San Quirico d’Orcia, 1941: a young Federico Zeri (Rome, 1921 - Mentana, 1998) was called to arms during World War II and sent to Florence, in the light artillery. For the future art historian, the wartime experience ended up becoming a time of great difficulty and inner suffering: in an interview, he would later declare that he shared “none of the ends or ’ideals’ that were supposed to justify the war,” even though he was bound, like so many other young men in spite of themselves, to suffer the consequences of the madness that destroyed the Europe of the time. “I entered into a sort of crisis of abasement, became very thin and fell ill with pleurisy, which was badly treated.” Zeri was first cared for at the hospital in Florence, then he was transferred to the small village in the Val d’Orcia: in particular, he was made to stay in the local Palazzo Chigi Zondadari. The rooms of the palace, the scholar still recounted, “were filled with straw and inside everything was still intact with leaded glass, the walls made of compressed leather from Cordova. I remember there were also paintings and furniture. And the most curious fact was that no one stole, no one took away even a pin, although the palace was open to everyone.”

Palazzo Chigi Zondadari stands right next to the Collegiate Church of San Quirico d’Orcia, dedicated to Saints Quirico and Giulitta: it is an all in all well-preserved Romanesque-Gothic church, despite the renovations it has undergone over the centuries and the damage that occurred during the World War. It was within the walls of the church that the encounter took place that would mark Federico Zeri forever and be decisive in his choice of the course of study that would lead him to become an art historian. It was here, in this hamlet in the hills of Tuscany, that the young man, then a botany student, met the work that would determine the abandonment of the path he had taken up to that point and the beginning of a path that would make him one of the greatest art history scholars ever. “Next to the palace where we slept on straw, on the ground,” the scholar told the microphones of a RAI documentary, "there was the Collegiate Church of San Quirico d’Orcia. And there I saw a work of art that shocked me, and that is still there, fortunately. It is the inlays of the choir executed for the Cathedral of Siena by Barili, and which then, disassembled, was dispersed, and it seems to me that seven pieces stand today in San Quirico d’Orcia."

