Those who wanted to make a biopic dedicated to Elisabetta Sirani would have at their disposal all the factors useful for the success of a film: the figure of an independent, cultured woman determined to pursue an extraordinary success, which indeed came; a disturbing love gossip; and a true crime ending with related judicial investigation. Set in mid-17th-century Bologna, the story is entirely real and features a talented painter who knew how to run her own “academy,” who received aristocrats and crowned heads in her atelier eager to admire her skill and purchase her paintings, and who dared to even surpassed the models imposed on Bolognese painters by the great master Guido Reni, elaborating an original language that winked at the novelties of the Roman Baroque. The new volume by Massimo Pulini, a tireless scholar of seventeenth-century Emilia, as well as an artist and professor of painting at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Bologna, traces the biography of Elisabetta Sirani, accompanying it with numerous unpublished works(Il diario di Elisabetta Sirani, NFC edizioni, Rimini, 2025, 288 pages). These, together with the already known corpus, are moreover related to the so-called Diario, a register in which the painter noted the most prestigious commissions and which is reproduced in its manuscript version for the first time.

MS. Who was Elisabetta Sirani, an artist we sometimes hear about and admire a few rare works in research exhibitions, but who is still not as well known as she otherwise deserves to be?

MP. Elisabetta was the daughter of a painter, Giovanni Andrea Sirani, who was already established and active as he held a pedagogical and almost master-builder role within Guido Reni’s workshop. He in fact, as recounted by Carlo Cesare Malvasia, whom we can consider Vasari’s Bolognese counterpart thanks to his collection of biographies of city artists entitled Felsina pittrice, imparted to Reni’s pupils a training based on a rigorous method that involved replicating the master’s inventions. The same approach was probably adopted for the education of the very young first-born daughter, who manifested her talent early on, and Malvasia, a frequent visitor to the Sirani workshop, tells us more about it. It is even said that the girl was “discovered” by the intellectual himself, who persuaded Giovanni Andrea to give her professional training, which, after all, was also the case for two other daughters.

Was Elisabetta Sirani given only training as a painter?

No, we know that she attained a high degree of culture, so much so that the first payment of each year went to the music teacher: Elisabetta was an excellent harp player. We can imagine her as a figure similar to Sofonisba Anguissola, who, however, was of noble birth and was called to the court of Spain in part because of her education as a perfect court maid. John Andrew probably aspired to something similar for his daughters, however, this also entailed a level of intellectual autonomy as a consequence: soon Elizabeth became better than her father.

Despite her father’s and the Bolognese artists’ veneration of Guido Reni, Elisabetta soon departed from tradition, developing a new language, right?

When Guido Reni died in 1642, Elisabetta was only four years old, so she could not meet him in person, however, there were several works by the master in her father’s house, some of them unfinished and destined to be completed by Giovanni Andrea, the only one authorized to do so. From the very earliest works, however, the painter showed that she wanted to be autonomous, and no copies of her from Reni are known; this does not mean that she did not make any, indeed she was probably obliged to by her father, however the teenager (she was in fact about fifteen years old when she began to paint) developed her own independent, spontaneous, and very rapid creativity that made her truly famous. It is known that when she received commissions, Elizabeth would make impression drawings on the idea that would later become the painting. The independence and quality of thought can also be seen in her paintings, in the way she prepared mythological or allegorical subjects.

The desire for autonomy is also confirmed by the affixing of his signature to distinguish his works from those of his father....

In fact, her early successes were followed by a series of slurs that it was her father who had painted some canvases, refined to the point of competing with those of the great Reni. This prompted Elisabetta to sign the paintings, somewhat like Lavinia Fontana had done before her, also in Bologna. Rumors, however, continued to circulate and indeed multiplied when, in her early twenties, she received a commission from the fledgling church of San Girolamo alla Certosa for the gigantic canvas with the Baptism of Jesus. The commission was among the most coveted by Bolognese painters, and the artist not only held his own against the prestigious commission, but also managed to handle a crowd of characters, creating a very complex sacred scene. He then affixed his signature to it in large letters.

Can it be said that Bologna was a very competitive city in the artistic field, and that this atmosphere deeply marked Elisabetta Sirani’s life and death?

Bologna was at the time the city with the highest concentration of painters in relation to its inhabitants. More than Rome, Naples, Genoa: this was because not only native artists stayed there, but also many from outside, and this was already for several decades. The Carracci Academy first, and then the workshops of Reni and Guercino, were real industries. Such a “crowd” made the environment extremely competitive, and under Bologna’s porticoes malicious rumors ran fast. Moreover, the city was very attached to its artistic tradition, which rightly made it one of the European capitals of painting, but at the same time this entailed a certain closed-mindedness, a self-sufficiency that Giovanni Andrea Sirani himself manifested. The airiness, the fresh and open, happy and joyful quality of Elisabetta’s works (while remaining in the groove of the Bolognese tradition) thus presented themselves as novelties. Especially in the later paintings one perceives a moved brushstroke in the drapery and expressions of the figures that looks to Rome, to Carlo Maratta, and to Giovan Battista Gaulli, although we do not know how she came to know the Roman Baroque. Perhaps through paintings, drawings and engravings that reached Bologna, he also visited the court of Modena where he admired Velázquez; and it is not excluded that he may have traveled to Central Italy with his father.

