In the guarded silence of a museum, everything seems still. The works stand, motionless, like relics of another time. Visitors skim with their eyes, walk slowly, sometimes read, often photograph. But what happens when something breaks? When one of these seemingly eternal presences breaks? When art, in the most physical and material sense of the word, gives way?

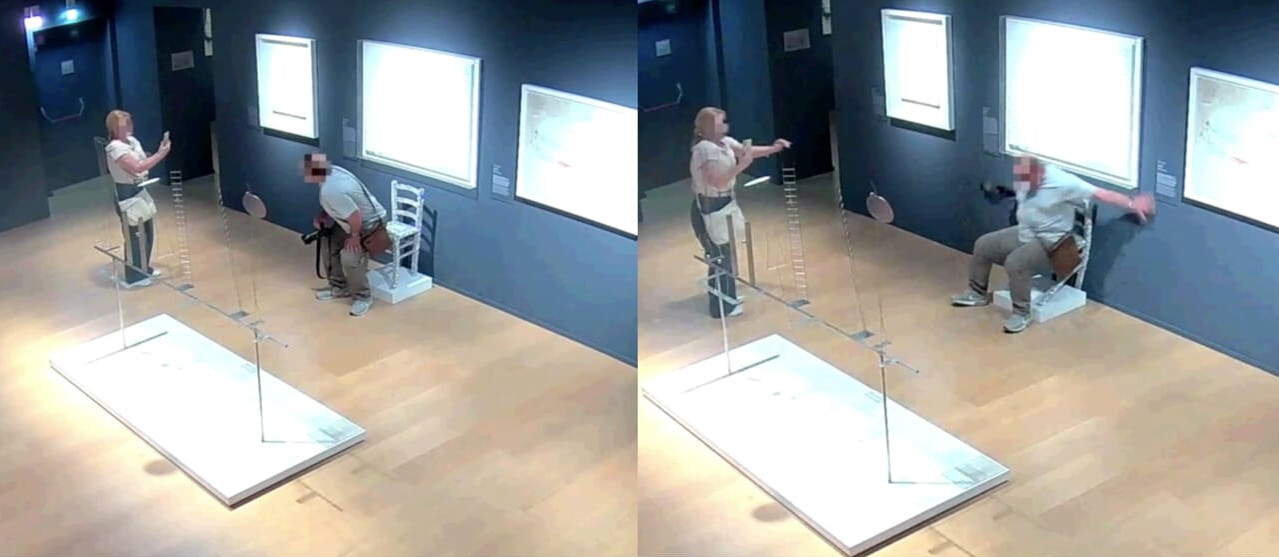

It happens in Verona, at Palazzo Maffei, in the historic heart of the city. A work by Turin-based artist Nicola Bolla, titled Van Gogh Chair, is damaged by a visitor. Not an act of vandalism, not an aggressive gesture: simply, someone sits down. Perhaps to take a photo, to feel part of thework, for an instant of unconscious narcissism. But the chair, built with thin structure and covered with hundreds of Swarovski crystals, is not meant to support the actual weight of a body. It is a sculpture, an idea transformed into form. And under that weight, the work collapses.

The episode made the rounds of the newspapers, bouncing between indignation and irony, with headlines such as “idiot tourist destroys crystal chair” or “work of art mistaken for furniture object.” But behind the curious news lies a deeper question: what is left of a work of art when it is damaged? Is it still itself? Can its function change, and with it its meaning?

In our relationship with art, a paradox exists: we approach it, contemplate it, but often do not understand it. Especially in the case of contemporary art, which plays with the ambiguity between form and function, between object and symbol. A chair can be, at the same time, a piece of furniture and a conceptual sculpture. But it cannot be both at the same time. Nicola Bolla’s chair, part of a series of works that reinterpret everyday objects by covering them with precious materials, is a visual trap, a game of ambiguity. Like many contemporary works, it lives in the short circuit between what it looks like and what it is. Seemingly inviting, shimmering, elegant, reassuring, it is actually unserviceable, fragile, poetic. It is precisely this contradiction that constitutes its meaning: a common object, rendered unserviceable and sacralized by its preciousness. Those who sat in that chair have thus made a cognitive error even before a physical one: they have taken a work for an object, they have confused art with life. And while it is true that art often wants to be experienced, this episode also shows how fragile the line between experience and distraction is.

A question then arises:is a damaged work ofart afinished work of art? Or is it simplya work that changes, that evolves, that opens itself to another narrative? In the case of Bubble’s chair, the answer comes quickly: museum restorers intervene, reassemble the work, reconstruct its form. The artist approves. The institution is reassured. But something, inevitably, has changed forever. And the artist is aware of it.

The chair is no longer “the one from before,” but has become something else: a wounded, reassembled object that carries within itself the memory of the accident. It is now a work that also tells of its vulnerability. A bit like the Japanese kintsugi vases, which show cracks filled with gold to make fragility as beauty explicit. Bolla’s work, even if restored, can no longer be read without thinking about the gesture that damaged it. So much so that he himself is considering changing the title of the work. Its meaning has expanded, layered. It has lost its innocence, but it has gained depth.

Why? Today art is not only an aesthetic production: it is also a relational practice. It lives in the space created between the work and the audience. When this space is violated, by neglect, superficiality, or simple ignorance, the work suddenly finds itself uprooted from its function. The delicate balance between supply and reception breaks down. The Verona episode is not isolated: other recent examples have shown how the fragility of art is also acollective responsibility . It is not enough to put up a “do not touch” sign. We need an education ofthe gaze, a pedagogy of fruition. Looking at a work is not a passive gesture, but a form of care.

And here we touch on anuncomfortable truth : many viewers are no longer used to distinguishing between aesthetic and performance experiences. The social world has cleared the way for the spectacularization of everything: every place is a set, every object a backdrop. But art is not an object for consumption. It is, if anything, a place to be inhabited with respect. There is one aspect, however, in this event that deserves attention: the work is now more telling than before. Before it was just an homage to Van Gogh’s chair, a playful but conceptually limpid sculpture. Now it is also a document of our time. A testimony to cultural fragility. A proof that works of art, like living bodies, can break.

Nicola Bolla’sVan Gogh Chair is today, paradoxically, more significant than before. Because it went through the event, suffered the fall, and emerged transformed. Not just repaired, but carrying a new level of meaning. This does not justify the destructive act, of course. But it does invite us to rethink the meaning of the work not as a static object, but as a living entity. Art is not only representation: it is also relationship, trauma, memory. We live in an age when everything is accelerated, everything is documented, everything is potentially distracted. But art asks for slowness, it asks for attention. And it also calls for responsibility. Not only from those who make it, but also from those who watch it, host it, live it.

Perhaps this is the deeper meaning of the Verona episode: to remind us that art, just like life, is always exposed. It is fragile. It is changeable. But for that very reason, it continues to speak to us. Even when it breaks. And perhaps, on closer inspection, only that which can break is truly alive.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.