Aligi Sassu (Milan, 1912 - Pollença, 2000), among the major artists of the second half of the twentieth century in Italy, made color his unmistakable signature, using it to bring to the canvas a personal point of view on reality and the world that is open, sensitive to civil commitment, cosmopolitan, interweaving stories and figures from the past, mythological, with those more contemporary and current to him.

Well known are his works with horses as protagonists, animals that he favored: however, Sassu is often juxtaposed only to this symbol, while his production turns out to be much more extensive and includes different themes that he brought to series, such as the famous Red Men and paintings with a religious theme in which he uses the scenes of the Crucifixion and the Deposition of Jesus as an expedient to launch messages of civil denunciation. Sassu was, in fact, convinced that the artist should have a social function. Over the years, in addition to painting and drawing, Sassu ventured into large-scale masonry works that are publicly visible in several Italian cities.

Aligi Sassu was born in Milan on July 17, 1912, from the union of Lina Pedretti, originally from Parma, and Antonio Sassu, of Sardinian descent. His father had moved to Milan in 1896 after being one of the founders of the Italian Socialist Party in Sassari, and in the Lombard capital he formed a close friendship with the futurist Carlo Carrà. From an early age, Sassu thus came into contact with the Milanese avant-garde. The family returned again to Sardinia when Sassu was about nine years old, and the time spent in his home region exerted a great influence on the artist, especially for its colors and characteristic landscape views. Meanwhile, upon returning to Milan, Sassu began working to make up for the economic hardship caused by the persecution of his father for his anti-fascist views. Among his various jobs was as a masonry decorator, which impracticed him in painting techniques while he tried to take evening courses at theBrera Academy. He became very interested in Futurism and befriended the Futurist designer Bruno Munari, together with whom he went to meet the movement’s founder Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, who summoned the young Milanese artists to meet them in person. Following the meeting, Marinetti invited Sassu to participate in the 1928 Venice Biennale. In the same year, Sassu and Munari signed the manifesto “Dynamism and Muscular Reform,” with the aim of regulating the representation of anti-naturalistic forms in a dynamic way. The manifesto remained unpublished until 1977.

Sassu officially entered the Brera Academy and met, among other students, Lucio Fontana. However, he had to leave the academy after two years because the costs were too high, so he took up theAccademia Libera, which allowed young artists with low budgets to use a variety of tools in exchange for a commitment to make one painting a month. After the Accademia Libera closed, between 1929 and 1932 Sassu rented a studio together with Giacomo Manzù, and began participating in several group exhibitions, where he became the object of critical interest. In 1934 he moved to Paris, studying the great masterpieces preserved in the museums of the French capital, being particularly impressed by the Impressionists and Delacroix. Here he got to know Filippo de Pisis, Lionello Venturi and Fernand Léger, thanks to whom he was able to exhibit some works at the Galerie des Quatre Chemins.

The following year he began to be politically active, strong in his conviction that artists had a moral duty to fulfill a specific social function. After returning to Milan he militated as an anti-fascist and anti-Francoist, forming the Gruppo Rosso together with several other artists including Renato Guttuso. Together with the group, Sassu organized several demonstrations of disturbance and protest and disseminated leaflets bearing anti-fascist phrases, being arrested and imprisoned first for six months at San Vittore and later at Regina Coeli in Rome with a ten-year sentence. He was then transferred to Fossano Prison, and here the jailers allowed him to draw; finally, he was released in 1938 thanks to Marinetti’s intercession, but he was forbidden to exhibit his works.

At the conclusion of World War II, Sassu moved to Castel Cabiaglio, in the province of Varese, to start an artisanal ceramics business by restoring an old kiln. However, the experience did not last long, but continued for a period in Albissola, where he was a guest of ceramist Tullio Mazzotti. Together with Mazzotti he met Pablo Picasso in 1954, and he also met the Colombian singer Helenita Olivares, to whom he married on his second marriage (he had previously married and had a daughter, but divorced a few years later). In 1964 he moved to Spain, buying a house in Majorca, devoting himself among other things to raising horses, his favorite animals that he often represented in his works. He returned to Milan only in 1981, the year in which he received the award “The men who made Milan great.” He was also given other awards, in fact in 1965 he was appointed a member of UNESCO’s Italian committee for plastic arts, and in 1994 he was made a Knight of the Grand Cross by the president of the Republic.

