"Intra Tupino and the water that descends / of the hill elected by blessed Ubaldo, / fertile costa d’alto monte hangs. " In this triplet of Canto XI of Paradise, in which there is a eulogy of St. Francis delivered by the Dominican St. Thomas Aquinas, Dante uses a geographical periphrasis to point to Assisi, the birthplace of the saint of humility and poverty. In the opening of the triplet, the supreme poet uses two rivers as the boundaries of the indicated territory. The first is mentioned by its proper name, while the second is described with a further periphrasis that, when analyzed, leads to the identification of the Chiascio River, which flows from the slopes of Mount Ingino, one of the five hills symbolic of Gubbio. The name of the mountain is also not mentioned explicitly, but Dante chooses a figure with strong evocative power to identify it: it is St. Ubaldo, bishop and patron of Gubbio, who died on May 16, 1160, and whose basilica, which preserves his remains, is located at the top of the aforementioned mountain in Gubbio. It is in his honor that every May 15 the Festa dei Ceri is held, during which the ceri, large, vertically developed wooden artifacts, are carried around the city and at the end of the day are brought back, in a spectacular run, to the basilica. The fact that Dante used this character to arrive at his identification of Gubbio is indicative of the deep connection that existed between the saint and the Umbrian town, known even outside the narrow territorial context.

Ubaldo Baldassini was canonized by Pope Celestine III in 1192, but popular devotion already invoked him as a blessed and saint. One of the central elements of the veneration of St. Ubaldo is the incorruptibility of his body, an element that was considered an obvious sign of sanctity. In the two ancient biographies of the saint, the Vita Beati Ubaldi by Giordano, canon and prior of San Florido in Città di Castello, and the Vita Beati Ubaldi by Tebaldo, Ubaldo’s successor in the Episcopal chair in Gubbio, there are no references to treatments of the deceased body. The first burial took place in the Cathedral of Saints Marian and James near the high altar, inside a marble ark. According to tradition, but without documentary evidence, he was transferred on September 11, 1194 to Mount Ingino.

It was in the first half of the fourteenth century, perhaps between the third and fourth decades, that the need to find a new location for the saint emerged. This was the period in which Gubbio saw the pinnacles of its communal experience, with the planning and realization of an important public space such as Piazza Grande and the public palaces overlooking it, that of the People (today Palazzo dei Consoli) and of the Podestà, as well as the elaboration of communal statutes. In this municipal fervor, it was thought that for the precious remains of one’s patron saint it was necessary to find a solution that would allow its preservation, but also the display of the precious relic, which in this case was represented by an intact body. There is no documentary evidence regarding direct municipal involvement in the commissioning of this new reliquary, but it should be remembered that the cult of St. Ubaldo was not only a religious, but also a civic matter: in fact, the promotion of his cult was included in the municipal statute of 1338.

|

| View of Gubbio |

|

| Palace of the Consuls |

|

| The basilica of Saint Ubaldo. Ph. Credit |

The choice fell on the realization of a monumental wooden case with gabled slopes, inspired in form by the goldsmith’s reliquary-cases widespread throughout Europe. It was designed to be viewed 360 degrees, and in fact decorations appear on all sides. The types of wood used predominantly are walnut and elm. The latter, besides being available in abundance in the area, recalls a legend about the translation of the saint’s body. St. Ubaldo asked his successor to call a three-day city fast: at the end of this, he was to place his body on a wagon drawn by untamed, unguided heifers, and the place where they would stop, that would be the place chosen. So it was done, and the animals stopped at the top of Mount Ingino, near a small church dedicated to St. Gervasius. The branches used to lash the heifers were planted in the ground and became two elms. In this way, a new town worship center was created, with the ambition of making it a new pilgrimage destination.

