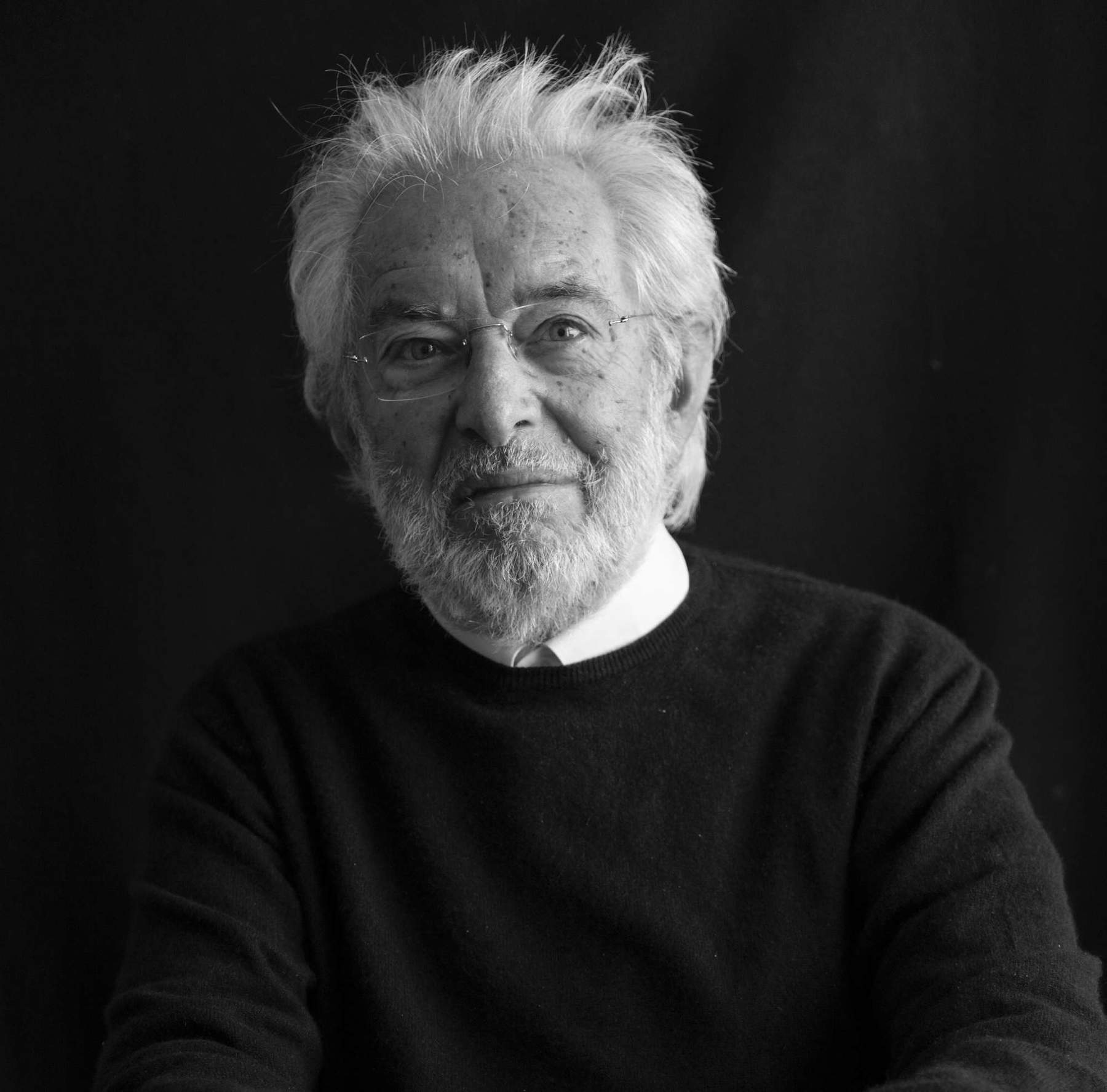

Mimmo Jodice, born in Naples in 1934, is one of the most representative figures in Italian and international photography. His work, now the focus of the exhibition Mimmo Jodice. The Enigma of Light hosted at Udine Castle (from April 5 to Nov. 4, 2025, curated by Silvia Bianco), spans more than 50 years of visual investigation, ranging from technical experimentation to the poetic telling of places and memories. His black-and-white images, permeated by metaphysical silence and evocative light, transform reality into vision, space into suspension, and time into reflection.

