LOriente as a mental construct of Europe has always been identified and seen as a mysterious and distant territory, ancient and wild. This construct had very blurred geographic boundaries, which Europeans pushed farther and farther as new geographic discoveries and trade routes progressed. The term Orient, which often included a vision of all that is different and exotic, could mean Turkey, as well as Morocco, Egypt, all the way to Syria or China.

This is a reality that has always been seen in dualism with the West, and indeed, has been foundational to the identity definition of Europe, which in confrontation with those different cultures recognizes itself as a whole. No wonder then, that this indefinite and vast territory, viewed with hostility and fear, has become, for Western culture, the ideal theater of mysterious, exotic and terrible stories and legends, from the myths born around the conquests of Alexander the Great in India, to the phantasmagorical tales of Marco Polo, to medieval bestiaries. And when these lands, even the most remote, ceased to be unreachable and opened up to Western travelers, European perceptions transfigured by myths and preconceptions were so well-established that even in the 19th and 20th centuries a fairy-tale vision of the Orient persisted. Easy evidence of this complex imagery can be found in literature from Baudelaire to Flaubert, as well as in music with Mozart’s The Rape of the Seraglio for example, but even painting is not exempt from Oriental fascination, which indeed imposes itself on several occasions and with different styles and interests over the centuries, posing as a medium for conveying the appetites and erotic dreams that the West placed on Oriental women and their customs. It happened, therefore, that in the nineteenth century, coinciding with a long season where love for the lesotico and theOrient came back into vogue, fostered by the new Napoleonic campaigns, archaeological discoveries, and colonial missions, the imaginary about theOrient was deprived of figures of monsters and other oddities to consolidate instead a repertoire linked to the evasion from the constraints of bourgeois good living: an imagery of sexual reverie, attacks on inhibitions, studded with places and environments devoted to perdition, sinful and forbidden atmospheres. Larte and painting welcomed these subjects poised between eroticism and exoticism, with the favor of wealthy patrons.

Incidentally, curiously, art history already records an illustrious precedent between encounters between a Western painter and erotic subjects set in the East: it is the adventure of Gentile Bellini, who arrived in Istanbul in 1479 and apparently painted erotic scenes for the sultan’s lharem, currently unknown. The first to rekindle such interest in painting were French painters, not surprisingly the most active in the exploration of the Middle East and North Africa. Ingres famously painted several paintings of erotic-exotic subjects, including the painting Odalisque with the Slave Girl in 1842, which became a famous model for works of oriental erotic temperaments, and Turkish Bath purchased by Prince Napoleon in 1862. The same subjects were also frequented by great artists such as Delacroix, Gérôme and the Pre-Raphaelite William Holman Hunt.

In Italy such a genre was most likely initiated by the Romantic painter Francesco Hayez (Venice, 1781 Milan, 1882). The Venetian began as early as the 1820s to paint his sensuous and polished odalisques, sometimes as autonomous subjects of oriental women, others as Old Testament characters inferred with a romantic verve. The iconographic success of these pieces prompted many other painters to imitate him, with a fashion that initially took hold mainly in northern Italy.

The theme of the odalisque perfectly combined the need to secure market favor with the intention of exhibiting one’s skill in the genre of invention and portraiture, and it soon became firmly established in Western imagery. The term odalisque, a derivation from the French word odalisque, itself a transposition from the Turkish o?aliq, identifies a maid or servant. Thus odalisques were the slaves that the sultan placed in the service of his wives and concubines, and they assumed the role of personal maids; therefore, the fact that they were rendered in painting half-naked is improper, as is replacing the term with that of concubine. To get an idea of how such Western preconceptions became ingrained in society, one need only consider that even today these terms are interchanged, and still evoke a sense of exotic and tribal beauty.