He decided to donate numerous works created from 1927 to 1996 to the city of Lugano, establishing the Aligi Sassu and Helenita Olivares Foundation, which organized several major exhibitions dedicated to the artist around the world. Sassu died on July 17, 2000, his birthday, at his home in Pollença, Majorca. The Foundation continued its commitment to bring his works on display even after his death. Inontre. in 2005 he was awarded posthumously by President of the Republic Carlo Azeglio Ciampi the gold medal for merits in the promotion and dissemination of education, culture, art and research.

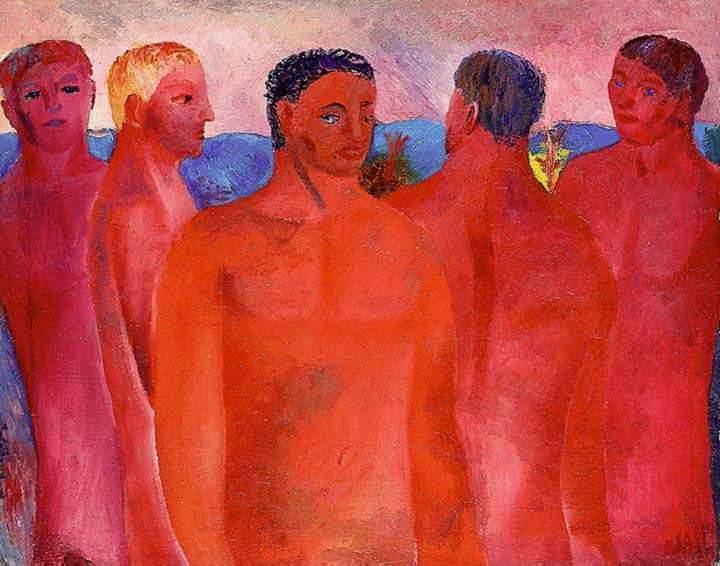

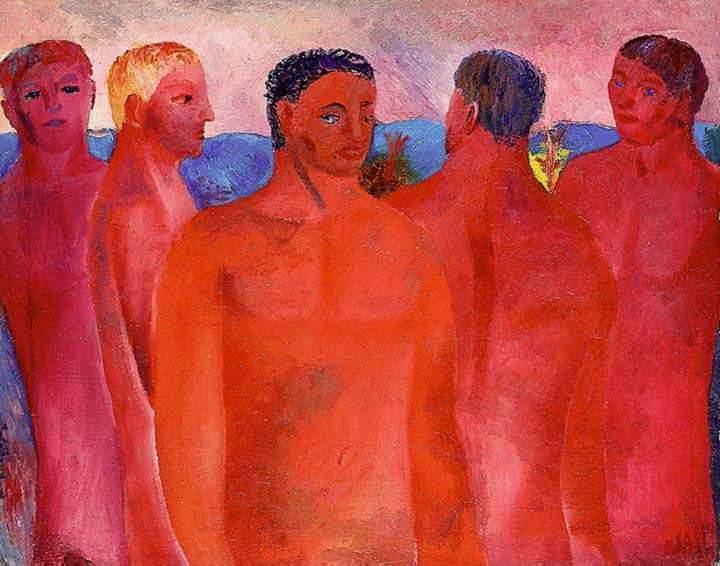

Sassu’s youthful model of inspiration was the Futurist Umberto Boccioni, especially for the way he was able to render solid form in the pursuit of dynamism. After all, the influence of Futurism is clearly present in Sassu’s beginnings as a painter, between 1927 and 1929, as his paintings focused on themes that were contemporary to him, dynamic and modern, such as sports, industries and machines. He mainly produced series of works with the same subject, the most famous of which include The Cyclists, which stemmed from his direct experience as an amateur cyclist with his brother. He devoted himself starting in 1930 for three years to the Red Men series, which consisted of more than five hundred works, depicting a wide variety of figures, from mythological ones such as the dioscuri and argonauts to more commoners such as dice players, shepherds, players and many others, engaged in playful activities and pastimes as if they were in a “magical” world other than reality. The predominant color in this series is, as the title itself suggests, red. A choice that was the subject of attention by critics in the 1930s for its innovative contribution. Sassu was indeed an assiduous frequenter of the Futurist milieu, however, already as can be seen from his youthful works, he preferred to take more personal paths and in antithesis to his contemporaries, studying in depth the masterpieces of Masolino and Beato Angelico, for that matter traveling to Florence by bicycle with the intention of admiring them up close. He approached, moreover, the current of Primitivism.