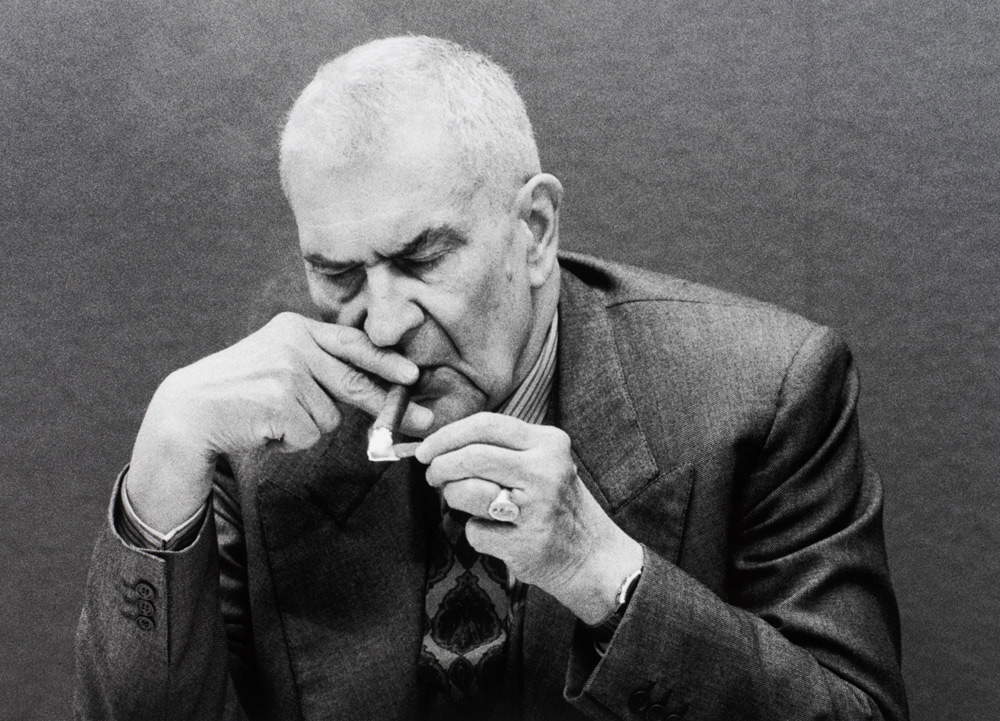

|

| Federico Zeri photographed by Gianni Berengo Gardin in 1988 |

|

| San Quirico d’Orcia: the collegiate church of Santi Quirico e Giulitta and, to the side, Palazzo Chigi Zondadari |

|

| The high altar of the collegiate church of San Quirico d’Orcia. |

|

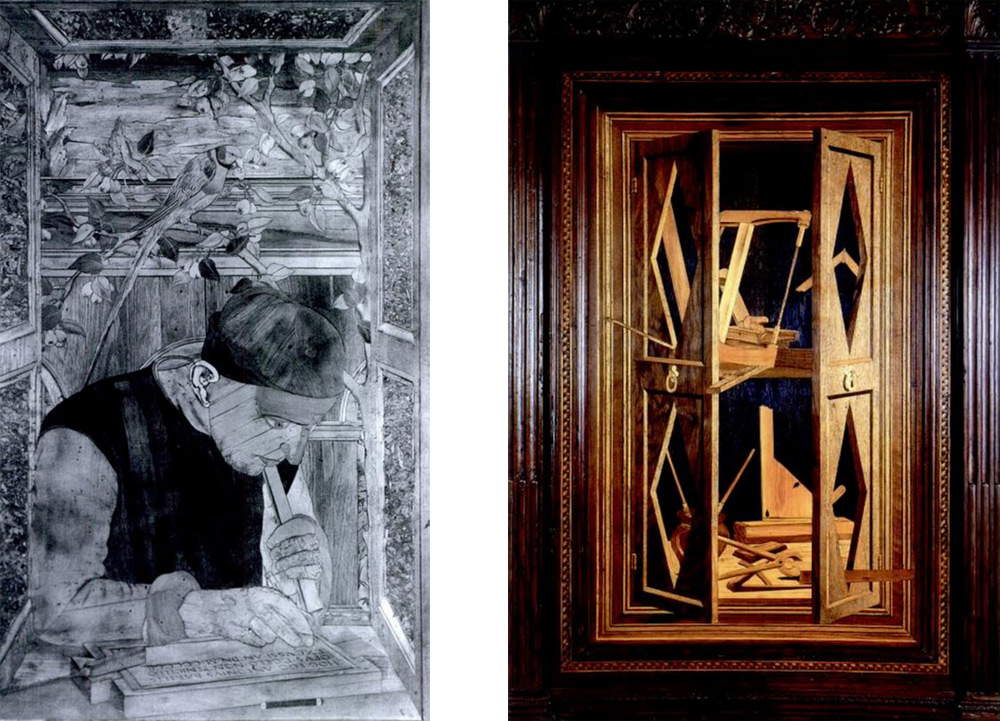

| Antonio Barili, Wooden Choir (1483-1504; San Quirico d’Orcia, Collegiate Church of Saints Quirico and Giulitta) |

