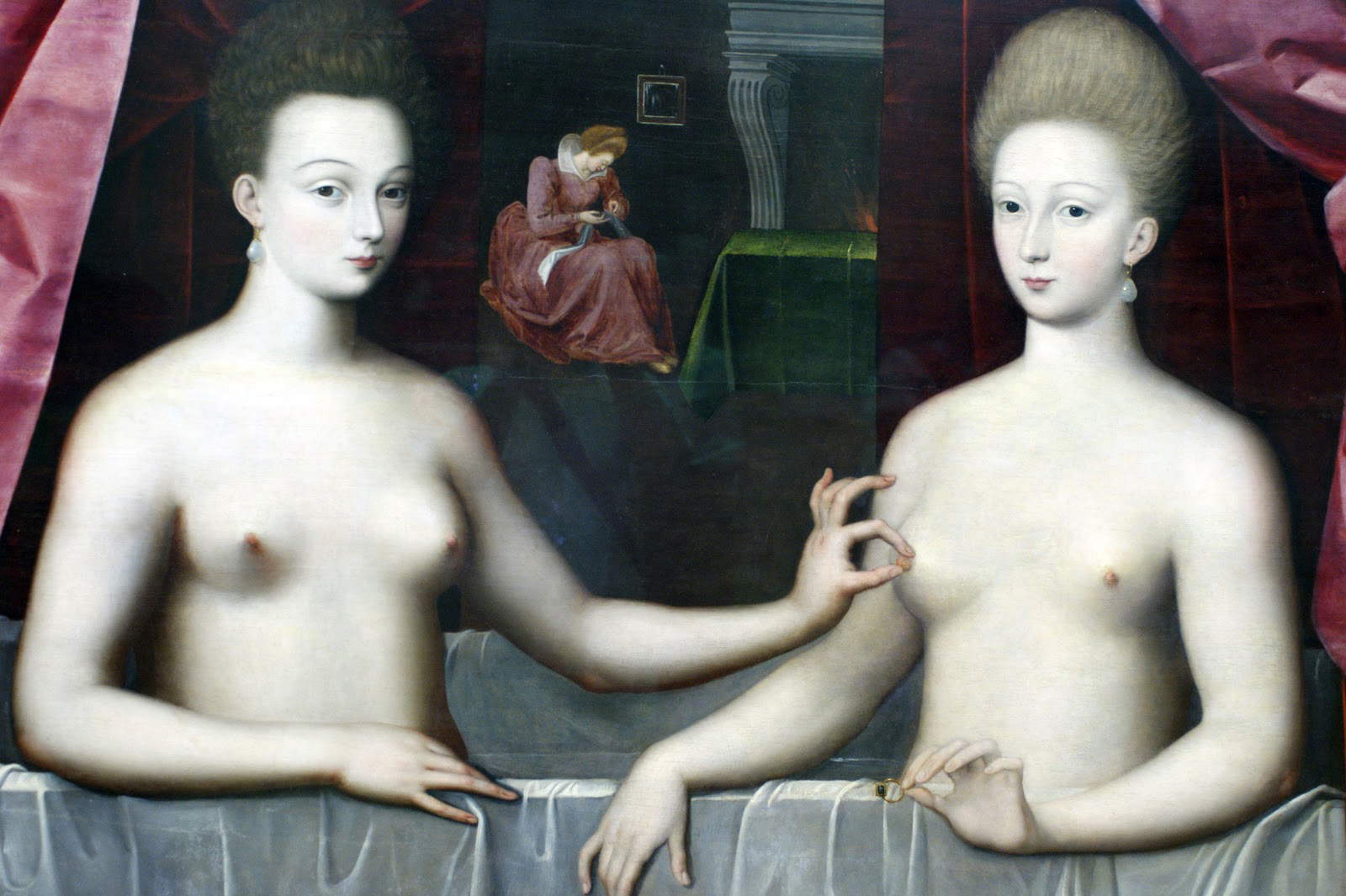

To remain in the realm of derivations and without trespassing yet into that of copies or variants, the best known is surely the so-called Mona Lisa nude, also known as Mona Vanna, a drawing from the school of Leonardo da Vinci, preserved at the Musée Condé in Chantilly, and from which more famous painting counterparts are derived: the one in the Museo Ideale Leonardo da Vinci, which one would like to attribute to Gian Giacomo Caprotti known as the Salaì (Oreno, 1480 - Milan, 1524), the one from the circle of Joos van Cleve (Joos van der Beke; Kleve, 1485 - Antwerp, 1540), and the Flora by Carlo Antonio Procaccini (Bologna, 1571 - 1630). The Nude Mona Lisa almost slavishly replicates the pose of the Mona Lisa’s hands but, unlike Mona Lisa, Mona Vanna is nude, presents her breasts uncovered to the relative, and her gaze is markedly more frontal than in the more famous Louvre painting. The work is closely associated with Leonardo, who in all likelihood executed the prototype. In fact, we know that on October 10, 1517, Cardinal Louis of Aragon visited the Tuscan genius at his French residence, the castle of Clos-Lucé near Amboise, and the prelate’s secretary, Antonio de Beatis, noted that the two had observed three paintings, including a portrait of a “certain Florentine woman facta di naturale ad istantia del quondam magnifico Juliano de’ Medici.” The “magnifico Juliano de’ Medici” was Giuliano di Lorenzo de’ Medici (Florence, 1479 - 1516), lord of Florence from 1513 and duke of Nemours from 1515: Leonardo actually worked for him from 1513 until 1516 (but there are no connections between the Louvre’s Mona Lisa and the Florentine lord, which is why many have ruled out that the “dona” is the Mona Lisa, unless we want to call into question an unlikely relationship between Lisa Gherardini and Giuliano di Lorenzo de’ Medici, which is not documented by any source), and if we assume that the “nude Mona Lisa” is the “dona fiorentina facta di naturale” (where “fatta di naturale” could be taken to mean “nude”), then it is likely that Antonio de Beatis was referring to a painting by Leonardo that to this day has yet to be traced, but which evidently had to provide ideas and insights to his pupils. Then there is a notarial deed dated April 21, 1525, in which some property in Salaì’s possession is listed, and where the term “Joconda” appears for the first time, but a “quadro cum una meza nuda” is also mentioned, which could be Mona Vanna. The citation does not refer to the Chantilly cartoon, since the inventory only lists paintings and the term “painting” cannot indicate a drawing, but the work (assuming it was a work by Leonardo’s hand and not Salaì’s) probably must have been smaller or of lesser quality than the “Joconda,” which is valued at 100 scudi in the listing, compared to 25 for the “meza nuda.”

