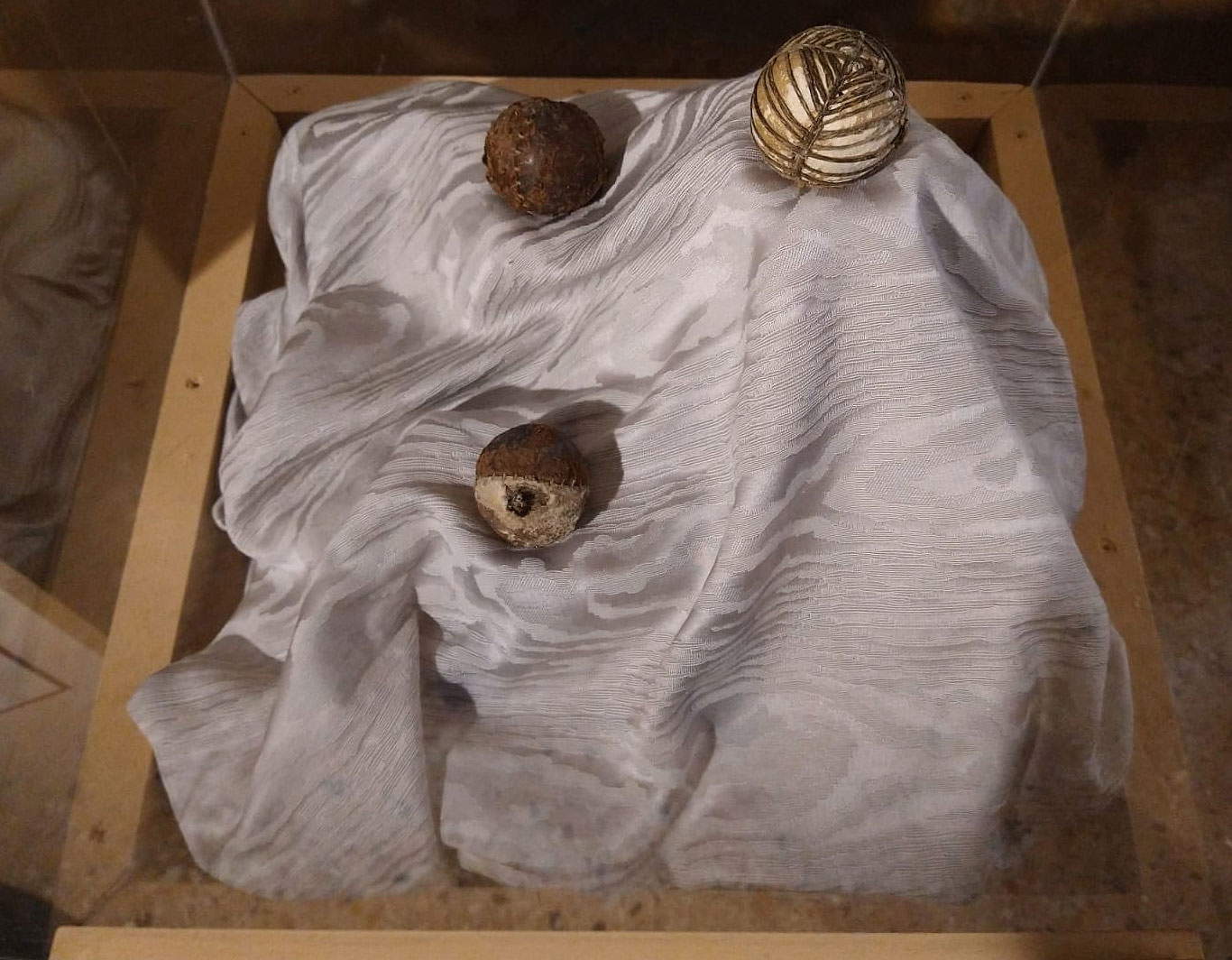

If one wanders around the rooms of Palazzo Te in Mantua, in one of the rooms immediately after the Camera dei Giganti one cannot help but notice a case that holds three game balls: these are the three “ballette” found right in Palazzo Te, and which in the 16th century were used for a game very similar to modern tennis. A sport that has ancient origins: interestingly, the first reference to tennis appears in the work of the Florentine chronicler Donato Velluti, who between 1367 and 1370 drafted a Cronica domestica. In the treatise, Velluti recounts the events leading up to the Battle of Altopascio, fought by the Guelph forces of Florence, Siena and the Papal States against the Ghibelline coalition formed by Lucca and Milan and led by Castruccio Castracani. In 1325, before the battle, five hundred French knights, allied with the Florentines, arrived in Florence, and it seems that a personage of the time, a certain Tommaso di Lippaccio, spent his days playing “tuttodì a la palla colloro, and at that time it was begun here to play tenes.” Velluti’s Cronica is the only known text in Italian from the medieval period in which the word “tennis” is expressly used, which would therefore seem to be of French derivation. However, attestations are rare: in fact, we have to wait until 1401 to find another occurrence of the term, in an ordinance of the city of Utrecht in which people are forbidden to “teneyzen” (i.e., “play tennis”) on the courts in the Oudwijk district.

