The figure of Felice Casorati stands out on the early twentieth-century Italian art scene as a silent, rather secluded, but deeply incisive presence. His art, a refined, cultured art, traversed the major currents of the century with independent step, yet always abreast of the achievements of the avant-garde. His art, now documented in a major exhibition at Milan’s Palazzo Reale (curated by Giorgina Bertolino, Fernando Mazzocca and Francesco Poli, Feb. 15 to June 29, 2025), thus went through various phases. He was at first Symbolist, for some time he even opened up to the Viennese Secession and painted works close to those of Klimt, then there was a period of juxtaposition with Cézanne, and then, in the 1920s and 1930s, Casorati’s poetics can be included in the various trends of the return to order that characterized that historical period. However, among the lines that run through his production, there are several constant threads: one of these could be identified in a precise feeling, melancholy. A feeling that is not only a psychological figure, but also becomes a kind of structuring principle of a vision, a relevant component of his painting. A theme, this one, that runs through Casorati’s works from his Paduan beginnings to his maturity, and is revealed in his choice of subjects, composition, colors, posture of the figures and even in the mental arrangement of spaces.

The early years of the century saw Casorati make his debut in a still strongly Art Nouveau and Symbolist context. But it is the Neapolitan period, between 1907 and 1911, that represents the first nucleus of a melancholic poetics in Casorati’s work. In letters sent to his friend Tersilla Guadagnini, the young Felice describes himself in a restless, almost distressed state: “How strange I am! [...] it seems to me that I have lived not a true, complete, common life, but a semi-life, a life of sleep,” and again, “I have always been a great dreamer, and perhaps I still am,” or “I persuaded myself of the futility of every effort, of every attempt [...] it was not only humiliation mine... it was also pain - intense pain - complex - intrusive.” Words that speak not only of private suffering, but of a dark and exhausted inner dimension, in which the futility of every effort becomes the only truth. It was in this climate of gloomy isolation that Casorati took refuge in the silences of Capodimonte, contemplating ancient art and creating The Old Women, a painting that he himself considered the synthesis of those early solitary studies. A canvas imbued with a heavy and immobile atmosphere, which seems to quote Bruegel’s Parable of the Blind, but in which melancholy is not only the subject, but the very substance of the painting.