In a 2016 study, one of the most credentialed Leonardists, Martin Kemp, related the Chantilly cartoon to the painting that is closest to it, a nude Mona Lisa housed in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg and dated to around 1515. An analysis of the dimensions, which are entirely compatible (although the cartoon, moreover damaged by patches of moisture and abrasions, has been resected in both height and width), indicates that the St. Petersburg work was probably taken from the Chantilly cartoon, a sign that the drawing was most likely used in Leonardo’s workshop. Kemp then spotted some elements (the pentimenti in the fingers of the hand, some strokes that seem to have been executed by the hand of a very good draughtsman, left-handed as Leonardo was, some changes in the perforations of the outlines) that would suggest that Leonardo himself intervened in the cartoon, perhaps made by one of his assistants and then corrected by the master. In addition, the nude Mona Lisa introduces different elements, as we have seen, than the Mona Lisa, a sign that it is, according to Kemp, an invention independent of the Mona Lisa, and not a derivation of it. One can therefore wonder, at this point, about Leonardo’s motives for imagining such a work (for an invention that, according to Kemp, has always been underestimated by art historians, because the painting made by Leonardo, assuming it ever existed, is not preserved, and because we do not know whether he is really the author of the Chantilly cartoon): an unconventional subject that, Kemp writes, “is simply what it is: a provocative image of a woman unashamedly revealing her body to the viewer, and looking straight ahead in a direct, purposeful manner, with an ambiguous smile. It has an obvious pornographic dimension, or at least it did when the work was made.” It would not, therefore, be a portrait, as the name by which the work is universally known would suggest (“monna Vanna” is the conventional name given to the painting based on the hypothesis that it depicts a mistress of Giuliano de’ Medici who went by that name), nor would it be a study to better analyze the pose of the Mona Lisa, as Kenneth Clark speculated.

