Pablo Picasso (Málaga, 1881 - Mougins, 1973) came late to ceramics. It was not that he had never had the opportunity to see it up close, or even to try his hand at this very ancient medium of expression: he was in his early twenties when he discovered it in Paris, thanks to his friend Paco Durrio (Francisco Durrio de Madrón; Valladolid, 1868 - Paris, 1940), with whom he studied Gauguin’s ceramics and began to explore the possibilities that ceramics would offer him, and with whom he also began to model some sculpture. They were, however, experiments without a systematic character, sporadic, as when in 1929 he painted a vase made by the Dutch potter Jean van Dongen (Delfshaven, 1883 - Marly-le-Roi, 1970), but his passion for ceramics was still far away. The opportunity to delve into this technique came in the postwar period: in 1946 Picasso was staying in Antibes, and the summer of that year he went for the first time nearby, to Vallauris, a village on the French Riviera famous for its ceramic production. With World War II behind him, success, artistic maturity and even a certain personal peace of mind having arrived, Picasso could devote himself totally to ceramics: after visiting the Madoura ceramics factory, he had the idea of tracing on paper some ideas with which he then went back to Madoura the following summer, with the idea of transforming the ideas into products. A meeting with Suzanne and Georges Ramié, the owners of the manufactory, was decisive: he had met them at an exhibition in 1946. That same afternoon he had visited them in their workshop and had already tried to make some figures. With the Ramiés, the Spanish artist was not only able to learn the techniques, thanks in part to the help of Jules Agard (Grans, 1871 - 1943), the most talented of the ceramists who frequented the Ramiés’atelier, but also to integrate himself into the Vallauris community. In the Provençal town, Picasso stayed until 1954, having moved there with his entire family, and working regularly in Madoura’s workshop.

“It is noteworthy,” explains Harald Theil, who together with Salvador Haro González curates the exhibition Picasso. The Challenge of Ceramics (at the Museo Internazionale della Ceramica in Faenza from Nov. 1, 2019 to April 13, 2020), “the fact that his ceramic work did not arise from a spontaneous impulse. After his first visit to ceramics in 1946, he began with preparatory drawings for three-dimensional ceramics, starting with the vase that he transformed into human or animal representations. We know of seventy sheets of preparatory drawings for ceramic forms. They show that Picasso’s first ceramic activity was not accidental, but, rather, the result of reflection and preparation. In this sense, the creative process is the same as that followed for his sculptures and paintings, starting with drawings using the method of series, variation and metamorphosis.” Ceramic objects became the object with which Picasso conducted his experiments, so much so that he almost completely abandoned painting and sculpture: in a single year, the artist produced a thousand pieces, many of which are also preserved today in Italian public collections (starting with that of the MIC in Faenza). Not only that: thanks to ceramics, in Vallauris Picasso also tried out a new way of working, a more collaborative one, he who was an artist little inclined to collaborations (except for the one with Braque at the beginning of his career, until the Vallauris experience there would be nothing more like it in his whole career: with Agard and the Ramiés, in fact, relations were very close, and then ceramics, to succeed well, needed excellent teamwork from the whole workshop staff). Picasso loved the fact that ceramics combined painting and sculpture together: thus, he happened to model vases that looked like real sculptures (this is the case, for example, of the Vase-woman with amphora, a 1947-1948 work preserved at the Musée National Picasso in Paris), and to paint on plates. Although painting on ceramics was not like painting on an easel: when you paint on canvas, on board, on paper, or in any case on a support that is already ready, you see the results in real time. It works differently with ceramics: the colors can only be seen when the firing is completed, so the correct balance of the preparation (which appears grayish in color), for Picasso, also represented a kind of challenge (and it is also for this reason that the first pieces of Picasso’s ceramic production have a very reduced color range). And the same goes for the speed with which the work needs to be completed, because clay, as is well known, has absorbent properties, and in order to prevent the preparation from drying out too quickly, it is necessary to be quick: Picasso, moreover, used this characteristic to his advantage, because in this way he could give greater tension and dynamism to the subject depicted (see the Tray with Dove at the MIC in Faenza, where the bird seems almost in motion).