Jodice’s is an auteur photography that stands out for its balance between form and intuition, for its ability to evoke profound emotions through the apparent simplicity of chiaroscuro. Naples, his hometown, is the protagonist of many of his works: not just a setting, but a lens through which to observe the complexity of living, made up of popular traditions, collective pain, and historical stratifications. Jodice is a photographer who has made the darkroom his inner laboratory, who has photographed absence to talk about presence, and who continues to teach us to see “well,” as he says, only if light properly caresses forms. Here, in 10 points, is how to enter the enigmatic and visionary world of Mimmo Jodice.

Light, for Mimmo Jodice, is not simply a means of making visible what is in front of the lens, but a poetic and spiritual substance. It is through light that the artist shapes the image, reveals its hidden soul, but above all constructs a universe that transcends the real. Light, particularly the light that gently caresses surfaces, is the element that draws forms, brings out their details and, paradoxically, suggests what remains invisible.

In Mimmo Jodice’s works, chiaroscuro becomes expressive language: shadow is not lack, but eloquent presence; light is not exposure, but revelation. It is a mental, inner light that tells more than it shows. Jodice has been able to translate the simplicity of natural light into a powerful artistic tool, capable of generating metaphysical reflections. His shots do not “document,” but evoke atmospheres dense with silence and meaning. It is precisely in this enigma, in this play between the visible and invisible, that lies the heart of his poetics. “Seeing well. The excellent result can only be had if there is light that properly caresses the shaping of forms”: so says the artist himself.

Mimmo Jodice’s career is punctuated by an inexhaustible drive for experimentation. From the 1960s, he began to question not only the subject to be photographed, but the medium itself: photography. The darkroom becomes his laboratory of visual alchemy, the place where reality is disassembled and reassembled according to a personal, poetic logic. Jodice manipulates negatives, superimposes images, seeks in black and white not a faithful rendering of reality, but its reinvention.

For him, every image is the result of a long process made of observation, waiting and interpretation. The moment of the shot is only one phase. The work in the darkroom is the soul of his creation: there the transformation of the image into vision takes place. His is a method that combines technical rigor and expressive freedom. Jodice, through his research, shows us how photography can be meditation, introspection, visual philosophy.