Of the nude M ona Lisa herself there are some 20 versions, including copies and variants. In fact, the work, as the exhibition La Joconde nue, which was held precisely at the Château de Chantilly from June 1 to October 6, 2019 (and it was the first exhibition dedicated to the work), enjoyed a certain popularity among sixteenth-century artists, and would eventually give rise to a true genre, that of ladies at the bath: The Portrait of Gabrielle d’Estrées and her sister the Duchess of Villars, by an unknown author, is very famous, and the same can be said of a painting chronologically closer to Leonardo, the Dame au bain by François Clouet (Tours, 1515 - 1572), which in turn derives from Joos van Cleve’s version. The spread of the subject was probably due to François I’s interest in the nude (his collection included several nudes, both ancient and modern, in both painting and sculpture), and perhaps to pander to the current taste numerous artists adapted. Beginning with the one who painted the most famous painted nude Mona Lisa, the one in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, formerly attributed to Leonardo himself and also to Salaì: today, however, there is a tendency not to name its author, although everyone agrees that it is a product of Leonardo’satelier, and of an artist obviously less talented than the great Tuscan (just look at the hair, which is too flat, the more abrupt chiaroscuro transitions, and the simplified landscape compared to that of the Mona Lisa). Italy, too, has its own nude Mona Lisa: it is the one, mentioned above, in storage at the Museo Ideale Leonardo da Vinci in Vinci, also made by Leonardo’s circle (perhaps, as mentioned, by Salaì, but there is no certainty about this), and a work of considerable importance since scientific studies carried out just before the above exhibition ascertained that it was made from the Chantilly cartoon.

|

| Leonardo da Vinci’s circle, Nude Mona Lisa (c. 1514-1516; charcoal and white lead on paper, 724 x 540 mm; Chantilly, Musée Condé) |

|

| Gian Giacomo Caprotti known as the Salaì (?), Nude Mona Lisa (1515-1525?; oil on panel transported on canvas; Private collection, on deposit in Vinci, Museo Ideale Leonardo da Vinci) |

|

| Circle of Leonardo da Vinci (?), Nude Mona Lisa (1515-1525?; oil on panel transported on canvas; St. Petersburg, Hermitage) |

|

| Circle of Joos van Cleve, Female Portrait (16th century; oil on panel; Prague, Národní Galerie V Praze) |

|

| Carlo Antonio Procaccini (attributed to), Flora (c. 1600; oil on canvas; Bergamo, Accademia Carrara) |

|

| School of Fontainebleau, Alleged Portrait of Gabrielle d’Estrées and Her Sister the Duchess of Villars (c. 1600; oil on panel, 96 x 125 cm; Paris, Louvre) |

|

| François Clouet, Dame au bain (1571; oil on panel, 92.3 x 81.2 cm; Washington, National Gallery of Art) |