Late 19th-century painting was also among his favorites, and among the painters who most inspired him Sassu pointed to Paul Cézanne, the Impressionists, and especially Eugene Delacroix.

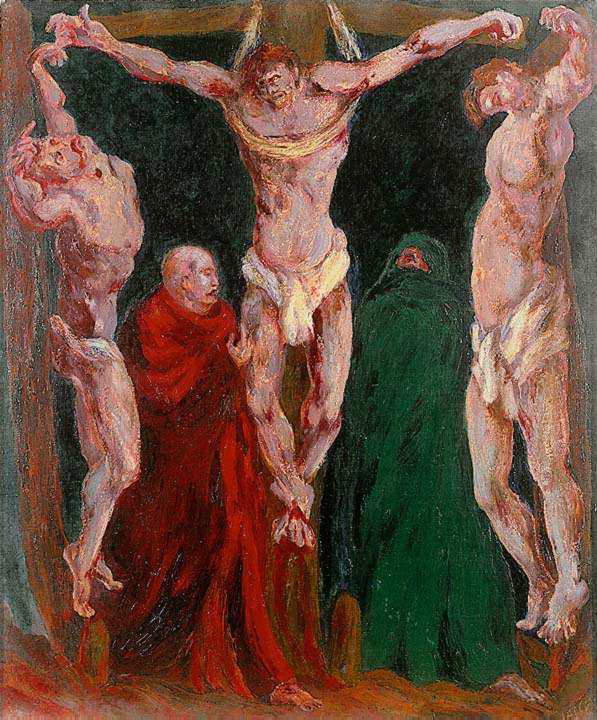

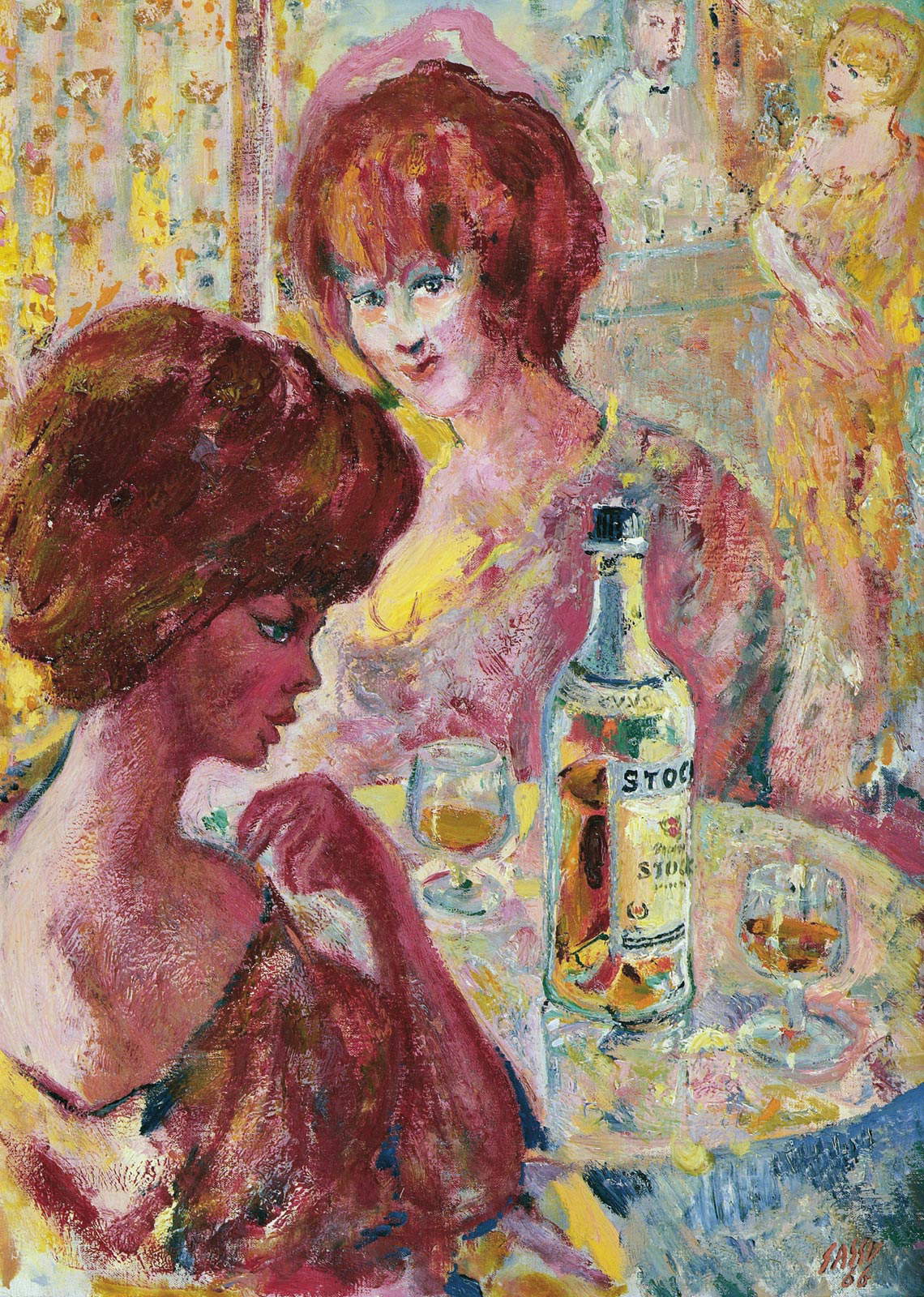

An important part of his painting also consisted of sacred works, a genre that particularly fascinated the artist because of the great narratives, characters, and symbols that recur in the Catholic religion. Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi, in this regard, declared, “What won him over above all was the Crucifixion, a sign that he considered capital for his faith, but also for his art and for the very history of humanity.” Other series from the 1930s are Argonauts and Cafes, inspired by frequenting Milanese cafes in which red-haired women often recur, depicted with a mixture of eros and melancholy. Also, from his frequentation with boxer Cleto Locatelli came the series of paintings and drawings of the Pugilatori (Boxers).

