There is a moment, when the late afternoon light hits a pastry shop window, when everything seems suspended. The shadows lengthen, the colors saturate, and each frosting reflects a golden glimmer. It is in this precise instant that Wayne Thiebaud (Mesa, 1920 - Sacramento, 2001), a painter who made sweetness a matter of gravitas, lives.

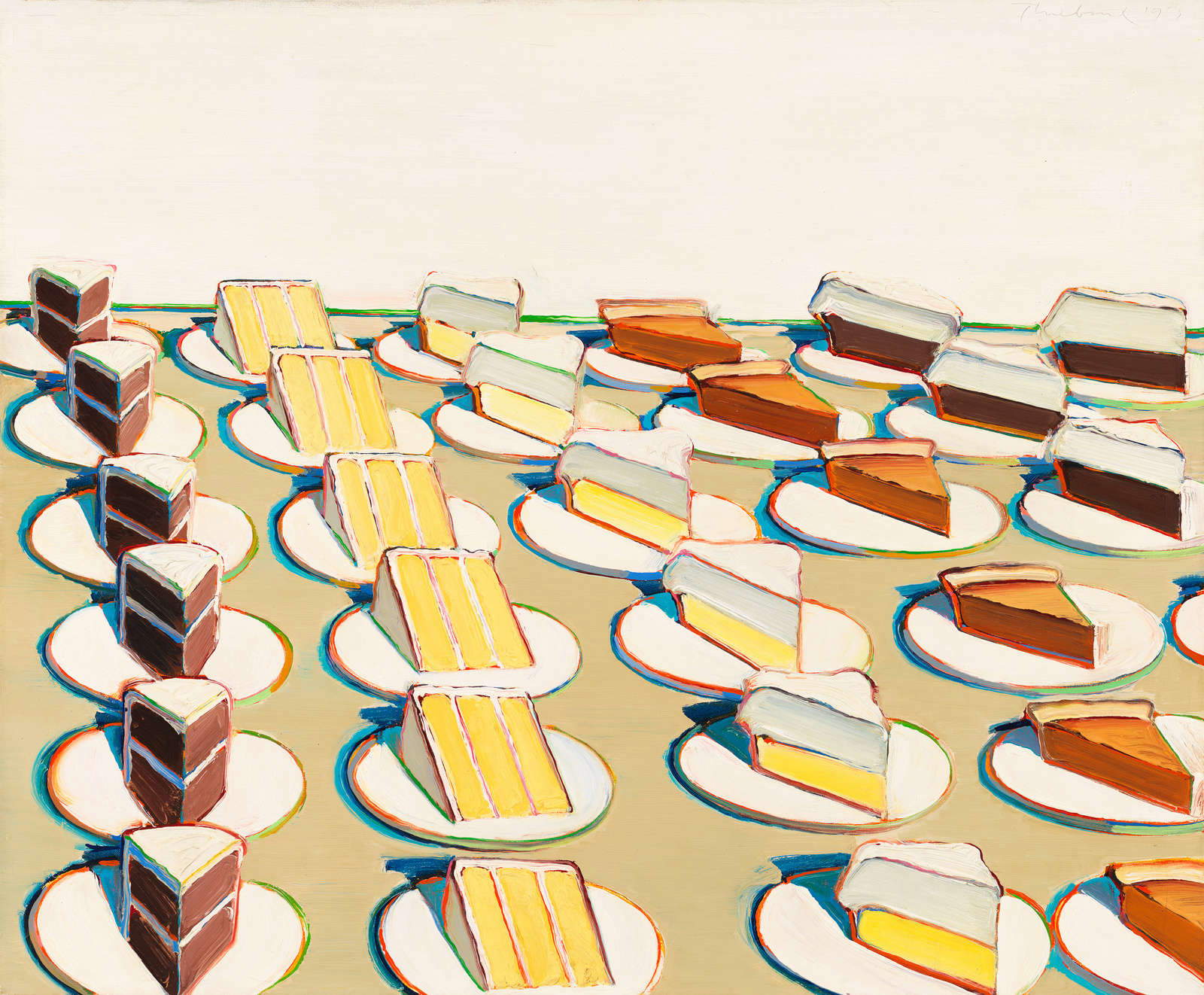

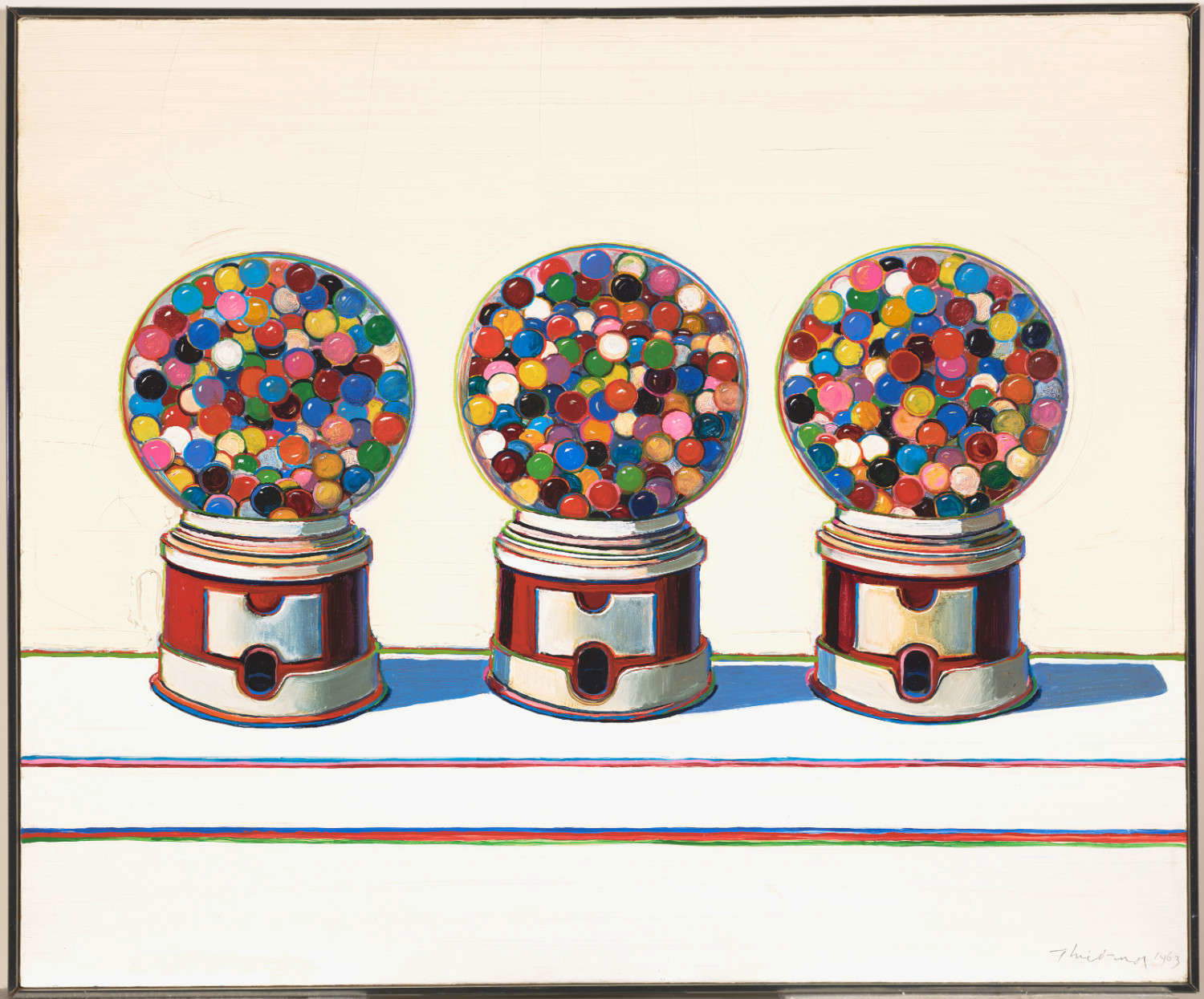

Thiebaud was never just the artist of cakes and candy. His sugary America is a subtle trap: it looks inviting, familiar, but carries a melancholy weight. His sweets, isolated on monochromatic backgrounds or repeated in perfect rows, are icons of an abundance that, on closer inspection, never really satiates. The dense, textural pastel, lifting creams like butter hills, is not mere decoration: it is a statement of presence. The material kneads with memory.

