What do we know about Leonardo da Vinci’shomosexuality? Can we say with certainty that the great Tuscan genius was gay? If the reader is looking for an immediate answer, then the answer is: no, we cannot have documentary evidence that Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519) was homosexual (or rather: sodomite, for that was the term in use at the time; “homosexual” is instead a contemporary term), since, sodomy being at the time a very serious crime, punishable with decidedly severe penalties, it is quite improbable to imagine that we could find, in the vincian’s albeit numerous writings, some sort of coming out, black on white. This, then, is the quickest answer that can be given. However, the fact that Leonardo da Vinci left no written traces from which his sexual tastes can be inferred with palpable clarity does not, however, exclude the possibility of working on the clues to try to reconstruct Leonardo’s relationship with people of the same sex. This article is not intended to give answers, but simply to try to outline what we know on the subject.

Meanwhile, it is necessary to specify that the discussion of Leonardo’s homosexuality has impassioned few art historians, and most of those few who have tackled the subject have done so mainly to try to deny or downplay the idea of a Leonardo oriented toward people of his own sex, with an attempt, conversely, to attribute to him relationships with women (on the basis, however, of very weak footholds, as will be seen below). Among the rare art historians who have made mention of the subject in larger monographs devoted to Leonardo’s artistic output, it will be necessary to mention at least Frank Zöllner, one of the foremost experts on Leonardo, who in his monograph published by Taschen reports, in the section devoted to the early phase of his career, that Leonardo “already as a very young man was known for his homosexual inclinations (a crime at the time)” and that these inclinations “in the 16th century were accepted almost as an obvious feature of his portrait of genius.” We will return later in the article to the documents that motivate and support Zöllner’s two sentences: however, we can begin more broadly by recalling that the modern discussion of Leonardo’s homosexuality originated with Sigmund Freud. The father of psychoanalysis, in 1910, wrote a meaty essay entitled Eine Kindheitserinnerung des Leonardo da Vinci (“A Childhood Recollection of Leonardo da Vinci”) centered on a note that Leonardo da Vinci wrote on one of the sheets (the verso of number 186) of the Codex Atlanticus, where the artist recalls a dream he had as a child. “In my earliest recollection of my childhood,” Leonardo da Vinci writes, “it seemed to me that, I being in the cradle, a kite came to me and opened its mouth with its tail, and many times beat me with its tail inside my lips.” In essence, Leonardo recalls having a dream in which a kite repeatedly struck his mouth with its tail. According to Freud, the kite (which for the Austrian psychoanalyst is nevertheless a “vulture”: in fact, he had relied on a mistranslation into German from the original Leonardian for his essay) could be a clear reference to oral intercourse, which could be the starting point for trying to derive the artist’s homosexuality from his behaviors. These would include his strong attachment to his mother, his habit of surrounding himself with young pupils, and the constant presence in his drawings and paintings of androgynous subjects.

These are, however, indications that in themselves not only provide no evidence, but also do not constitute useful clues unless supported by other evidence. Every artist who kept a workshop at the time was constantly surrounded by young pupils, and the androgyny of many Leonardian subjects could be explained on cultural grounds. On the latter issue, it is interesting to report, just as an example, the idea of one of Leonardo’s leading scholars, Edoardo Villata, who in 1997 devoted an extensive essay to the Louvre’s Saint John the Baptist, a work that, by virtue of its marked sensuality, is often called into question for attributing a homosexual orientation to Leonardo on the sole basis of the saint’s appearance. Villata acknowledges that the strongly and overtly sensual character of Saint John the Baptist is one of the aspects most emphasized by scholars: “in no other work, perhaps,” the scholar writes, “does Leonardo seem to give in to the complacency of exhibiting a youthful body of pulsating vitality, whose flesh, almost gilded by the ’lume particulare’ which is reflected on it as on a smooth translucent surface, lies in soft folds and, together with the ’beautiful and curly ringed hair, of which Lionardo took great delight,’ gives the figure an indeterminate feminine character.” To what is such an appearance due? Villata rejects, on the one hand, the idea that in St. John we can perceive “the effusion of a homosexual elderly man” (a thesis supported by another great Leonardo scholar, Martin Kemp), and on the other hand, also an interpretation in a neo-Platonic key, with alleged meanings that refer to the thesis of the androgyny of the original and perfect man: according to the scholar, the conturbance of St. John, which we find in other works of Leonardo (such as Leda and the Swan: we do not, however, perceive the same erotic charge from it due to the fact that the Leonardo image has come down to us only through copies and reproductions) is peculiar to figures that make themselves bearers of “an all too disconcerting naturalness seen first and foremost as generative and metamorphic power (but also as necessity),” and is explained “on the basis of his theoretical speculation.” The idea that the sensuality of certain of his subjects is therefore to be traced back to Leonardo’s highly inquisitive attitude may not convince many, but it is enough to give the reader an idea of how complicated, if not impossible, it is to infer Leonardo’s sexual orientation simply by looking at his works, without taking into account the historical and cultural context in which he operated and especially without taking into account his ideas, which we know extensively thanks to his notes.

