Paul Cézanne (Aix-en-Provence, 1839 - 1906) belonged to the post-Impressionist current. With his works, he laid the foundations for Cubism and, more generally, for 20th-century art, especially because of the formal simplification that formed the foundation of many avant-garde movements of later periods. The painter did not have a docile nature, and evidence of this was his bitter relations with his father, who wanted him to be a doctor of law, but the young artist rebelled in order to follow his passion: art. Few were the “chosen ones” who came into the painter’s good graces, among them the artist Camille Pissarro, with whom he had a long friendship and strong artistic complicity. Less fortunate, however, was the writer and friend Émile Zola, who after publishing one of his novels was harshly criticized by Cézanne.

If in human relations Cézanne was not particularly adept, the opposite can be said of his art, which knew how to add an extra piece to the fruitful artistic experiments that were taking place in the times in which the artist worked. At first close to the Impressionists with whom he frequented the Café Guerbois in Paris, Cézanne soon moved away from them in order to develop a personal style, a more scientific and reflective painting technique that could give art its legitimate autonomy. For most of his life the French painter remained in his country home in Provence, although, in his youth he was much attracted to the Parisian boulevards and the cafes of Montmartre and Montparnasse. In the French countryside he had many stimuli and subjects to represent, many of which became his hallmarks, such as the Sainte-Victoire mountain, or the many still lifes and portraits.

|

| Paul Cézanne, Self-Portrait with Cap (1875; oil on canvas, 53 x 39.7 cm; St. Petersburg, Hermitage) |

Paul Cézanne was born on January 19, 1839, in Aix-en Provence to Louis-Auguste and Anne Elisabeth Honorine Aubert in a wealthy family. He studied at the Bourbon College in his hometown, which in 1952 Cézanne formed a long friendship with the famous writer Émile Zola, who was destined to become one of the most sensitive and well-known interpreters of 19th-century French literature. His father wanted his son to study law, but the young man in 1860 abandoned his studies to devote himself to art, an activity also supported by his mother and sister. Although his father did not appreciate his son’s choice to become an artist, he allowed him to attend the best schools in France, thanks to the economic affluence the family enjoyed. After this initial approach to the art world, Cézanne quickly matured his desire to move to what was the true capital of art: Paris. In 1861 he finally obtained permission from his father to travel to the French capital, on the condition that his son would be able to enter one of the most famous art schools such as the École des Beaux Arts. The young painter failed the entrance exam and attended the freer Académie Suisse: here Cézanne befriended Édouard Manet, Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, representatives of a new way of painting, far from the traditional one that was taught in the academies. During this first stay, his visits to the Louvre were very frequent, where he admired the masterpieces of Caravaggio, Titian, Rubens, Michelangelo and Velázquez but also the most modern trends in art of the time. Between 1865 and 1867 Cézanne tried many times to present his works at the Salon, which, however, were continually rejected.

If there was little satisfaction in the artistic sphere, the artist at least found comparison in love: in fact, in romantic Paris in 1870, Cézanne met Hortense Figuet, a young model whom he married and by whom he had a son, Paul. Two years later, Pissarro invited him to his country home in Pontoise, and during the stay he learned to paint d’après nature, that is, to paint nature by observing it outdoors. Enthusiastic about the stay, Cézanne decided to buy a house near his friend Pissarro, and it was here that he met the doctor Paul Gochet, his future collector. One of the works destined to become very famous, The Hanged Man’s House (1873), also dates from this period. With Pissarro he began to frequent the Café Guerbois, a meeting place for what would become the "Impressionists," who in 1874 invited him to take part in the first Impressionist exhibition held in photographer Nadar’s studio in Paris. On that occasion he managed to sell a few paintings, although there was much negative criticism and strong hilarity he unleashed among the visitors. An exception was Victor Chocquet, an art-loving customs officer who was very independent in terms of aesthetic tastes and bought some works by Cézanne. Chocquet greatly admired the artist’s paintings, and a beautiful friendship was established between the two. In 1877 he participated in the second exhibition of the Impressionists: this was the last time that Cézanne joined the exhibition, a consequence of the fact that the painter did not agree with their way of making art, which he considered too “retinal,” that is, too adherent to the real datum.