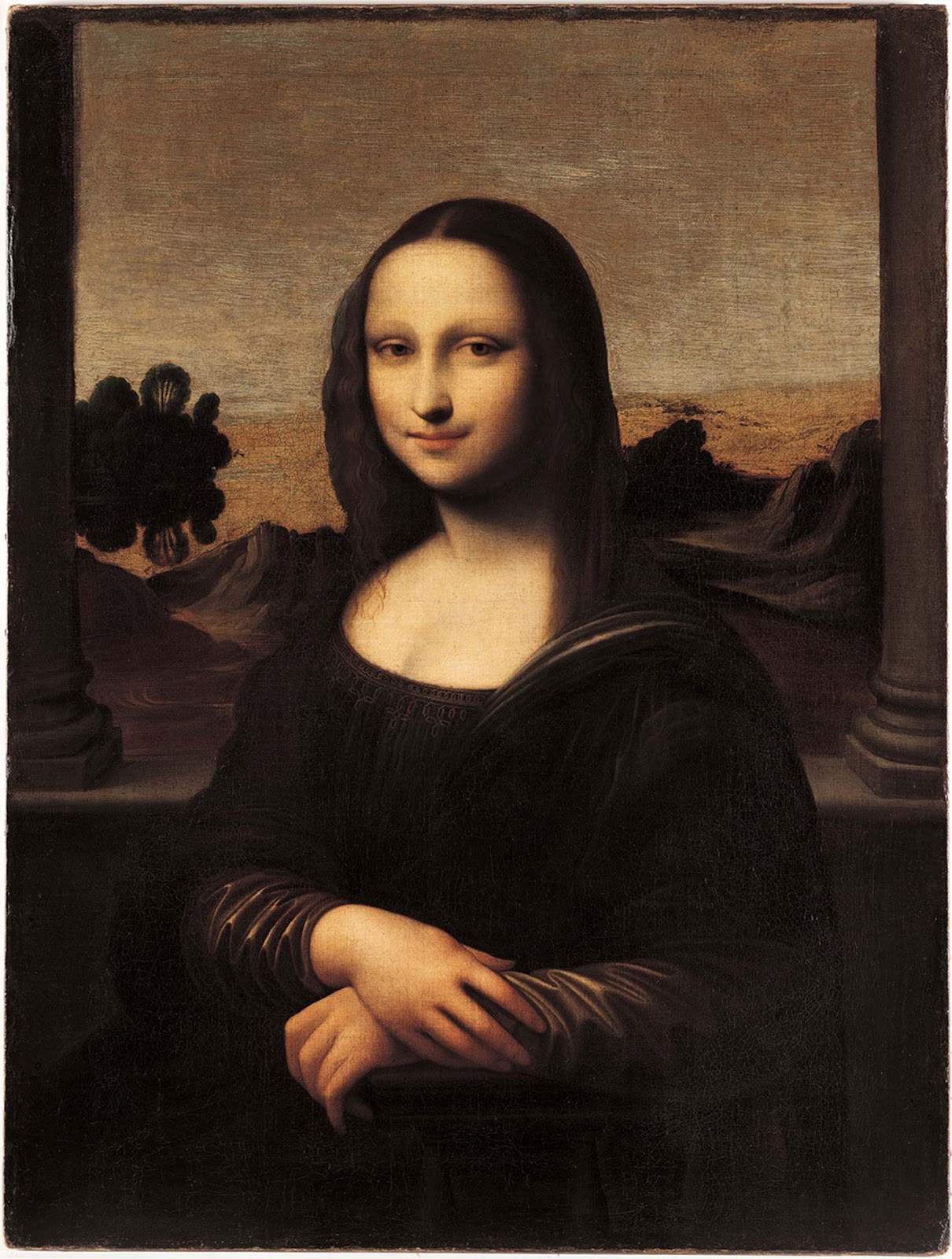

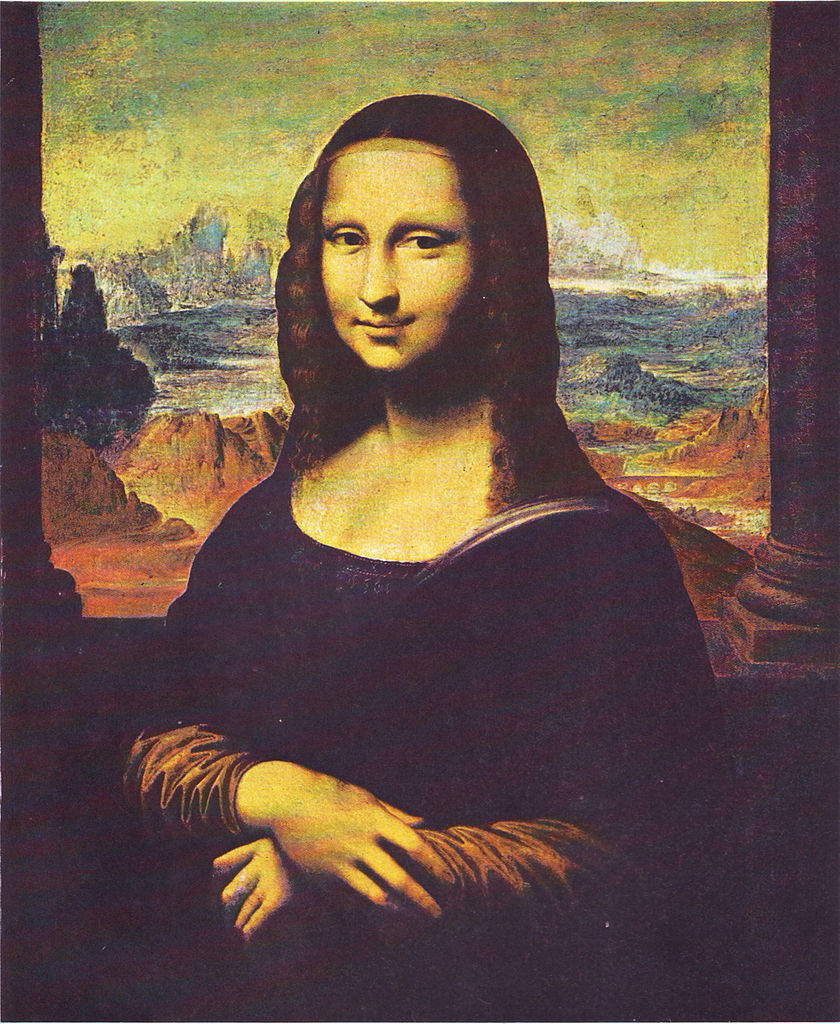

Of the variants, the most famous is probably the Prado’s Mona Lisa, which is also useful because, of the many versions of the Mona Lisa, it is the one that has the colors closest to those that a sixteenth-century viewer could see shortly after the painting was finished: we have to imagine the archetypal Louvre painting with similar colors as well. Today we see the Mona Lisa yellowed due to the action of time: however, for the reasons Professor Dal Pozzolo has eloquently explained on these pages, it is unlikely that an intervention will be carried out that will restore Leonardo’s masterpiece to its sixteenth-century colors. Returning to the Prado panel, the latter has a contemporary date with that of the Mona Lisa in the Louvre (critics place it between 1503 and 1519: this dating makes this painting the oldest known variant of the Mona Lisa ), but we do not know who painted it: it is not by Leonardo da Vinci, because it does not reach the quality of the master’s works (for example, it can easily be seen that the Prado’s Mona Lisa lacks shading altogether, a detail that reveals a sensibility far removed from Leonardo’s), but it is definitely the work of an artist from his circle, although it has not yet been possible to establish a name with certainty, although those of Salaì and Francesco Melzi (Milan, 1491 - Vaprio d’Adda, 1570) have been proposed. The Prado’s Mona Lisa is believed to be first recorded in 1666, in an inventory of the Galería del Mediodía of the Alcázar in Madrid as a “mujer de mano de Leonardo Abince” (“woman from the hand of Leonardo da Vinci”), and at that time she was already the property of the Spanish royal family. It would arrive at the Prado in 1819, and it is interesting to note that the famous French writer Prosper Mérimée also spoke of the work, in a letter sent in 1830 from Spain (where the author was at the time), to the editor of the Revue de Paris, where he says that “among the works of Leonardo da Vinci, I have been impressed by a Mona Lisa that seems to be a variant, with some modifications, of the one we have in the Louvre. Instead of that fantastic landscape, full of those sharp rocks so dear to Leonardo da Vinci, the background is gloomy and flat.”

