Giambattista Tiepolo (Venice, 1696 - Madrid, 1770) was probably the greatest Rococo artist in 18th-century Italy. A Venetian who was open to all the suggestions he received (from the tenebrism of Giovanni Battista Piazzetta and Federico Bencovich to the luminous atmospheres of Ludovico Dorigny), Giambattista Tiepolo matured a clear and airy style in which the significance of the achievements of Baroque painting was distorted: perspective illusionism, with Giambattista Tiepolo, is no longer a means of engaging the viewer and making him a participant in a vision, but is a means of creating a fictitious and almost abstract reality in a society in the midst of decadence such as that of 19th-century Venice. A highly theatrical art in which the characters are no longer realistic, but seem almost like actors in a play, for a style that Tiepolo from Venice later spread throughout Europe, from Würzburg to Madrid.

Venice, in the eighteenth century, became an important artistic hub because not only was a large part of the art market of the time concentrated here, but also because attracted by the beauty of the landscape and the history of these lands artists from all parts of Europe came to Venice, thus giving rise to fruitful and productive cultural exchanges that made Venice a center of international importance, and Venice itself then spread its own way of seeing and producing art throughout Europe. In Venice, at the beginning of the century, a luminous and terse late Baroque style of painting spread, drawing its origins from 16th-century painting, particularly the art of Paolo Veronese, and then enriched by the experiences of artists such as the Carraccis and Luca Giordano: leading exponents of this trend were Sebastiano Ricci and Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini, who were also among the Venetian artists able to spread their way of making art in Europe, as both stayed in England and Pellegrini also moved for some time to Paris, Düsseldorf and Vienna. The experiences of these artists were the basis for the birth of Rococo painting. The opposite current, on the other hand, was that of tenebrism, which saw its greatest exponent in Giovan Battista Piazzetta and which originated from the painting of Giuseppe Crespi.

Tiepolo soon began his apprenticeship with Gregorio Lazzarini, a Venetian painter very much in vogue in the second decade of the eighteenth century, an artist with a classicist bent: Tiepolo entered his workshop in 1710. In the first phase of his career, the artist also shows that he was influenced by Giovanni Battista Piazzetta and Federico Bencovich, another tenebrist painter like Piazzetta: however, Giambattista Tiepolo would always demonstrate a great eclecticism, capable of leading him to quickly absorb all the suggestions he received in order to elaborate his own style. This peculiarity of his is particularly evident in his youthful production because then later in time his style would evolve in a precise direction.

|

| Giambattista Tiepolo, Apotheosis of the Pisani family (1761-1762; fresco, 2350 x 1350 cm; Stra, Villa Pisani) |

Giambattista Tiepolo was born on March 5, 1696, to Domenico, a small shipowner, and Orsetta Marangon, in a wealthy family but of no artistic tradition. In 1770 the artist was already reported to be active in Gregorio Lazzarini’s workshop. Also important to his training would be such tenebrists as Giovanni Battista Piazzetta and Federico Bencovich. In 1715 he worked on one of his very first works, the soprarchi of the Ospedaletto church in Venice, with figures of five apostles and the sacrifice of Isaac. Giambattista first appears in the Fraglia of Venetian painters in 1707. In 1719 he began work on frescoes in Giovanni Battista Baglioni’s villa in Massanzago, between Venice and Padua: they would be finished the following year. For the first time Giambattista enlisted the help of Girolamo Mengozzi known as il Colonna, a quadraturista (i.e., painter assigned to the creation of painted architectural wings) who would accompany the painter for almost his entire career. In the same year he married Cecilia Guardi, sister of the great Vedutist painter Francesco Guardi. From Cecilia, Giambattista would have nine children.

In 1721 the church of Sant’Aponal commissioned him to paint the Madonna del Carmelo, completed in 1727 and now in the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan. The following year, the artist painted the Martyrdom of St. Bartholomew for the church of San Stae in Venice: it is one of his greatest masterpieces. In 1724, Tiepolo executed the fresco decoration of the chapel of St. Theresa in the Church of the Scalzi in Venice, completed the following year. The Patriarch of Aquileia, Dionisio Dolfin, commissioned him in 1726 to paint frescoes for the Patriarchal (or Bishop’s) Palace in Udine, the artist’s masterpiece, which would be completed in 1729. In 1727 his son Giandomenico was born, who was to become an artist of considerable depth. Giambattista later moved to Milan in 1731, where he stayed for some time and executed works for some local families. In 1732 he was in Bergamo where he painted the frescoes in the Colleoni Chapel in the cathedral with scenes from the life of St. John the Baptist. In 1736 he began work on frescoes in the Gesuati church in Venice, completed in 1739.