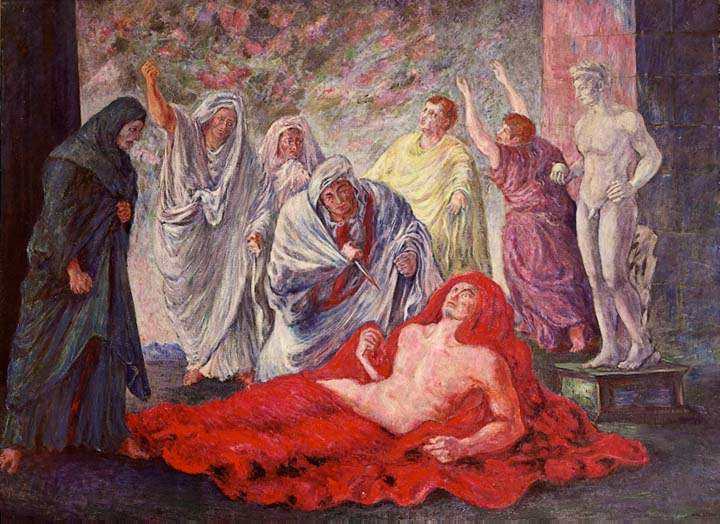

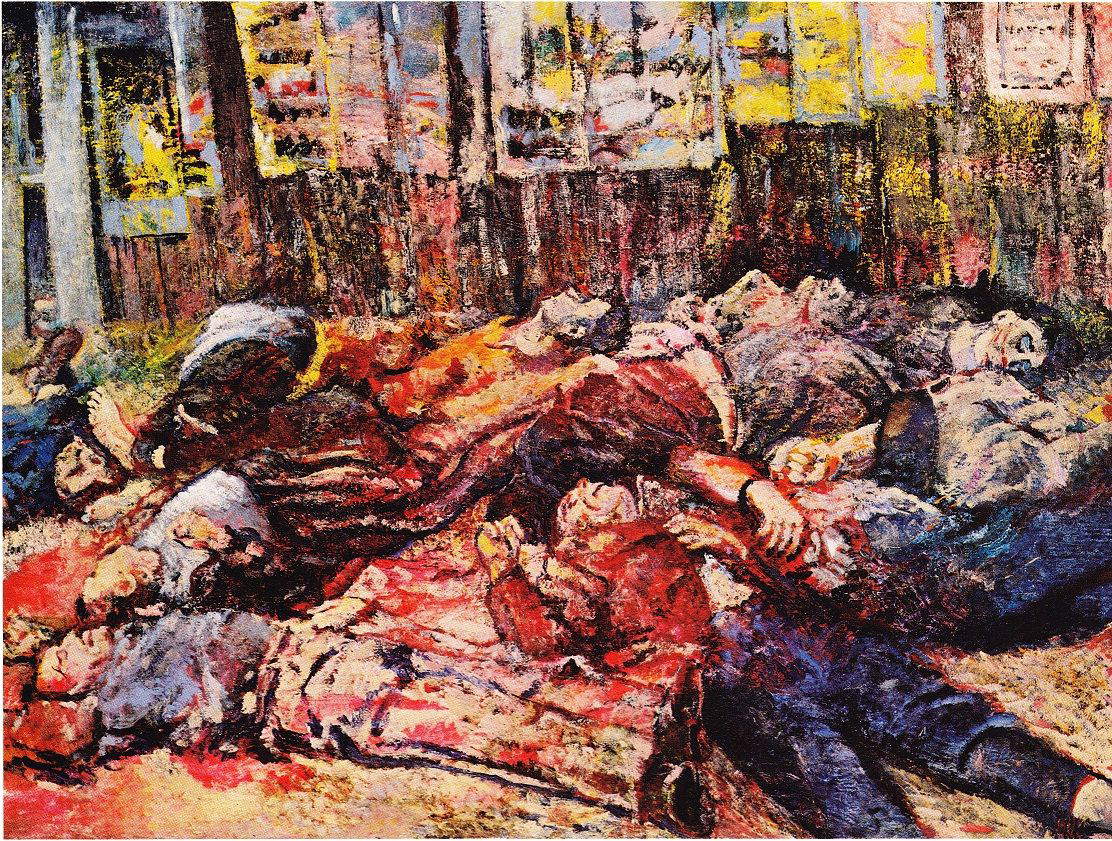

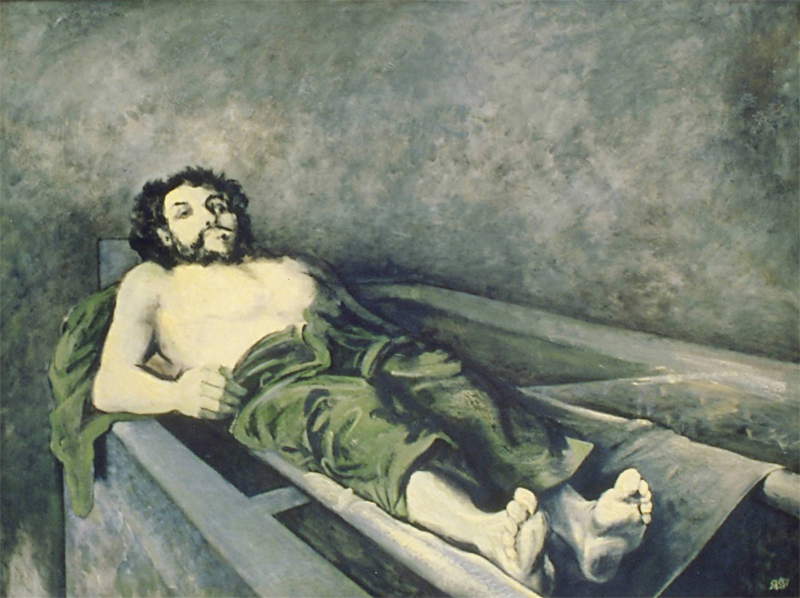

In the Fossano prison, Sassu made more than four hundred drawings depicting other inmates or reproducing mythological themes. After his release from prison, however, he continued to paint mainly opposition works, including Spain (1937), and The Death of Caesar (1938-39), which he had begun to conceive while in prison and which reflected his growing interest in social themes. In 1942 he continued making paintings with religious themes, inaugurating the Councils series, including The Council of Trent . He also painted a Deposition in which he combined together the religious episode with a denunciation of social injustices. He was greatly affected by the episode in which a group of partisans and anti-fascists were shot in Piazza Loreto in Milan, and he decided to vent his upset in a work entitled I martiri di Piazzale Loreto (1944), which he completed in two days.

Sassu’s experience in Albissola led him to master the technique of ceramics, in which he brought back his pictorial signature. He made artifacts featuring horses, horsemen, or the scenes in cafes. He experimented with new techniques of using glazes to enhance the color on the material.

During his time in Albissola he painted another cycle entitled Chronicles of Albissola, bringing to the canvas the thriving artistic life of the town, where potters, poets, writers, critics, and artists in general gathered. In the very Piazza del Popolo where they used to meet, the work The Horses of the Sun was placed. Also, in collaboration with others such as Lucio Fontana and Giuseppe Capogossi he created the Passegiata degli artisti consisting of glassy paste tiles over seven hundred meters long, which was inaugurated in 1963.

During his time in Spain Sassu painted bulls , bullfighters and local landscapes, seeking out and experimenting with new techniques, such as acrylic, which allowed him to render the vivid colors of Majorca in a more pointed manner. The Tauromachie series was born in this period. In 1968 he made large paintings, including Che Guevara . Three years later he made two large mosaics for the church of Sant’Andrea in Pescara. Upon his final return to Milan in the 1980s, he began collaborating with publishing houses on illustrations for literary masterpieces such as the watercolors he made for The Betrothed. Sassu’s activity as an illustrator had been quite frequent over the years; in fact, he had already produced a series of lithographs and illustrations in the immediate postwar period. He had also painted a cycle inspired by Guy de Maupassant’s novella Maison Tellier, in which he combined contact with literature with social denunciations on the subject of prostitution.

