Speaking of works of art, one would wonder if the consummate question applies, “If a tree falls in the forest and no one hears it, has it made a sound?” Does the completeness of paintings, sculptures or creative products whose vision has remained the preserve of only the author and a few others fail? Can the status of works of art be applied to them despite the fact that no one is aware of them? For sociologist Howard Becker, author of the illuminating text The Worlds of Art, while not dwelling on the aesthetic aspects, the answer is yes. In his book, in fact, he points out that art is a social activity, and therefore “once the work has been made someone must enter into a relationship with it, react to it emotionally or intellectually”: the artist and the work that do not meet society will not be recognized as such. This view, certainly not without logical sense, preferring a functionalist approach has the limitation of putting the mere moment of performance before the formal and poetic characters of the work. After all, can one deny that the hundreds of writings that lay, unpublished and never even shown, in Emily Dickinson’s room, arranged in a binder and found there by her sister, were masterpieces of poetry? And isn’t the same true of those Vivian Maier photos, now become celebrated, whose artistry the far-sighted John Maloof recognized once he came into possession of the negatives by purchasing a batch of items from a box? It would seem, then, that the ancient tree conundrum could be answered in the affirmative, not least because there is always some listening ear in the forest, as the English writer Terry Pratchett argued.

Fortunately, personalities whose entire lives were not enough to make them stand out, and therefore condemned to anonymity, are occasionally being rediscovered, thanks in part to the courage and stubbornness of those who have taken up their legacy. Among them is an outstanding artistic figure, who certainly deserves to be brought to the attention of a public that in his lifetime was precluded from him: the painter Remo Brizzi, and to whose memory, with dedication, his brother Emilio is devoting himself, who stubbornly tries not to let his name and his art fall into oblivion, and who for this reason has given birth to theRemo Brizzi Archive.

The details and some biographical information are the only information we have on this artist. Everything else we have to glean from his works, for Brizzi was throughout his life rather reluctant to discuss his art: “He spoke often of wanting to rehearse, never of setting himself to work consistently, hard and continuously in one direction. Nor did he bother to write, to explain himself, how much more to justify himself,” his brother argues in some memoirs dedicated to the artist. “It was not superficiality, I think, but complete and total, profound modesty, as well as a tendency to desecrate anyone [...] including himself.”

Remo

Remo Remo

Remo Remo

RemoBorn in Ancona in 1958, where his father worked as a neurosurgeon, much of his life was consumed in Emilia Romagna, where moreover he died prematurely in Bentivoglio in 2017. Brizzi was an all-around creative: he showed a flair for painting from an early age, perhaps emulating his father who dabbled with paintbrushes, and at age 13 he painted a nocturnal landscape from life. This already seems to highlight several aspects later developed in his mature painting: an interest in the landscape genre, a predilection for scenes tinged with darkness, brushwork and color giving way to drawing, and a view of the real datum distorted in favor of the search for emotional and dramatic effects, just to list a few.

And although drawing and painting would remain his constant companions, so much so that in the early 1980s he attended the workshop of Folli, a local painter, in Parma, for some reason he took another direction; he graduated from DAMS in Bologna with a thesis on Bauhaus in America, and after varied work experiences, he turned to design, moving to Milan, designing furniture and other objects with sinuous lines, including the Planta lamp, which also found some prominence in trade magazines such as Domus or Casa Vogue. A number of works we know of date from this period, such as the beautiful View of Toledo, painted around 1982. The city that El Greco elected as his home is painted by Brizzi with a certain propensity for synthesis and a sureness in tonal values played on earthy tints, showing tangencies with the painting of Ottone Rosai, albeit preferring a much broader and more airy vision.

But at the end of the 1990s, after some difficulties encountered in his work, he decided to return to Bologna near Porta Lame, a square or rather traffic circle, an iconic place for having been the scene of one of the most important clashes in Italy between partisans and Nazi-fascists. Here, but only by chance, in a large but spartan apartment he gives life to his own personal resistance, that of wanting to become a painter without accepting too many compromises, without giving himself much trouble in that whole sequence, perhaps unbearable also because it takes time away from art but certainly necessary, of practices aimed at selling, exhibiting and being recognized as a professional. He tries sporadically, a few contacts with a few galleries, participation in a handful of group shows and exhibition-markets, rare commissions, but he collects little or nothing, and you never have the encounter with his Félix Fénéon or Clement Greenberg.

