Art history enthusiasts who frequent social networks are sure to have come across vignettes and "memes" (i.e., humorous images made by putting an ironic comment on a photograph that comes from a different context) a few times that play on theimpassibility of many of Perugino ’s (Pietro Vannucci; Città della Pieve, c. 1450 - Fontignano, 1523) Madonnas. One finds many of them, for example, on the now famous Mo(n)stre page that always disseminates entertaining content made from ancient works. Indeed, Perugino’s Virgins often look like this: the face slightly bent to the side, the mouth sealed, the expression imperturbable, the eyes conveying a sense of deep composure and participatory spirituality. These are the faces of Perugino who, as Umberto Gnoli had written, “brought to art figures new in grace and beauty, new expressions of recollection or religious fervor, languidness or ultra-earthly serenity.” The Madonna of the Confraternity of Consolation, one of the artist’s most recognizable works, preserved at the National Gallery of Umbria, may fall into the list.

It was commissioned to the artist in 1496 by the confraternity of the Disciplinati di Santa Maria Novella of Perugia, known as “i battuti”: it was intended to decorate the altar of their oratory located near Porta Sant’Angelo, although curiously it was also used as a processional banner, despite its bulk and weight. It took Perugino two years to complete the commission, an altarpiece more than six feet high that depicts the Virgin with the Child on her arm, two angels overhead with clasped hands in prayer and, further back, members of the confraternity (also called “of the Consolation,” hence the name by which the panel is known). However, the Disciplinati did not have sufficient resources to pay the artist, who at that time was already a renowned and therefore expensive painter: the artist initially refused to deliver the work, since he was accustomed to dismissing his works only after collecting all his due, and the confraternity members needed a contribution from the Municipality of Perugia, which guaranteed five disbursements to Perugino, to meet expenses. In addition, again the Municipality in 1499 provided the resources to build a chapel that would house the altarpiece. The cost of the work, 60 florins, was a price in line with other works by Perugino of similar format, such as the Resurrection of San Francesco al Prato painted in the same period (50 florins), or the Pala dei Decemviri (100 florins). However, the artist also fired much more demanding and expensive works, such as the Polyptych of St. Peter (now divided between the Louvre and the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lyon), which cost as much as 500 florins. These were high fees: an artist like Pinturicchio demanded similar sums, while pupils or second-rate painters usually charged one-fifth of what the more popular masters took.

The angel on the

The angel on the

The

The

Having narrowly escaped the Napoleonic spoliation (one of the brothers of the Confraternity had in fact hidden the altarpiece in his house, preventing the French soldiers from finding it), the Madonna of Consolation was later transferred in 1801 to theoratory of San Pietro Martire following the merger of the confraternity of Santa Maria Novella with that, precisely, of San Pietro Martire, after which, at the time of the post-unification suppressions, the painting became part of the collection of the then Pinacoteca Civica di Perugia, the future National Gallery, in 1863, where it was deposited by the confraternity members themselves: in 1906, the final donation to the collective patrimony was finally sanctioned. What may be a drawing executed in view of this work has survived: it is a kneeling Consister with clasped hands preserved at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, which in 1997 scholar Joseph Antenucci Becherer related both to the Madonna of Consolation and to the gonfalon of St. Augustine that is now in the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh and was made around 1500. The latter work also echoes the scheme with the brethren arranged around the main figure.