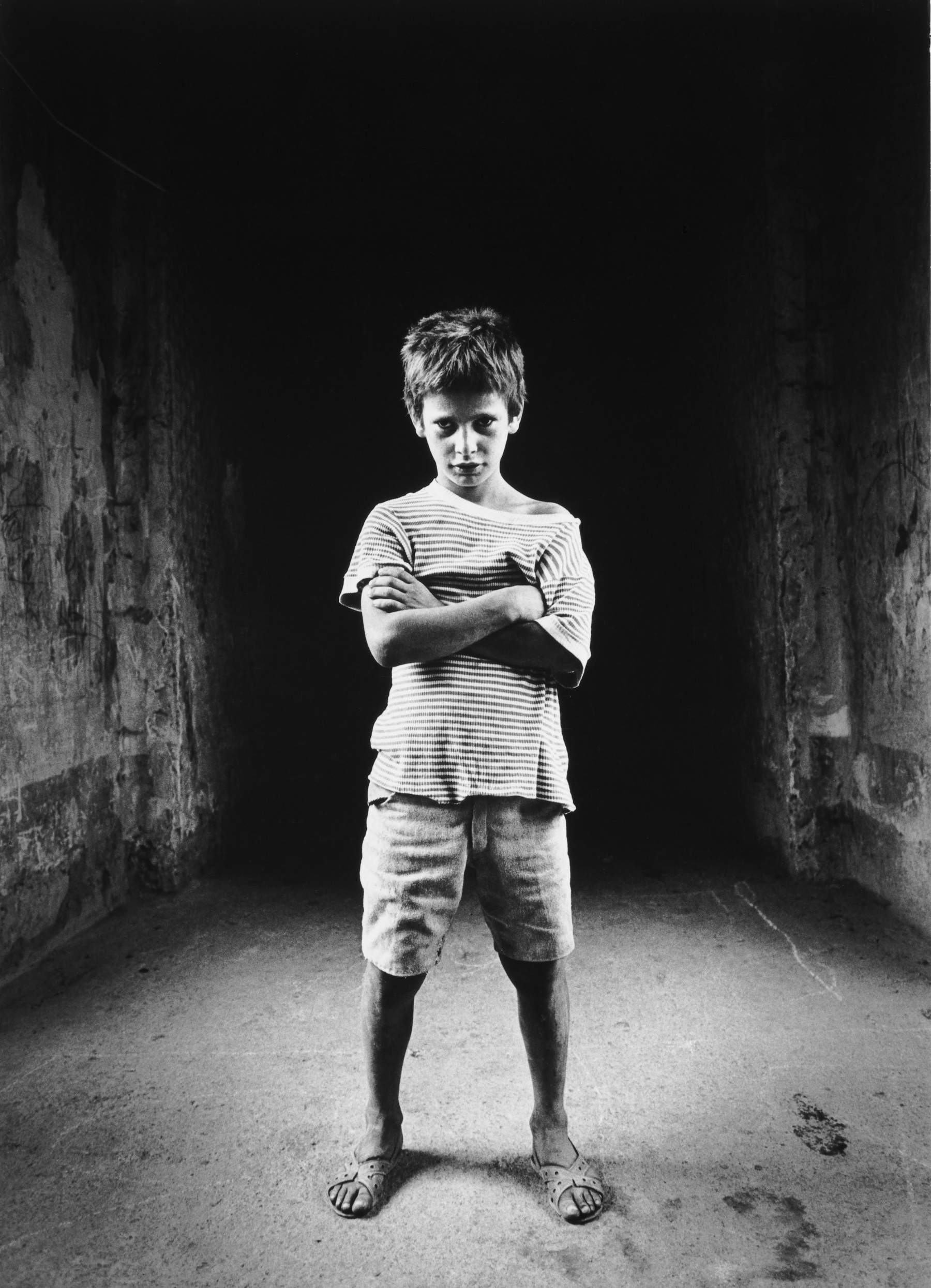

Naples is not only the city where Jodice was born and lived: it is the fabric from which his entire poetics draws sap. “Jodice’s photography,” writes Silvia Bianco, “stems from a process of refined research and creation that is enriched by his personal experiences, by a life lived in Naples, a city he has reinterpreted over the years, the inspiration for many of his visions.” From his earliest photographic series, the Neapolitan city is the protagonist of his shots. With Chi è devoto, Jodice documents the popular religious traditions of the 1970s, restoring a Naples steeped in spirituality and collective rituals. These images are alive, full of emotional participation. But Naples is also pain: in the project I volti del cholera (1972), Jodice recounts an epidemic that profoundly marks the face of the city, recording the human drama with a participatory and intense gaze.

In the following years, however, his vision shifts. With the series Vedute di Napoli (1980), the author abandons the documentary dimension to enter the symbolic one. The city appears empty, timeless, immersed in a rarefied silence. People disappear, and in their place emerge suspended spaces, ghostly architecture, metaphysical atmospheres. Jodice shows us a Naples that no longer exists in real time, but lives in an inner dimension. It is a visual tale of an enigmatic city, far from stereotypes, restored in its cultural and existential depth.

One of the most fascinating features of Jodice’s work is the centrality of absence. Where many photographers look for human presence, action, life in motion, Jodice performs an opposite gesture: he almost completely eliminates man from the scene, but leaves traces of him in space. His urban images, landscapes, empty interiors, are not deserted, but full of silence and memory. Absence, in his pictures, is not emptiness but echo, it is what remains after the passage. It is a dense absence that wants to invite reflection, that questions time and history.

In many series, the protagonist is not what is seen, but what is perceived: the suspension, the waiting, the unspoken. It is a visual language that evokes metaphysical painting, but also the theater of absence dear to the twentieth century. Jodice constructs spaces where the viewer is called upon to fill the voids with his own experience. His photographs are thresholds open to thought. In this sense, photography becomes meditation. Absence is not negation, but a condition for really seeing.