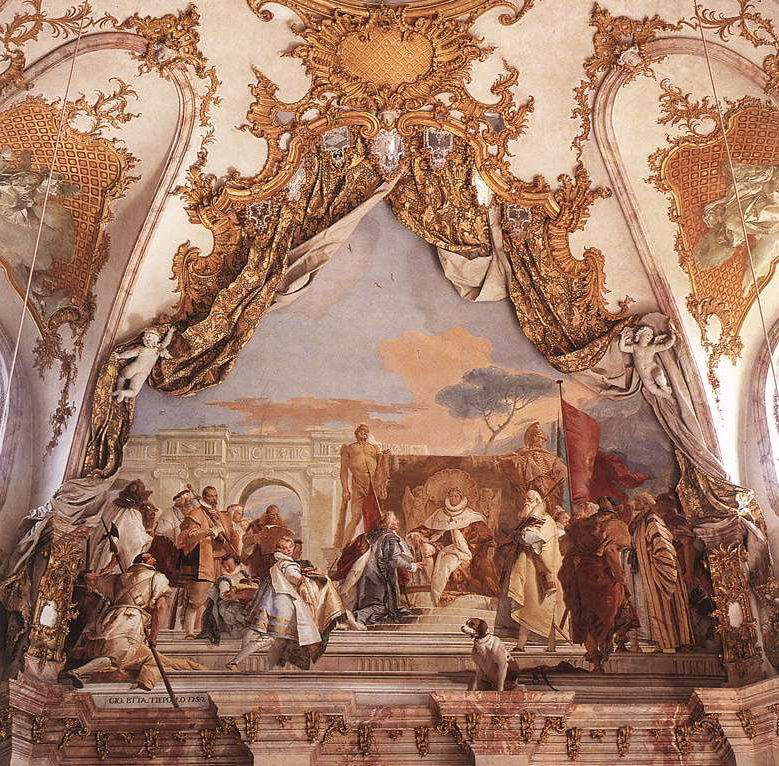

In 1737 the artist painted the Martyrdom of St. Agatha for the Basilica of St. Anthony in Padua, while in 1740 he was again in Milan, where he was entrusted with the fresco decoration of the rooms of Palazzo Clerici, home of the noble family of the same name. In 1743, Tiepolo met the man of letters and art collector Francesco Algarotti, for whom he executed several paintings with historical and mythological subjects. In Venice, in 1747, he began work on the fresco decoration of Palazzo Labia with the stories of Marcantonio and Cleopatra, completed in 1750. The following year, in 1751, the prince-bishop of Würzburg, Carl Philipp von Greiffenklau, called him to decorate in fresco some rooms of the famous Würzburg Residence. In 1753 Giambattista returned to Venice from Germany and four years later executed the frescoes at Villa Valmarana ai Nani in Vicenza. In 1761 he began painting theApotheosis of the Pisani family, a masterpiece of the mature phase that is in the Villa Pisani in Stra, near Venice. The work would be completed the following year and was the painter’s last work executed on Italian soil. In 1762, Charles III of Spain called him to Madrid where he became court painter, succeeding in the post another Venetian artist, Jacopo Amigoni. The painter settled permanently in Spain where he executed numerous works for the court, including the seven altarpieces for the convent of Aranjuez and several fresco decorations for the Royal Palace of Madrid, including the frescoes in the throne room. The artist passed away in Madrid on January 27, 1770. He is buried in the church of San Martín, but the artist’s tomb has been lost.

|

| Giambattista Tiepolo, Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew (1722; oil on canvas, 167 x 139 cm; Venice, San Stae) |