Remo

Remo Remo

Remo Remo

Remo Remo

Remo Remo

Remo

That Remo Brizzi was intolerant of these kinds of concessions is also shown by the fact that he spent little time talking about his art, never leaving titles or dates to his works, which he even rarely signed, as his brother writes: “Someone suggested that he sign his works, and he did so using a signature stamp-perhaps to be controversial,” but “the delicate balance of the pictures did not tolerate even that minimal mark, and he was forced to touch them up and erase quite a few.”

Indolence to his self-promotion did not jibe with lack of professionalism or diligence to art: carefully, in fact, he prepared his supports, dark rough canvases or boards on which he spread his imprimitura, usually white chalk on a black background, and so too with the frames, which he colored to go along with the breath of the painting. Like a hermit, he lived in his apartment, set up in many workshops for painting, engraving, technical drawing and carpentry, cultivating his art as a personal affair, finding in landscape what Giorgio Morandi, a few kilometers away from Brizzi’s apartment, found in still lifes (but also in the landscapes themselves): the chosen genre on which to base, to essay, to develop his own pictorial saying. And with the famous Bolognese painter would also return other commonalities as we shall soon see.

Remo Brizzi’s entire artistic parabola seems constantly in search of his pictorial values, following, however, a painstaking attitude that seems to want to start again from the basics. Otherwise, one would not explain his commitment to some drawings and sanguines of great virtuosity and academic attention that have as their subjects Michelangelo’s Battle of the Centaurs, works by Giambologna, and other greats of antiquity, which would have little in common instead on later artistic choices.

The landscape, we said, immediately became his figurative obsession, so much so that it constituted the vast majority of his corpus; with it he seems to find an ideal rather than a physical communion, in fact with the exception of the reality that he merely peered at beyond the window of his apartment, and in this he still reminds us of Morandi with the views of Via Fondazza, he more often found himself experiencing it through photographs, not infrequently taken by his brother, the starting point for his personal compositional exploration. Little remains of the photographic snapshot, however, as Brizzi moves on to dilate, streamline and transfigure it through his own thoughtful elaboration, first in the mind and only later on canvas. With this production he pushes his analytical and meditative study of the formal elements of the painting, ranging between genres and artistic approaches, pursuing an investigation that seems to want to finalize a compromise and synthesis between compositional structure and expressive or poetic content.

Remo

Remo

Remo

Remo

Finding ourselves before works without a secure dating, which can only be partially reconstructed through his brother’s recollections, it would be easy to believe that we can recognize a coherent itinerary, leading from a more solid and descriptive figuration toward a landscape increasingly transcribed with minimal means and a greater tension toward a lyrical abstraction, in a path not unlike many artists. This evolution, although in a sense proven, is also challenged by later works where representation re-emerges with more force. It is then my opinion to affirm that Remo Brizzi certainly started from more modeled images arriving then to a rarefaction of representation, but once he acquired awareness in his tools he made use of this confidence to choose from time to time the register that best suited the landscape to be rendered on canvas, conveying expressive ambitions among the most diverse.

There is a small nucleus of older works, in which the painter takes as his subject city views captured with a wide depth of field. The subjects are monumental urban fabrics, connoted by the presence of towers, Gothic spires, churches and bridges as in the paintings Paris and Antwerp. These umbral landscapes, connoted by a certain descriptive flair and a palette based almost entirely on brown and brown tones, with the exception of small handkerchiefs of faint sky blue, see architecture resurface from misty black backgrounds, gradually becoming more solid from evanescent.

