Entitled Expositiones in librum primum Regum is a problematic book of biblical exegesis (i.e., a commentary on a content of the Bible: in this case, on the first book of Kings) of which we know of only one manuscript witness, preserved at the State Library of the Badia National Monument in Cava de’ Tirreni. Indeed, because of its importance and connection of the territory, it could be said that this precious codex represents perhaps the most symbolic work in the library. We know of no other manuscript versions of this work, which prior to 1933, the year in which the Cava codex was discovered, was known only from theeditio princeps (the first printed edition), published in Venice in 1537 by the publisher Bernardino Stagnino (we do not know, however, which codex he drew from). The Expositiones were believed to be the work of St. Gregory the Great, and this was on the basis of an epistle that is part of the Registrum of Gregory the Great’s approximately 850 pontifical epistles, covering the entire period of his pontificate, from 590 to 604. Today, however, the work is attributed to a local monk, Pietro di Cava, known as Divinacello, who lived in the 12th century. To understand all the steps in the story, however, it is necessary to go back to 1933, the year the Cava Codex was discovered.

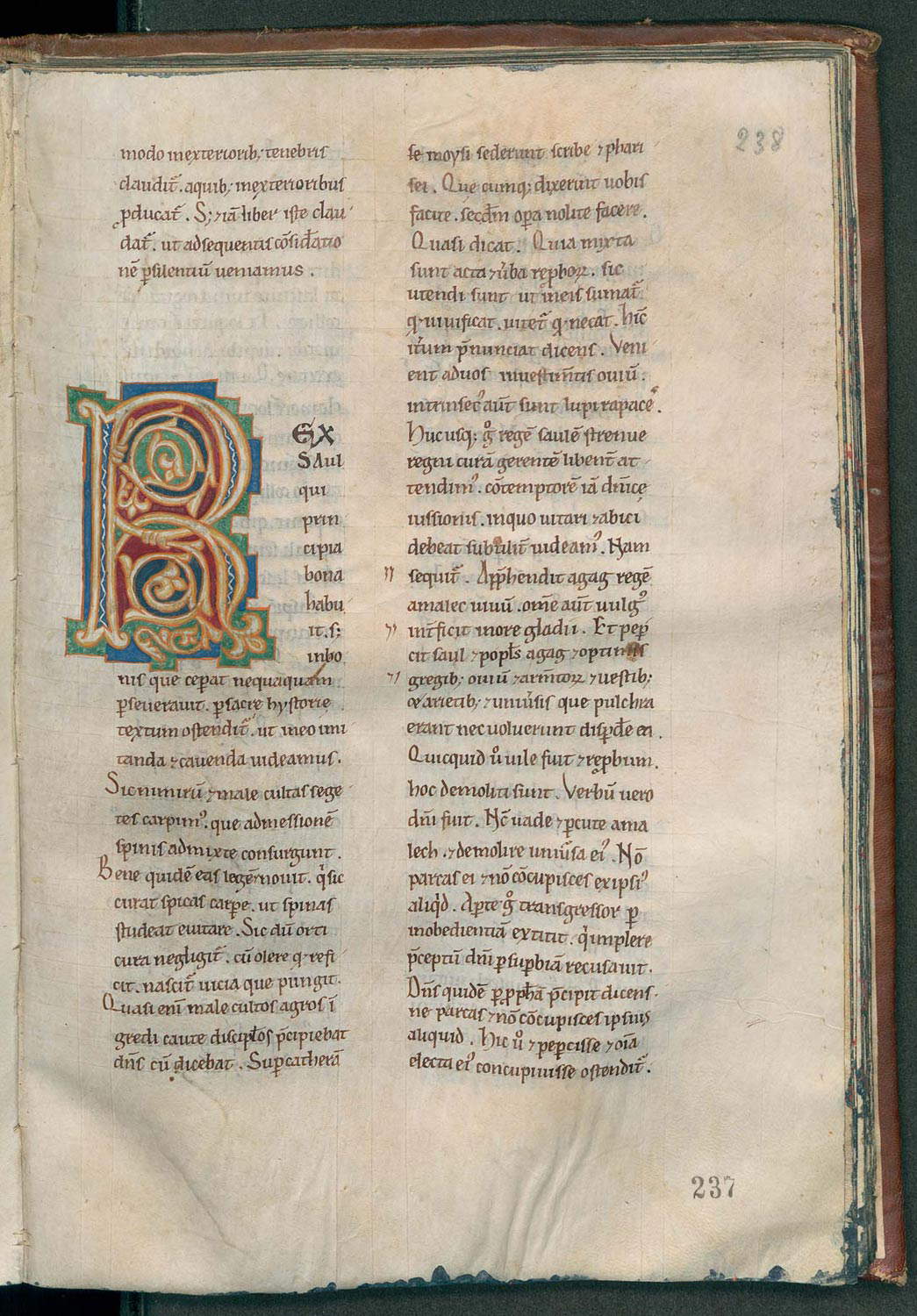

That year, the archivist of the Abbey of Cava, Leone Mattei Ceresoli, was preparing the catalog of the Library’s medieval manuscripts and had been attracted by a codex with an eighteenth-century morocco binding, on the spine of which was the title Moralium S. Gregorii in Iob pars IV: it was the book that contained the Expositiones. “This news,” the archivist wrote, “may be pleasing to scholars, as no manuscript of the entire work is known at present. It is a beautiful specimen in strong vellum, very well preserved, in Latin script of the late eleventh or early twelfth century. It consists of 269 sheets, measuring mm. 330x324 in two columns of 34 lines each, mm. 65 wide and mm. 240 high with mm. 20 between each. There are illuminated only the initials at the beginning of each of the six books; the one from the first book is missing, because the first quaternion is lost; in compensation there is an illuminated initial at chapter 2 of the first book, but smaller than the others. The writer was one, wrote very sharply and more or less keeping almost always the same way, only towards the middle for many sheets the letters tend to enlarge and space out.” Mattei Ceresoli, studying the codex, noted that a corrector contemporary with the copyist who wrote the work noticed that some words and entire propositions were missing, and therefore thought to fill in the gaps by inserting in the margin what was missing. He then noticed that the same hand marked in the margin the words from the Rule of St. Benedict quoted by St. Gregory the Great: this is the only link between the figure of the pontiff who lived in the 6th century and the Cava manuscript. However, no element in the manuscript appeared decisive to cast doubt on the attribution to St. Gregory the Great.

The solution came in 1985, when scholar Hubert Houben published some unpublished fragments of the Chronicon Venusinum, a 12th-century chronicle relating to the city of Venosa, as part of a dedicated work. In the newly discovered fragments, it could be read that Pope Innocent II ordered the abbot of Cava to send twelve monks “optime instructis et omnem experientiam habentibus de cenobii regimine et regulari observantia,” or “excellently instructed and richly experienced in the life of the coenoby and the observance of the rule,” to the abbey of Venosa, which was then in a serious state of decay. The abbot of Cava, Simeon, chose as abbot of Venosa the monk Pietro known as Divinacello. And again in the Chronicon Venusinum there is mention of Peter’s personality, described as an extremely intelligent person in both temporal and spiritual affairs and as a great connoisseur of divine human laws, and it is further specified that a few years before he became abbot of Venosa he had written a very learned commentary on the Books of Kings up to the royal anointing of David.