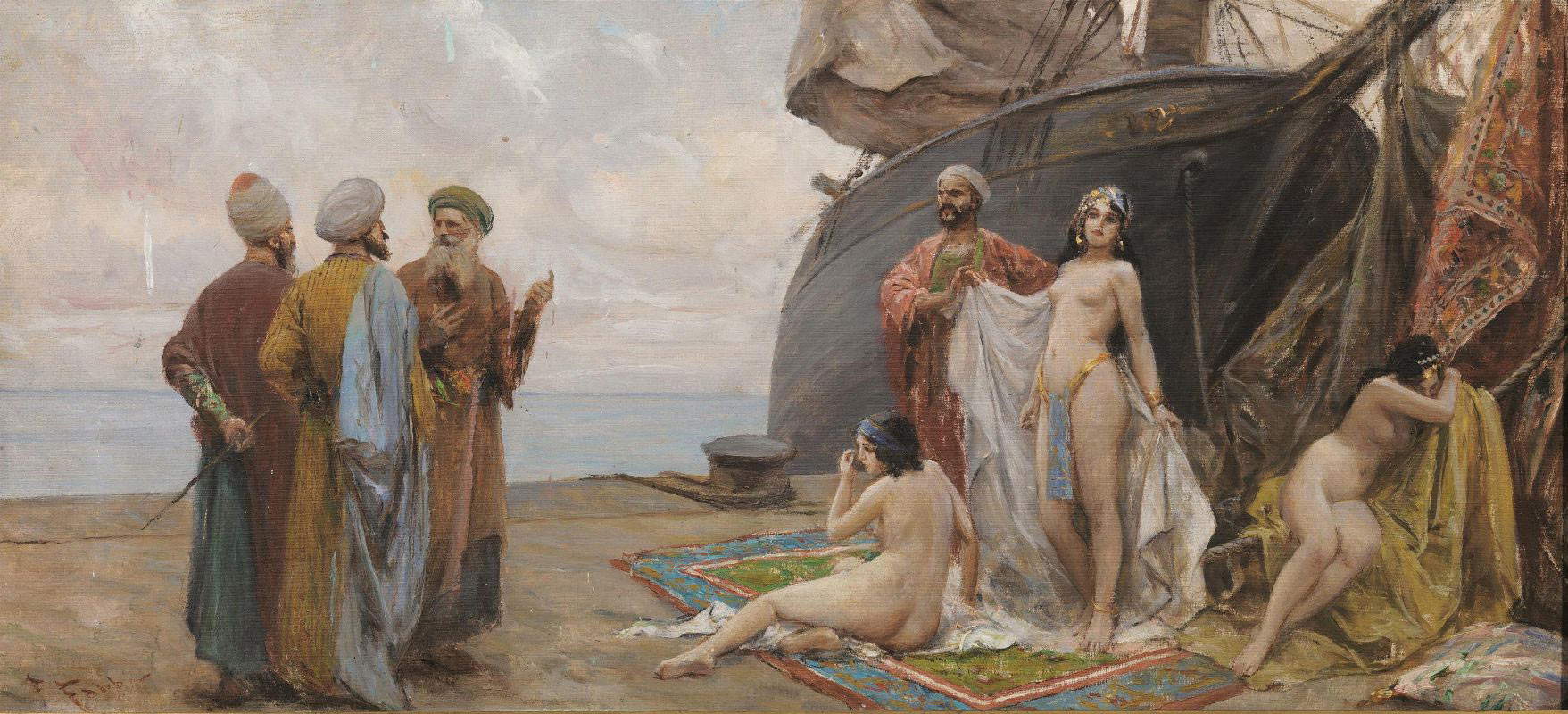

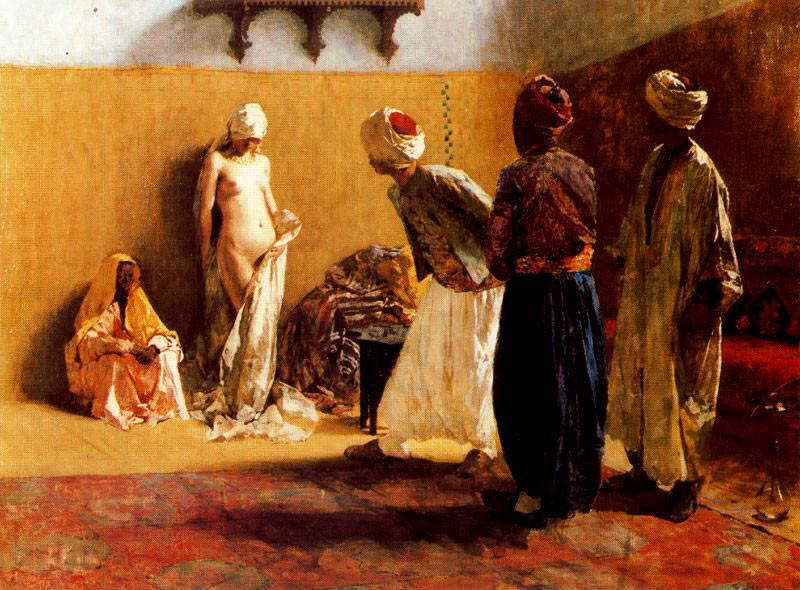

The subject of the odalisque therefore became a pretext for showcasing the imagined Orient, with its load of erotic allusions. An example of this is the painting by Pasquale Celommi (Montepagano, 1851 Roseto degli Abruzzi, 1928), where all the details concur to evoke that Western imagery now so well established. Fuelling the stereotype, the woman is depicted half-naked lying on a ottoman, surrounded by veils, curtains, fabrics, palms, a hookah in the foreground, and holding a fan while sporting a provocative gaze. It is evident that such passages were inferred from fantasy rather than from actual episodes and settings, and in fact many of these painters knew theOrient only through stories. More faithful to the truth, at least in the settings and customs, is The Slave Market by the Bolognese Fabio Fabbi (Bologna, 1861 1946), where a young woman is stripped by her own slaver, who attempts to bamboozle some possible buyers. The allusive meaning of a woman completely at the mercy of the man must evidently have been very successful, if the painter repeated the subject several times. The Messina-born Ettore Cercone (Messina, 1850 Sorrento, 1896) also won numerous praise from collectors with the 1890 lEsamedella schiava>(Examination ofthe Slave Girl), a piece of voyeuristic taste.