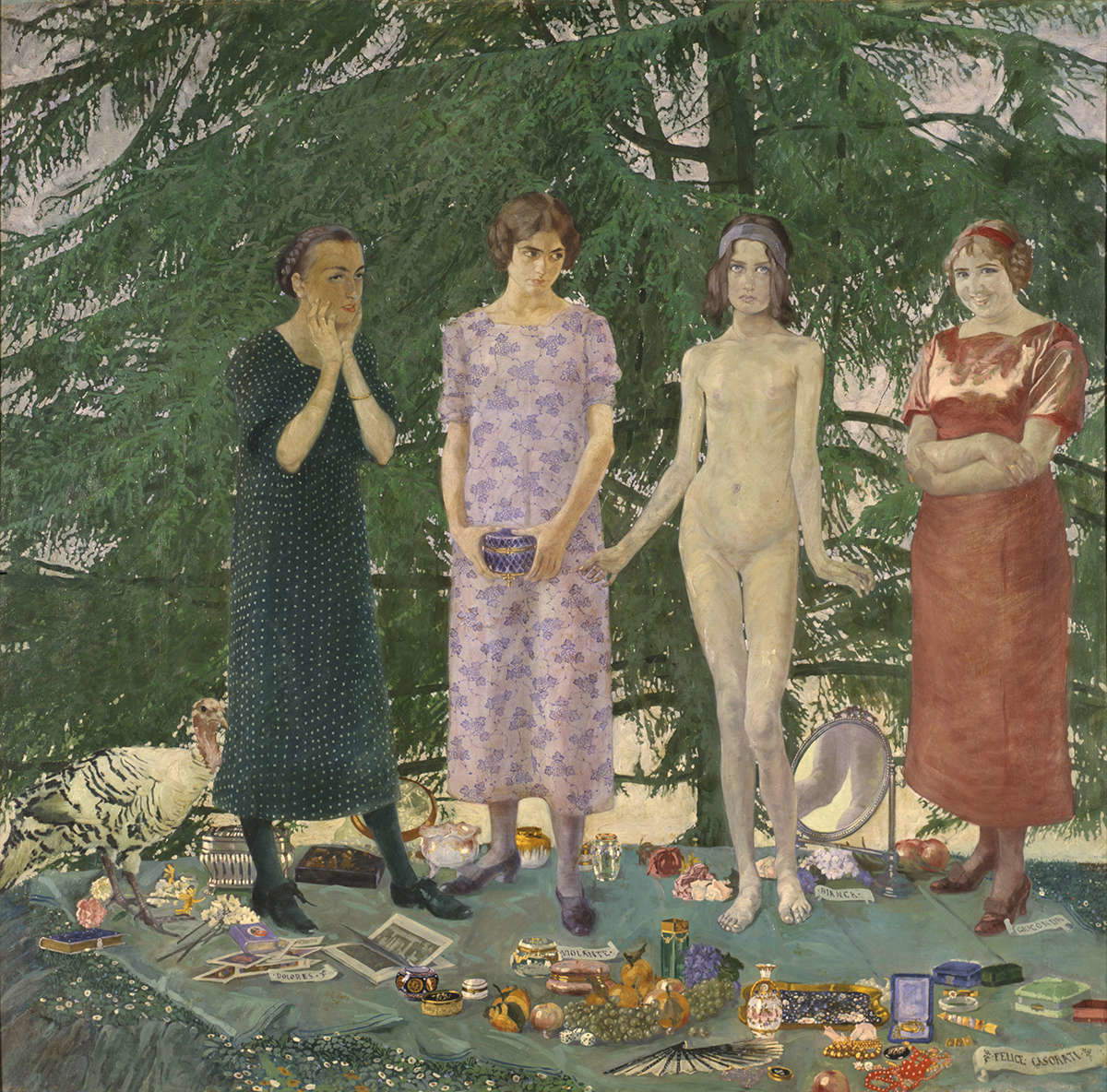

Marking a formal and thematic turning point is the large painting The Young Ladies of 1913. Monumental, enigmatic, with a Symbolist imprint, the work is offered as a gallery of moods embodied by four female figures, namely Dolores, Violante, Bianca and Mona Lisa. “Differently posed and dressed, they are identifiable-partly thanks to the cartouches that appear at their feet-starting from the left in Dolores, personification of mourning, Violante of melancholy and existential restlessness to which the purple of her dress and her recumbent head refer, Bianca, innocent in the purity of her adolescent nude reflected in the mirror,” writes scholar Fernando Mazzocca. “She is the one who most attracts attention in the painting overloaded with details and precedes Mona Lisa, whose name, flamboyant dress and wedding ring on her finger make her the emblem of a fulfilled life. Its purchase by the International Gallery of Modern Art at Ca’ Pesaro represented Casorati’s decisive consecration.” Violante, then, is the personification of melancholy: an icon of the painter’s restlessness, set in a rarefied landscape reminiscent of Botticelli’s “Primavera,” but emptied of all joy. This painting represents a true ritual passage for Casorati: the landing to a painting that no longer describes, but alludes and symbolizes. Melancholy here becomes a pictorial concept, an entire emotional structure translated into color, gesture and posture.

The years immediately following confirm the artist’s trajectory toward an increasingly interior vision. Painting becomes "unreality,“ as he himself writes (”they are not paintings: they are unrealities painted without skill"), a projection of the dream. In paintings like La Via Lattea or Notturno, Casorati tries to paint the images he sees in dreams, populated by “invisible beings,” “hallucinations,” “pure spirits.” This is a period in which melancholy is sublimated into lyrical abstraction, amid the influences of Klimt and Kandinsky, in a language that rejects reality in order to inhabit its transparency. Even in his graphic and sculptural production, melancholy is expressed in essential, almost archaic forms, as in the 1914 Mask, which seems to evoke a humanity suspended between the ancient and the otherworldly, awe and silence.

Further developments knew Casorati’s art in the 1920s. At the 1928 Venice Biennale, which comes four years after the pivotal juncture of the 1924 Biennale (where the artist presented as many as fourteen works in a solo exhibition that was highly praised by critics: the success was mainly due to the fact that here the Piedmontese artist embraced the new classicist tendencies with skill and with numerous and uncovered references to ancient art), Casorati presented Scolari, a work that marked another change in his poetics. The girls sitting in the classroom are motionless, silent, almost embalmed in time. The objects seem suspended, the scene locked in a waiting condition that amplifies the sense of estrangement. Melancholy here becomes a lyrical suspension of reality, a form of domestic abstraction, an atmosphere that characterizes many works of this period. The painting, even in its apparent realism, moves in the register ofenigma: the restrained gestures, the vague glances, the unstable balance of space speak a silent language of shyness and loneliness.