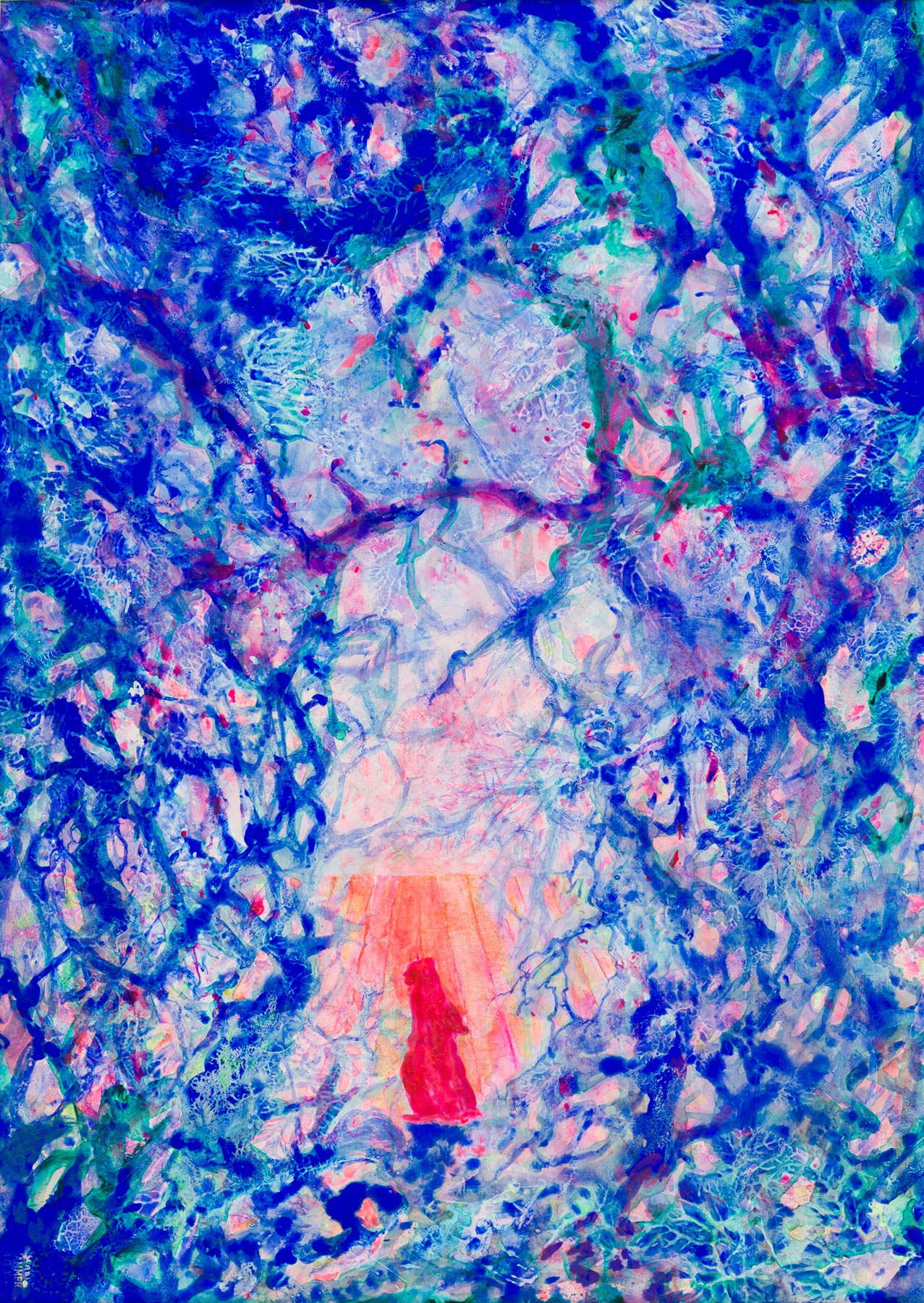

He also illustrated as many as 113 plates for the Divine Comedy, which were first exhibited in 1987 at the “Sassu and Dante” exhibition at Castello Gizzi in Torre de’ Passeri (Pescara). It was to all intents and purposes a reworking of Dante’s text in a different artistic language, much influenced by the subjectivity of the artist. For Sassu it was a fairly spontaneous operation, as he found in Dante’s work a parallelism with his artistic expressiveness and a way to reflect on his art. The bodies and figures consist of pure color, and fundamental is the use of light.

Very famous was a large-scale mural, as many as 150 meters, from the series The Myths of the Mediterranean, created for the new headquarters of the European Parliament in Brussels in 1993, made of ceramic.

Sassu’s activity in monumental public art had already begun in the 1950s, with the fresco La miniera (1950) specially conceived in Sardinia in the mines of Monteponi, near Iglesias, to represent the theme of work through mythical figures placed in an industrial landscape. He then continued with a series of frescoes and mosaics for various buildings throughout Italy.