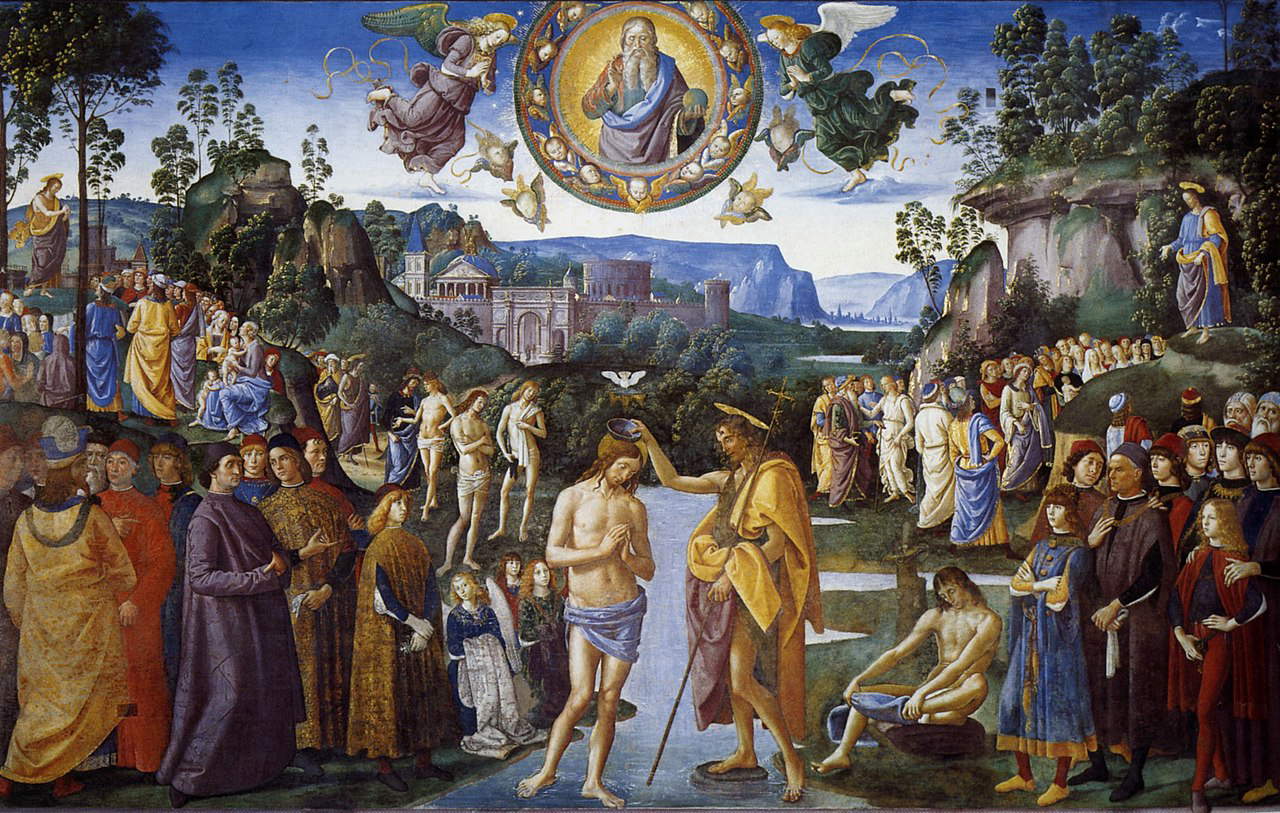

The architect Baldassarre Orsini (Perugia, 1732 - 1810), a countryman of the painter, wrote in 1803, in his work Vita, elogio e memorie dell’egregio pittore Pietro Perugino, that the artist “never painted works that could be said to be mediocre” (although he acknowledged that “in some he did not arrive to that high degree of beauty that one admires in his most excellent ones”), and among the works defined as “egregious” included precisely the Madonna of Consolation, “large in nature, seated on a seat, embracing her child, with beautiful, easy and soft manner.” The work is indeed significant, both for its mystical placidity and because here Perugino experiments with and fine-tunes a scheme and figure that would return at other times in his production: the Virgin and Child would be repeated by the artist, in almost identical but more schematic and less monumental forms, in the Tezi Altarpiece, executed around 1500 for the altar of the Tezi family in the church of Sant’Augustine in Perugia (this work is also in the National Gallery of Umbria, although the predella, with theLast Supper, was separated from the panel and is now in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin). The Madonna wears a red robe, a blue tunic and a green cape, is seated on a wooden stool and holds the Child on her lap: the infant Jesus is depicted, as per iconographic custom, in the act of blessing. On either side of the Virgin, here are the two angels in symmetry, depicted praying as they come flying in, resting their foot on a little cloud. They are two ethereal and delicate figures, and this lightness of theirs is further emphasized by the waving of their robes, which, compared to the early works (such as theAdoration of the Magi for the church of Santa Maria dei Servi) lose their earlier rigidity and become less heavy. These two symmetrical angels, invented by Perugino some fifteen years before the Madonna of Consolation (in fact, they are first seen in the Baptism of Christ frescoed in the Sistine Chapel, a work of 1482), would also return in numerous of his works: indeed, we see them around the figure of the risen Christ in the Resurrection painted for the church of San Francesco al Prato and now in the Vatican Pinacoteca, or in the Banner of Justice, which closely echoes the scheme of the Madonna of the Confraternity of Consolation.