The fact that many elements led to the unfounded attribution to Gregory the Great (first realized by the scholar Adalbert De Vogüé: the absence of a dedicatee, strange for the pontiff, the lack of references to other writings of the author, the absence of reproductions of excerpts from other works), and the coincidences on dates and roles thus allowed the attribution to Peter of Cava, first formulated by De Vogüé himself. Moreover, the discovery of the connection between Peter and the commentary on the Book of Kings, wrote Guido Innocent Gargano, “added [...] to the observation of the absolute rarity, not to say silence, of any reference to this supposed work of Gregory by all medieval writers up to the 12th century, as well as the paucity of manuscripts, just two, dated in the same period and coming from the monastery of Cava de’ Tirreni, where, as it happens, Peter II had grown up as a monk, before being sent to Venosa.” In short, the question of authorship seems to have been clarified, although it has also been suggested that Peter may have reworked, for his commentary, texts from the Gregorian era.

In introducing his treatment, Peter explains that he intends to proceed with the study of the work without choosing passages to explain to the faithful, but he will explain the first Book of Kings book from the beginning up to the episode of David’s royal anointing. “The limit set,” wrote scholar Dante Sergius, “serves Peter Divinacello to ascertain whether, as a function of the brevity of the work, it will be appropriate to extend the commentary to the entire First Book of Kings, with an awareness of the risks associated with the ambition to do.” This is because commentary on the sacred word is a rather difficult operation, since for the author of the Expositiones, Sacred Scripture is like a forest: “Placed on high [the commentator, ed.], although with a keen gaze he scans the immensity of the forest, nevertheless, while he glimpses the peaks of the mountains, the ridges of the hills, the tops of the trees, all at one and the same level, he does not notice the deep valleys and the vast plains that remain hidden in the intervals. But if he sets out to traverse this space that seemed small to him, he finds that far from having seen everything, as he thought he had, he is left with much more that he has not seen.” The idea of commenting on the first Book of Kings meets the need for everyone to understand the biblical text, which is why Peter of Cava also chooses clear and understandable language for his exposition. And the importance of the first Book of Kings is also emphasized: “Since the beginning of this book contains the mysteries of the holy Church and at the same time presents us with the moral behavior of the righteous man who strives to follow the right way, my explanation follows both directions, and so the actions of the ancients, while they make known to us the reasons for the new faith, help to guide our conduct. And since in the way of salvation faith precedes works, we premise the typical interpretation as a solid foundation, to which the whole edifice of the work we undertake is superimposed and follows, in its moral and historical explanation.”