Despite her desire to go to study in Florence or Rome, her father kept her in his workshop and prevented her from leaving. Why?

After receiving the title of academician from the Accademia di San Luca, hopes were kindled for Elisabetta to go to study in Florence or Rome, but her father, however, refused to let her travel alone, partly because he was having health problems at the time and Elisabetta’s workshop help had become crucial for business. It was the daughter, in fact, who carried the family forward financially, partly because her canvases cost much more than Giovanni Andrea’s. At that point she responded to her father with a historic phrase: “If I can’t leave Bologna, I’d rather not even leave home. But I want my school here.” An all-female school.

Is this school for women painters unique in the Italian scenario of the seventeenth century?

Yes, Elisabetta called her school “Accademia” and managed to involve up to 15 female pupils at the same time among noble and married women from Bologna who took the opportunity to attend both Sirani’s and Ginevra Cantofoli’s classes; the latter was twenty years older than Elisabetta and had herself been a pupil of Giovanni Andrea. The women’s academy was the first and only one for a long time, but after Elisabetta’s death it was unfortunately inevitably dismantled. Some of the women painters sought work in other workshops, but although women artists were publicly and officially considered in Bologna, there were still those who rejected them.

In your very recent monograph you reconstruct the corpus of Elisabetta Sirani, also publishing many unpublished works. How much did this painter draw and paint?

In 30 years of research I managed to track down 55 unpublished drawings, engravings and paintings, and the trigger for publishing this book was the discovery in Montefiascone of the 15 tablets with the Mysteries of the Rosary. In total, Elisabetta’s corpus currently numbers nearly 400 pieces-a substantial amount when one considers that she worked just over ten years.

In the book, the works are also contextualized in the “grid” of the artist’s Diary. Besides being an invaluable source for reconstructing the artist’s career, why is this manuscript so important?

Elisabetta began compiling this register in 1655 and updated it until 1665, until shortly before her death, and the first work mentioned is an altarpiece she made for the Marquise Spada. Certainly this is not his first work ever, which says a lot about the fact that he had already demonstrated his talent. Notably, Sirani notes in the manuscript the commissions, then only the works she is asked to do, and indicates both the theme and the name and surname of the person for whom the work is intended. She also notes the visits of high-ranking people who visit her: for example, Duchess Enrichetta of Savoy came to her atelier, and the painter produced a cupid before her. Many rulers and nobles who passed through Bologna did not fail to go and observe the work of this woman painter in person, thus becoming the witnesses of her skills. On the other hand, the Diary does not mention, but they are equally autographed, many other works-also signed and dated-that Sirani produced on her own initiative.

What other curiosities emerged from the analysis of the Diary?

One curious aspect is that Elisabetta Sirani became sought after for her ability to make postmortem portraits. It all began with an initial portrait of her inquisitor father Guglielmo Fochi, which was greatly appreciated as something life-giving, capable of bringing the character back to life. Word then spread, and when a gentleman or aristocrat of whom no recent portrait was owned died, Elizabeth was summoned, and during the wake she made sketches in drawings such as those preserved at the Royal Collection Trust in London. Also probably made post mortem is the effigy of a child holding a bouquet of flowers, as the cut flower is a symbol of death. It is striking to imagine this little girl painter climbing up on a chair during rosary recitations to observe the face of the corpse from the right perspective, bringing back her likeness in the notebook: it is a very cinematic scene.

Let’s move from the theme of death to love-what gossip do you speculate on the basis of written sources?

We have already mentioned the interest of Malvasia, who was a canon, in Elizabeth’s talent, but it is surprising to read carefully the biography he writes for Felsina the painter. In addition to a long proem that is very rhetorical, the author adopts a totally different phrasing than in the other lives, to the point that Luigi Crespi, when rewriting Felsina a hundred years later, claims that the canon seemed dulled by grief. I think, therefore, that Malvasia was genuinely in love with the young Elisabetta, so much so that at one point the canon switches from the third person to the second person, calling the subject "tu. He even hints at a future reunion and, a few years after her death and despite evidence of a natural death, hurls anathemas at those he believes to be guilty of poisoning Sirani. Finally, we know that he had commissioned from Elisabeth allegories of virtues and moral concepts that seem almost like allegorical self-portraits. It is only a hypothesis, but everything points to an amorous thought of Malvasia, perhaps simply chaste-and whether reciprocated is unknown.

We close this interview with the grand tragic finale, Elizabeth’s death. How did her life pass away at only 27 years of age?