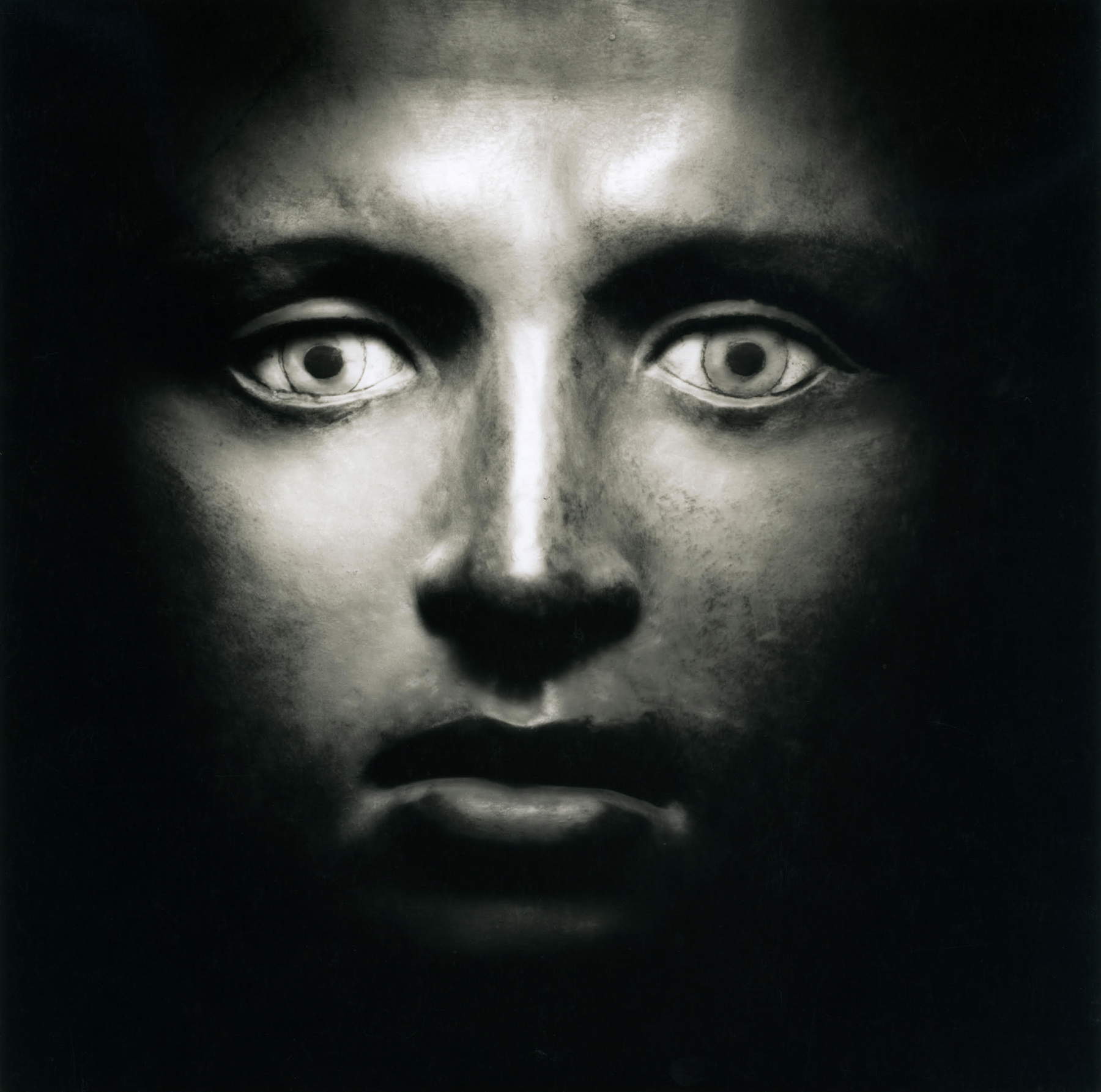

In the 1985-86 project Trouver Trieste, Jodice confronts a city dense with historical stratifications: Trieste. Charged with interpreting it with his gaze, he chose two symbolic places: the Winckelmann Museum and the Risiera di San Sabba. At the museum, among classical statues and ancient vestiges, Jodice enacts a visual reanimation of the past with poetic visions of the past.

