"Today I worked even more: five canvases, and tomorrow I plan to start a sixth; we are doing quite well, then, although everything is very difficult for me to do. These palm trees give me hell, and then the motifs are extremely difficult to reproduce, to transfer to canvas; it’s so thick everywhere; it’s delightful to look at; you can walk indefinitely under the palm trees, the orange and lemon trees, and even under the beautiful olive trees, but when you’re looking for subjects it’s very difficult. I would like to do certain orange and lemon trees silhouetted against the blue sea, I can’t find them the way I want. As for the blue sea and sky, it is impossible. However, every day I add and discover something I hadn’t been able to see before. These places seem to be made especially for en plein air painting. I feel particularly excited by this experience and, therefore, I think of returning to Giverny later than planned, even if your absence disturbs my serenity" (Bordighera, Jan. 26, 1884).

“I work like a madman on six canvases a day. I struggle a great deal, for I cannot yet grasp the tone of this country; sometimes I am frightened by the colors I have to use, I am afraid of being terrible, and yet I am still well below; it is atrocious light” (Bordighera, Jan. 29, 1884).

So wrote Claude Monet (Paris, 1840 - Giverny, 1926) to Alice Hoschedé, his second wife after Camille’s untimely death at the age of only thirty-three in 1879. Claude for Alice was also her second husband, as her first was Ernest Hoschedé, Monet’s collector and friend.

Closing the parenthesis on the past romantic ties of both of them, it is clear from these letters, in addition to Claude’s great love and strong esteem for Alice, a kind of anxiety about the artist’s difficulty in rendering on canvas those extraordinary colors he saw in reality on the Ligurian Riviera. He was fascinated, almost hypnotized by these landscapes, by the rich variety of greens of the lush vegetation, by the bright colors of the citrus fruits, by the shades of blue that the sea and the sky offered to the eye and that very often changed from day to day, and above all by the light that brightened and reflected on every element of nature. His “fright” determined by the colors faded little by little, and on February 3, 1884, Claude wrote to his Alice, “Now I feel the country well, I dare to put in earth tones and pinks and blues; it is magic, it is delightful, and I hope you will like it,” and a month later, on March 5, 1884, he told her, “I am now painting with Italian colors that I had to have brought from Turin.”

But his awareness that he was “far below the tone” had not abandoned him: only a few days after the last quoted letter, Monet declared to art dealer and friend Paul Durand-Ruel (Paris, 1831 - 1922): “I will perhaps make the enemies of blue and pink cry out a little, because of this splendor, this fantastic light which I apply myself to render; and those who have never seen this country or who have seen it badly will cry out, I am sure, at the improbability, although I am far below the tone: everything is iridescent and flaming color, it is admirable; and every day the countryside is more beautiful, and I am enchanted with the country” (Bordighera, March 11, 1884).

|

| Claude Monet, Self-Portrait (1886; oil on canvas, 55 x 46 cm; Private collection) |

These letters bear witness to the stay that Claude Monet had made in total solitude in Italy, settling in Bordighera, a small village between Sanremo and Ventimiglia, on the western Ligurian Riviera; from here he had had the opportunity to visit nearby villages, including Dolceacqua, and the Val Nervia. It was an extraordinary landscape for him, but he had to become familiar with theintensity of the Mediterranean colors. Until then, in fact, he had never used on his palette the blue tending to purple for the sky and atmosphere, the pink or apricot for the flowers, the emerald green for the sea water: new colors and atmospheres that amazed him, but made him despair for the fear of not being able to represent all this on canvas.

In fact, Ligurian landscapes, especially those of Genoa, had already been discovered by the French painter a few months earlier, when together with Pierre-Auguste Renoir (Limoges, 1841 - Cagnes-sur-Mer, 1919) he had decided to explore the South in search of new inspiration. At the end of 1883, therefore, the two artists had come to Genoa via Marseille, but as a result of both realizing that their style and the subjects they intended to depict had become different, they had abandoned the idea of staying together in the same places, so they had returned to French soil, not before stopping in L’Estaque, a village in southern France, to visit their friend Paul Cézanne (Aix-en-Provence, 1839 - 1906). The trip south had also been dictated by market necessity, since since 1882, i.e., at the conclusion of the seventh exhibition of the Impressionists, Monet had decided not to participate in any Impressionist exhibition or Salon, so the dissemination of his works was totally tied to the world of critics and collectors; however, in the same year as the trip with Renoir, his solo exhibition was held in March at the Durand-Ruel Gallery, at Boulevard de la Madeleine, 9.