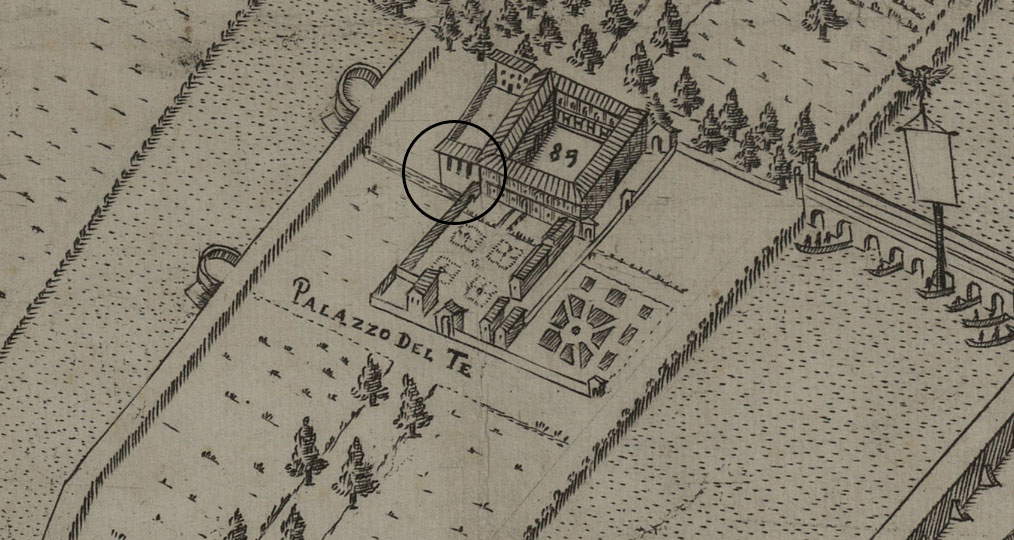

We do not know exactly where the word “tennis” comes from, and various hypotheses have been made. The most reliable is probably the one that, as anticipated, links the term to the French language: the English lexicographer John Minshew (1560 - 1627), in his treatise Ductor in linguas, noted that “tennis” (in the text the word is spelled just as we write it today) “is the word that the French [...] usually pronounce when they hit the ball.” It would therefore be a derivation from the verb “tenez,” “take,” with which the French would have accompanied the strokes. The explanation is not entirely convincing, Heiner Gillmeister explains in his Tennis: a cultural history. Meanwhile, it is not clear why the word “tennis” was used to describe this game in Italy, England and the Netherlands, but not in France, where the expression jeu de la paume (“palm game,” due to the fact that originally the ball was hit with the hands, first bare, and then covered by special gloves) was preferred. Moreover, no other historical attestation of the custom mentioned by Minshew is known. It remains a fact, however, that in the sixteenth century tennis must have been widespread: returning to Palazzo Te, historian Ugo Bazzotti explained that in 1502, before the construction of Frederick II’s pleasure residence, a building had been erected near the horse stables of Francis II (who had the area reclaimed and then had stables installed there) specifically for the game “of the Racquet,” which was very popular with the Gonzaga court (so much so that other similar structures would be set up near Palazzo San Sebastiano and the Ducal Palace). The building was later demolished in 1784 but is noted in the Urbis Mantuae Descriptio, the map drawn in 1628 by Gabriele Bertazzolo.

Emperor Charles V also played tennis in Mantua, as recounted by the man of letters Luigi Gonzaga I di Palazzolo in his Chronicle of Charles V’s sojourn in Italy (which Luigi Gonzaga witnessed directly), between July 1529 and April 1530: the text contains an account of a game of doubles that pitted Charles V and monsignor di Balasone against each other, and Ferrante Sanseverino, prince of Bisignano, and monsignor de la Cueva against each other: “giocorno a detta palla forsi quattr’hore, dove sua Maestà si exercitava molto bene et assai ne sa di tal gioco, et giocavano di vinti scudi d’oro la partita, dove alla fine sua Maestà prendere sexanta scudi. Et poi fornito, sua Maestà se ne ne ritornò in camara solamente con li soi Camarieri, et si mudò di camisia, et alquanto se rinfrescò, et stette così per un pezzo ad riposare.”

