St. Ignatius lived here. In the quiet of four rooms, four “little rooms” as everyone now calls them, in a little palace that he and his companions had built to give a first home to the Society of Jesus, after Pope Paul III, it was Sept. 27, 1540, approved the constitution of the order and granted the first Jesuits the chapel of Santa Maria della Strada, a little church that was a stone’s throw from Palazzo Venezia. Four rooms where St. Ignatius lived the last twelve years of his life. He had worked to succeed in implanting his base of operations in a convenient area to reach the heart, the brain, the bowels of the city. Near Palazzo Venezia, at that time an apostolic palace, therefore a papal residence. Close to the Capitol and the city government. Close to the palaces of the Roman nobility. Close to the neighborhoods of the city’s proletariat, the areas of taverns, stalls, and lupanariums. Close to the slums of the city, the areas of the last, the poor, the hungry, the sick, the outcasts, the wretched, the soldiers, the foreigners. From the windows of his small rooms, St. Ignatius saw Rome.

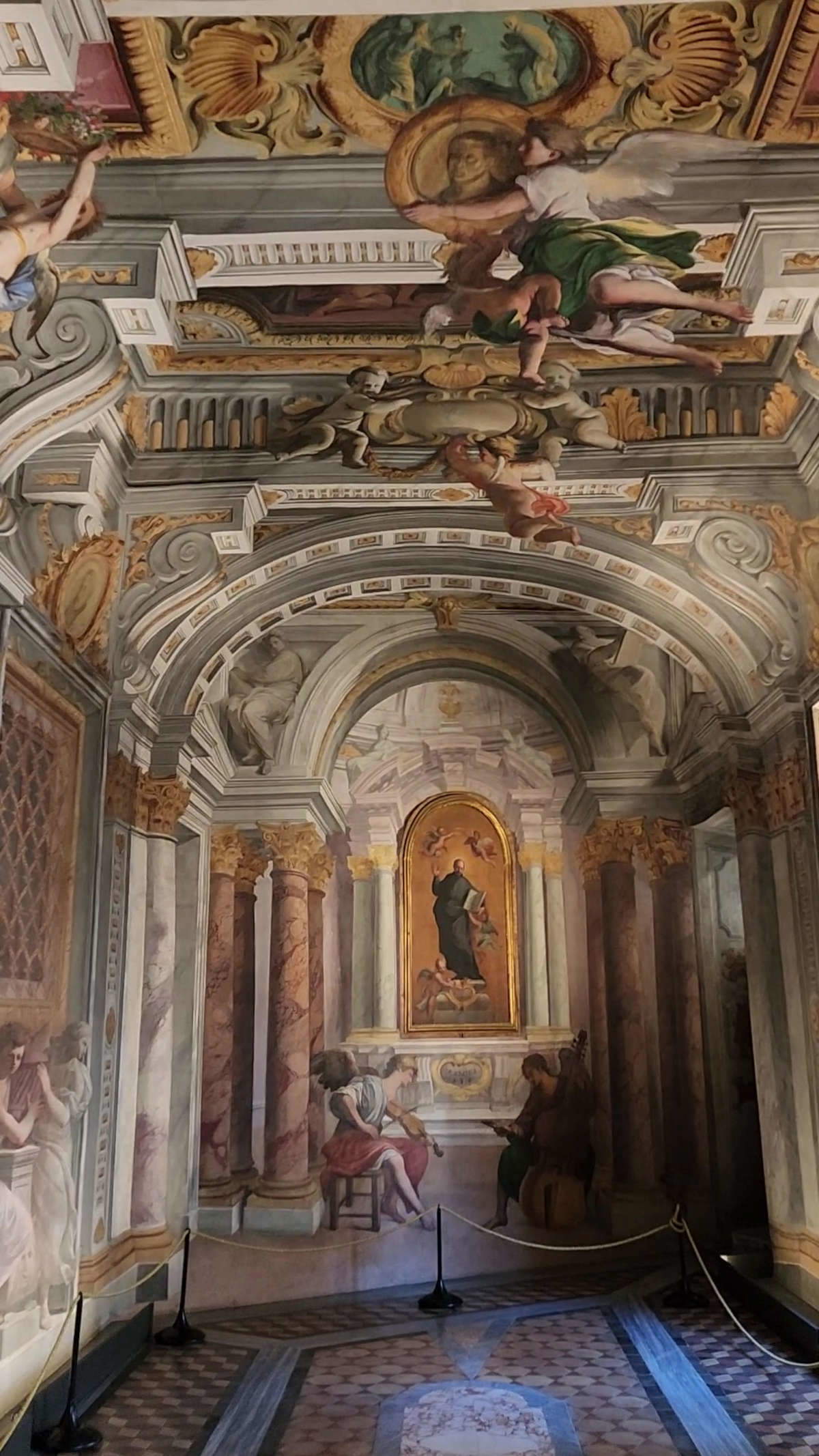

Those who claim that ancient art is easier to understand than the art of the present should jot down on their calendars a trip to Rome to see St. Ignatius’ little rooms. Of course: no one is stopping one from limiting one’s visit to a walk under the vaults of Andrea Pozzo’s corridor. There are plenty of guidebooks around and videos on social media encouraging tourists to look for the door to the Jesuit Casa Professa (it’s not even difficult: just walk out of the Church of Jesus, the mother church of the order, and take about ten steps to the left), cross its threshold, ask directions from the cleric ushering behind the desk at the entrance, marvel at the fact that the visit is totally free, climb the stairs to the second floor, find the Andrea Pozzo corridor, and sink for a few minutes inside the wonder. And, mind you, to experience something under the vaults painted by Pozzo would be a great achievement in itself: just outside these rooms, Rome is crossed every day by thousands of people who in front of the Pantheon, in front of Bernini’s monuments, in the presence of the ruins of the empire are not crossed by the most microscopic motion of astonishment. And we are not just talking about tourists; on the contrary: perhaps it is they, the ones most prone to wonder. In a barren expanse, one is content to find even a tiny fountain of water.