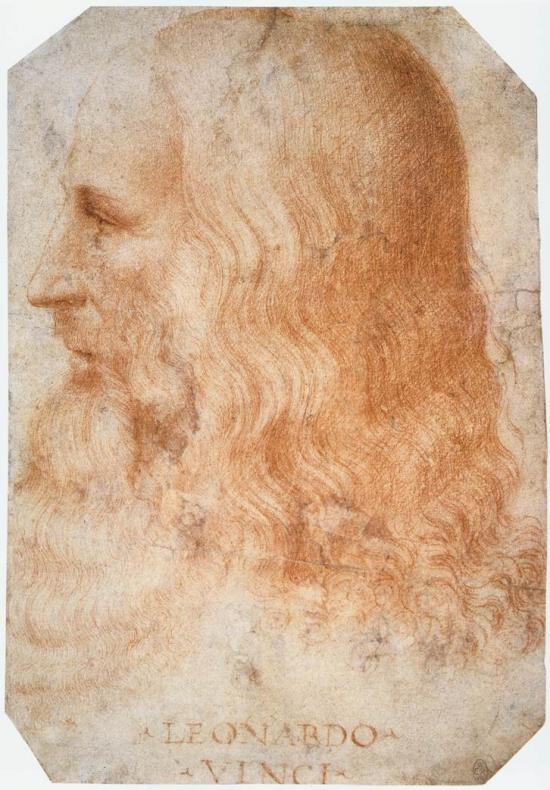

|

| Francesco Melzi, Portrait of Leonardo da Vinci (c. 1510; sanguine on paper, 275 x 190 mm; Windsor, Royal Collection) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Saint John the Baptist (1508-1513; oil on panel, 69 x 57 cm; Paris, Louvre) |

It is therefore necessary to find clues elsewhere, starting with the documents of the time. And in this sense the only document in which there is a definite link between Leonardo da Vinci and the practice of sodomy is a well-known accusation dating from April 9, 1476: Leonardo was 24 years old and accused of having carnal relations with a young man who was prostituting himself, a certain Jacopo Saltarelli, a goldsmith’s apprentice by profession, about seventeen years of age (the affair, which Zöllner has in mind when he writes that the artist’s proclivities were known in fifteenth-century Florence, moreover gave the cue to the 2021 Leonardo TV series for the now already famous gay kissing scene between Leonardo, played by Aidan Turner, and Jacopo, played by Kit Clarke). In 15th-century Florence, there was a magistracy, known as the “Officers of the Night” (active from 1432 to 1502), whose task was to oversee everything that happened, precisely, in the Florentine night: in fact, it was a kind of vice of the time. Citizens who wished to denounce someone for sodomy had at their disposal a “drum” into which they could insert a sheet with the names and surnames of the accused, relying on the fact that the accusation was secret: the delators were required to sign it (this was to obviate the problem of slander), but their names were not revealed to the accused. Historian Martin Rocke, who has devoted an extensive study to the practice of sodomy in Renaissance Florence, has calculated that during the seventy-year period of the Officers of the Night, between 15 and 16 thousand men accused of entertaining homosexual activities were tried, with over 2.400 convictions (an incredibly high number when one considers that, at the end of the fifteenth century, Florence had a population of about 50 thousand, compared to 80 thousand in Venice where a similar magistracy, that of the “Lords of the Night,” operated, and where, however, only 268 convictions for sodomy were issued between 1406 and 1500). In practice, according to Rocke, most of the men of Renaissance Florence had something to do with the Officers of the Night: however, it is necessary to remember that the accusation of sodomy was often used in an instrumental way, as a means of targeting political opponents. Historian Giovanni Dall’Or to has calculated that about 5 percent of Florentine males who lived during the period of activity of the Ufficiali della Notte were convicted of sodomy: a striking figure that highlights how, writes Dall’Orto, "homosexual practice was somehow ’normalized’ and integrated into the male sexual experience of fifteenth-century Florence even for young heterosexuals." Add then the element of the structuring of the sodomitic subculture of Florence at the time exemplified, Dall’Orto again writes, on a “pederastic model” (89.7 percent of the 475 “passives” whose ages can be reconstructed for certain by analyzing the documents were 18 years old or younger, compared to 82.5 percent of the 777 “actives” who were over 19).