Indeed, there is a point to be made that the Prado’s Mona Lisa, until 2012, looked yellowed and on a dark background, so much so that, before then, many did not even consider it a work of Leonardo’s scope. Only a restoration conducted that year had made it possible to discover what its original appearance was: technicians at the Madrid museum had realized, through infrared reflectography, that beneath the black blanket behind the lady effigy was a landscape quite similar to that of the Mona Lisa in the Louvre, and analysis had ascertained that the dark background was the result of a repainting after 1750. The restoration conducted by Almudena Sánchez Martín, which removed repainting and overlays, restoring the work’s legibility thanks to the recovery of colors and transparencies (and, we repeat, also making us understand what the original Mona Lisa must have looked like originally), also revealed that the author of the painting used high-quality materials, such as those used in Leonardo’s workshop. Thus, it was discovered that the walnut wood panel is similar to that used for masterpieces such as the Lady with an Ermine or the Belle Ferronnière, and that the imprimitura in white lead and linseed oil is identical to that found in several works by Leonardo and his circle, but not only: the most interesting discovery concerns the preparatory drawing, which is identical (it, too, was analyzed by infrared reflectography), and especially in the Prado version it has the same corrections found in the Mona Lisa (the outline of the waist and head, the position of the hands), a sign that the author of the Madrid painting followed Leonardo while he was painting the Louvre picture. Therefore, it is not a simple copy, because the copyist worked on the finished work, and it is therefore very difficult for him to make corrections: with the Mona Lisa in Madrid we are in the presence of an artist who worked in close contact with the master.

Another interesting case is that of the Mona Lisa of Isleworth, so called because in the early 20th century it was owned by the English merchant Hugh Blaker, a resident of the English town of Isleworth. It is a very peculiar work because it looks like a “young,” almost adolescent version of the Mona Lisa: unfinished (the landscape behind the lady is barely sketched), wider than the Mona Lisa in the Louvre, and with two columns at either end, similar to those found in Raphael’s drawing discussed above. It is precisely the columns that are an important element in the debate over the authorship of the Isleworth Mona Lisa: in the past it was believed that the Mona Lisa in the Louvre also had columns on the sides (and that therefore both Raphael’s drawing and Isleworth’s version were two direct derivations from the Parisian work), but in 1993 an analysis by the scholar Frank Zöllner ascertained that the Mona Lisa was not cut off at the sides, and this led many art historians to assume the existence of another version of the Mona Lisa that Raphael must also have been inspired by. Not least because a well-known sixteenth-century painter and treatiseist, Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo (Milan, 1538 - 1592), in his 1584 Treatise on the Art of Painting, speaks of portraits “by the hand of Leonardo, adorned in the guise of a spring, like the portrait of the Mona Lisa and Mona Lisa, in which he has expressed among other parts marvelously the mouth in the act of laughing.” Lomazzo’s sentence would thus suggest that the Mona Lisa and the Mona Lisa are two separate paintings. However, at present, this Earlier Mona Lisa (by this name it is known in England and English-speaking countries), now held in a private Swiss collection (the first record of this painting, in England, dates back to 1778: purchased by the aforementioned Blaker in 1914, the work passed in 1962 to collector Henry Pulitzer, who bequeathed it to his wife Elizabeth Meyer, and after the latter’s death in 2008, it was purchased by an international consortium of private individuals through the initiative of The Mona Lisa Foundation), has not yet found a name. It would not be Leonardo, as believed by Martin Kemp, among the most vocal disputants of Leonardo’s authorship of this work, according to whom no one among “serious” Leonardo specialists would argue in favor of an attribution to the Vinci artist: executed on canvas (a medium not found in any known work by Leonardo), flatter than Leonardo’s ladies, lacking their psychological depth, clothed in a robe conducted more schematically than that of the Louvre’s Mona Lisa and with stiffer draperies, Isleworth’s Mona Lisa is probably the work of an imitator or artist in the circle.

|

| Circle of Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa (1503-1519; oil on panel, 76.3 x 57 cm; Madrid, Museo del Prado) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci’s circle, Mona Lisa, Prado Museum, before restoration |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci’s circle, Prado Mona Lisa, infrared reflectography |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci’s circle (?), Mona Lisa of Isleworth (16th century; oil on canvas, 86 x 64.5 cm; Private collection) |