At the Risiera, however, the approach is more rigorous, dramatic. A former concentration camp, the Risiera is a place of pain. Jodice approaches it with respect and intensity, photographing its bare architecture, sharp lines, closed spaces. The light here is harsh, vertical, and builds a timeless dimension that invites recollection. In both cases, memory is not just object, but experience. Jodice restores an emotional connection to history, making places speak through composition, light, and silence.

For Mimmo Jodice, the Mediterranean is a place of the soul before it is a geographical space. His Neapolitan roots tie him inextricably to this “mare nostrum,” understood as a cradle of civilization, a theater of collective memories, an eternal setting. His photographic series dedicated to the Mediterranean - in particular The Polyptych of the Villa of the Papyri and The Faces of Memory - explore this universe with visionary eyes. The ancient statues, carved in marble and immortalized by the camera, seem to vibrate with a life of their own.

In Jodice’s images, history is not only represented, but perceived. Classical forms re-emerge in modernity as suspended presences, as relics charged with meaning. His photographs do not seek idealized beauty, but sedimented memory. There is in them a tension toward eternity, an evocation of the permanence of certain human emotions beyond the centuries. The Mediterranean, in this sense, is not background but character: silent witness of wars, myths, art and spirituality. Jodice transforms it into a space outside of time, where the ancient and the modern meet through the universal language of the image.

In Jodice’s most recent works, nature takes on an increasingly central and symbolic role. It is not, however, an idyllic, reassuring nature. On the contrary, the natural landscape - especially one that is mixed with architectural elements or everyday objects - becomes an ambiguous, almost disturbing space. In the “Eden” series, for example, the images pose uneasy questions about our relationship with the environment. Trees are intertwined with artificial structures, ordinary objects are charged with dark, almost threatening meanings.

Nature, in these works, is a stage where the drama of contemporary alienation is played out. The photographer observes how the presence of man-often invisible but perceived-has radically altered the landscape. There is a constant disorientation, a sense of loss. Yet even in this scenario, Jodice manages to capture a poignant beauty, a poetry that emerges from the cracks. Nature thus becomes a place for reflection on our time, loneliness and identity.

After chronicling Naples, Jodice has extended his gaze to other cities-Rome, Venice, Boston, Montreal, Trieste. Wherever he goes, his approach remains consistent: he does not seek tourist representation or didactic narrative, but a form of urban introspection. His cities are spaces traversed by the silent gaze of the author. Architecture becomes symbolic structure; the geometries of buildings, the lines of streets and bridges, the voids between spaces tell of invisible presences.

In particular, Jodice is interested in the relationship between light and architecture. As in a reverse sculptural process, he lets light sculpt the surfaces, reveal the deep identity of the place. His urban photographs are never crowded: they are suspended, metaphysical, almost abstract. In them one senses the melancholy of passing time, but also a tension toward the eternal. Cities become mirrors of interiority, silent theaters of unexpressed emotions.

Jodice’s photography is deeply influenced by the language of painting, particularly the metaphysical painting of Giorgio de Chirico. His compositions reveal an almost manic attention to form, balance, and perspective. The architectural fugues, symmetries, and voids that dominate the scene are all elements that refer to a classical idea of beauty, but also to a sense of mystery. In many of his works, the eye is lost in silent scenes where space seems to stretch to infinity, provoking vertigo and reflection.

Even in the simplest subjects - a statue, a facade, a staircase - Jodice seeks an aesthetic dimension that transcends the contingent. Every detail is chosen, every shadow is intentional. The result is an image that speaks the language of visual art, that dialogues with art history but does so with a new voice.

Mimmo Jodice’s contribution to Italian and international photography is important not only for the aesthetic and poetic quality of his images, but for the way he has been able to transform photography into an instrument of knowledge, meditation, and art. His path teaches that the image should not only show, but make people think; that each shot can contain an entire philosophy.

The main reason for the originality of Jodice’s photography is perhaps his gaze, which can capture the deep meaning of things, which transforms matter into symbol, the everyday into the eternal. For Silvia Bianco, Jodice is “a reference for the new generations for his ability to combine innovation and classical refinement.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.