In the Sardinian town of Thiesi, a museum dedicated to the artist has been established by the Aligi Sassu and Helenita Olivares Foundation, in which 120 works created by the artist between 1929 and 1995 are collected, mainly etchings, aquatints and lithographs. Also preserved inside is the large mural I moti angioini (1962), which was originally executed for the exterior walls of the Thiesi Elementary School but was deteriorating.

Numerous series works by Sassu are found in the Aligi Sassu and Helenita Olivares Foundation in the city of Lugano. In addition, the Aligi Sassu Museum was opened in the Abruzzi town of Atessa in 2010, where hundreds of works including drawings, paintings, lithographs, ceramics and sculptures are on display, covering all phases of Sassu’s artistic production, from Cyclists to Red Men, from Crucifixions to Cafes and many others.

The work The Martyrs of Piazzale Loreto (1944), was purchased by Giulio Carlo Argan for the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art, where it still stands today. Finally, the public mural works signed by Sassu are worth mentioning: Myth of Prometheus (1954), executed in his house in Albissola, and now in the palace of the Province of Sassari, and the two mosaics executed in the church of Sant’Andrea in Pescara in 1971, the fresco Myth of the Mediterranean (1993) in Brussels in the European Parliament building.

|

| Aligi Sassu, great artist of the 20th century. Life, style, works |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.