As for copies, there are a number of them all over the world, as mentioned at the beginning. For some of them there have also been attempts in the past to attribute them to Leonardo da Vinci, but these have always been discarded by critics because none of the copies reaches the quality of the Mona Lisa in the Louvre. One of the errors most frequently found in the copies, especially the older ones, is the line of the balustrade behind the lady: in many copies, the portion on the right appears slightly lowered than that on the left (Adolfo Venturi was already convinced that this would be an error that Leonardo would not have made, and according to the great scholar this is a diriment element in disfavoring an attribution to the genius from Vinci). In general, however, all known copies appear to be more scholastic works than the real Mona Lisa, more rigid, less expressive, lacking the depth of the original, often unable to equalize the master’s sfumato. Moreover, for copies it is also very difficult to establish the name of the author. There is one, preserved at the National Gallery in Oslo, Norway, that is signed Bernardino Luini, but the style is incompatible with that of the Leonardesque artist, and it is rather thought to be a version made in the seventeenth century by Philippe de Champaigne (Brussels, 1602 - Paris, 1674), a painter best known for his work as a portrait painter. One of the most interesting copies is the so-called Vernon Mona Lisa, named after the collector (William H. Vernon) who owned it in the 18th century: it is believed to be a 16th-century work and, unlike many later copies, retains the columns on the sides. In the past, the Vernon family has tried several times to have its Mona Lisa authenticated as a Leonardo original (they had come close in the 1960s, when in an exhibition it passed as “attributed to Leonardo”--and there were even some who went so far as to say that the Vernon Mona Lisa is the original and the Louvre one the copy!), but we are still far from the genius’ inspiration, and today it is considered the work of an anonymous sixteenth-century artist.

Among the best quality copies, as revealed by a survey carried out in 2005 on the painting, there is then the so-called Reynolds Mona Lisa, so called because it was once in the collection of the great English painter Joshua Reynolds (Plympton, 1723 - London, 1792): the artist acquired it in 1790 from Francis Osborne, fifth Duke of Leeds, probably in exchange for a portrait. Reynolds’ Mona Lisa is supposed to be a century younger than the Louvre original (despite Reynolds being convinced that he had a work by Leonardo on his hands); it is attributed to an anonymous French artist (in fact, it is believed to have come from France, or at least northern Europe: according to examinations in 2005, the materials used by the anonymous copyist are those that were used in northern Europe in the late 16th and early 17th centuries), and it is in a better state of preservation than the Mona Lisa in the Louvre: the colors in which it appears can thus give us a further idea of what the Mona Lisa kept in Paris originally looked like. On the other hand, a private collection Mona Lisa passed at auction at Sotheby’s in 2019, which sold for an extraordinary result: $1.695 million (an outstanding figure for an anonymous artist!), against an initial estimate of $80-120,000, presents itself obscured. Unlike Vernon’s Mona Lisa and Reynolds’ Mona Lisa, the columns do not appear in this one, but in the face and landscape it is closer to the original, so much so that it is considered one of the highest quality copies: moreover, it could be a copy of Italian provenance, since it is believed to have once belonged to the noble Pistoiese family of Pistoj. Not of the same quality, however, is the copy in the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, which appeared on the market in the early twentieth century, and in which the columns return, and where the copyist, another anonymous seventeenth-century artist, once again attempts to imitate Leonardo’s sfumato, but with poor results, and the face of the Mona Lisa seems almost aged. Columns also appear in the St. Petersburg copy, another 17th-century version.