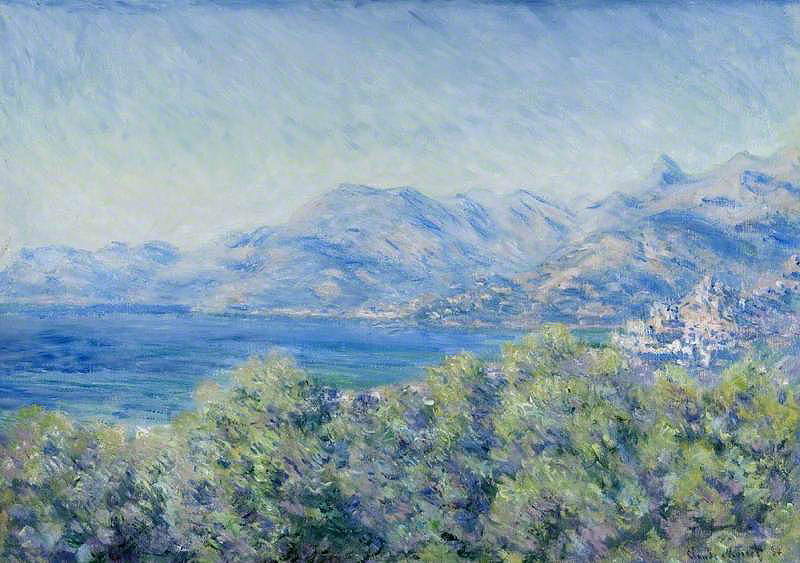

Despite his tireless work, reaching up to six canvases at once, Monet had completed about fifty paintings in and around Bordighera. In the Ligurian village he had had the opportunity to admire and visit the Moreno garden, commissioned in about 1830 by Vincenzo Moreno, a wealthy oil merchant from Bordighera, who had begun planting the seeds of many exotic species; by the 1880s the garden had become internationally famous for the great variety of vegetation it held and was therefore a destination for visits by literati, artists and travelers. Inspired by the wonder of this place, now part of the Great Italian Gardens and selected as one of the most beautiful gardens in Liguria, the artist had depicted on canvas three spots in the park, still recognizable now if you go inside: the paintings made in 1884 set here are Views of Ventimiglia, Study of Olive Trees and Garden at Bordighera. Morning Impressions. The former is kept at the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow and depicts precisely a vantage point over the town of Ventimiglia, bathed by the sea and lit by the sun; in the foreground is the lush vegetation created using shades of green with touches of purple. Study of Olive Tre es is part of a private collection and is dedicated to large, centuries-old olive trees with trunks that seem to take a bow. The last painting of the trio, now housed in theHermitage in St. Petersburg, is also the brightest and most nuanced: palm trees illuminated by the morning sunlight act as a curtain to a church bell tower that can be seen in the center of the canvas; in the background the sea can be glimpsed. Observing this work seems to be right in the midst of the thick and rich vegetation of the garden.

|

| Claude Monet, View of Ventimiglia (1884; oil on canvas, 65.1 x 91.7 cm; Glasgow, Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum) |

|

| Claude Monet, Study of Olive Tre es (1884; oil on canvas, 73 x 60 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Claude Monet, Garden at Bordighera (1884; oil on canvas, 65.5 x 81.5 cm; St. Petersburg, Hermitage) |

Still set in the Moreno garden is the work Le Ville a Bordighera, made in the same year and preserved at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. On the right of the painting is the architectural component, while plants and palm trees return to the foreground. In the background, silhouettes of mountains can be glimpsed in the distance. In fact, this painting was not made in Bordighera, but in the Giverny workshop, referring to a smaller canvas executed there: the latter bears the same title, but is kept at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. Again, Monet intends to emphasize the great importance of the colors and light of these places and oftenusesforeshortening to emphasize the totalizing aspect of the composition. The painting in the Musée d’Orsay was made as a decorative panel for the living room of the painter Berthe Morisot (Bourges, 1841 - Paris, 1895), who described herself as thrilled to have begun to enter into intimacy with her Impressionist colleagues.

