Did you know that Caterina Sforza collected health and beauty recipes? Meredith Ray, a professor at the University of Delaware, talks about it in her article published on the Recipes Project site, and Ilaria has translated it for you!Here is the link to the original. Enjoy reading ;)

In this post I will present some tidbits from my recent book Daughters of Alchemy: Women and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy" (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015) [ndt. Daughters of Alchemy: Women and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy]. I drew these insights from the first chapter Caterina Sforzas Experiments with Alchemy and the third chapter Scientific Culture and the Renaissance Querelle des Femmes: Moderata Fonte and Lucrezia Marinella. [ed. The Querelle des Femmes is the dispute over women and men, that is, the relations between the sexes].

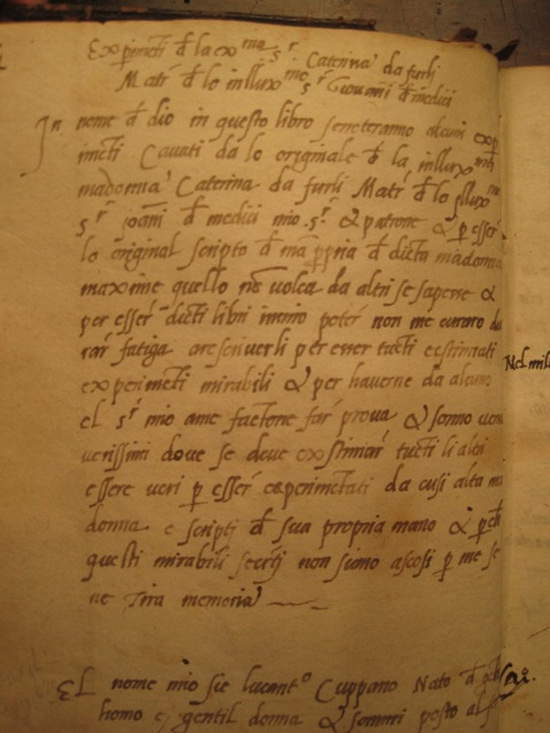

|

| Front page from Caterina Sforza’s Experiments. |

You know that Glamour magazine you were reading at the airport with tips on how to take care of your skin, applying the right make-up, and make you look younger than you are? Those recipes have a much longer history than you may think. Beauty and health recipes were an important element in the scientific culture of the early modern age, when curiosity about nature’s secrets combined with growing enthusiasm for testing and perfecting through experimental techniques.

Caterina Sforza (1463- 1509), lady of Forli and Imola in Romagna and progenitor of the Medici dynasty, is an emblematic example of early modern women who collected recipes.

At the turn of the sixteenth century, Catherine recorded more than four hundred beauty and health recipes as well as a healthy smattering of alchemical formulas in a manuscript entitled Experimenti. The manuscript, still extant in a sixteenth-century transcription made by Lucantonio Cuppano (1507-1557), includes directions on how to prepare lipsticks, lotions, and hair dyes (with a clear preference for blond and red); directions on how to cure illnesses, from fever and migraine to epilepsy and infertility; recipes for increasing libido and recovering virginity [see my article Impotence and Corruption: Sexual Function and Dysfunction in Early Modern Italian Books of Secrets]. Most valuable of all, the instructions for creating the philosopher’s stone and quintessence: the elixir that was thought to cure all diseases, protect against all ills, and prolong youth (perhaps forever).

Take, for example, this recipe for talcum powder water a mineral-based solution produced through distillation, used by early modern alchemists for various purposes that is said to accomplish many of these goals immediately:

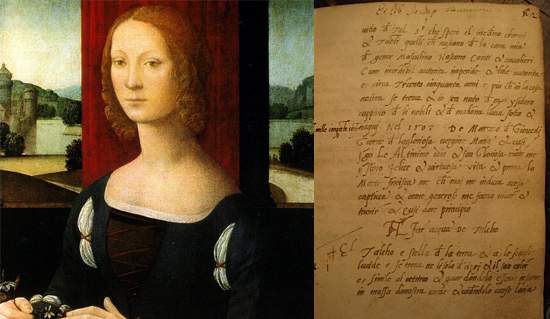

El talcho è stella de la terra et ha le scaglie lucide e se trova ne l’isola di Ciprij et il suo colore è simile al cetrino et guardandolo essendo insieme in massa dimostra verde e vedendolo verso l’aria dimostra come cristallo et ha le infracripte virtù senza le altre che non sonno in libro noctate quale seria el desiderio de li alchimisti saperlo: prima per fare le donne belle e levarsi omni segno o machia del viso de sorte che se una donna de sesanta annij la farà parere de vinti.... yet said water of such or true powder of it who would drink of it in white wine would heal one who would be avenenato et chi in quel giorno ne havesse in vino biancho serà sicuro di veneno et de omni morbo e peste... Ancora se fa mentione che dicta acqua fa de lo argento oro, et de le zoie false le fa perfecte et fine (dagli Experimenti de la Ex[ellentissi]ma S]igno]ra Caterina da Furlj Matre de lo inllux[trissi]mo S[ignor] Giovanni de Medici, in Caterina Sforza, ed. Pier Desiderio Pasolini, v. 3, 617-618, Roma: Loescher, 1893. Cuppano’s sixteenth-century transcription is preserved in a private archive).

Multifaceted recipes like this, inspired by alchemical practice, abounded in early modern scientific culture. They circulated in manuscripts and prints, among men and women, orally and through epistolary, business and court contacts.

|

| Left, Lorenzo di Credi, detail of the Lady of Jasmine, probable portrait of Caterina Sforza (c. 1485-90; Forlì, Musei San Domenico, Pinacoteca Civica); right, the page of Experimenti with the recipe for talcum powder water. |

Privileging direct experience, observation and application over study or theoretical teaching, the recipes published in Caterina Sforza’s Experimenti reflect the empirical and heterogeneous character of early modern science. Like the printed books of secrets that would achieve enormous popularity in the early sixteenth century (described in William Eamon’s Science and the Secrets of Nature [La Scienza e i Segreti della Natura] , Catherine’s manuscript oscillates between alchemy and medicine, the royal and the occult, the home and the court. Her search for secrets was not only recorded in her manuscript, which she bequeathed to her son (the condottiere Giovanni dalle Bande Nere, father of Cosimo I de’ Medici). He also dealt with this in letters to his pharmacist, spies, family members, and other alchemy enthusiasts throughout Italy.

The Sforza’s activity counts her at the origins of a Medici interest in alchemy and experiments that would expand well into the seventeenth century, placing her within the broader panorama of women’s scientific activity in the early modern age. She was not alone in this activity: women’s engagement with scientific culture was wide and varied, and the language of recipes proved useful in multiple contexts, including the Renaissance debate about women. During the 1600s, Moderata Fonte, in her dialogue The Merit of Women, would contrast the efficacy and honesty of some medical and cosmetic recipes capable of curing disease or transforming appearance with the impossible task of finding a recipe to teach men to respect and consider women their equals.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.