In his exegesis of the sacred text, Peter of Cava focuses on some particular aspects, well outlined by Dante Sergius: fruitfulness as the culmination of contemplation; overcoming the opposition between contemplative and active life; the concept of the monk as a “unified man”; openness to secular culture; and the non-conversion of the Jews. On fruitfulness, Peter, commenting on the passage in the Book of Kings in which Anna gives birth to the prophet Samuel, asserts that the gift of motherhood comes from God, and is received by the soul in the midst of contemplation, in the vision of heavenly light (in Peter’s vision, concepitre means “to enjoy the ineffable joy of the supreme contemplation of God Almighty; to give birth means not being able to conceal the signs of charity conceived in the soul”). By making himself the bearer of this thesis, Guido Innocenzo Galgano observed, Peter of Cava “not only eliminates at the root any opposition between the active life and the contemplative life, but also recalls, with extreme rigor, the indispensable circularity, in the line of a true motus perpetuus, in which active life and contemplative life alternate, with the elimination of any hierarchical type of discourse between the two forms of life, one and the other being oriented necessarily to that charity which opens to the exaltation, with authentic praise, of the one who ineffably loves.”

The concept of the monk as a “unified man” is meant to be a teaching that Peter of Cava derives from the person of Christ himself: according to the author of the Expositiones, the unified man is the one who desires to see the face of God in heaven and on earth (“The monk, who has renounced the world, ardently aspires to the vision of his Creator, inasmuch as he visibly bears on his forehead the sublime splendor in which he must always find his own identity, is the example of the unified man”), and this concept represents one of the most innovative points of his commentary on the Expositiones. Another very innovative element is the ncessity, according to Peter of Cava, of an in-depth knowledge of pagan culture: the author discusses this topic by commenting, in the book, on the relations between Israelites and Philistines. The “culture of profane books, though in itself it does not serve the spiritual conflict of the saints,” Peter writes, “if it is united with divine Scripture, we obtain from the science of Scripture itself a deeper formation. To this one end the liberal arts are to be learned, in order to understand more deeply, by their training, the word of God. Evil spirits take away from the hearts of some the desire to learn, so that, ignorant of the things of the age, they do not come to a deeper understanding of spiritual realities.”

Peter of Cava’s openness to pagan culture, Sergius pointed out, could derive from the fact that the monks of Cava entertained relations “with the peoples who looked out over the basin of the Mediterranean Sea, thanks to the maritime traffic of their vessels and also to their continuous contacts with the nearby maritime republic of Amalfi,” plus Greeks, Jews and Arabs lived in the lands administered by the Abbey of Cava: openness to new cultures was thus experienced as a necessity, for harmonious coexistence and openness to new experiences. Finally, the Expositiones deal with the complex issue of the Jews’ failure to convert, considering it a part of the divine plan, as St. Paul had already suggested in his letter to the Romans: “the hardening of a part of Israel is taking place until all the nations have entered. Then Israel will be saved as it is written, Out of Zion shall come forth the Deliverer, he shall take away ungodliness from Jacob. This will be my covenant with them when I destroy their sins.”

This is the Library of the Abbey of Cava de’ Tirreni, and it originated in the 11th century: it was established, like all monastic libraries, to provide books for the monks, as provided for in the Rule of St. Benedict. In addition, the Abbey of Cava also had a Scriptorium, in which books necessary for the training of the monks of Cava and the numerous dependent monasteries were written: evidence of this are Codices No. 9 (from the 12th century), Expositiones attributed to the monk Pietro di Cava, No. 18 (from the 13th century), De septem sigillis, and others. The Library was increased in the 14th century, and several purchases for writing materials and book bindings, which unfortunately have not reached us, date from the same century. According to the archivist Leone Mattei Cerasoli, at the beginning of the fifteenth century there began to be a dispersion of the books collected in the early centuries, perhaps because of the passion for books nurtured by some commendatory cardinal, or because of the precarious situation that made the modest number of surviving monks consider so many books unnecessary. Nevertheless, purchases continued: well-wishers of the library proved to be the monks of Santa Giustina (on many incunabula is noted the purchase made in Venice precisely for Cava), Abbot Vittorino Manso (who safeguarded the integrity of the library by obtaining in 1595 from Pope Clement VIII a bull forbidding the removal of books from the library under threat of excommunication), Abbot Filippo De Pace. In 1796 a ruinous landslide detached from the mountain above devastated the Library: the tragic event resulted in the loss of many books and manuscripts.

In the 19th century, after the suppressions of religious orders (first those of 1807 by the King of Naples, Joseph Bonaparte, and then those of 1866 by King Victor Emmanuel II), the library was nationalized, although the abbot remained in charge of the collections and some monks remained as custodians. The monks, however, continued to manage and preserve the library holdings. Today the library has 15,000 parchments, 430 volume manuscripts, 25,000 loose manuscript documents, 120 incunabula, 1,663 cinquecentine, 77,500 printed volumes and 197 journal titles of which 86 are current.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.