After the 1877 exhibition, the painter retired to Provence, where he stayed for twenty years in the famous Jas de Bouffan studio (the subject of some of his canvases), isolated and absorbed in his art. In 1886, after his father’s death, he inherited a sizeable fortune, which meant that he did not have to worry about making money from his art. In the same year his friendship with Zola became increasingly bitter, and the final break came following the publication of the writer’s book The Opera: the novel told of a failed artist, with all his dreams and miseries, and in it Cézanne immediately recognized himself. This was the straw that broke the camel’s back: the two childhood friends never spoke again.

In the 1890s, Cézanne began work on one of his most famous works, The Card Players . In 1895 the French art dealer Ambroise Vollard organized an exhibition on Cézanne, which was decisive because from that moment his notoriety rose sharply. In 1897 his mother, to whom he was very close, died, and despite the sale of the Jas de Bouffan house-studio, however, he never had a real detachment from his beloved Provence. Cézanne, in fact had a small apartment in the center of Aix and a small studio with a small window that gave directly onto one of the favorite subjects of his paintings: the Montagne Sainte-Victorie. Meanwhile, the reputation of the solitary and brilliant artist began to circulate throughout Europe, and there were many invitations to participate in exhibitions: nonetheless, the artist, in almost voluntary isolation, locked himself away permanently in search of new artistic experiences.

Unlike many artists who produce many works in their youth, Cézanne, not being an instinctive but a methodical and reflective artist, was able to produce great masterpieces during his maturity: in fact, in 1904, an entire room was dedicated to him at the Salon d’Automne, which was also seen by the young George Braque and Pablo Picasso, who were about to found Cubism. The celebrity he achieved, however, was not enough for him: in fact, the painter was always tormented by the idea that he had not achieved his goal. Cézanne wanted to paint what he thought, and this idea plagued him throughout his life. Death came suddenly, and in 1906 he died of pneumonia.

|

| Paul Cézanne, Vase, Coffee Pot and Fruit (Still Life in Black and White) (1867-1869; oil on canvas, 64 x 81 cm; Paris, Musée d’Orsay) |