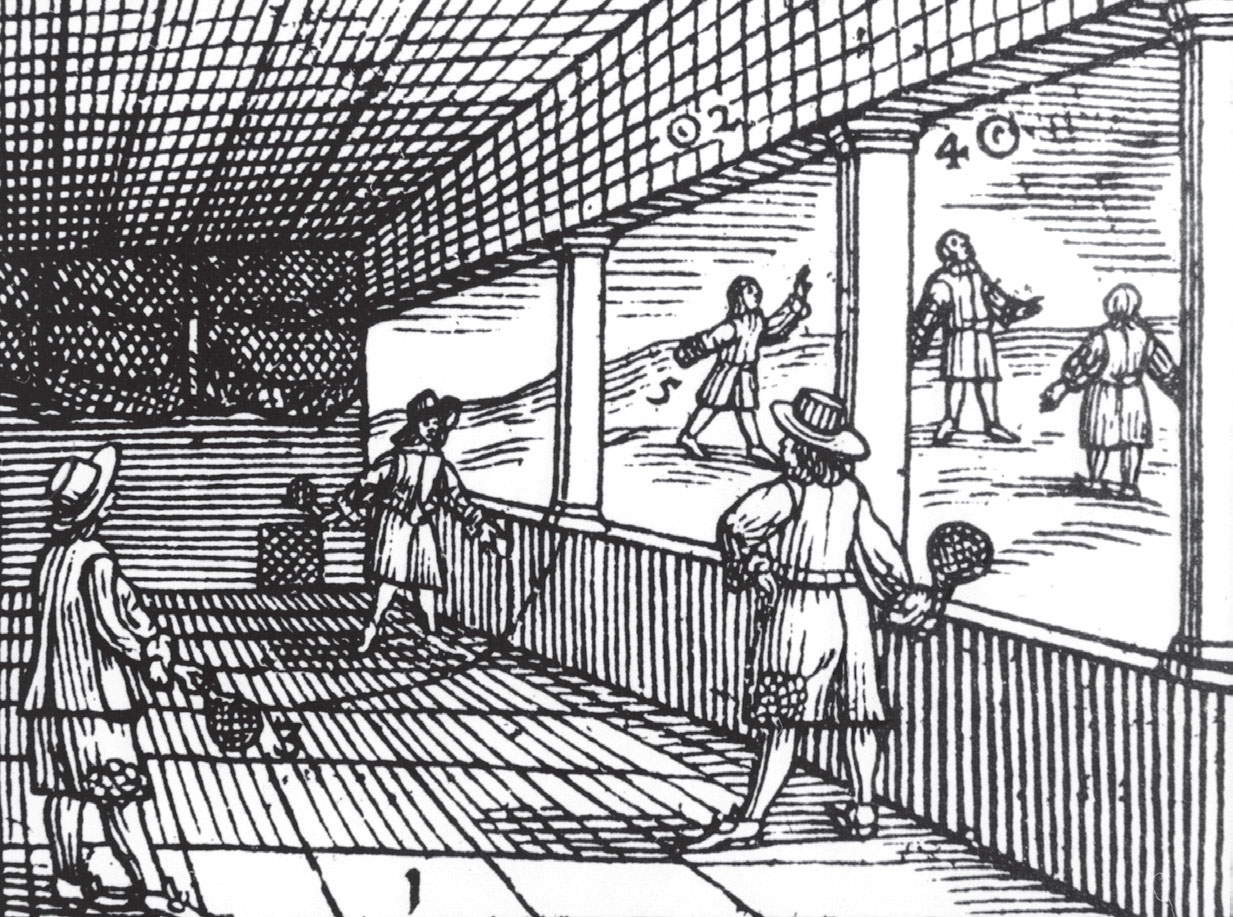

How was tennis played back then? We can get an idea of it by reading Antonio Scaino da Salò’s Trattato del giuoco della palla, a work from 1555 in which the “giuoco della palla” is defined as “such a noble and rare exercise, so beneficial to the body and soul, helping principally to the purification of the spirits, with which our soul does all its operations, insino that of understanding.” One could play one against one, two against two, or even “three on each side, et with more numbers, as best suits them, et according to the capacity of the places.” The “beaters” serve the ball by “driving it toward the opponents, called in that case the rebaters, who at the meeting try to rebound it toward those others, and in this way the contrast lasts until the ball ceases to move, either by itself lacking the violent vigor in it concocted by the beaters, or by the rebaters,” or because it has stopped on the ground. At the point where the ball ends its path, a point is scored, the “hunt,” which is valid if the ball has not left the field of play or if a player has not committed a foul (i.e., an infraction of the rules of the game, which occurs when one holds the ball with the hand or with other parts of the body, or even when one hits the ball with two touches). In order for a “hunt” to be scored, the ball, as in contemporary tennis, must be hit in the air or after the first bounce: you cannot hit the ball after the second bounce, or if it rolls on the ground. The game “does not come to an end for gain made from a single hunt, but more hunts are to be acquired by those who intend to bring back an accomplished victory.” The game is won by the one who scores four points in a row, or if he gets to five in case the opponent wins one hunt, or to six if the opponent scores at least two, and finally to eight if the opponent scores at least three points, but with the rule that the winner must still have at least a two-point gap over the rival. The rules also included service changes and court changes, as in today’s tennis. The court had at its center the ancestor of today’s net, a rope that was stretched out in the middle of the court (hence the name by which tennis became known in Italy, “pallacorda”): we know of this rule from the treatise of a Spanish scholar, Juan Luis Vives, who in a passage of his 1539 Exercitatio linguae latinae, where the rules of tennis are explained, reads “sub funem misisse globulum, vitium est” (“if the ball ends up under the rope, it is foul”).