The iconographic subject of theodalisque soon rose to success. Between the 1840s and 1850s in the Promotrici of Turin, disturbing odalisques, by Paolo Emilio Morgari, Domenico Scattola and Natale Schiavoni, were exhibited. The 1877 Naples National Exhibition testifies to the liking of southern patrons as well: in fact, several works were exhibited here with the image of the woman represented servile and submissive ready to fulfill all the appetites of the sultan (in whom the collector evidently mirrored himself). On display here was the marble sculpture by the Piedmontese Giacomo Ginotti (Cravagliana, 1845 Turin 1897), Lemancipation of Slavery, which, after being purchased by Victor Emmanuel II, was a great market success, being replicated in numerous copies. The fortune was mainly due to the marble’s strong erotic charge: in fact, as the painter Netti noted, “the marble has an extremely fleshy surface in the naked parts, to the point of being, so to speak, colored.” A different reading of the subject was given by another Piedmontese sculptor, Alessandro Rondoni, with Sira, “one of those slaves who were wounded by their masters with stilettos, when they did not satisfy their whim,” wrote Costantino Abbatecola.

In addition to the representation of women, the erotic theme also finds fulfillment in large compo siations, which have as their privileged theater places that exert an irresistible fascination for Westerners, such as harems and hammams or Turkish baths. These places become caskets of an exotic and inaccessible female world, the scene of intrigue and betrayal. They also lend themselves to the depiction of naked female bodies, with languid and provocative poses and atmospheres. Although lharem generally singles out rooms in the Islamic home reserved for women and children, inaccessible to men, where the erotic dimension is only one of the functions, for the Westerner it takes on the value of a place of lust and fulfillment of the master’s sexual fantasies. The scenes evoked here speak of a fairy-tale Orient, where the painters linger on narrative and sensory details, from the soft and sensual female forms, to the sumptuous colored silks whose rustling we seem to be able to hear, to the intoxicating smells. Often the painters abandon the philological and documentary bent, contenting themselves with evoking a decorative and fantastic Orient, apt to satisfy Western limmaginary, still strongly based on myth, such as that drawn from the oriental tales of the Thousand and One Nights.