Perugino,

Perugino,

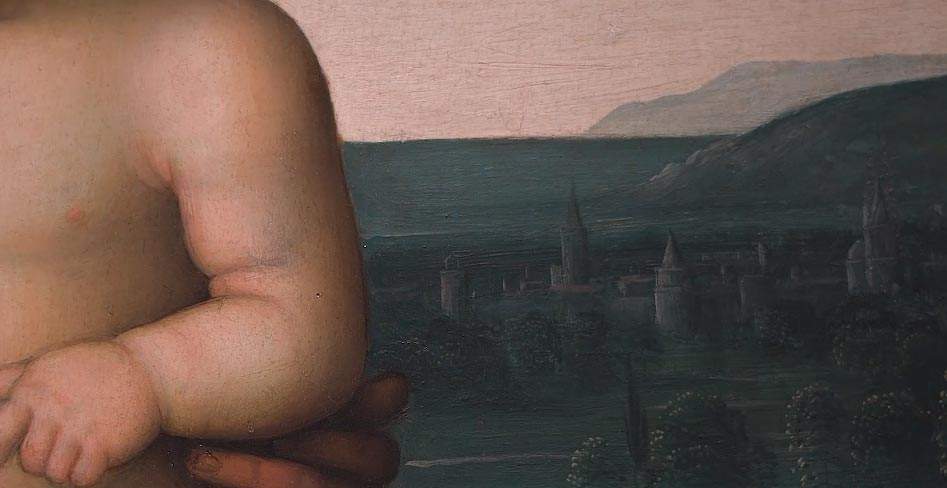

In the background, in front of an Umbrian landscape where a city can be glimpsed in the distance and where the expanse of water of Lake Trasimeno returns, a constant presence in the views that unfold behind the protagonists of the Perugian altarpieces (these were still the artist’s native lands, places dear to him), the members of the confraternity are arranged: six hooded figures, wearing white robes, on a smaller scale than the Virgin (a medieval legacy). Two figures have pinned on their chests a large badge with the image of the Madonna and Child, another element to spur the members of the confraternity to devotion.