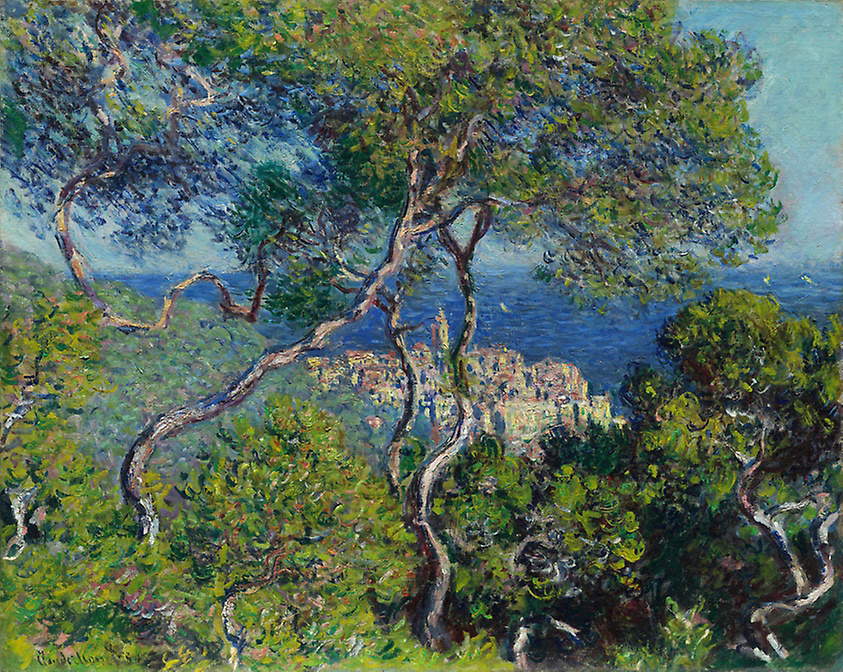

A further panoramic view is presented in Bordighera, an oil on canvas housed at theArtInstituteof Chicago. The predominance of nature and vegetation is again emphasized here, placing in the foreground trees whose foliage occupies almost the entire painting and whose trunks twist to meet at the top. The village is placed in the distance, in foreshortening, between the green of the plants and the very intense blue of the sea. Therefore, the fundamental colors for these compositions continue to be blue, green declined in tones and undertones and shades between yellow and white to achieve that luminosity so much feared by the artist.

|

| Claude Monet, Ville a Bordighera (1884; oil on canvas, 115 x 130 cm; Paris, Musée d’Orsay) |

|

| Claude Monet, Ville a Bordighera (1884; oil on canvas, 73 x 91 cm; Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara Museum of Art) |

|

| Claude Monet, Bordighera (1884; oil on canvas, 65 x 80.8 cm; Chicago, The Art Institute of Chicago) |

|

| Claude Monet, The Valley of Sasso. Sun Effect (1884; oil on canvas, 65 x 81 cm; Paris, Musée Marmottan Monet) |

|

| Claude Monet, The Castle of Dolceacqua (1884; oil on canvas, 92 x 73 cm; Paris, Musée Marmottan Monet) |

|

| Claude Monet, The Old Bridge over the Nervia at Dolceacqua (1884; oil on canvas, 65 x 81 cm; Williamstwon, Sterling & Francine Clark Art Institute) |

During his stay on the Ligurian Riviera, the artist had also had the opportunity to explore the surroundings of Bordighera, such as Sasso, to whose valley Monet dedicated a painting, now housed at the MuséeMarmottanin Paris: this is La Vallée de Sasso, effet de soleil (“The Valley of Sasso, Sun Effect”). Central to this painting is still the rich presence of palm trees and plants, among which a squarely shaped building stands out. The entire composition is then fully illuminated by the sun’s rays, which make the colors imprinted on the canvas more brilliant. In 2017, a proposal had been made by the two mayors of Bordighera and Dolceacqua to bring back for exhibition in the summer of 2019 two of the canvases that Monet had executed in these places: one was indeed La Valle di Sasso, while the other work in question was Le Château de Dolceacqua (“The Castle of Dolceacqua”). The Castle of Dolceacqua, also known as the Castle of the Dorias, towers over the oldest part of the Ligurian village and, together with the PonteVecchio below, creates a picture-postcard landscape that continues to captivate many tourists exploring the Nervia Valley, just as in the 1880s it had enchanted the great Impressionist artist, so much so that he portrayed it in his paintings. Masterpieces in which Monet had focused on this fairy-tale and enchanted place: in the center was always the bridge with its characteristic very pronounced arched shape that divides the village into two parts because of the passage of the Nervia stream. The viewpoints from which Monet had painted his works are clearly recognizable: The CastleofDolceacqua, housed at the Musée Marmottan, shows a broader, more centered perspective and darker tones; The Old Bridge over the Nervia at Dolceacqua, on view at the Sterling and Francine ClarkInstitutein Massachusetts, shows in the foreground, from bottom to top, the Ponte Vecchio with its side steps and all around confusing patches of green, lighter in color than the previous one. What had amazed him was this “bridge that is a jewel of lightness,” as he called it in his writings of those years.

On the Ligurian Riviera Monet found sensational landscapes and gave art history his most vivid and intense paintings, managing to capture, although in his words “far below the tone,” the strong chromaticism typical of those places.

Reference bibliography

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.