A copy with a curious history is the one kept at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Quimper, a coastal town in Brittany: a 16th-century work by an Italian copyist, it is very similar to the Mona Lisa in the Louvre (although narrower on the sides, it shows the same signs of time on the surface and the shading imitates that of the master well), and for this reason the French authorities thought of exhibiting it in 1911 in the Louvre immediately after the theft of the original Mona Lisa by the Italian painter Vincenzo Peruggia. The aim was to conceal the fact from the public, but the hypothesis waned immediately because the newspapers immediately reported the theft. To remain in Italy, the so-called Torlonia Mona Lisa, known by this name because it once belonged to the collections of the noble Roman family, has caused discussion in the 2019 Leonardo celebrations: owned by the National Galleries of Ancient Art, it had been granted on deposit since 1925 to the Chamber of Deputies and everyone had forgotten about it, until, on the occasion of the 500th anniversary, Senator Stefano Candiani noticed the panel and, after having it analyzed and restored, wanted to have it displayed in an exhibition, which was held at the Villa Farnesina from October 3, 2019 to January 13, 2020, and where other items of Leonardo’s scope were on display. On the occasion of the exhibition at the Farnesina, the work was given a sixteenth-century date and was assigned to an unknown painter from the circle of Leonardo da Vinci (in the Palazzo Barberini catalog published in 2008 it was attributed, albeit dubiously, to Bernardino Luini, on the basis of a nineteenth-century report that, however, would no longer be reflected in the Torlonia inventories). Other good copies are those preserved at the Walker Art Museum in Liverpool and the Alte Pinakothek in Munich.

|

| Philippe de Champaigne (?), Mona Lisa (17th century; Oslo, Nasjonalmuseet) |

|

| Sixteenth-century Anonymous, Mona Lisa (16th century; Vernon Collection) |

|

| Sixteenth-century French anonymous, Mona Lisa known as Mona Lisa Reynolds (16th century; Private collection) |

|

| Anonymous seventeenth-century French anonymous, Mona Lisa (17th century; oil on panel, 73.5 x 53.3 cm; Private collection). Sold at auction by Sotheby’s in 2019 |

|

| Seventeenth-century Anonymous, Mona Lisa (c. 1635-1660; oil on canvas, 79.3 x 63.5 cm; Baltimore, Walters Museum of Art) |

|

| Seventeenth-century Anonymous, Mona Lisa (17th century; oil on panel; St. Petersburg, Private Collection) |

|

| Seventeenth-century Anonymous, Mona Lisa (16th century; oil on canvas, 73 x 58 cm; Quimper, Musée des Beaux-Arts) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci circle, Mona Lisa known as Mona Lisa Torlonia (16th century; oil on panel; Rome, Gallerie Nazionali d’Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini) |

|

| Seventeenth- or eighteenth-century anonymous, Mona Lisa (17th-18th century; oil on canvas, 80.2 x 58.6 cm; Munich, Alte Pinakothek) |

|

| Anonymous seventeenth-century, Mona Lisa (17th century; oil on panel, 82 x 56.5 cm; Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery) |

In conclusion, it is necessary to point out that although attempts at attribution to Leonardo da Vinci have been made for several copies, at the moment none of them is ascribed with conviction to his hand, and in those few cases in which people still insist on attributing a certain copy to the master, these are always mostly isolated positions and in any case do not enjoy the support of most of the scientific community. All the copies in circulation and all the variants of the Mona Lisa that we know of at the moment are therefore works either by artists from Leonardo’s circle (but even in this case, establishing the names of the authors is often a very difficult task), or by copyists whose identity we do not know. So, if visiting a museum other than the Louvre, one comes across a Mona Lisa... one can be sure that it is not the work of Leonardo da Vinci. Then, as we have seen, from the documents it would seem to be open to the hypothesis that Leonardo himself painted at least two “Mona Lisa”... but at the moment these are theories not yet supported by evidence. Therefore, it is highly likely that the Mona Lisa in the Louvre will remain for a long time to come the only one where Leonardo’s genius can truly be recognized.

Essential Bibliography

- Costance Moffatt, Sara Taglialagamba (eds.), Illuminating Leonardo, Brill, 2016

- Laure Fagnart, Léonard de Vinci en France: collections et collectionneurs, L’Erma di Bretschneider, 2009

- Pietro C. Marani, La Gioconda, Giunti, 2003

- AA.VV., Dessins italiens du musée Condé à Chantilly, Reunion des Musées Nationaux, 1997

- Maria Teresa Fiorio, Pietro C. Marani, I Leonardeschi a Milano: fortuna e collezionismo, Electa, 1991

- Paul Joannides, The Drawings of Raphael with a Complete Catalogue, University of California Press, 1983

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati

Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da

Federico Giannini e

Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato

Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009.

Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamo

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.