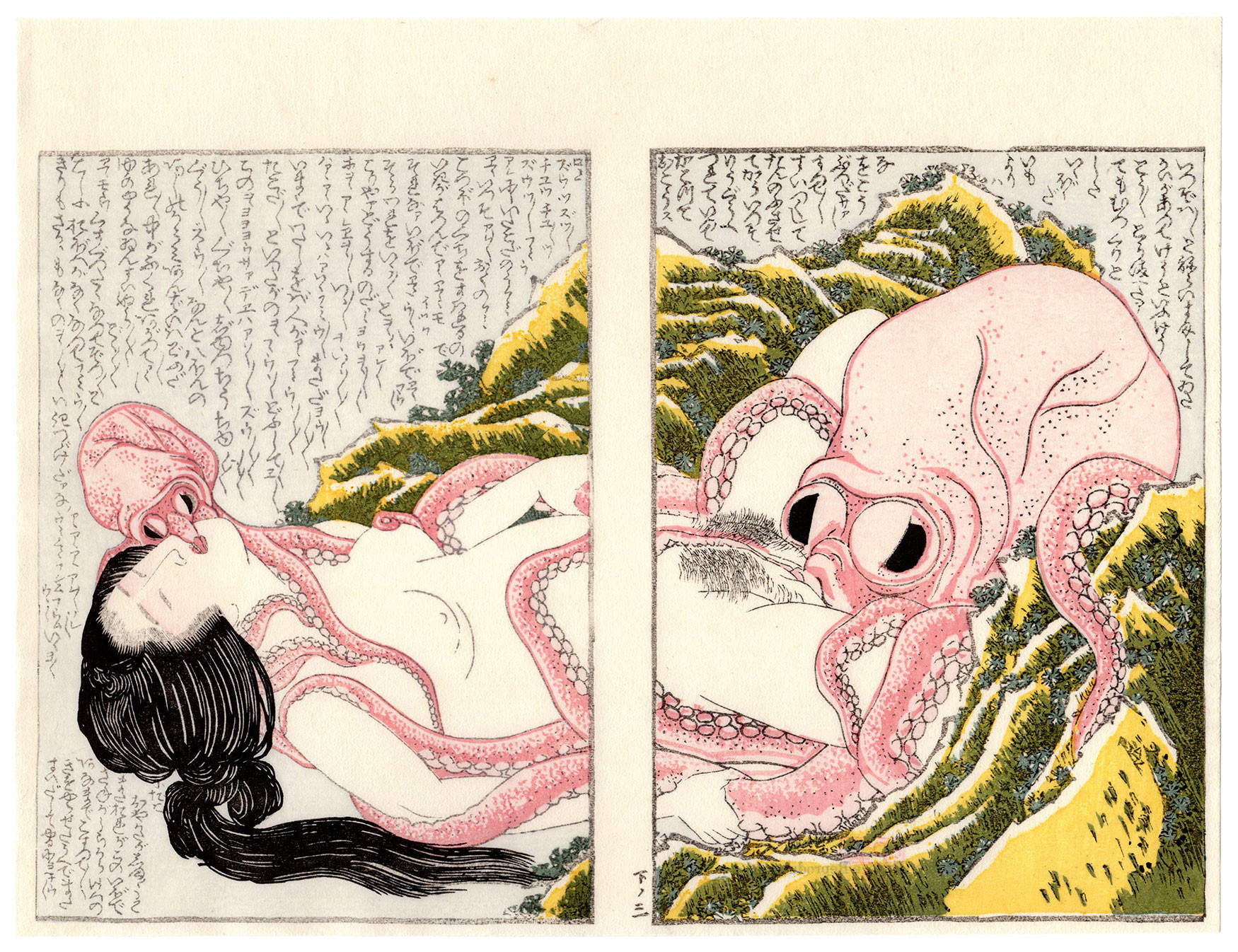

The Neapolitan Vincenzo Marinelli (San Martino dAgri, 1819 Naples, 1892) painted in 1862 Il Ballo dellape nellharem (The Dance of the Bee in the Harem), where the sultan’s dancers dance pretending to have been stung by ape until they undress, a probable reference to international literature and especially Flaubert: “Kuchuk dances us the dance of the bee [ ] we have put over the child’s eyes a little black veil, and we have lowered over the old musician’s eyes a band of his blue turban. Kuchuk stripped herself dancing.” The Nellharem compositions, as well as the Turkish baths, lent themselves perfectly to offering the Westerner a sampling of oriental beauties, frequently nude, as is the case in Domenico Morelli’s painting, where the various exotic beauties are painted with voluptuous and vibrant rendering of drawing and chiaroscuro that make the piece seem suspended in a dream. Although in quite different forms and measures, the interest in the Far East was also often tinged with erotic and hedonistic intonations. The geisha, for that matter, for the Westerner became the transposition of the odalisque, still in the sense of slave and concubine. Western painting could also draw on iconographic models that already belonged to Japanese culture, such as erotic shunga prints. In the opera Fluttuante by Renato Natali (Livorno, 1883 1979), albeit with a more symbolist declination and recalling the theme of death, a reinterpretation of Hokusai’s famous print, Fisherman of awabi and octopuses, appears evident. Western sexual appetites on the beauties of the Rising Sun were also eternalized in music by operas such as Pietro Mascagni’s Iris or Giacomo Puccini’s Madama Butterfly. Limmaginary of wild and uninhibited sexuality was further enriched by Italian colonial adventures in African lands in the late 19th century and during Fascism.

Leroticism was transmogrified onto African beauties, and the works of Italian painters and sculptors were filled with black faces. One example is Angiolo Vannetti’s (Livorno, 1881 Florence, 1962) fountain in Tripoli, recently destroyed at the hands of probably Islamic fundamentalists, but of which a bronze statuette at the Fattori Museum in Livorno, The Two Gazelles, is preserved. Lartista depicted an indigenous woman embraced by a gazelle, which as the sculptor stated “synthesizes the nature of the colony: a young Arab girl softly seated caressing a gazelle: the two gentlest creatures of that land who have kindred between them docile, as much as wild nature.” THE Orient, in its variations, has continued to exert an irresistible fascination for Europeans, entering Western homes through art and literature. The beauties and customs of distant countries have long stood as a refuge from the oppressive limitations of a bourgeois and moralistic society, going on to nurture a myth, the ramifications of which can still be glimpsed today.

The author of this article: Jacopo Suggi

Nato a Livorno nel 1989, dopo gli studi in storia dell'arte prima a Pisa e poi a Bologna ho avuto svariate esperienze in musei e mostre, dall'arte contemporanea alle grandi tele di Fattori, passando per le stampe giapponesi e toccando fossili e minerali, cercando sempre la maniera migliore di comunicare il nostro straordinario patrimonio. Cresciuto giornalisticamente dentro Finestre sull'Arte, nel 2025 ha vinto il Premio Margutta54 come miglior giornalista d'arte under 40 in Italia.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.