One senses, however, a jarring, a disagreement, almost a conflict between the splendor of Andrea Pozzo’s corridor and the secluded simplicity of the four modest rooms where St. Ignatius of Loyola spent the last portion of his existence, now refitted as a small museum that collects a good number of fetishes: a piece of his cassock, his shoes, chasuble, cloak. There is also an edition of the life of St. Ignatius written by Pedro de Ribadeneira, who was secretary to the founding father and who in 1586, exactly thirty years after the death of Ignatius of Loyola, had the biography printed in Venice that he had first drafted in Latin, then translated into Castilian and finally had it turned from Spanish to Italian by the publisher himself, Giovanni Giolito de’ Ferrari. There is this and little else: the small rooms where Saint Ignatius lived are cramped, bare, resigned, severe. White walls, terracotta floors, wood-beamed ceilings. You get there after passing through Andrea Pozzo’s corridor. And it seems to have been catapulted into another building, another time, another dimension. One seems to witness a quarrel, a discussion about two different ways of understanding faith. Was Andrea Pozzo, one wonders, then on the side of St. Ignatius of Loyola? Was the Jesuit Pozzo, by honoring the founder of the order with the account of his life, paying homage to the simplicity in which St. Ignatius had lived? Did those paintings go along with the thinking of that Basque soldier, that Iñigo who had served for eleven years in the Royal Army of Spain and then determined to devote his existence to the service of Christ after being shot in battle in Pamplona by a cannonball?

When St. Ignatius lived in these rooms, the corridor did not exist. It had been built, between 1600 and 1605, by the Jesuit Father General, Claudio Acquaviva, after the flood of the Tiber in 1598 had devastated the foundations of that house built on the cheap (“a shabby house that looked almost like a hut.” so had Prince Fabrizio Massimi marked it) when Paul III granted the Jesuits the chapel of Santa Maria della Strada, which stood where the Gesù Church stands today: it was demolished to make way for the order’s majestic new mother church. Next to Santa Maria della Strada, the Jesuits built the little building that was to serve as the order’s home. The first flood was enough to endanger it. To prevent it from being lost, Acquaviva ordered its radical renovation, we would say today, deciding, however, to save the four small rooms of St. Ignatius. A complex operation: it would have been simpler to tear down everything and redo the building from scratch. The project succeeded, however: a huge plaque on the facade still commemorates the laying of the first stone, which took place in the jubilee of the year 1600, under the auspices of the young Cardinal Odoardo Farnese, who financed the whole operation. A few years later, Girolamo Rainaldi, the architect in charge of the work, left the Jesuits a monumental building, which had been able to incorporate the small rooms of St. Ignatius by working on the supporting vaults on the lower floors and on the connecting rooms between the new rooms and what remained of the old palace. The corridor was one of these rooms: it was meant to be a simple passageway, and had not even been envisioned as an access to the little rooms.