Later, this broad focus on views will end up in the background, toward narrower representations, where the portion of the places depicted are reduced to a few structures and show very different pictorial holdings. Nonetheless, even later landscapes with wide views reappear, such as the Malta painting, with its clarified chromatics, played out between the relationship between greens, yellows and grays, depicting urbanism simplified and almost deprived of its volumetry, like a compact mass, in a dialogue between solids and voids. In addition, emblematic are two rather late landscapes with views of Bologna, including The Towers of Bologna, where the anecdotal and calligraphic brushstrokes of the early works are replaced by a more rapid and gestural one, which, however, does not give up describing and delineating the skyline.

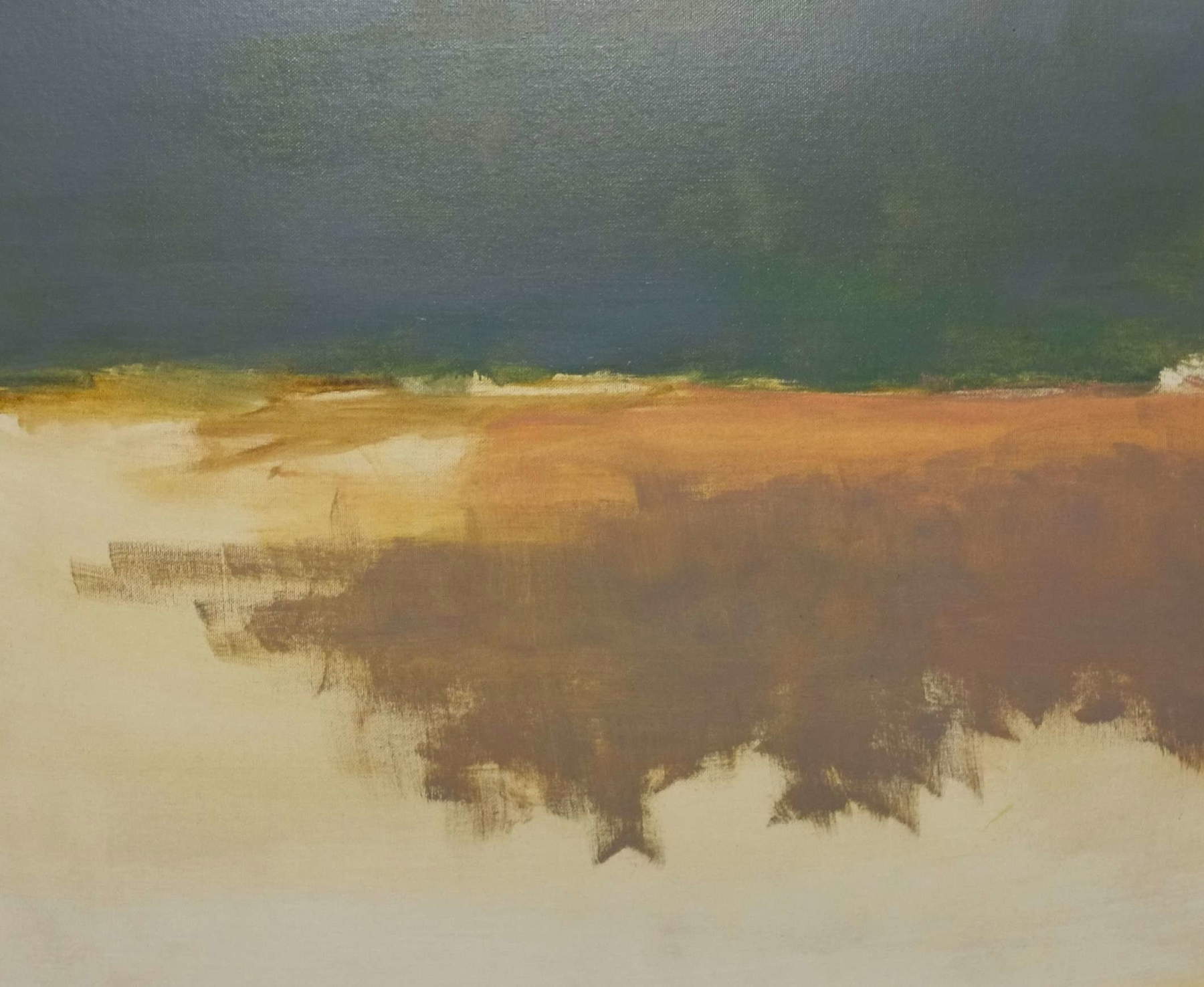

Of great interest in my opinion is also a conspicuous number of works in which it is nature and no longer the work of man that is the privileged subject, such as The Amstel River to Oudekerk, Lake Massaciuccoli and Dunes of the Island of Texel. These are pieces where the definition of space is far more muted, often in subject are river or lake views, in which Brizzi also seems to place interest in the meteorological datum, but perhaps with the sole purpose of expressing invisible qualities of nature. They are cloudy or caliginous views, in thin oil and almost bloodless paint, evoking atmospheres of romantic temperament, recalling to some extent some of Turner’s works.