|

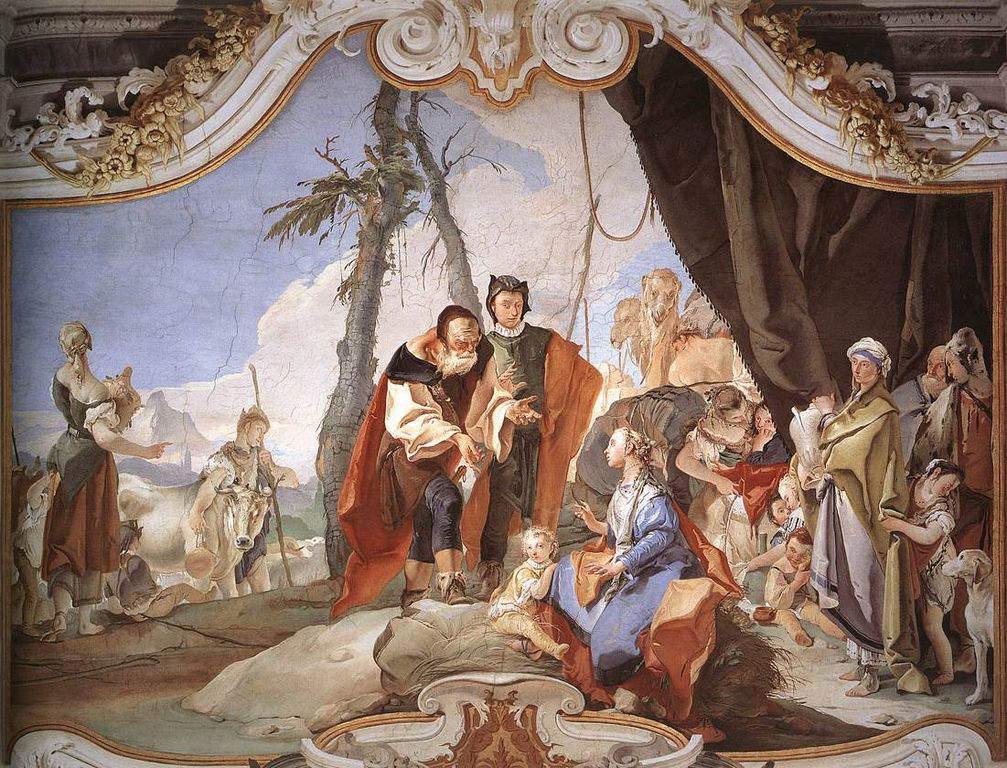

| Giambattista Tiepolo, Rachel Hiding the Idols (1726-1729; fresco, 500 x 400 cm; Udine, Palazzo Patriarcale) |

|

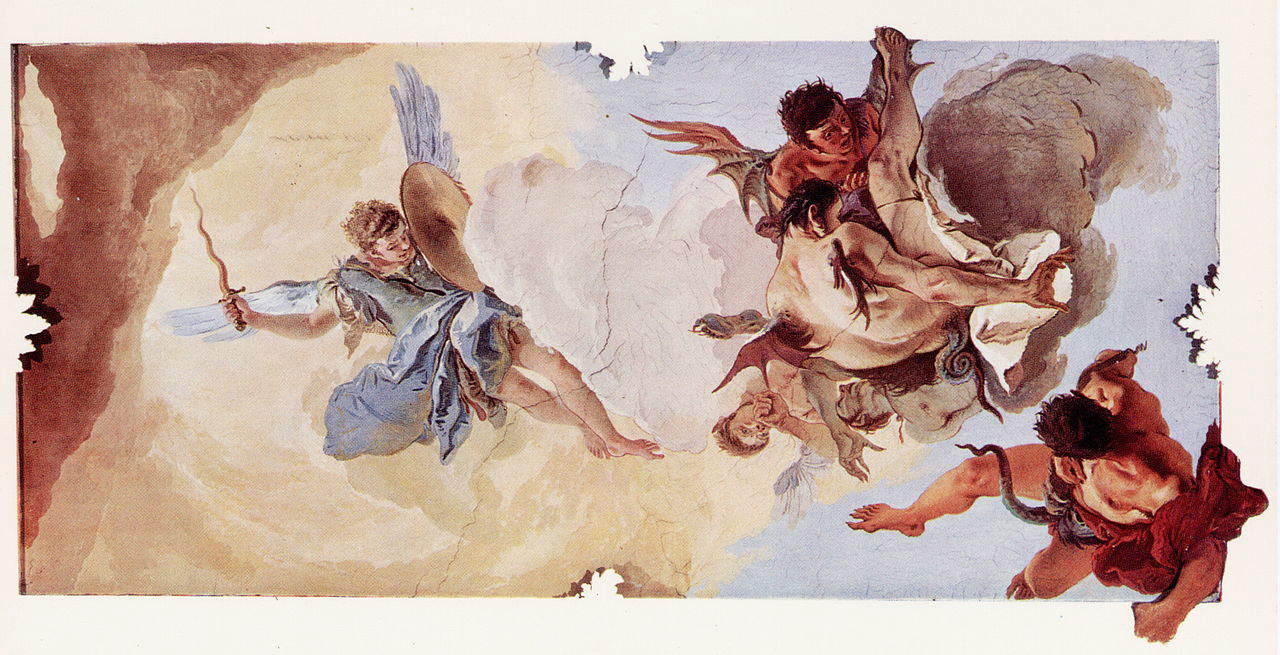

| Giambattista Tiepolo, Fall of the Rebel Angels (1726-1729; fresco, 200 x 250 cm; Udine, Palazzo Patriarcale) |