|

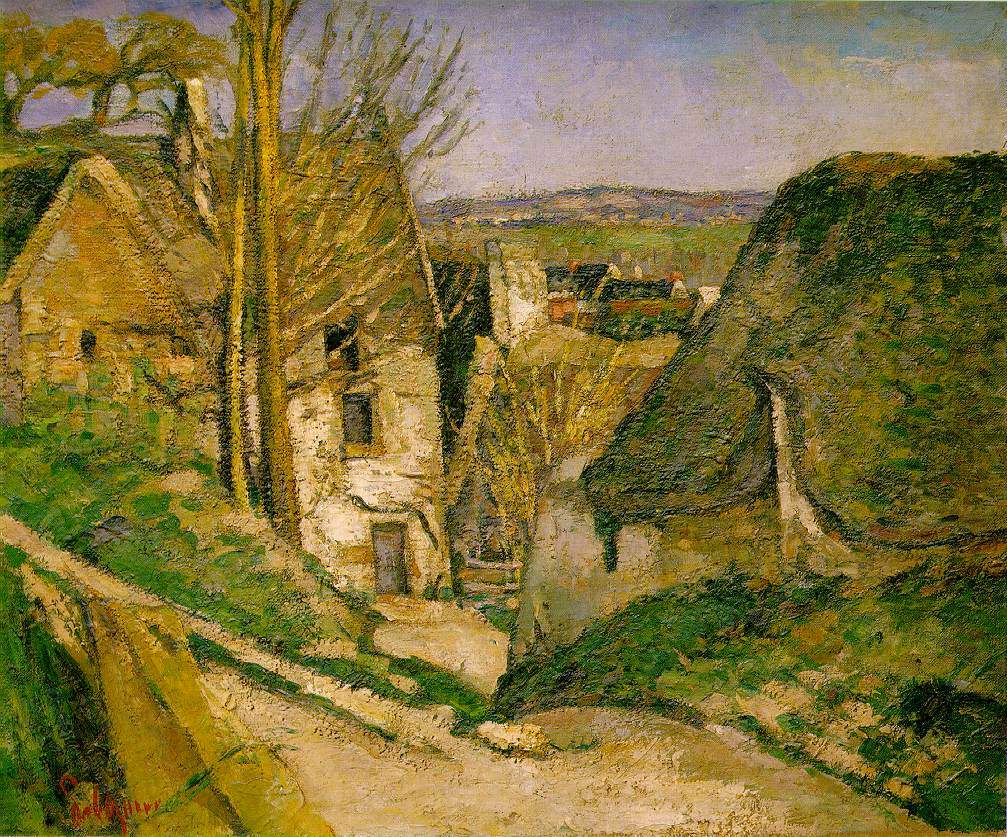

| Paul Cézanne, The House of the Hangman (1872-73; oil on canvas, 55 x 66 cm; Paris, Musée d’Orsay) |

|

| Paul Cézanne, The Maincy Bridge (1879-80; oil on canvas, 58 x 72 cm; Paris, Musée d’Orsay) |