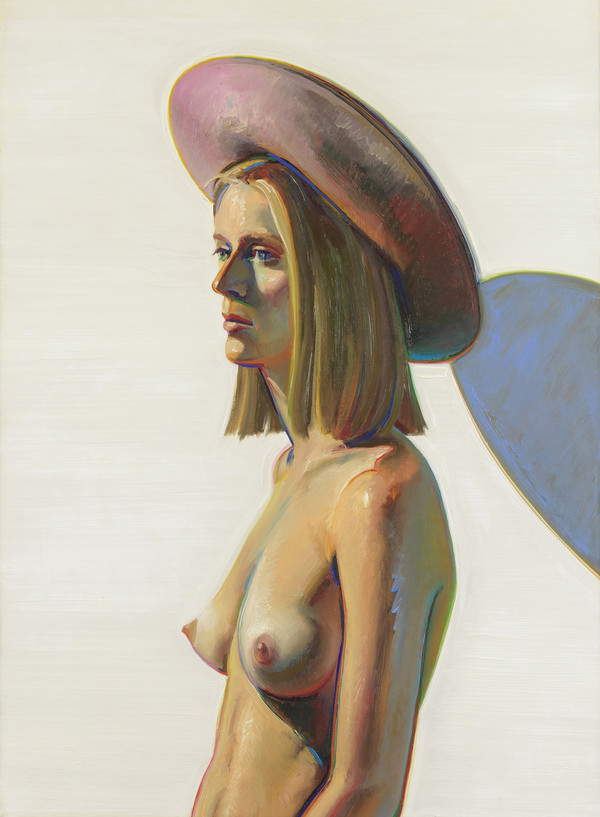

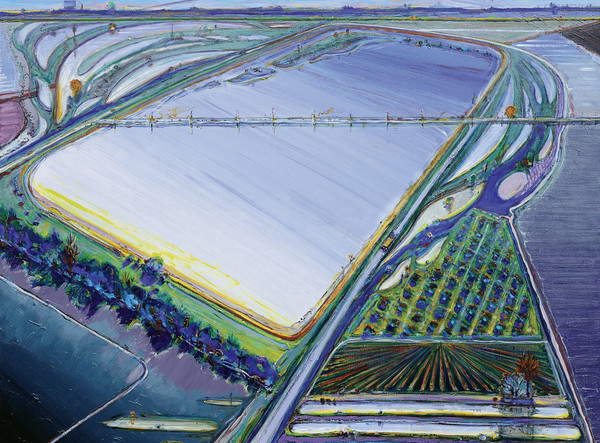

Thiebaud’s training, somewhere between advertising and the painting tradition, allowed him to sharpen his gaze. He was not a pop artist in the canonical sense, although he has often been associated with the movement because of his interest in the products of mass culture. But the difference is substantial: while Warhol reproduced Campbell’s Soup to empty them of meaning, Thiebaud painted his storefronts with an almost religious sense. There was no irony, no alienation, but a dense, almost painful nostalgia. His cityscapes, with streets soaring vertically like impossible mountains, reveal another side of his vision: his America is a place of vertigo and desire, of consumption and loneliness. Every element is calibrated with the precision of an architect, yet the feeling is always one of precariousness, of a balance that could break at any moment.

Finally, there is a detail that few notice in his works: the use of a cool blue shadow along the outlines. An imperceptible detail, but a decisive one. That blue line is the boundary between sweetness and regret, between beauty and illusion. Looking at a Thiebaud painting is like tasting a dessert from childhood: the taste comes immediately, enveloping. Then, an instant later, it dissolves. And it is precisely in that instant that we realize how heavy the sugar is.

But who was Wayne Thiebaud really? Born in 1920 in Mesa, Arizona, he spent much of his childhood in California, a state that would become his main source of inspiration. His artistic journey began in the world of advertising graphics and animation, profoundly influencing his painting style. He also worked as an illustrator for the Walt Disney Company before embarking on an academic career, teaching art at the University of California.

His distinctive style was the result of constant research into the use of color and light. Thiebaud exploited traditional techniques with an almost impressionistic approach, juxtaposing complementary colors to create depth and volume. His blue and purple shadows, so unusual compared to the canonical gray range, gave his subjects a strange three-dimensionality, as if they were floating in a world suspended between reality and dream.

Another fundamental aspect of his work is the concept of repetition. The neat rows of cakes, donuts and lollipops are not only an echo of mass production, but also a way of exploring seriality in art, a theme dear to many twentieth-century artists. However, where pop artists used repetition to critique consumerism, Thiebaud employed it to create a sense of order, as if each object had its own precise place in the world.

Some of his most famous paintings, such as Cakes (1963), Pie Counter (1963) and Three Machines (1963), show this ability of his to elevate everyday objects into true visual icons. In Cakes, a series of colorful cakes is arranged on a countertop in a geometrically perfect manner, evoking a certain staticity that contrasts with the softness of the subject. Pie Counter, on the other hand, suggests an almost hypnotic repetition, where each slice of pie seems to be part of a ritual of desire and abundance. Three Machines, with its bubble gum vending machines, captures a suspended moment in American culture, where the banality of the object is transformed into something symbolic and almost metaphysical.

Throughout his career, Thiebaud received numerous awards, and his works entered the collections of the world’s most important museums, including MoMA in New York and the National Gallery of Art in Washington. Despite his fame, he always remained connected to his dimension as a teacher and mentor, influencing generations of artists with his meticulous and passionate approach to painting.

In the end, Wayne Thiebaud was not just the painter of sweet things. He was the silent guardian of anAmerica suspended between longing and nostalgia, a craftsman of light who could make simple things shine with a poignant intensity. His works are open windows on a world that always seems one step away from dissolving, as sweet as a memory, as fragile as a reflection on icing.

Even today, each of her cakes, each of her steep roads, whispers to us the elusive taste of time, reminding us that beauty, like sugar, is destined to melt, leaving behind the subtle taste of absence.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.