The artist, after a few weeks spent enduring very acute pain, died of a chronic, perforated ulcer, which was certified by a second autopsy, following the one performed by the attending physician, who had assumed poisoning. The sudden death, in fact, had thrown the father into despondency and, inconsolable, he accused a servant girl of poisoning his daughter. It must be kept in mind that the aforementioned feelings of envy on the part of many artists who had failed to achieve as much success as Elizabeth’s were still alive. Malvasia nevertheless continued to believe in the hypothesis of murder by poison, as we have already mentioned, “although this is not properly Christian,” he writes. Inevitable then to ask the question: if Elisabetta Sirani had lived longer, today she would perhaps surpass the archly famous Artemisia Gentileschi in fame and certainly would have contributed to spreading a breath of modernity in second-century Bologna.

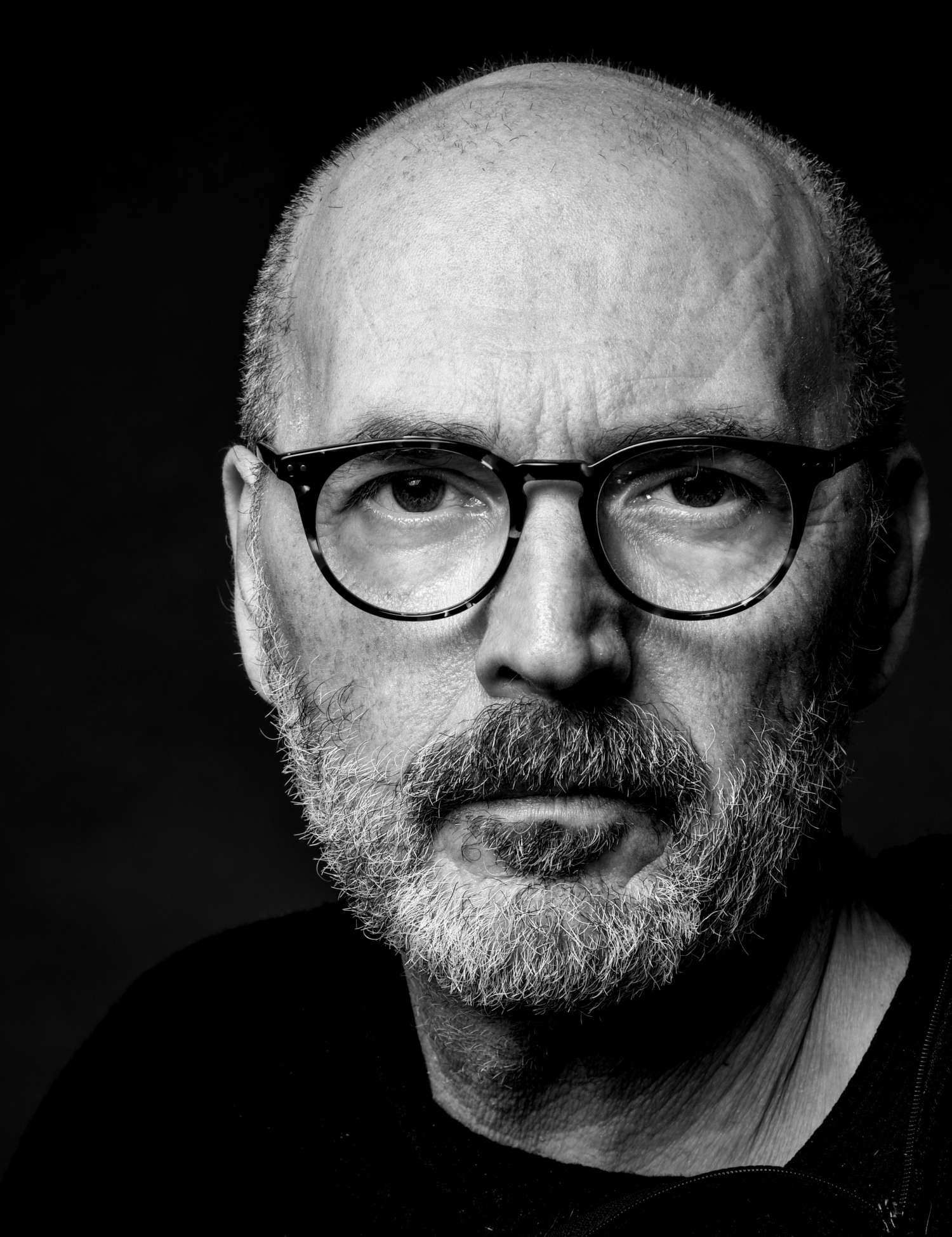

The author of this article: Marta Santacatterina

Marta Santacatterina (Schio, 1974, vive e lavora a Parma) ha conseguito nel 2007 il Dottorato di ricerca in Storia dell’Arte, con indirizzo medievale, all’Università di Parma. È iscritta all’Ordine dei giornalisti dal 2016 e attualmente collabora con diverse riviste specializzate in arte e cultura, privilegiando le epoche antica e moderna. Ha svolto e svolge ancora incarichi di coordinamento per diversi magazine e si occupa inoltre di approfondimenti e inchieste relativi alle tematiche del food e della sostenibilità.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.