|

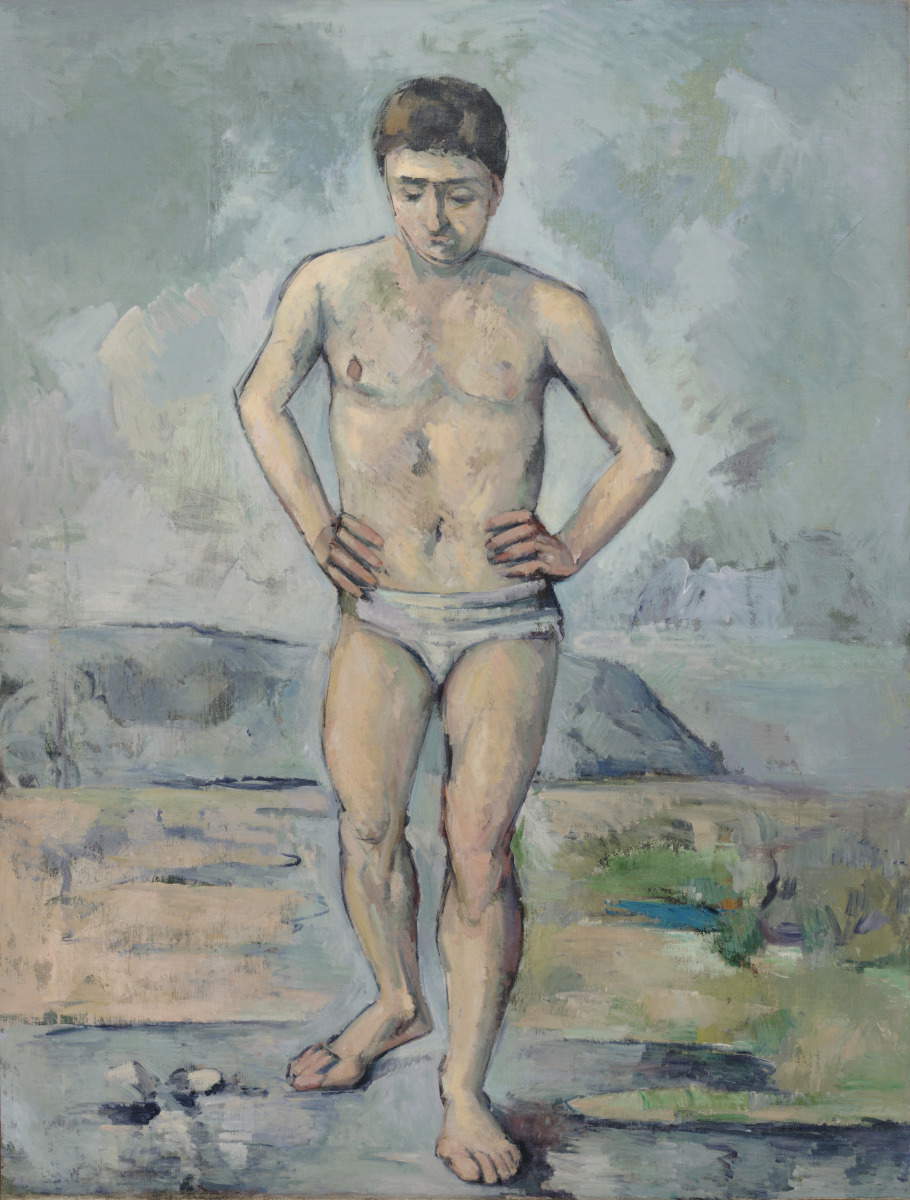

| Paul Cézanne, Bather (1885; oil on canvas, 127 x 96.8 cm; New York, MoMA) |

Cézanne’s painting was methodical and reflective: the artist did not wish to paint what the eye sees, as the Impressionists did, but the logical and structural construction of the painted subject. The painter sought a synthesis of forms; in fact, according to the painter, nature is made up of geometric shapes: cylinders, cones, and spheres. Regardless of the way nature is structure what the mind can perceive are the geometric shapes, which is why, according to the painter, it is impossible to reproduce nature as it is made.

Cézanne’sfavorite subjects were still lifes, portraits and landscapes. Still lifes offered Cézanne a rich range of forms that allowed him to investigate reality analytically and scientifically. The tables set by Cézanne were, at first, very poor, not as rich as Manet’s, and poor were also the things he arranged on them as in Vase, Coffee Pot and Fruit (Still Life in Black and White) of 1867-69, one of the artist’s earliest still lifes. On the bare table rests a brown carafe, a candle, a white handkerchief with a knife on it, and onions and a lemon. Apparently it looks like a messy and temporary composition, however, the artist placed his attention on the static and composed character which is followed by stillness and silence. The objects demonstrate their inherent volumetric power, also given by the drafting of the color, made with strong impasto and mercando the outlines in black to give the objects more volume. By contrast, the work Terrapieno, which was made in Provence, dates from 1870. The palette lightens, compared to the still life of 1867, and this is a sign of his closeness to the Impressionist painters, although the painter does not renounce the firm, dense brushstrokes that restore full autonomy to his works. The Hanged Man’s House (1872-73) was offered at the first Impressionist exhibition in photographer Nadar’s studio in 1874. The work is the result of advice given to Cézanne by his friend and painter Camille Pissarro, who in fact began painting en plein air (in the open air) and lightening his color palette. In the foreground, on a sharp diagonal line, is a country road, in the center is depicted a small house of preceded by long, slender trees, to the right stands another house, and between the two can be seen a built-up area, behind which hills can be glimpsed on the horizon. From the volumetry of the houses one can immediately assume an initial attempt to simplify the forms and thus an attention that emerges more and more in the definition of volumes.

In addition to still lifes and landscapes, Cézanne devoted much time to portraits and self-portraits. In Self-Portrait with Cap (1875), the painter depicts himself with his face to the left, where his gaze is lost. His somewhat unkempt appearance, long hair and unkempt beard are evidence of his irascible but also closed, reserved and solitary character. The artist is wearing a dark coat and cap, and on the right side a landscape can be glimpsed. Here again one can see the artist’s need to impose a certain geometricity, although the painting was made in the in which he adhered toImpressionism. A work of extraordinary freshness, however, is The Maincy Bridge (1879-80), in which Paul proceeds by small, energetic brushstrokes that define space. The composition is constructed with the usual precision and structural rigor that characterizes his paintings: the “dowels” of color build up the bridge, the trees and all the elements represented. In the 1880s his artistic research on form and his desire to restore solidity to nature reached a high level, and an example of this is the Bather (1885) whose solitary body emerging from the bare background proceeds toward the viewer, with hands on hips and face turned downward that is completely absorbed in itself. The figure also dialogues very well with its surroundings; in fact, its colors echo those of the water, the sky, and the mountain on the horizon.