Returning to Leonardo, in the indictment sent to the Officers of the Night we read, “I notify you Gentlemen Officers how he is true thing that Jacopo Saltarelli carnal brother of Giovanni Saltarelli, is with him at the goldsmith in Vacchereccia, dirimpetto al buco [drum]: he dresses black of age of 17 years, or about. El quale Jacopo va dietro a molte misserue et consente compiacere a quelle persone richieghono di simili tristizie. Et a questo modo à avere a fare di molte cose, cioè servito parecchie dozine di persone delle quali ne so buon data, et alchuno dirò d’alchuno: Bartolomeo di Pasquino orafo, he is in Vacchereccia; Lionardo di Ser Piero da Vinci, he is with Andrea de Verrochio; Baccino farsettaio, he is from Or San Michele in that street that there are two large workshops of cimatori, which goes to the loggia de’ Cierchi: he has opened workshop again of farsettajo; Lionardo Tornabuoni, dicto il teri: he wears black. Questi ànno avuto a soddomitare decto Jacopo: et così vi fo fede.” On June 7 the final verdict of the trial already arrives: the four defendants (Bartolomeo di Pasquino, Leonardo da Vinci, Baccino farsettaio and Leonardo Tornabuoni) are completely exonerated. There are two elements, however, that do not allow us to clarify whether the charges were true. The first, is that the accusation was anonymous, and for that reason had to be invalidated, since the Officers did not admit anonymous complaints. The second, is that among the four characters was a certain Leonardo Tornabuoni, a member of one of the most illustrious families in Florence at the time (suffice it to say that Lorenzo the Magnificent was the son of a Tornabuoni, Lucrezia): we can therefore assume that we are dealing with a case of a denunciation instrumental in targeting a prominent personage. And Leonardo was somehow able to take advantage of the circumstances of the accusation to escape conviction.

One could then probe the relationships Leonardo had with his pupils: his entourage, as is well known, was almost entirely male. The attentions of scholars have particularly focused on the relationship between Leonardo and the painter Gian Giacomo Caprotti (Oreno, 1480 - Milan, 1524), whom the Tuscan genius nicknamed “Salaì” (the name of a devil in Luigi Pulci’s Morgante ) because of his character (Leonardo himself described him as a “thief, liar, obstinate, greedy” in a note in which he recalled how Caprotti had robbed him of some coins he kept in his bag: the fact dates back to 1497, seven years after Salaì, only ten years old, had entered Leonardo’s workshop). Yet despite the roughness of his character, Salaì was a boy of beautiful appearance, as Vasari also recounts in his Lives (“Prese in Milano Salaì milanese per suo creato, il qual era vaghissimo di grazia e di bellezza, avendo begli capegli, ricci et inanellati, de quali Lionardo si dilettò molto et a lui insegnò molte cose dell’arte”), and Leonardo was always attached to him, so much so that he frequented him for many years, and in 1519, when he dictated his last will, he left him half of his garden in Milan (where Caprotti, by the way, had already built a house). From the moment Leonardo had taken him into his workshop, he never parted with him until the year of his move to France, 1517: the Salaì followed him to Amboise, but stayed little with the master (he certainly was not with Leonardo when the genius disappeared). There is no clear evidence of a homosexual relationship between the two: yet, writes Dall’Orto again, who also put together the most comprehensive work on Leonardo da Vinci’s homosexuality, “if one did not assume a relationship between Leonardo and Salaì, one would not understand why the artist insisted for so many years on keeping him by his side as a boy and servant,” given his idle and lying character. Dall’Orto also points out that while it is a given that Salaì entered Leonardo’s workshop in 1490, mentions of him in the genius’ notes do not appear until 1494: “if fourteen years old seems decidedly young for a partner to us today,” the scholar writes, “Leonardo was a child of his time, and those were times when a twelve-year-old girl could be given in marriage to a made man, even with the blessing of the Church.” Consequently, even without wanting to imagine that Leonardo had relations with a ten-year-old boy, the age of fourteen was not considered disreputable to the morals of the time.