The work that upsets Federico Zeri, the wooden choir stalls made for the Sienese cathedral by Antonio Barili (Siena, 1453 - c. 1529), dates from between 1483, the year the inlays were commissioned from the great carver by messer Alberto Aringhieri (the rector of the Opera del Duomo) for the chapel of St. John the Baptist, and 1504, the year in which the last payment is recorded. The undertaking took twenty years because, in the meantime, Barili was involved in other projects, but it was a complicated job nonetheless, since there were originally nineteen panels, all finely decorated and inserted into a structure that ran through most of the octagonal chapel of St. John the Baptist: the individual panels, each decorated with different figurations, were divided by small fluted pilasters surmounted by Corinthian capitals. Above the panels then ran an architrave, and above it rose a frieze, similarly decorated with animal and plant motifs, and the top was closed by a cornice. In the seven surviving panels we can still observe this structure, but we can only imagine how elaborate it was before the chancel was dismantled and dispersed. Even in ancient times, in fact, Barili’s work was in a poor state of preservation. This is how the erudite Alfonso Landi spoke of it in 1655 in his Racconto di pitture, di statue e d’altre opere eccellenti che si trovano nel tempio della Cattedrale di Siena: “tal opera fu agguattata, e tolta alla vista delle persone, et al loro godimento, perché fu messo in luogo quasi del tutto oscuro [...] rather that it has suffered from another bad encounter, because some paintings of it are stripped, and have suffered from woodworm, since perhaps it was placed so delicate work around walls that were newly built, and not yet sufficiently shaved.” Woodworm, neglect and moisture were thus the causes of the deterioration of Antonio Barili’s choir, which was dismantled as early as 1663.

Of eleven of the original nineteen panels we do not know the fate. One entered the collections of the Museum für angewandte Kunst (Museum of Applied Arts) in Vienna in 1869: it was the panel in which, a unique case for a carver, Antonio Barili portrayed himself in the act of carving wood, and it was destroyed during World War II (today it is known only through reproductions). The artist, in this panel, left his signature by affixing the inscription “Hoc ego Antonius Barilis opus coelo non penicillo exussi A.D. MDII” (“I, Antonio Barili, executed this work in the year 1502 not with the brush, but with the chisel”). The remaining seven are those from San Quirico d’Orcia: they were transferred here in 1749 thanks to the interest of Flavio Chigi, who took care to prevent the work from suffering worse damage than it had already had to suffer.

To get a closer look at the panels that we find today in the collegiate church, arranged behind the high altar, we can again avail ourselves of Alfonso Landi’s description, although they have been reassembled in an order that does not reflect the ancient one, for reconstructing which Landi’s work is nevertheless a valuable source. Starting from the left, in the first appears “a majestic door, from which a garden can be seen, and within it appear various shrubs with hanging fruits, and at the bottom there is a small table, in which there is an inkwell with pen, and a temparino, with a folder, which comes out of the said inkwell with these words: ’Alberto Aringheri Operaio fabre fatcum.’” The second is the one where “there is represented Saint Catherine of the wheels up to the hips, with the wheels underneath, disputing with the tyrant.” In the third we find “a man up to the hip, playing a lute,” and “above this man appears a garden with several shrubs.” The fourth is an unspecified saint “with face and right arms raised to heaven.” The fifth depicts “an organ corps with a man who with raised face is enjoying the sweetness of the sound, and in the side of the organ there is the coat of arms of the Opera, and below it is the coat of arms of Rector Aringhieri.” In the sixth here is “a figure of a young man with a folder underneath saying ’Joannis Baptiste discipulus,’” meaning “disciple of John the Baptist.” Finally, the seventh is the one Landi describes first: “an open cupboard, within which are seen and carved many tools of woodworkers and architects.”

|

| The panel with Antonio Barili’s self-portrait (formerly in Vienna, Museum für angewandte Kunst; destroyed during World War II) and the one with the tool closet |

|

| The panel with the saint and the one with the “majestic door” |

|

| The panel with the disciple of John the Baptist and the one with the man with the lute |

|

| The panel with St. Catherine of Alexandria and the one with the “body of organs” |

Barili’s chancel is an extraordinary work in several respects, beginning with the more distinctly documentary ones: two of the known panels give us a closer look at the carver’s craft, whose tools we see in the panel with the cabinet. Here then, on the upper level, are a bow saw, a small planer and a square, while on the lower level we find another planer, pliers, a ruler and a jar of glue. Of great interest then is the lost Vienna panel, where it was possible to see Antonio Barili at work with a shoulder knife: this was a tool that was maneuvered with the hands but rested on the shoulders so that the tool would provide better control and superior power. And stylistically, this is a work conducted with great skill. The search for the third dimension, with windows opening onto the characters, the exceptional chiaroscuro of the drapery (look at the sleeve of the saint with his right arm raised) obtained through juxtapositions of small portions of wood of different hues, the subtle carvings that recreate curls and locks of hair are all details that make Antonio Barili’s almost virtuosic skills evident.