Cézanne also accentuated the solidity of the forms in the portrait of Madame Cézanne in the Yellow Armchair (1888-90), a beautiful woman with dark eyes and brown hair is wrapped in a red dress who sits in an armchair and turns her gaze to the right: this is his wife Hortense Fiquet. Here the artist renders the delicate female figure in a pure play of volumes, which leave little room for emotional expression, as in fact is perceptible from the face: the head is an almost perfect oval and the arms take on cylindrical forms. In 1888 Cézanne returned to Paris with his wife Hortense and son Paul, remaining there until 1890. During this period he devoted much of his time to the human figure; in fact, he decided to hire a professional model to make paintings. The model in question was the young Italian Michelangelo Di Rosa who was depicted in the painting The Boy with the Red Waistcoat (1888-1890) in which the artist studied the relationship between the human figure and space. The boy appears in the traditional position of melancholy: seated at a table, the young model is facing to the right and his face is supported by his left arm. He is wearing a white blouse and vest (from which the work’s title is derived), and blue pants. Wide swathes of color make up the painting; there are stretches, in fact, where the artist resorted to spatulas to spread the color more sharply. It is precisely the color that builds the image and the volumetric forms that are achieved through the juxtaposition of color dowels. The melancholy that invests Michelangelo Di Rosa was something that greatly impressed Amedeo Modigliani, who had the opportunity to see the painting in the room that the Salon d’Automne in 1907 dedicated to Cézanne.

The portraits and self-portraits were many, and the artist often asked his models to stand still for hours on end, as in the case of Ambroise Vollard, his dealer, who reported that he posed a hundred times, and that a lot of time could pass between brushstrokes. In the portrait of Ambroise Vollard (1899) the elegantly dressed man is sitting on a chair with his legs crossed and a book in his hand. The merchant’s face, framed by a well-groomed beard, looks pensive. The few details on the face make the gaze almost absent, and the static background treated with a rather dark palette is interrupted by a window, behind which a fragment of metropolitan life can be seen. The colors that prevail are ochre and brown, except for the shirt and the window that faces outside, from the latter comes the light that illuminates the scene. A very famous work is the Two Card Players (1892-95), which focuses on the cerebral play of the two players. Throughout the painting there are three basic colors: blue, yellow and red. The painting is a variation of the many versions that Cézanne made, taking the peasants of Aix as his model: however, there are no folkloric references since the painter’s interest is solely in the game. The painting has a very geometric scheme giving the characters a classical note and is built on a grid made of horizontal lines given by the table top and window and vertical lines given by the bottle placed in the center, the left player’s chair and the table legs. The painter pays special attention to the use of color, which here becomes dense matter that creates space, the tones were used to give form and space to the work. Compared to the early still lifes in which Cézanne sought sobriety and static composition, the later ones were a more complex and articulate elaboration, an example being Still Life with Oranges and Apples (1899) in which the use of color bursts forth. The space is invaded by the oriental fabric, a white tablecloth rests on the table with apples and oranges on it arranged in different ways and places. The entire painting is built on a diagonal starting from the left and going to the right, and this trend is also accentuated by the arrangement of the fruit, which is arranged in a pyramidal fashion. The difference between depth and surface is masked, and everything seems to stand on the usual plane, but without giving up its volumetric autonomy.