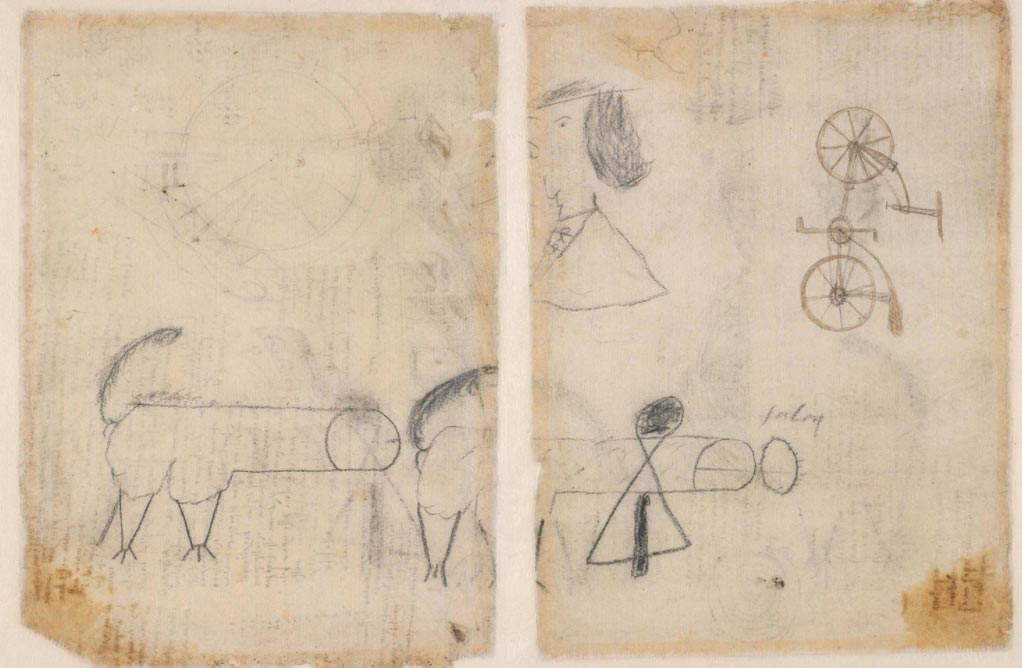

The fact that the Salaì might have been the object of Leonardo’s attentions is, moreover, suggested to us by two sheets of the Codex Atlanticus, 132v and 133v, on which there are some scribbles by Leonardo’s pupils, one of which depicts the very famous bicycle that so many people are now familiar with. However, when books or newspapers reproduce 133v they are wont to cut out only the portion with the bicycle without showing what the students of the Tuscan genius drew beside it: thus we see two large penises, provided with legs, marching toward an orifice on which is inscribed “Salaì.” Of course, this is not proof (any male, even today, will have happened to be accused of homosexuality in goliardic circles), but it is nonetheless a fact that Salaì turns out to be the only pupil of Leonardo for whom a similar joke is attested.

|

| The gay kiss between Leonardo da Vinci (Aidan Turner) and Jacopo Saltarelli (Kit Clarke) in the RAI series 2021 |

|

| Folios 132v and 133v of the Codex Atlanticus. |

Also to the goliardic milieu of Leonardo’s workshop can be traced the recently discovered drawing of theIncarnate Angel to which was added (it is not known by whom, whether by Leonardo or some of his pupils) a conspicuously erect member, which in any case in itself proves nothing (Leonardo also left us drawings of heterosexual coitus), except that he was probably not as disinterested in sex as some scholars have implied. This is not, however, an isolated case: the Milanese painter Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo (Milan, 1538 - 1592), in his Treatise on Painting, recalls some drawings, “one of which was beautiful boy, co’l membro in fronte e senza naso, e con un’altra faccia di dietro della testa, col membro virile sotto il chento, e l’orecchie attaccate a i testicoli, le quali due teste havevano le orecchie di fauno; e l’altro mostro aveva in cima del naso il membro.” It will be worth mentioning, however, how Leonardo’s disciples also included Francesco Melzi (Milan, 1491 - Vaprio d’Adda, 1570), a young scion of a noble family, who lived in Leonardo’s house from 1510 until his death (he also followed him to France), and who was named heir to his movable property: officially he was his assistant, but there are those who speculate that cohabitation may motivate a relationship between the young man and the master.