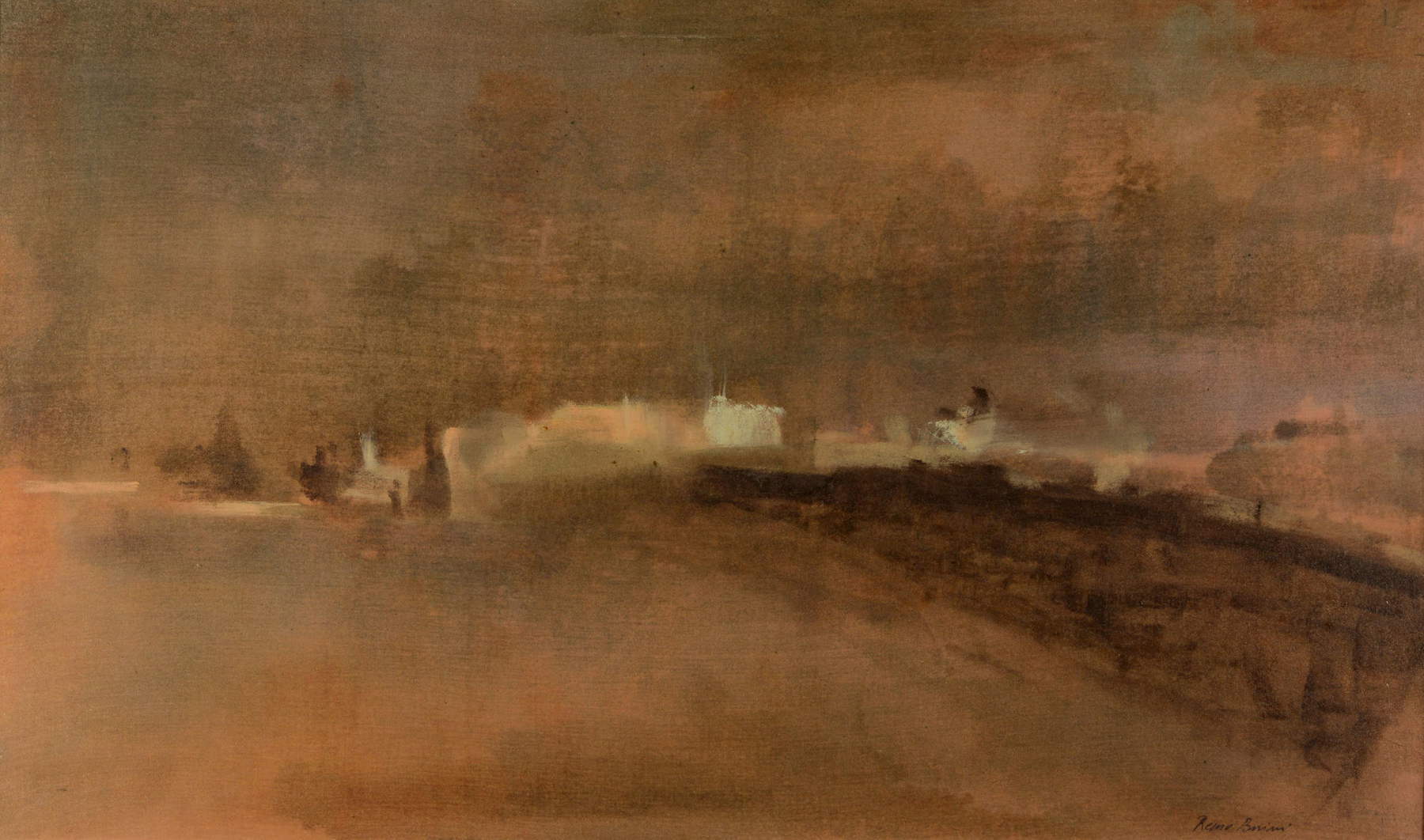

Fruit of this dramatic impressionism are mute and profound places, pervaded by a deafening silence, here the strength lies in a sense of apparent remoteness and detachment that express an emotional contemplation of reality. Among these we like to mention the painting Le Apuane viste dalla Versilia, a painting of which we know the original photograph from which it is taken. The latter shows a double register, the profile of the mountains towering above an industrial aggregate, but Brizzi’s brush only returns the intricate orography and evokes it through dramatic patches of frayed and whimsical color.

Remo

Remo Remo

Remo

Remo

Remo Remo

RemoI then want to dwell on a group of diametrically opposed works, from the framing barricaded around a few elements, Rural Houses of Autan, Bologna View from Home, Canal Grande and Farm in Parma. These are paintings characterized by an interest almost totaled by anthropic visions, and roads, buildings and cottages become the protagonists; they are compositional structures of imposing installations essential in their volumes and serene masses. In these works where polychromy becomes only a mere memory, large portions of raw support are left blank, while a few calibrated strokes are entrusted with the figuration of simplified horizons. Sometimes autonomous and concluded bodies converge and are grafted onto hinted profiles, in a constructive methodology based on the economy of signs and an almost extreme synthesis. Thus, scenes are generated that retain the memory of places, both distant and very close in time, countries of infinite duration, of high meditative intensity, purged here of all emotion, but also tending to the search for a perfect pictorial and compositional balance.