Pozzo had found himself working on the paintings that Jacques Courtois, the Burgundian, had left unfinished when he died in 1676: he had been working on them for fifteen years. The need to decorate that corridor responded, meanwhile, to a practical need: the Casa Professa had long since become a place of pilgrimage. Devotees of St. Ignatius descended here from all parts of Europe, even before his canonization: already in the early seventeenth century the rooms had been transformed into four small, simple, unadorned chapels. Today, things have not changed: you happen to run into a few squads of the faithful who gather in front of the entrance to the Casa Professa and then, in the most dutiful silence, climb the grand staircase to experience the thrill of being for a few minutes in the rooms where, roughly five hundred years earlier, the saint prayed, meditated, wrote, ate, slept, and looked at Rome from his window. Courtois had begun working in the corridor before it even became the entrance to the small rooms: he had painted the spaces below the windows with episodes from the life of Ignatius of Loyola. In 1680, the superior general Giovanni Paolo Oliva wanted to renovate that corridor, became enthusiastic after seeing Andrea Pozzo’s work, and entrusted him with what would become his first Roman commission, viaticum to the later undertaking of the sumptuous vaulting of St. Ignatius Church. A painter of high caliber was needed, although the commission might have seemed modest: there was work to be finished that had already begun, and someone was needed who was capable of working in such a difficult, cramped, irregular environment. Oliva was to die shortly before Pozzo arrived in Rome, but the project was followed up with his successor, Charles de Noyelles, who took up the idea of dedicating a cycle of celebratory frescoes to the saint, and of making that gut “not [...] almost more a Corridor,” would have written the historiographer Lyon Pascoli, author of a series of Lives of Modern Artists, “but [...] a beautiful and most magnificent Portico of the same Chapels, which would make them, and more noble, and more venerable... [...] one of the most beautiful Sanctuaries in Rome, worthy to be admired, and revered, by any great Personage.”

“Ingredere aediculas olim incolae nunc patrono S. Ignatio sacras”: this was the inscription that Andrea Pozzo painted on the facade of access to the corridor, below the portrait of St. Ignatius, in the midst of the full figures of St. Luigi Gonzaga and St. Stanislaus Kostka, young Jesuit deities. “Enter the sacred chambers of Saint Ignatius, once resident, now patron.” And beyond the door an all earthly miracle takes place, the miracle of an artist who has bent the surfaces of the corridor to the illusions of his perspective games. No longer a corridor, but a spectacular gallery, like those that enriched the palaces of the nobles of the time. A gallery where there is no real architecture: there is only the painted one, which creates arches, beams, cornices, niches, openings in the ceiling. A gallery that moves along with the visitor, a gallery that follows him as he walks, that transforms under the effect of a powerful, surprising, mammoth anamorphosis that from the very beginning gives the feeling of being inside a much longer room than it actually is. On the walls, after the image of the Holy Family, episodes from the saint’s life flow: the miracle of the lamp oil in the cave of Manresa, the deliverance of the possessed, the angelic hand painting his effigy, the apparition to the prisoners, the healing of the infirm nun, the extinguishing of a house fire. Ribadeneira argues that Ignatius never performed miracles in his lifetime, but it does not matter: mystical fervor mattered more than exact adherence to historical facts. For the mentality of the devotees of the time, it was the prodigious, rather than the rational, that proved the accuracy of a fact, the exceptionality of a person. And then, in the center of the vault, Saint Ignatius is carried in glory by angels. In the center of the floor, on the other hand, a marble rose suggests the exact point at which to position oneself in order to appreciate the maximum degree of credibility of the illusion: at that point, the faux architecture imagined by Andrea Pozzo appears straight. Then, if one moves, one realizes that the vault is curved, going backwards the beams rise upward and become arches, and if one proceeds to the end of the corridor the cornices slope downward, the figures tend to deform, one no longer sees graceful putti holding flowers, but obese and disfigured little angels. This was the first time Pozzo had tried something like this: it cannot be ruled out that he had kept in mind a work by Athanasius Kircher, published a few years earlier, theArs magna lucis et umbrae, a treatise on the study of light in which space was also given to perspective and how to straighten spaces by the sole use of perspective modifications was discussed.