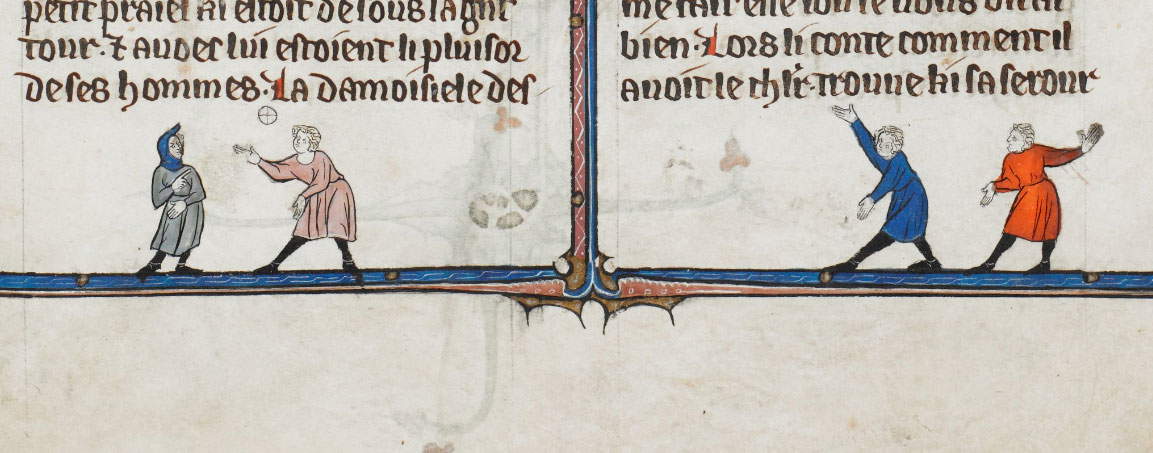

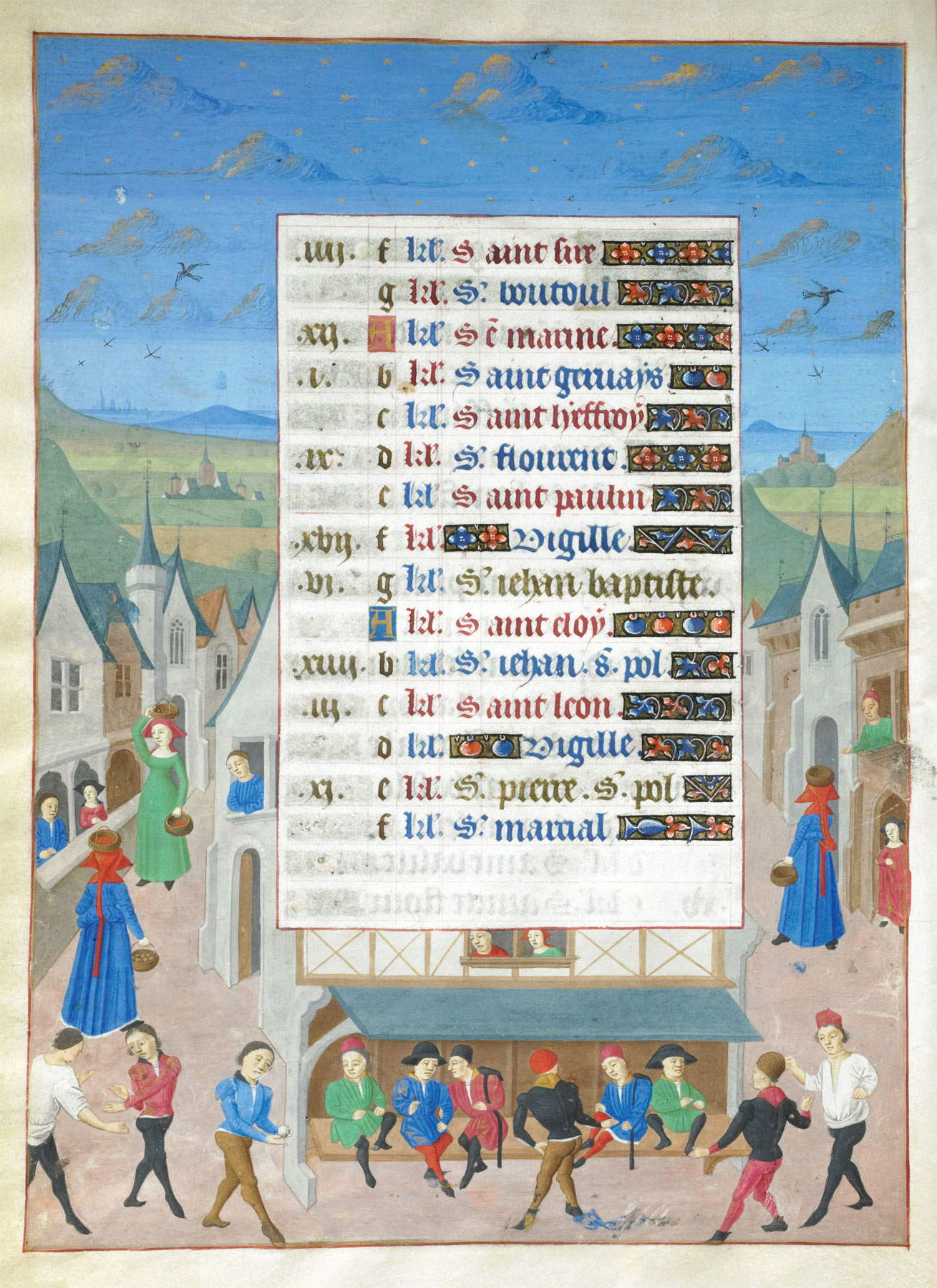

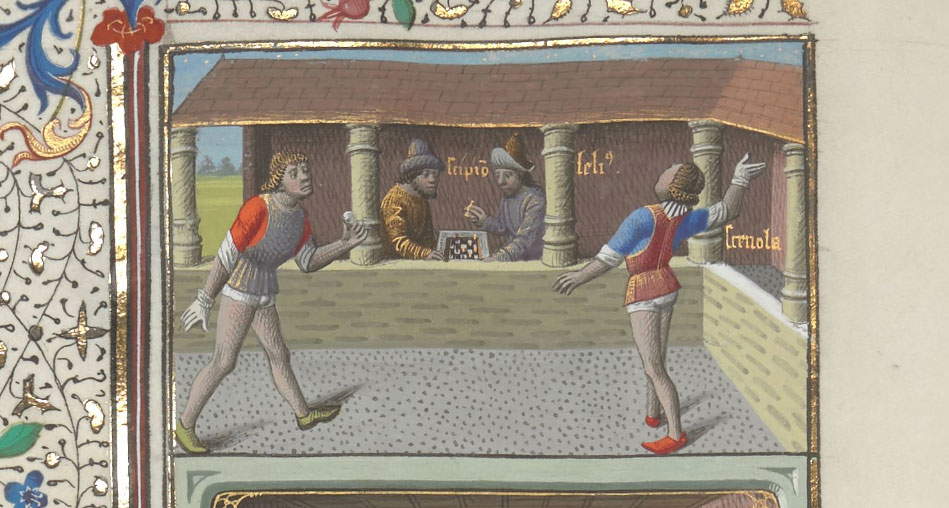

In the history of art there is also a long series of illustrations of jeu de paume first and tennis later, from quite ancient times: the earliest known attestations are those found in illuminated manuscripts. In the manuscript Royal MS 20 D IV, preserved in the British Library in London and in which is found the cycle known as Lancelot du Lac, which recounts the exploits of Lancelot, folio 207v bears an illustration in which four players are seen, one of whom is serving the ball with the palm of his hand and the other two are waiting in reception. Another illustration is found in the Book of Hours illuminated by a Franco-Flemish artist in the first half of the 14th century, now at the Walters Museum in Baltimore (MS. W88, folio 59v): in this case we see the players with gloved hands. In contrast, a game with plenty of spectators is the one illustrated in the Book of Hours of Mary of Burgundy, a work from about 1450 preserved at the Musée Condé in Chantilly, France, where we see a game of jeu de paume taking place in the context of a market. In the same period appears the first depiction of a covered court, whose origin is referred by Heiner Gillmeister to the cloisters of abbeys: it is found in Harley manuscript 4375 (folio 151v) in the British Library, where the Valerius Maximus is contained in the translation of Simon de Hesdin and Nicholas de Gonesse.