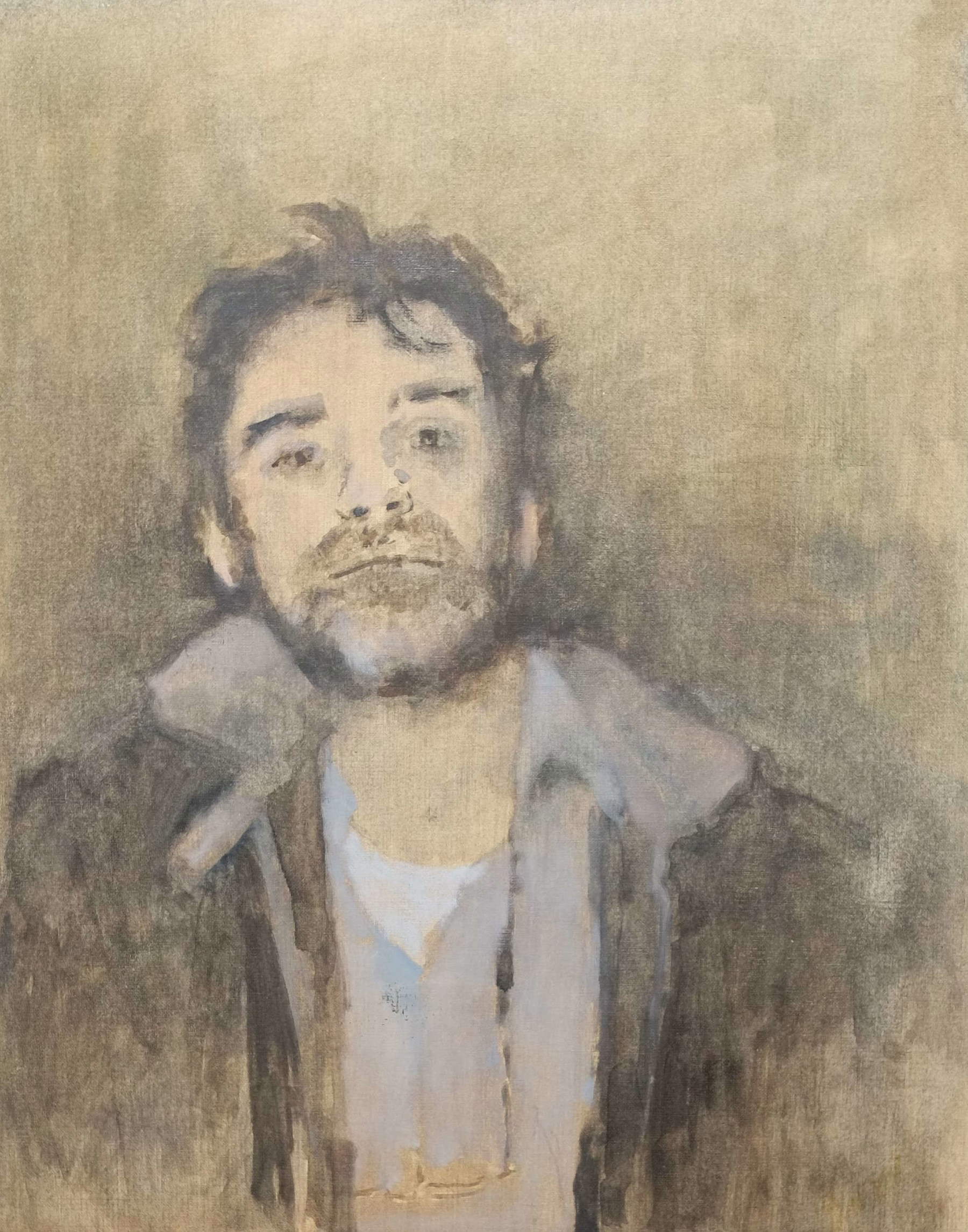

Finally, let us go through what for me constitutes the acme of Brizzi’s production, the pinnacle that perhaps would even have been surpassed if illness had not ended his life. These are works constructed like a melody, through interlocking dowels of limpid and illuminated colors, sometimes more textural and at other times more liquefied, with which buildings deprived of all morphology and placed on a flat surface are given body. This attempt to establish a visible contact through the evocative power of abstract media, the studied concatenation of basic figures almost like a musical score keeping in mind the uneven weight of each color, as seen in the painting Dallo studio (Lame district), tends toward a closeness, though more restrained in chromatics, with the textures that came out of Nicolas De Staël’s brush. This research seems to find a meeting point with the previously presented production, that of free-standing, in the work Landscape (Gaione). On the canvas for the totality almost free burst shapeless backgrounds but with calibrated tonal values. It represents the landscape that has reached the limit of its own form, in a physiognomy that is increasingly inward, so much so that it becomes visceral fact.