Our artist’s earliest known works are the apostles executed between 1715 and 1716 for the Ospedaletto church in Venice: the artist was not yet in his early twenties but was already executing works independently and, above all, demonstrating great confidence since from these paintings the artist broke away from the style of his master Lazzarini, from whom, however, Giambattista Tiepolo learned several fundamentals of art such as drawing and perspective, in order to approach Piazzetta and Bencovich with figures characterized by somber chromatics, by rapid painting almost in spots vaguely reminiscent of Guercino, and, at this stage, by great power, even drama, a reflection of the gloomy art of Venice at the time. The masterpiece of this phase, however, is probably the Martyrdom of St. Bartholomew, a work of 1722 that the artist executed for the church of San Stae in Venice as part of a cycle on the lives of the apostles in which all the greatest artists of Venice at the time participated, including Giovan Battista Piazzetta himself, Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini and Sebastiano Ricci. It is perhaps the most dramatic work in the artist’s entire output: the saint is chained, a henchman is beginning to skin the saint, and another henchman instead is holding him down. Note the extremely theatrical pose of the saint as he soars despite the chains restraining his impetus, as well as the artist’s technique, which tends to construct his figures with color spread quickly, almost in spots, and with light hitting the figures increasing the theatricality of the whole. It is precisely the theatrical component of Tiepole’s art that tends precisely to make the episode look like a mise-en-scène: a tendency quite common in Rococo art, and here moreover accentuated not only by the use of light but also by the artist’s choice to set the composition on diagonal lines.

The first work that breaks away from all previous experiences are the frescoes in the Patriarchal Palace in Udine, executed between 1726 and 1729, commissioned by the Patriarch of Aquileia, <DionisioDolfin: the artist decorated the vault of the Scalone d’Onore with the Fall of the Rebel Angels, the Gallery of Guests with stories from the Old Testament, and finally the vault of the Red Room with the Judgment of Solomon. In the first fresco, one immediately notices the graceful figure of the archangel appearing on a very light-colored cloud, a figure contrasted with that of the rebel angels who are already taking on the guise of devils and are falling from the sky trying to cling to the clouds. Despite their vigorous bodies, which are nevertheless contrasted with the archangel Michael who looks almost like a teenager, an expedient that makes the scene even more surreal, the impression one gets from this fresco is not one of power, but it is a feeling of lightness, for the fall seems almost like a dance, an act (as the Martyrdom of St. Bartholomew appeared). Each character holds a very precise position, and no matter how complex the patterns may be, each character always responds to canons of balance that as a whole govern the whole painting: in this case we can see, for example, that the work is sharply divided into two equal parts, the one on the left with the good angel and the one on the right with the bad angels, because one of the typical characteristics of Rococo art was also to seek a kind of balance in very complex compositional patterns. Tiepolo’s lightness here also appears in the scenes that decorate the Gallery of Guests, for example the one depicting the appearance of the angels to Abraham where the patriarch is kneeling in prayer, and the angels, as if in a dream, appear on the clouds embracing each other. This sense of lightness is enhanced by the use of very terse and delicate chromatics and by the details of the landscape painted lightly and with rapid brushstrokes (look, for example, at the trunk placed diagonally that fills the left part of the composition, which without that element would probably have appeared more unbalanced).