The artist was very attracted to this meeting of the elements, to the fire transforming the earth into an entirely new object. “The ancient concept of metamorphosis,” scholar Marilyn McCully has written, “is fundamental to understanding Picasso’s attitude toward ceramics: his works keep the two identities alive, without the former being completely negated by the latter. Thus, add example, a plate also becomes a head and a bottle can become a bird. She achieves these transformations either by manipulating freshly turned forms, as when she folds a clay bottle on itself and then compresses it to give it the shape of a dove, or by painting forms that are part of Madoura’s usual production.” This is what happens, for example, in the Bottle: kneeling woman made in Vallauris in 1950. Besides, Picasso liked to model clay with his hands: “the rarest and most magnificent element of his ceramics, are his hands,” said Georges Ramié. This fascination with contact with the material, one of the reasons why many artists work with ceramics, brought Picasso back to the ancient. Not least because ceramics is one of the oldest known art forms: for millennia man has been making utensils out of clay, and such an ancient and widely used art form also seemed to Picasso suitable for getting contemporary art to a wider audience. Thus, Picasso began to find his own sources of inspiration in ancient ceramics.

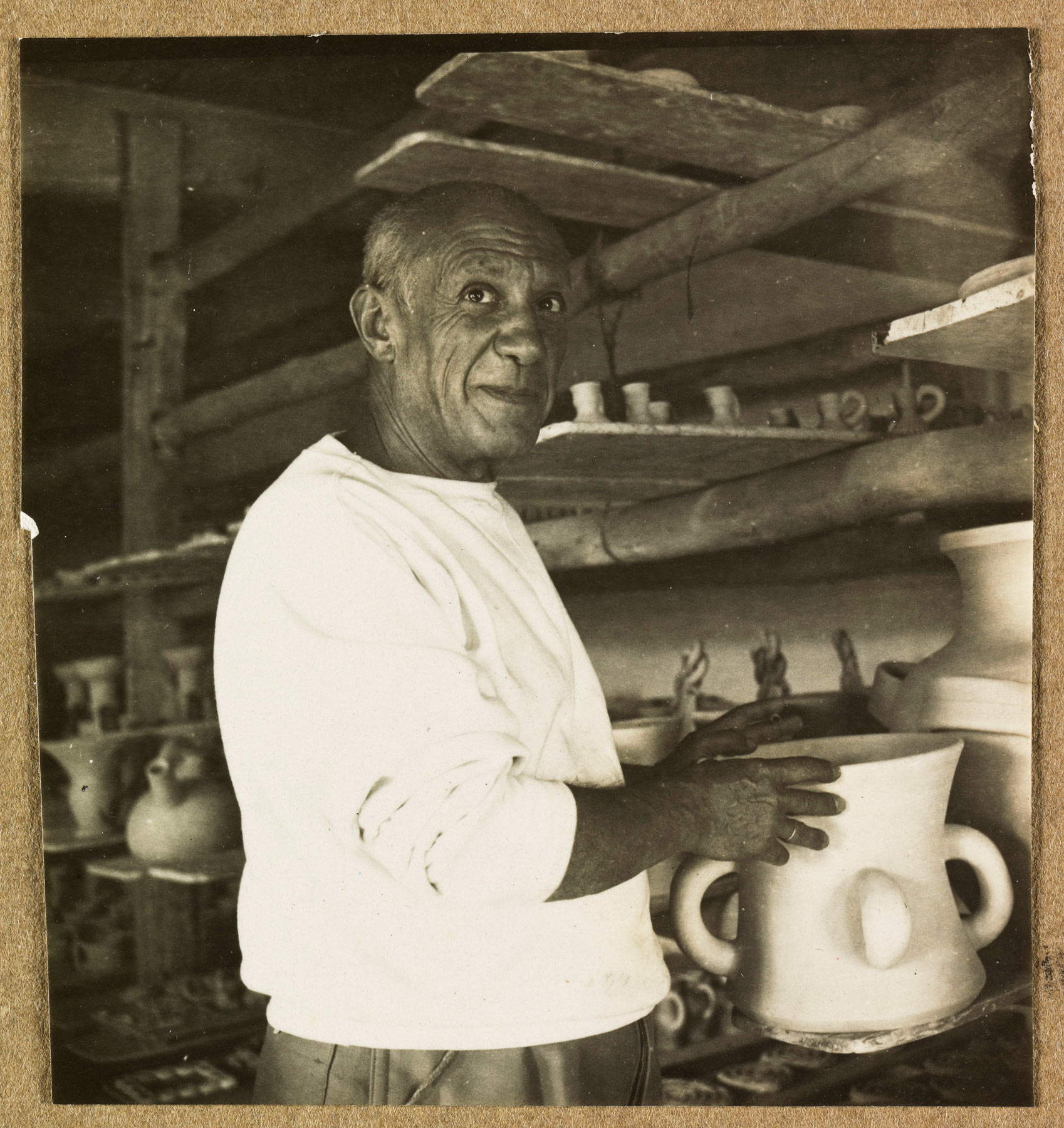

|

| Picasso in Madoura’s atelier in Vallauris |

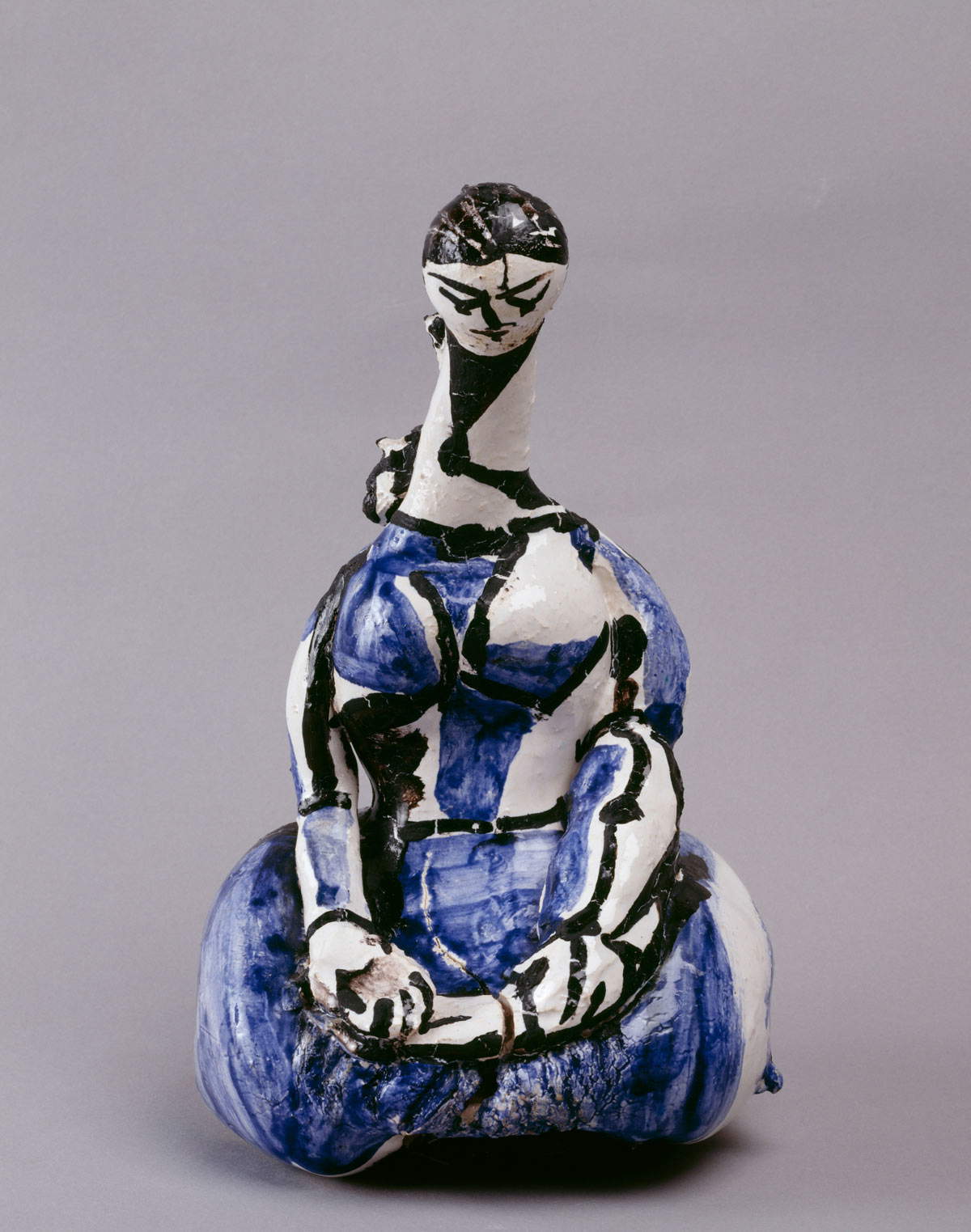

|

| Pablo Picasso, Vase: Woman with Amphora (1947-1948; Vallauris, October; white earth: turned, molded and assembled elements, engobe and white glaze decoration, incisions, patina after firing, 44.5 x 32.5 x 15.5 cm; Paris, Musée National Picasso). Ph. Béatrice Hatala |

|

| Pablo Picasso, Bottle: kneeling woman (1950, Vallauris; white earth: turned and shaped piece, decoration with oxides on white glaze, 29 x 17 x 17 cm; Paris, Musée National Picasso). Ph. RMN- Grand Palais (Musée National Picasso - Paris) / Béatrice Hatala |

|

| Pablo Picasso, Tray with Dove (October 1949, Vallauris; painted and glazed earthenware,32 x 38.5 cm; Faenza, Museo Internazionale della Ceramica) |