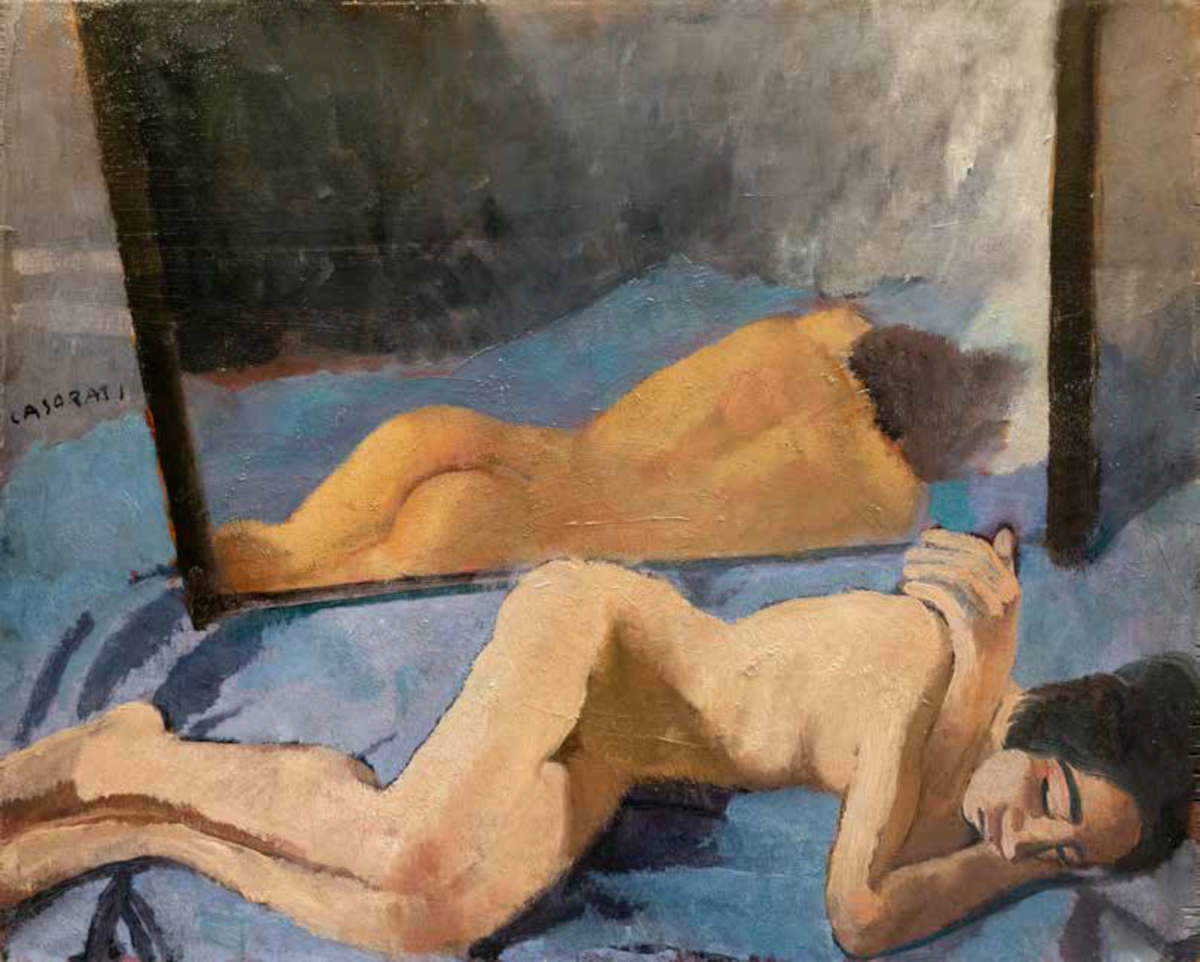

In the 1930s, the female figure became increasingly prominent in Casorati’s painting, embodying a psychological but also archetypal melancholy. “The melancholic, silently meditative attitude, also veiled by an intimist dimension of bewilderment and expectation,” writes scholar Francesco Poli, “is one of the aspects that specifically characterize many of the women and young adolescents, nude or clothed, that Casorati depicts in the 1930s (and even later) with a particular pictorial tension suspended between psychological sensitivity and compositional detachment.” In Woman with Mantle (1935), for example, the protagonist is huddled on a chair, wrapped in a green blanket: only her bare shoulder and a stooped, absorbed, abandoned face emerge. The body, more hidden than revealed, tells of restrained emotion. Similar is the feeling in Ragazza a Pavarolo, where the young woman sits in a bare studio, hands in her lap, head down: a silence that weighs like an identity. But it is with Sleeping Girl (1931) that melancholy reaches an almost uncanny dimension. The naked, bony body is reflected in a mirror: a double that could be another being. The scene is domestic, but uninhabited, like an empty dream.