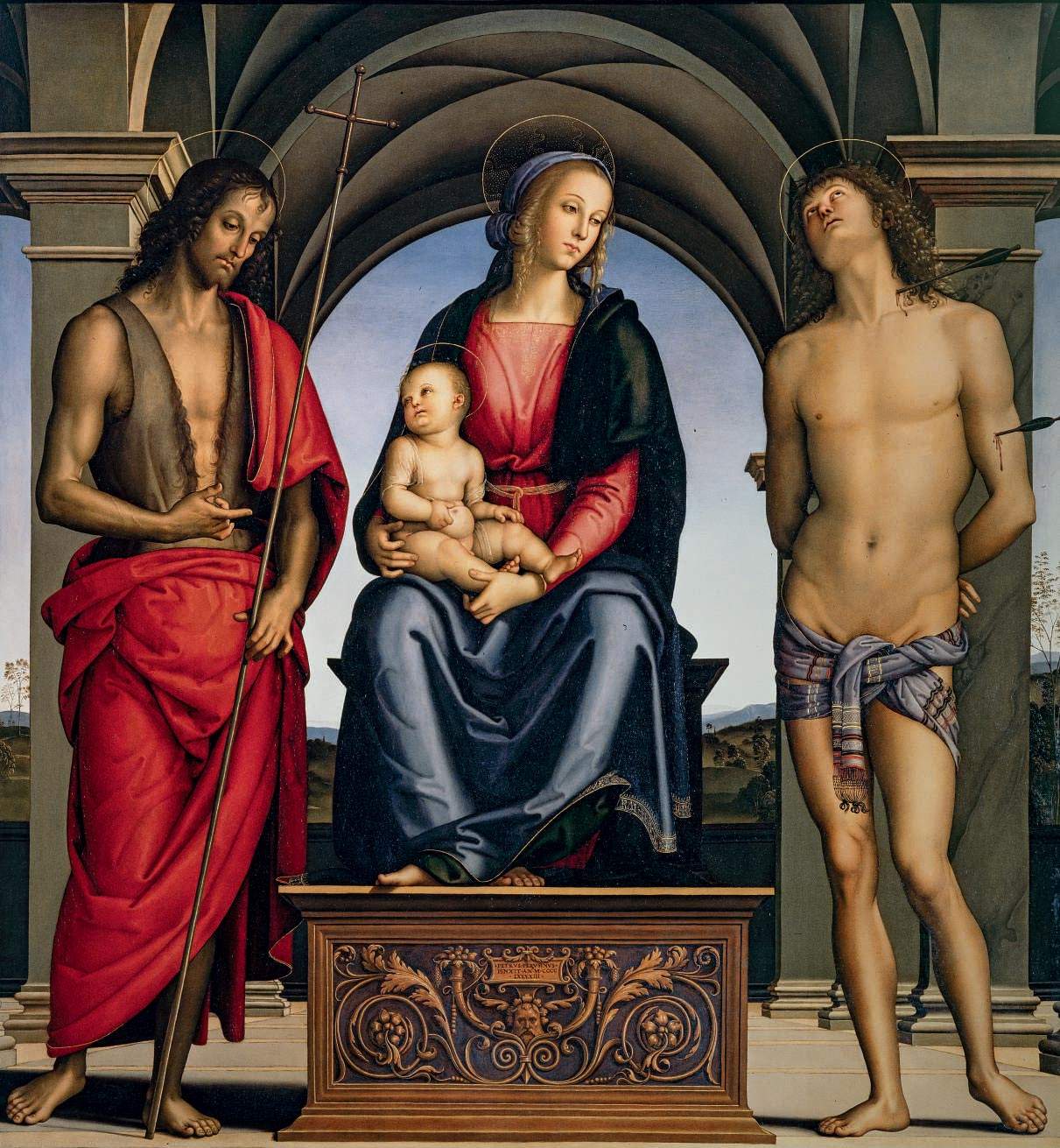

The Virgin’s pose and clothing are reminiscent of the Madonna and Child Enthroned between Saints John the Baptist and Sebastian, a work signed by Perugino and dated 1493, painted for the Salviati family and destined for the church of San Domenico in Fiesole, and now housed in the Uffizi Gallery. Perugino had distinguished himself for similar compositions: founded on symmetry, with simple schemes that were meant to inspire pleasantness and serenity, as well as move the faithful to contemplation (it will be necessary to recall that success came to Perugino at the time when Tuscany, where s’had trained and where he had long worked, was invested by the mystical fervor inspired by the fiery sermons of Girolamo Savonarola, and the Madonna of Consolation itself is painted at the moment when the final acts of the Ferrara friar’s historical and human story were being consummated). Here, then, is the reason for such seraphic expressions, for which Perugino’s Madonnas have become famous; here is why the artist, as Orsini wrote, “painted the faces of his Madonnas with very beautiful appearance and composure,” which, however, do not lack a certain vitality, often suggested by the movement of the shoulders and neck.

Moreover, according to a tradition that probably takes its start from an anecdote that Giorgio Vasari recounts in his Lives, Perugino’s young wife, Chiara Fancelli, married in 1493, has been sought to be identified in the Madonna, and the same tradition applies to other works where Madonnas with similar features appear. In fact, we read in the biography of Pietro Vannucci traced by the sixteenth-century historiographer that the artist “took for his wife a beautiful young woman and had children of her own; and he was so delighted that she wore graceful hairstyles, and outside and in the house, that it is said that he often styled her by his own hand.” From these few words about Chiara Fancelli’s beauty and her husband’s habit of combing her, the legend of Chiara as the artist’s model and muse would have spread. This is a plausible hypothesis, believed to be so even by distinguished scholars (such as Pietro Scarpellini, who in his 1998 volume on the Collegio del Cambio wrote, in reference to the Virgin who appears in the Nativity fresco, that the model must have been, as with almost all of Pietro’s Madonnas after 1493, Chiara Fancelli, the artist’s wife). It would not be strange that an artist would ask his wife to pose for the figure of the Virgin, and the obvious similarity of so many Perugian Madonnas executed at the turn of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries helps to reinforce this idea. In contrast, however, is the fact that the faces still appear stereotyped and uncharacterized individually, and the absence of any certain news to support this suggestion. Which nevertheless contributes to the fascination with the Madonna of the Confraternity of Consolation and other Madonnas by Perugino.

The article is written as part of “Pills of Perugino,” a project that is part of the initiatives for the dissemination and diffusion of knowledge of the figure and work of Perugino selected by the Promoting Committee of the celebrations for the fifth centenary of the death of the painter Pietro Vannucci known as “il Perugino,” established in 2022 by the Ministry of Culture. The project, edited by the editorial staff of Finestre Sull’Arte, is co-financed with funds made available to the Committee by the Ministry.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.