Again Lomazzo, in his Book of Dreams, imagines a “reasoning” (i.e., a dialogue), the fifth in the book, between Phidias and Leonardo da Vinci, which contains an explicit reference to homosexual practices that the artist allegedly engaged in with Caprotti. Phidias asks Leonardo, referring to the Salaì, “Did you play to him forsi the game, which the Florentines so love, of dretto?” Leonardo answers affirmatively, “And how many times! Consider that he was a beautiful young man, and maximally in his fifteenth year.” Phidias replies, “Are you not ashamed to say this?” And Leonardo: “How ashamed? It is not a thing of greater praise, among the virtuous, than this; and that he is true I will prove to you with very good reasons. Know that masculine love is the work only of virtue, which, by joining men together, with diverse affections of friendship, so that from one tender ettà come in the virile more fortified friends.” These are the elements that led Zöllner to assert that in the 16th century Leonardo’s homosexuality was taken for granted.

|

| The incarnate angel, preserved at the Rossana & Carlo Pedretti Foundation in Lamporecchio |

In conclusion, while it is true that there is no granitic evidence to establish that Leonardo was a sodomite (everyone will make up his own mind based on the above), there is also no evidence to attribute relationships with women to him. Many have tried, but always with shaky footholds, far weaker than those with which we try to reconstruct a trace of Leonardo da Vinci’s homosexuality. The most recent theory has it that Leonardo had been accompanied by a courtesan, a certain "Cremona,“ named after the city from which she came. On what basis was this asserted? This elusive ”Cremona" was completely unknown until 1982, when an edition of some writings by one of the greatest artists of neoclassicism, Giuseppe Bossi (Busto Arsizio, 1777 - Milan, 1815), was published. Bossi, a great admirer of Leonardo, wanting to consolidate the idea that Leonardo “loved pleasures,” brings as proof, the artist writes, “a note of his concerning a courtesan called Cremona, a note communicated to me by an authoritative person. Nor would it have been possible, that he had so thoroughly known men, and human nature to represent it without, by long practice, tinging himself somewhat with human weaknesses.” On the basis of this note by Bossi, some scholars, such as Carlo Pedretti and Charles Nicholl, have tried to attribute to Leonardo an affair with one of his courtesans: in other words, the Vincentian, in order to know human nature so thoroughly, had to know carnal pleasures with the opposite sex as well. Beyond the fact that a similar assumption could be made to prove the opposite thesis as well, one understands how a writing by an author who lived three centuries after Leonardo da Vinci, and who does not even mention the name of his source, is such a weak piece of evidence that it cannot be taken into any consideration when trying to prove Leonardo da Vinci’s orientation.

Nicholl tried to elaborate on this thesis: in his view, Bossi’s source may have been Carlo Amoretti, a librarian at the Ambrosiana in Milan who was known to have made copies of several Leonardo sheets. And of the fact that it was also necessary to search at the Ambrosiana (knowing, moreover, that probably much of Leonardo’s patrimony had disappeared during the Napoleonic spoliations) Pedretti was also convinced, who in 1996 published an essay in which he recalled how, in Rome (where he stayed between 1513 and 1516), the artist had set up a laboratory to do some experiments with mirrors: however, according to Pedretti, Leonardo’s intentions would have been anything but scientific. According to Pedretti, in order to have his models pose in this workshop, Leonardo would have used a wig: the idea is fortified by a note in his own hand in which, referring to the wig, he says “Questa si po’ levare e porre sanza guastarsi,” as if, Pedretti writes, “Leonardo himself had it made for his model (what if it were La Cremona?).” Pedretti also notes that the records of the time include a certain “Maria Cremonese” who may have been a prostitute. Of course, it is plausible that Leonardo frequented a harlot, who could also occasionally lend herself to pose for him. But this still offers no evidence about his sexual tastes.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.