“Both in form and theme,” says Theil, “much of Picasso’s ceramics were deeply influenced by ancient Mediterranean civilizations and many other examples of the universal ceramic heritage.” The artist was inspired by “figurative vases in human or animal form, especially votive objects or others used for libations, to hold perfumes, or Etruscan funerary urns, Greek vases in the shape of female heads, or women.” Picasso was, after all, a great connoisseur of art history, had studied the art of ancient Mediterranean civilizations, and when he resided in Paris he did not miss an opportunity to go to the Louvre to study ancient artifacts (mythology, as is well known, played a decisive role in much of his art, not only on ceramics). And again, Theil explains, "Picasso owned many illustrated books related to ancient art and also used photographic sources, including many reproductions of ancient art published in the various issues of famous French art magazines such as Cahiers d’Art, Documents and Verve. Heavily inspired by the red and black figures of ancient Greek vases evoking Arcadian and Dionysian themes, this iconography appeared in his paintings after 1945, in modeled sculptures and in the subjects painted on his ceramics." Classical antiquity provided Picasso with a vast repertoire of stories, themes, figures with which to make objects over and over again. And even the objects themselves, such as the vase with Picador from MIC, which in shape resembles an oinochoe, a pitcher for pouring wine, and proposes the red-figure decoration invented in Athens in the sixth century B.C.

Thus, the motifs that animated his paintings or sculptures also return in ceramics, partly because Picasso was not accustomed to working in watertight compartments, and ceramics were not separate from painting or sculpture production: the Spanish artist’s output should be seen and evaluated as a single whole. Just by way of example, his celebrated Suite 347, the colossal series of etchings on which, between March and August 1968, Picasso poured much of his imagery, including fantasies derived from Greco-Roman mythology, has numerous points of contact with ceramics, especially on a technical level (in a 2015 essay of his own, Haro González, taking as an example the print Al circo: Horsewoman, Clown, and Pierrot, remarked that Picasso had used the aquatint technique, by which white figures are obtained by applying a varnish that repairs the plate from the etching process by which the dark parts are blackened, after having tried a similar process for a long time in ceramics: in several of his pieces, Picasso, instead of dipping the entire ceramic of the glaze, applied the latter with a brush only to certain portions, so as to create different areas of appearance and also capable of provoking different sensations to the touch). Returning to the relationship with antiquity in the Vallauris ceramics, his partner at the time, Françoise Gilot, who was with him between 1943 and 1953 and bore him his two children Paloma and Claude, recalled (Marilyn McCully reported this) that Picasso loved Cycladic idols, the kouroi of Greek art, and Etruscan funerary sculpture. In Vallauris, the source for his work, however, was not only his reminiscences of the Louvre, but also the illustrations he found in books published by his friend Christian Zervos, an art publisher whom the painter had met during his early years in Paris.Picasso, therefore, was “keenly aware of the enduring power of ancient forms,” McCully points out. “At significant moments in his career, Picasso often made vital leaps forward in his artistic development through the exploration of the secrets of primitive art”: and ended up discovering himself “capable of enslaving the magic of ancient art to his own creative power.” One of the most singular fusions of ancient and modern, of Picasso’s “magic of ancient art” and “creative power,” is the vase known as The Four Seasons, also preserved at the MIC in Faenza: here, Picasso exploits the flaring typical of the vessels produced by the Madoura manufactory to emphasize and enhance the features of the four women who appear on the surface of the vase, working with a technique unknown to ancient Greece, that of engobe. The artist, proceeding first by scratching to trace, through incisions on the clay, the naked bodies of the four young women, applied engobe, a compound used to give coloring to the work.

|

| Pablo Picasso, The Four Seasons (May 1950, Vallauris; terracotta scratched and painted with engobe, 65 x 32 cm; Faenza, Museo Internazionale della Ceramica) |

|

| Pablo Picasso, Picador (1952, Vallauris; terracotta with glaze, 13.2 x 11.5 x 8.2 cm; Faenza, Museo Internazionale della Ceramica) |