The main goal of this renovation was to find a solution that would allow the remains of St. Ubaldo to be visible on selected occasions, without compromising its preservation. It was therefore planned to create an upward-opening flap on the front elevation, which was secured by two iron rods. On the inner surface of the flap was painted a starry sky, of which only slight traces remain today. Once opened, one faced an iron grating. Beyond, as two iron eyelets inside the case probably denote, there was an additional fabric curtain that was moved through a mechanism to reveal the body of the saint. The effect achieved was similar to what can be seen in some marble funerary monuments, where it is two angels who move the fabric curtain to reveal the body of the deceased (one can take Arnolfo di Cambio’s celebrated Funeral Monument of Cardinal De Braye as an example). In the 1600s, glass was also inserted beyond the metal grating. As noted earlier, the forms of thisark, known today as theold ark of St. Ubaldo, are inspired by the reliquary-cases made by goldsmiths, but also recall the models of ancient marble sarcophagi, particularly in the external decorations. Indeed, the flap features lacunars that were to be decorated with an inlaid eight-petaled rosette, which were lost during a later restoration. The other elevation also features lacunars decorated with phytomorphic and geometric motifs. Another detail are the wooden inlays inspired by cosmatesque motifs, which embellish the artifact. On the elevations of the short sides, on the other hand, there are four lacunars arranged in two registers.

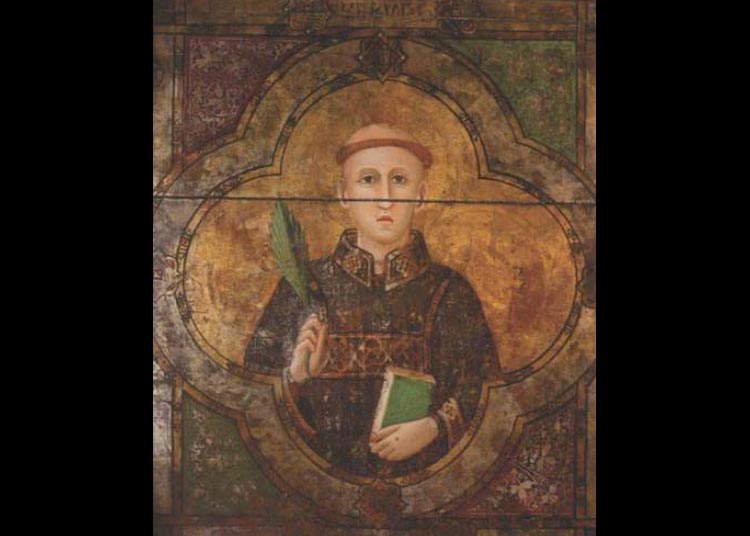

In addition to the gilding, there were a number of paintings on the inner surfaces of the ark , a total of seven. Unfortunately, only the two placed on the short sides have been preserved: they depict, each within a poly-lobed frame, Christ Blessing and a Deacon Saint (perhaps St. Marianus or St. James, i.e., the titular saints of the Eugubinian Cathedral). These figurations were hardly visible from the outside, even at the time when the flap was open. In fact, their presence was functional not so much for the faithful, who could only catch a glimpse of them, but rather for the saint: they assumed a liturgical function, protecting and accompanying the body of the deceased bishop. Their position inside the casket allowed them to be excellently preserved. The figure of Christ stood at the head of St. Ubaldo: in his gesture of blessing one can detect an attempt at foreshortening, at the creation of spatial illusionism, manifesting a willingness to carry his hand beyond the pictorial space. This figure stands in fruitful comparison with the Blessing Christ of the under arch of the entrance to the right transept cloister in the Lower Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi. We are dealing with a painter who knows the site of the Lower Basilica well: not only Giotto, but also Simone Martini. In fact, with close observation one notices the attention to the depiction of certain details, such as the saint’s eyelashes, typical of the Sienese painter’s approach. Regarding the quadrilobes of the back wall, now lost, there is a description from 1924 in which four angelic figures are reported: a likely hypothesis, considering that in many coeval marble tombs they were present. In the spaces between these were inserted some colored glass, with a conception quite similar to that of verre eglomisè, to make the surface more precious, recalling outcomes of goldsmithing.

|

| Master Expressionist of Santa Chiara (Palmerino di Guido), Old Ark of SantUbaldo (third decade of the 14th century; painted wood; Gubbio, Ubaldian Memories Collection). Ph. Credit Festival of the Middle Ages |

|

| Master Expressionist of Santa Chiara (Palmerino di Guido), Old Ark of SantUbaldo (third decade of the 14th century; painted wood; Gubbio, Ubaldian Memoirs Collection) |

|

| Master Expressionist of Santa Chiara (Palmerino di Guido), Old Ark of SantUbaldo, detail of the blessing Christ |

|

| Master Expressionist of St. Clare (Palmerino di Guido), Old Ark of SantUbaldo, detail of the deacon saint |