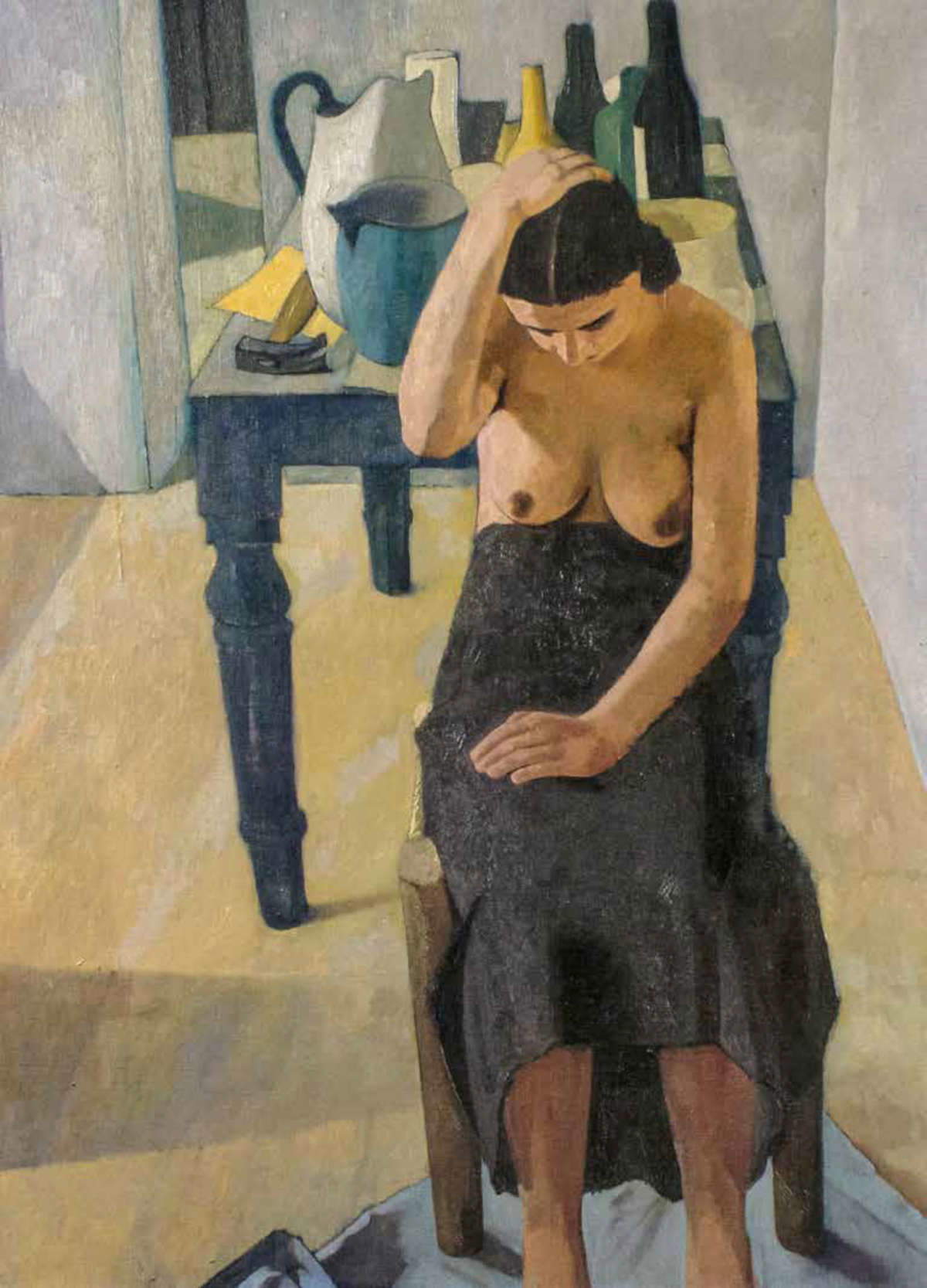

Then in 1936, Casorati painted Woman Before the Table, among his most intense works. The nude body, bent over, hands in her lap and on her head, is surrounded by gracefully arranged objects: jugs, bottles, and even a hammer - ironic but disturbing. The figure’s gesture is dramatically restrained, symbolic of an emotion that never explodes but remains imprisoned. It is the melancholy of presence, the one that does not scream but resists: a still, almost metaphysical pain.

Melancholy, for Casorati, is not just feeling. It is a compositional principle, a way of ordering the world through art. It is the empty space between objects, the shadow surrounding the face, the always restrained posture of bodies. It is the will to subtract the noise, the narrative, the excessive gesture. An art that seeks the absolute through the unfinished, that inhabits the dream with the awareness of its fading. At the time of the avant-garde, at the time of the breaking of patterns, Casorati, while looking at new poetics and while always remaining among the most up-to-date artists of his time, never stopped trying to give voice to melancholy.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.