To see the first modern tennis match we have to wait until 1538: in a painting by the Flemish Lucas Gassel (Helmond, 1490 Brussels, 1568) we finally see a match where players hold rackets for the first time. The painting, depicting Episodes from the story of David and Bathsheba, is part of the remarkable collection of artworks on the theme of tennis at the International Tennis Hall of Fame in Newport, USA, where, moreover, in mid-2021 the collection of artworks on tennis collected by former tennis player and sports journalist Gianni Clerici (who is also the author of a rich publication on the subject, Tennis in Art, written together with art historian Milena Naldi) also arrived by donation. In Gassel’s work, of which further versions are known, the biblical story of David and Bathsheba is set within a Renaissance palace and its gardens: in the lower part we notice two men climbing a staircase and heading toward King David (he is the one wearing the crown), who receives from a kneeling emissary a letter from Bathsheba. Further back we see a tennis court where two players are facing each other in a match: the ball is in the air, the players are holding their rackets, and the two halves of the court are separated by the rope, which, as mentioned, is the forerunner of today’s net. Gassel’s painting dates from a time when tennis had become very much in vogue in European courts: the Mantua case cited at the beginning is a clear example.

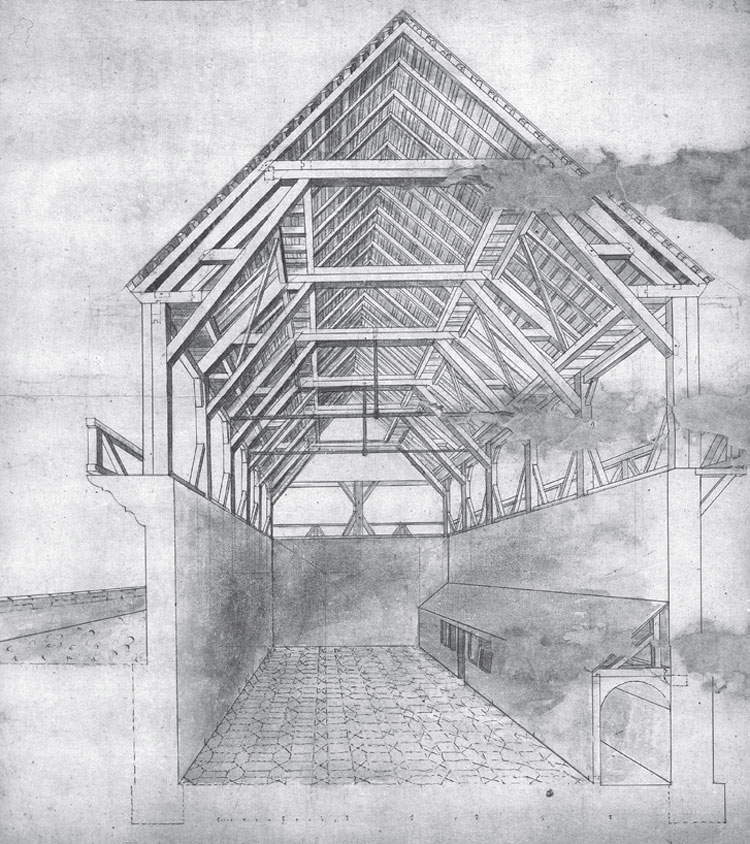

Other images of the game of tennis are recorded in the sixteenth century. For example, in the Emblemata (a book of emblems, i.e., allegorical images accompanied by texts) by the Hungarian humanist János Zsámboky (Trnava, 1531 - Vienna, 1584), also known by his Latin name Johannes Sambucus, we see what is perhaps a training session because there are two players on one side and one on the other holding two rackets (perhaps the coach: it is the completely unusual arrangement of the players that suggests that perhaps this is a training moment). Again, a 1627 drawing by Heinrich Schickhardt (Herrenberg, 1558 Stuttgart, 1635) shows us what a playing court must have looked like, the Ballhaus in Stuttgart built in 1560, and which had not known substantial modifications at the time it was designed by Schickhardt.