Ancient art was not only a source of decorative motifs. It has been said that mythology plays an important role in Picasso’s art: therefore, many motifs from mythology are also found in ceramics. It has been pointed out, however, that the function of the repertoire inferred from the stories of ancient Greece changes: if in the 1930s and during World War II mythology in Picasso was a harbinger of disquiet, with its violent and brutal charge (think of the figure of the minotaur and its importance in Picasso’s art during the years of the dictatorships), in Vallauris everything is pervaded by an unprecedented joie de vivre. And Joie de vivre is, indeed, the title of one of his famous paintings made in October 1946: with the conflict over, and some tormented personal events left behind as well (starting with the death of his mother Maria Picasso López, who died in 1939), it is time for rebirth, for celebrating peace. Thus, in the large painting now housed at the Musée Picasso in Antibes, we witness a joyous dance: a nude nymph (perhaps Françoise Gilot herself) dances with a tambourine in the center of a composition where light, restful tones prevail, following the sound produced by a centaur’s fife on the left and the diáulos, the double flute, played by the faun who closes the group on the right, completed by two kids jumping near the woman. In the background is the Côte d’Azur sea ploughed by a boat, and all around are meadows, flowers, and trees. A lyrical, buoyant, luminous atmosphere reigns; it is a painting that expresses the happiness that had pervaded the artist: the mythological stories are no longer stories of violence, but are set in an idyllic Arcadia where everything is festive, somewhere between the ancient fable and the colorful triumphs of Matisse’s Le bonheur de vivre.

Satyrs, fauns, centaurs, dancing girls are the characters that populate Picasso’s paintings in this period. And ceramics, of course. “It’s strange,” Picasso asserted, “in Paris I had never drawn fauns, centaurs, or heroes of mythology-I always had the impression that they lived here.” This was not true, because in any case Picasso had sometimes drawn fauns and centaurs in Paris, but after 1946 these figures took on new meanings. These characters, which appear frequently in Vallauris’s ceramics (see, for example, the Ithyphallic Centaur of 1950, or the Face of a Tormented Faun of 1956, not to mention animals in any case linked to mythology that return frequently in his production, as in the case of the owl, an animal linked to the goddess Athena), symbolize the artist’s return to life, to nature, to love. They are the characters that populate the tales of the protagonists of the bucolic poetry of classical antiquity. And they become recurring motifs in Picasso’s art of this period, marked by joy, harmony, perhaps even a slight sense of nostalgia.

|

| Pablo Picasso, Centaur (ca. 1950, Vallauris; painted terracotta, 18.7 x 18.4 x 1.5 cm; Faenza, Museo Internazionale della Ceramica) |

|

| Pablo Picasso, Face of Tormented Faun (1956, Vallauris; painted and glazed earthenware, 3.7 x 42.5 cm; Faenza, Museo Internazionale della Ceramica) |

|

| Pablo Picasso, Owl with female head (1951 - February 27, 1953, Vallauris; White earthenware: casting. Decoration with engobe and pastel, 33.5 x 34.5 x 24 cm; Paris, Musée National Picasso Paris). Ph: RMN- Grand Palais / Mathieu Rabeau |

Picasso’s greatness, it is known, also lies in his ability to constantly renew himself, on all levels: thematic, stylistic, technical. The artist also demonstrated this with ceramics, which represents a long and important moment in his artistic journey, as we have seen. “Picasso,” argues Haro González, “was able to assimilate all the particular technical characteristics and stylistic traditions inherent in the ceramic medium while maintaining the ability to redirect them toward new horizons and toward his own way of understanding artistic creation. In fact, his ceramic production is an inseparable part of his entire oeuvre. That is to say, it is not possible to understand Picasso’s work in a specific discipline, in isolation, but only by considering the artist’s entire oeuvre as an organic and rhizomatic whole, in which all elements are closely related.”

Not only that, Haro González says that ceramics, for Picasso, also had an ulterior goal, a “democratic” goal as the scholar defines it: “Picasso wanted his art to reach the general public and to break away from the exclusive domain of collectors of his art. Pottery was a popular art form, and since ceramic objects were part of everyday life, they could help create a closer proximity to modern art.” A modern art capable, however, of rereading the ancient with the urgency of a man and an artist strongly tied to his time, who knew how to revive classical art by pouring all his anxieties, joys, and feelings into the characters who animated his works. And ceramics was no exception.

Reference bibliography

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.