It was Pietro Toesca who recognized the importance of these paintings and attributed their hand to the painter whom Henry Thode, at the beginning of the last century, called the Master of St. Clare, or that artistic personality who was responsible for the decoration of the main vault of the church of St. Clare in Assisi. Roberto Longhi called him a “bittersweet expressionist,” and Giovanni Previtali, on this consideration, added the attribute “expressionist” to the previous designation. Enrica Neri Lusanna advanced the attributive proposal of recognizing in the Master Expressionist of Santa Chiara the painter Palmerino di Guido (news from 1299 to 1337), father of Guido Palmerucci. The activity of this painter in Gubbio, between the 1920s and 1930s, is found in the church of Santa Maria dei Laici, the church of San Francesco and the church of San Secondo. Perhaps he also worked for the church of Sant’Agostino, for the canons of the Cathedral and for the Municipality.

The presence of paintings inside the ark correlates with some reliquary-boxes from the Umbrian area, such as those of St. Clare of Montefalco and St. Rita of Cascia. In these cases, however, the opening was more traditional, that is, it was done from above.

The ark was most likely placed on small columns behind the high altar. Two majolica tiles from 1521, glazed by master Giorgio Andreoli (preserved at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the Metropolitan Museum in New York), show the tomb of St. Ubaldo placed on pillars. In reality, not the ark is depicted, but the body itself, probably with the intention of making visible what was in reality concealed, the uncorrupted body. These images help to give us an idea of how St. Ubaldo’s tomb must have been set up.

In 1471 the ark underwent an initial restoration. The next intervention, which took place between the second and third decade of the sixteenth century, was promoted by the Congregation of the Lateran Canons Regular, who took up residence in the basilica in 1512. The case was updated according to the new Renaissance taste, such as the additions in gilded tablets, undergoing a profound rearrangement from how it was originally conceived. In the side cusps, the trigram of St. Bernardine of Siena, a figure to whom the Lateran canons were linked, was inserted. At the structural level, however, it did not undergo any changes.

|

| The new urn of St. Ubaldo. Ph. Credit |

|

| The convent of St. Ubaldo, home of the Collection of Ubaldian Memories. Ph. Credit |

This ark held the remains of St. Ubaldo until August 30, 1721, when he was moved to a new tomb (hence the adjective “old”). From that time, this artifact became a Ubaldian memorial. Immediately the Lateran Canons Regular claimed rights to possession of the old ark. It is reported in the basilica still in October 1876, while in 1884 it was transferred to the Palazzo dei Consoli. A very significant episode should be highlighted. The municipality received a proposal to purchase the ark from a local antiquarian. The proposal was firmly rejected: with great civic self-consciousness and a certain idea of protection of its artistic heritage, the city council declared “not to be a decent thing for the City Hall to dispose of an ancient object, maximum at a time when for the sales made of private individuals complained that our city was losing all ancient memories” and that “not only because of its antiquity but also because of its religious traditions it constitutes an object for many that is valuable and respected” (the testimony is reported in Francesco Mariucci, L’arca vecchia di Sant’Ubaldo. Memoria e rappresentazione di un corpo santo, Edizioni Fotolibri Gubbio, Gubbio 2014: the volume, accompanied by an essay by Andrea di Marchi, is the point of reference for the knowledge of this particular artifact, and edited by the same author is the file on the old ark present in the catalog of the exhibition Gubbio al tempo d Giotto. Art Treasures in the Land of Oderisi held in the Umbrian town in 2018).

Its subsequent moves, always within the city, are noted in 1888, to Palazzo Pretorio at the Pinacoteca, then following it in its relocation in the early twentieth century to Palazzo dei Consoli. Later the City Council organized a collection of sacred relics in the Church of Santa Maria Nuova, where the old ark also converged. It was restored again in 1982 and in 1997 brought back to the Basilica of St. Ubaldo. Today it is kept at the Collection of Ubaldian Memories, which can be accessed from the basilica’s cloister.

In addition to having an intrinsic artistic value, theold ark of St. Ubaldo is a valuable testimony to how a specific need regarding the worship of one’s patron saint caused a new artifact to be developed that could fully meet that need. A clear example of how artistic testimonies guard the stories of our communities.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.