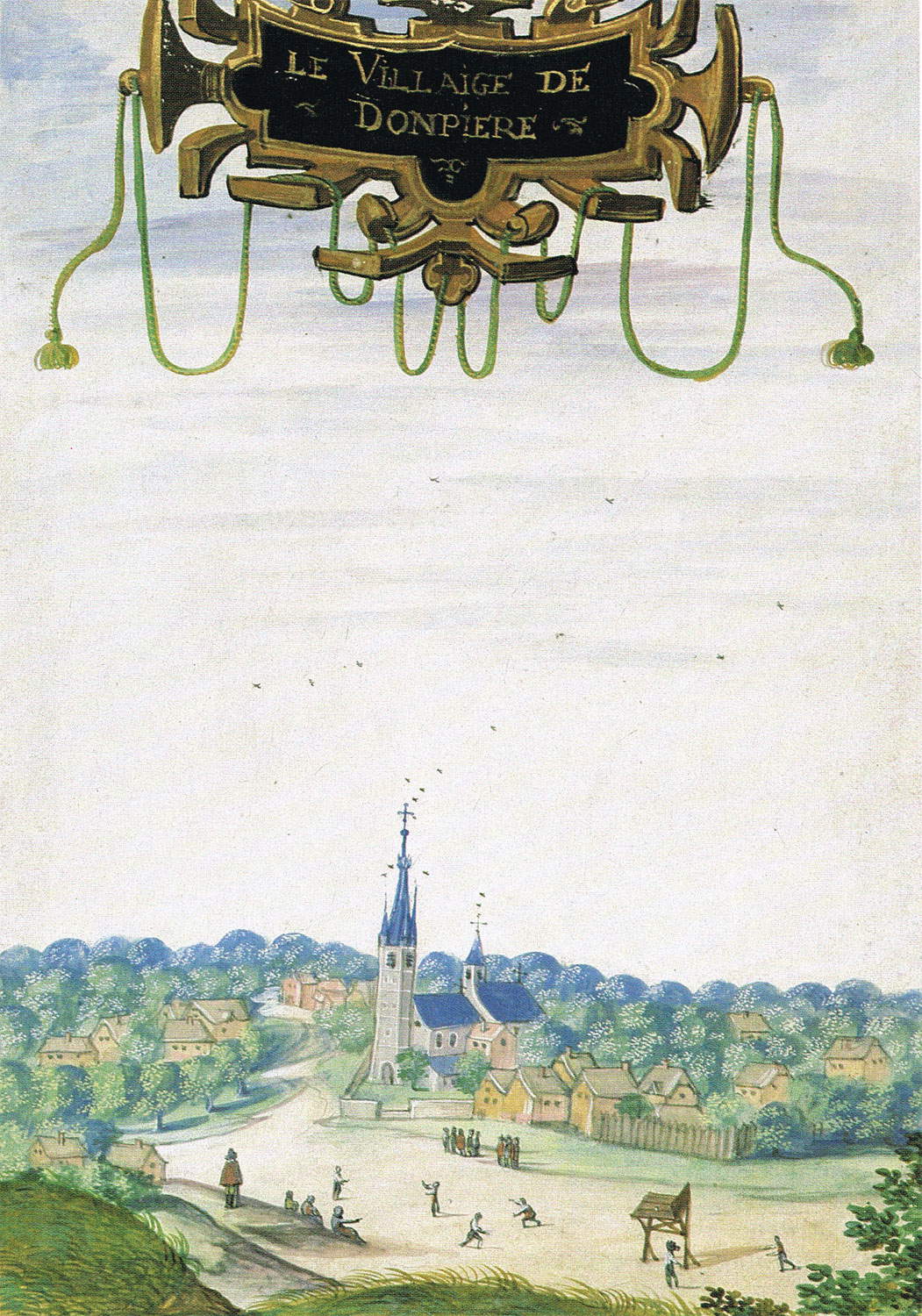

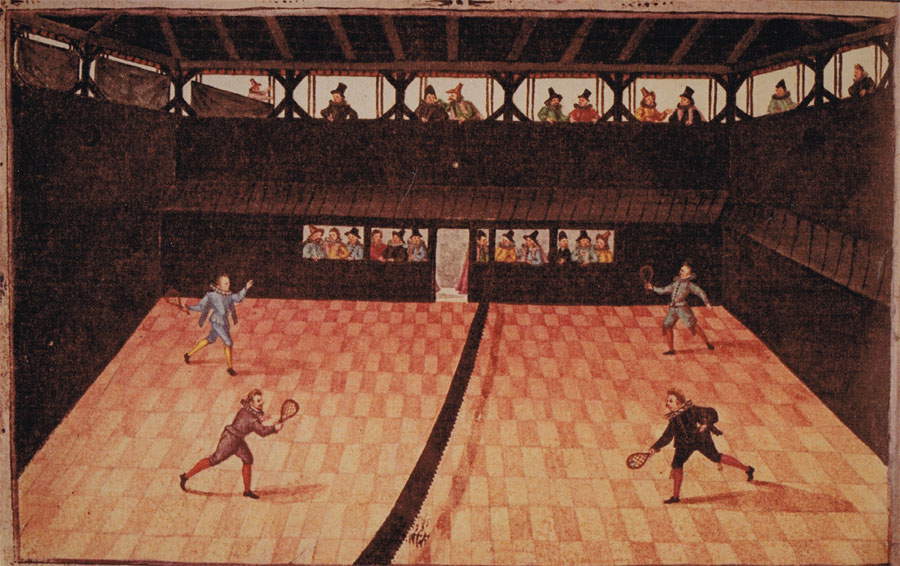

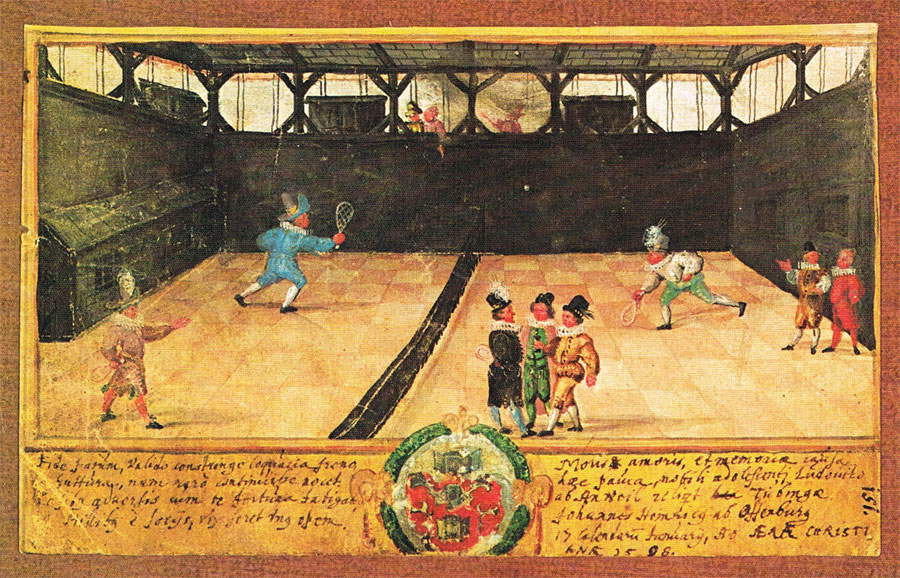

Another interesting depiction of a tennis match, this time in an open field in the countryside on the edge of the village of Dompierre-sur-Helpe, is by the Frenchman Adrien de Montigny (? - 1615), known to have been the author of some 2.500 watercolors (counting only the known ones) to illustrate the Albums de Croÿ, a vast collection of watercolors depicting all the landscapes, towns, villages, forests, and rivers that were part of the property of Charles III, Duke of Croÿ, who commissioned the work. We then witness, near the village nestled in dense forest, a participatory tennis match, with even some spectators. There is, on the other hand, much more audience in an illustration from the same period (Montigny’s watercolor is from 1598), a scene from Duke Augustus of Brunswick’s Stammbuch, a work from 1598, which is set in a kind of 16th-century “Wimbledon,” namely the Ballhaus of the College of Tübingen in Germany, where four players face each other in a doubles match, watched by a large audience. The same playing field, recognizable by its hexagonal windows and checkered floor, is seen in another 1598 illustration from Johann Heinrich von Offenburg’s Stammbuch.

By contrast, one of the earliest close depictions of a roped racket (perhaps the first ever) appears in a drawing by Germain Le Mannier (active from 1537 to 1560) depicting the future King Charles IX of France at the age of two, in 1552: in the drawing, little Charles Maximilian of Orleans holds a small tennis racket in his hands, foreshadowing what would become a great passion of his in the future. This is not the only portrait of a young future ruler with a tennis racket: an Italian example is preserved at the Pinacoteca di Palazzo Mansi in Lucca, where a portrait of Federico Ubaldo Della Rovere, who was duke of Urbino between 1621 and 1623, is kept, where the artist, probably Alessandro Vitali (Urbino, 1580 - c. 1640), captures the little prince standing with racket and ball. In one of the inventories of the Pesaro Palace from where the painting comes, the work is described as follows: “retracted sig[no]r Prince fel[ice] m[emori]a