This admittedly not brief but inexhaustible treatment of Remo Brizzi’s work certainly has faults; on the one hand, the arbitrariness with which one has wanted, but mainly for narrative and explanatory purposes, to find stylistic nuclei in an artist so adept at unembarrassedly combining such different instances diverse; on the other hand, the unfortunate omission of any reference to the painter’s other experiments in the field of still life and portraiture, in which he also achieved remarkable results, as evidenced by some powerful self-portraits he left us.

This choice can be traced to the fact that I seemed to see in his research aimed at declining the identity of landscape in painting a happy encounter between meditation on the past and the problems of contemporary art. For this and many other reasons, which we have no more time or space to address here, I strongly believe that Remo Brizzi’s artistic experience must necessarily be recovered.

The author of this article: Jacopo Suggi

Nato a Livorno nel 1989, dopo gli studi in storia dell'arte prima a Pisa e poi a Bologna ho avuto svariate esperienze in musei e mostre, dall'arte contemporanea alle grandi tele di Fattori, passando per le stampe giapponesi e toccando fossili e minerali, cercando sempre la maniera migliore di comunicare il nostro straordinario patrimonio. Cresciuto giornalisticamente dentro Finestre sull'Arte, nel 2025 ha vinto il Premio Margutta54 come miglior giornalista d'arte under 40 in Italia.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.