On whose side was Andrea Pozzo then, on whose side were the superior generals who put him to work? How could the splendor of his paintings be reconciled with the works of a saint who had dedicated his life to the last, the orphans, the sick? And why honor him with a perspective machine that seems almost devilish, with figures that become unwatchable monsters if the visitor strays too far from the marble rose? The theological reasons for the apparent jarring between the poverty of the chambers and the richness of the apparatuses must be sought in the work of Ignatius of Loyola himself, who had considered contemplation, for him a form of prayer, also as a dimension that is exercised by seeing. Contemplation involves the faithful with all the senses. The vision of a place, of a story, is a very, and inescapable, part of one’s relationship with divinity. For St. Ignatius, one participates in the divine by means of sensory experience: in his Spiritual Exercises, the saint prescribes “to see with the imagination the material place where what I want to contemplate is,” such as “the temple or a mountain where Jesus Christ is.” Art is then a form of mediation: the object that the artist represents is not physically present, but lives in the imagination of the devotee, and the devotee exercises his imagination by means of art. Roland Barthes believed that the Ignatian image was not a vision, but a view in the strict sense of the term, a view to be considered “in a narrative sequence,” and the involvement of the senses should help the devotee construct an image to which he or she can continually return with his or her mind. St. Ignatius called this image “composition.” “To see with the imagination,” he wrote again in the Spiritual Exercises with a contemplation on the Nativity in mind, “the road from Nazareth to Bethlehem, considering how long and wide it is, and whether it runs in plains or through valleys or over heights; likewise to see the cave of the nativity, observing whether it is large or small, low or high, and what it contains.” See people, what they say, what they do. Picture with one’s imagination the scene of the nativity. And then praying.

Art is a form of composition, the work of art is the means that allows the devotee to enter more easily into a narrative, to observe the protagonists of the scene as St.Ignatius, “contemplating them and serving them in their needs, as if I were there present, with all possible respect and reverence,” and then “reflecting on myself to derive some fruit.” The work of art is the tool to be even more present in contemplation, it forces the mind to focus, it offers the devotee the elements to access the narrative of the mystery, it encourages the involvement of the senses.

For the Jesuits, the work of art was a theater of religious performance. And for Andrea Pozzo, this sacred theater takes on the guise of a perspective play: perspective, he would later write, in 1693, in Perspectiva pictorum et architectorum, is “a mere fiction of the true,” which does not oblige “the painter to make it seem true from all parts, but from a determinate one.” Outside that determinate part there is only deception. Pozzo, a Jesuit himself, perhaps had kept well in mind the Ignatian teaching on discernment. That is, the ability, the Jesuit Bergoglio would have said, to recognize the signs by which God manifests Himself in life’s situations. It was an indispensable element of every Jesuit’s formation: Pozzo’s unique point of view, noted scholar Lydia Salviucci Insolera, could then be considered a metaphor for the discernment that helps Christians distinguish the true from the false, the eternal from the ephemeral, the real from the illusion. Andrea Pozzo, with his perspective plays, was responding to a theological need. The marble rose opens to the vision of God, places the Christian in a position to grasp the truth, keeps out deception, the false, and evil. The corridor thus becomes a metaphor for the Christian’s journey as he proceeds between appearances and finally comes to the vision of truth. Outside the vision of God, there are only illusions. Those illusions that, once the trick is figured out, attract so much of our attention. Those illusions that move our wonder today. Andrea Pozzo may not have taken into account how fascinating they are, the illusions.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.