standing while putto, bale in hand, walnut frames.” In the same vein, mention can be made of a portrait of a page holding a racket and ball, which went to auction at Sotheby’s in 2014: it is a painting from 1558-1560, by the circle of Sofonisba Anguissola, where a child, dressed in the fashion of the time, is depicted with the two instruments symbolic of sport.

Tennis, or pallacorda as it is known, had become, by the second half of the 16th century, so popular that it it had even entered mythology. Literally: scholar Alessandro Tosi, in an article published in Nuncius in 2013, points out that, after the publication of Scaino’s treatise, the poet Giovanni Andrea dellAnguillara (Sutri, 1517 - 1572) adapted, in a way, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, in a translation where the episode of Hyacinth’s death, which occurred as a result of a discus-throwing contest (according to the myth, Hyacinth died because the jealous Zephyrus, god of the west wind, deflected the trajectory of the discus thrown by Apollo so that it fatally struck the young man beloved by the god of poetry), is placed, in contrast, in the middle of a game of the “racket game.” Giovanni Andrea dell’Anguillara’s modern adaptation was appreciated to the point of directing artists’ choices: we see it even two centuries later, in a well-known painting by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo kept at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, where the Venetian artist depicts the fatal tennis match.

From the mid-sixteenth century onward, therefore, tennis would no longer be only the subject of illustrations of scenes of everyday life but would also enter visual texts that, Tosi writes, "in the narrative framework provided by mythology or complex symbolic imagery, presented elegant allegories in which the allusion to the game became a moralizing element in the Theatrum vitae humanae, between Virtus and Voluptas." Indeed, reference to the game of tennis as a symbol of vanitas is very frequent in seventeenth-century art, signifying that in life carefree moments are destined to fade away. Tennis, in short, had already become a popular sport throughout Europe.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.