Despite the fact that this work is little known to the general public, there have been many scholars who have dealt with the espaliers preserved in San Quirico d’Orcia: the artistic quality of the inlays, after all, is exceptional, and has been recognized since ancient times. Such a quality that has led to the suggestion of the hand of a great painter behind the cartoons: according to Carlo Sisi, it is possible that it was Luca Signorelli (Cortona, c. 1450 - 1523) who provided the design to Antonio Barili, given the obvious stylistic affinities of the choir once in Siena Cathedral with Signorelli’s production. Barili had given his inlays a pictorial connotation, seeking to evoke, through the use of wood, the effect of color-a characteristic that must have brought his work closer to that of a painter. Not only that: Sisi had found several similarities between the figures of the choir of San Quirico d’Orcia and those we find in the works of Luca Signorelli (in particular, the types that the artist from Cortona inserted in his paintings between 1497 and 1499, the period in which he was active in Siena, correspond to those that Barili used for the wooden stalls) and was convinced that the hand of a leading artist was behind the inlays. Before Sisi, others had tried to untangle this knot: Enzo Carli, for example, thought that the designer was Antonio Barili himself. However, the hypothesis seemed far-fetched to those who believed that a carver could not touch such high qualitative heights, also because we know of Barili’s other works that do not reach the level of the inlays in the Val d’Orcia today. Alessandro Angelini raised the hypothesis that the author of the cartoons might have been Pietro Orioli (Siena, 1458 Siena, 1496) by virtue of the sense for perspective that would unite the San Quirico d’Orca stalls with Orioli’s works. Indeed, many have wondered about the exceptional perspective views in the cycle (observe the figures of the saints, but also the incredible closet, endowed with astonishing illusionism): it is likely that Barili was aware of the solutions of Piero della Francesca (Borgo Sansepolcro, c. 1412 - 1492). More recently, Pier Paolo Donati has proposed the name of Bartolomeo della Gatta (Florence, 1448 - Arezzo, 1502), one of the leading Tuscan artists of his time, stylistically close to Luca Signorelli (although such a cue had already been suggested in the past).

But what did Federico Zeri, the scholar most closely associated with Barili’s work, think about it? The great Roman art historian found himself writing about the San Quirico d’Orcia inlays in a 1982 essay, in which he showed that he welcomed Carlo Sisi’s hypothesis, adding however: “whether or not the Signorellesque hypothesis is true, the fact remains that Antonio Barili’s inlays, in their transcending of the specific craft tradition, in their anti-classical allusions, in their relationship between space, figures and movement, do not constitute a text of local significance, but rather involve the entire Italian figurative situation between the end of the fifteenth and the beginning of the sixteenth centuries.” Antonio Barili’s inlays are, moreover, participants in that pierfrancescana culture that had taken to spreading from Urbino to the rest of Italy and that prompted many artists of the time to deepen their prospective researches: not even inlayers shirked this necessity, and Antonio Barili proves it with a choir that stands out for its search for perspective illusionism, the effect of which must have been particularly striking inside the chapel of San Giovanni. And that almost unreal linearity that distinguished the works produced in the context of Urbino culture is the same one that came to permeate the works of Giorgio De Chirico (Volos, 1888 - Rome, 1978), as Zeri himself suggested: “Strangely enough I found, in these inlays of the end of the fifteenth century, the same spirit that hovers in certain metaphysical paintings of De Chirico. This was precisely the encounter that changed my life.”

Reference bibliography

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.