Among the most interesting achievements of his maturity it is possible to mention the frescoes at Villa Valmarana ai Nani in Vicenza: the undertaking was led by Giambattista together with his son Giandomenico and the inseparable Girolamo Mengozzi, who, as always, was in charge of the quadratures. The frescoes are literary-themed (the five rooms in which Giambattista Tiepolo worked were decorated with episodes from as many literary works (theIphigenia in Aulis, theIliad, theAeneid, theOrlando Furioso, and the Gerusalemme Liberata), and this gave the artist the opportunity to experiment with a great variety of repertoires that resulted in the possibility of declining his art in the most diverse ways. We have an example of this in the grand fresco where the sacrifice of Iphigenia is depicted. The painting is interesting because it is a tale of emotions: the bystanders who witness the sacrifice appear amazed at the miraculous appearance of the doe led by the two cupids so that she is sacrificed in Iphigenia’s place, and among them is Chalchas himself, the old man with the beard, who already has the knife in his hand to kill a half-naked and visibly distraught Iphigenia. One of the most intense figures is that of Agamemnon, Iphigenia’s father, whom we see on the far right as he covers his face with a cloak so as not to witness the killing of his daughter. It all takes place under a mighty temple of composed classical architecture, with Ionic columns, foreshortened to central perspective, for a most impressive illusionism that greatly enriches the pathos of the situation. Another masterpiece of perspective illusionism can be found in the room devoted to the Iliad, particularly in the fresco with Thetis consoling Achilles, who has retreated from the Trojan War in despair over the loss of Patroclus: a painted window opens onto a seascape with seagulls in flight and where Thetis can be seen arriving. Achilles sits naturalistically astride the window sill, facing the viewer’s point of view, for a remarkable piece of illusionism, among the best in eighteenth-century painting.

The late Tiepolo, on the other hand, can be well represented by theApotheosis of the Pisani Family, a fresco decorating the ballroom of the Villa Pisani in Stra, near Venice. The fresco dates from the years 1761-1762 and celebrates one of the great families of the Venetian patriciate, representing a sort of summa of all of Tiepolo’s art: the composition is divided into several parts, which complement each other harmoniously and according to a perspective foreshortening from below, with the center being occupied exclusively by a sky of a very clear blue, over which the light clouds begin to thicken, arriving from the sides of the painting and announcing the apotheosis of the family. Among the clouds appears the Virgin, who blesses the Pisani family, occupying one of the sides of the painting, while on the opposite side one notices the personifications of Asia and America alluding to the places where the family had begun to do business, and all around allegories and players to celebrate the Pisani. This blue sky also dilates the space towards infinity, according to a way of painting that originated inBaroque art, and this with the always surreal tones of Tiepolesque art, whose task is not to create a credible narrative, but to create an imaginary narrative, with the figures returning to place between art and the public that barrier that seventeenth-century art had attempted to break down by bringing the painted characters closer to the reality of the observers. The artist is fully aware of this, just as he is aware of living in a decadent society: not surprisingly, Tiepolo was also a fervent caricaturist.

|

| Giambattista Tiepolo, Heliodorus Sacks the Temple (1724-1726; oil on canvas, 195 x 231 cm; Verona, Museo di Castelvecchio) |

|

| Giambattista Tiepolo, The Investiture of Aroldo (1752-1753; fresco, 400 x 500 cm; Würzburg, Residenza) |

|

| Giambattista Tiepolo, Sacrifice of Iphigenia (1757; fresco, 350 x 700 cm; Vicenza, Villa Valmarana ai Nani) |

An immersion in the art of Giambattista Tiepolo can begin in and around Venice: visiting the church of San Stae (the Martyrdom of St. Bartholomew), the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, the Gallerie dell’Accademia, the church of Sant’Alvise, and the Museo del Settecento Veneziano at Ca’ Rezzonico will already give you an idea of his art, which can be completed with a visit to the Villa Pisani in Stra, where you can admire Tiepolo’s late masterpiece, theApotheosis of the Pisani family. Outside the Veneto, major masterpieces include the frescoes in the Palazzo Patriarcale in Udine, the youthful ones in Villa Baglioni in Massanzago (near Padua), those in Villa Valmarana ai Nani in Vicenza, and those in the Tapestry Gallery of Palazzo Clerici in Milan. His works can also be found in the Colleoni Chapel in Bergamo (the frescoes with the stories of John the Baptist), in the church of Tutti i Santi in Rovetta, near Bergamo (which houses the All Saints Altarpiece), at the Musei Civici in Padua, at the Galleria Nazionale in Parma, at the Museo di Castelvecchio in Verona, and in Udine at the Cathedral and in the Musei Civici of the Friulian city.

Outside Italy, Tiepolo’s major masterpieces are the decorations of the Würzburg Residence and those of the Royal Palace in Madrid. His works can also be found at the Prado and the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, the Louvre, the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, the Staatliche Museen in Berlin, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the National Gallery in London, the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga in Lisbon, the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh, and the Art Institute of Chicago.

|

| Giambattista Tiepolo, life and works of the great Rococo artist |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.