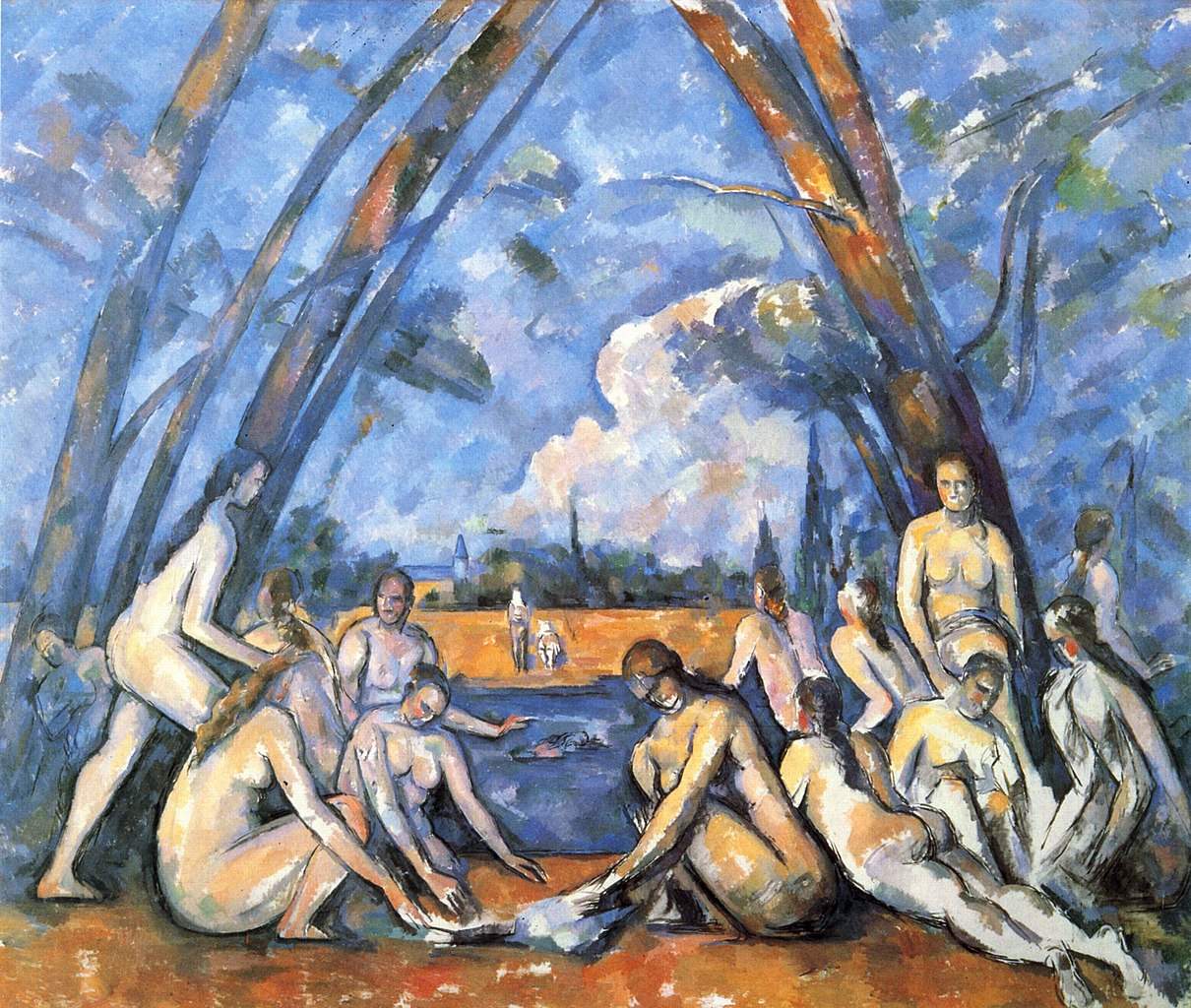

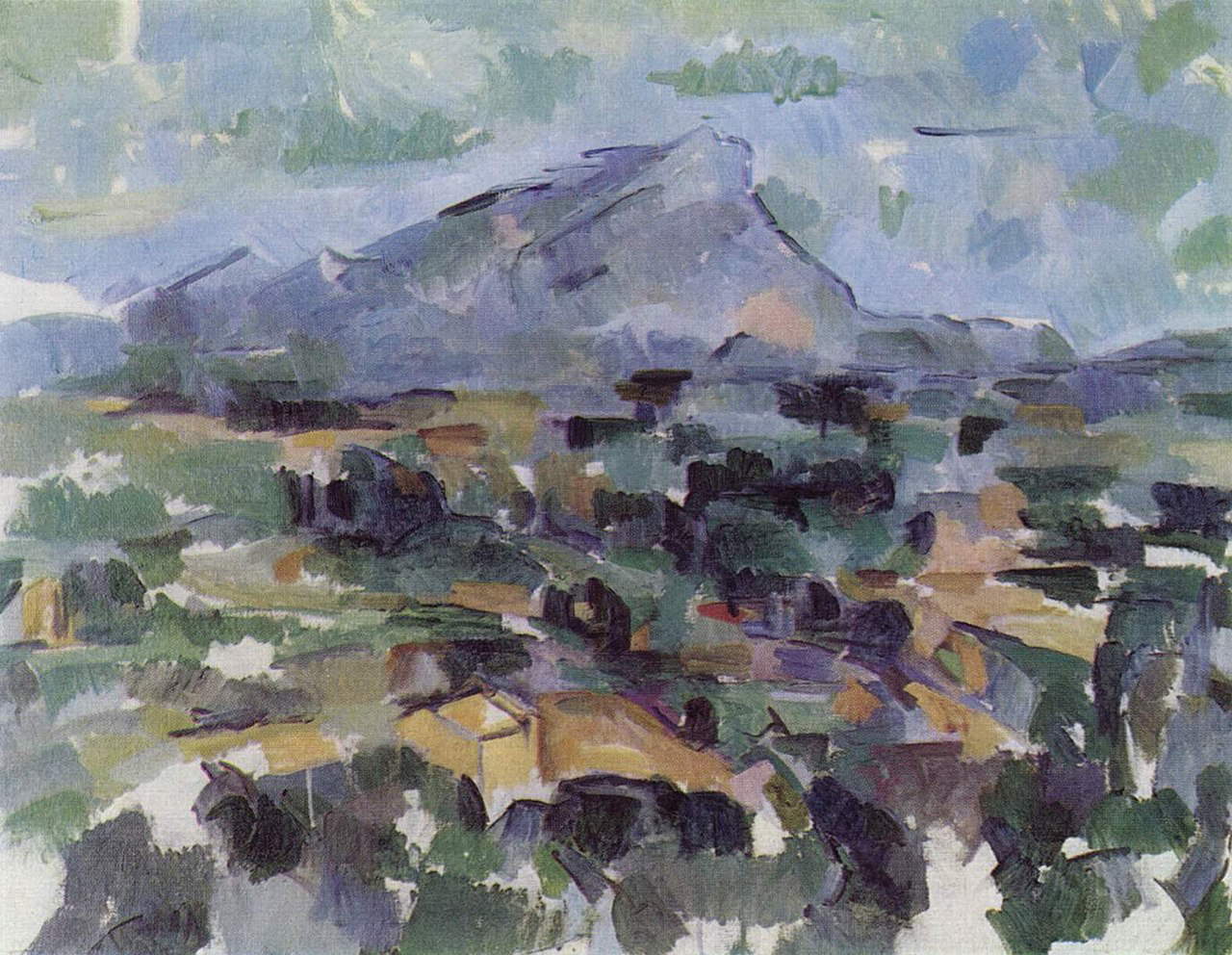

TheBatherstheme was deeply studied by the French painter, who devoted about two hundred studies to it, which led to three large canvases: the first is at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the second at the National Gallery in London, and the last at the Barnes Foundation, also in Philadelphia. The first museum has the largest version, which Cézanne made between 1899 and 1906. The Large Bathers consists of fourteen figures divided into two groups and set in an almost idyllic environment (note the bluish light and the wide, suave landscape). The female body that loses its harmonious and delicate forms here becomes pure volume that punctuates the space, and the face loses all hint of expressiveness. Beyond the imposing trees behind the figures is a sheet of water from which the viewer’s gaze turns toward the horizon. Cézanne depicts a timeless world in which nature and man almost merge. The artist’s desire was to give art its own autonomy from the real world, and in this canvas Cézanne seems to be very close to this purpose. If for many artists their inspiring muses were often fascinated models and women, it was otherwise for Cézanne, who in the last years of his life studied almost obsessively the mountain of Saint Victoire in Provence: each time he painted and analyzed it differently, using different techniques and changing the color palette. The mighty mountain dominates the valley near Aix-en-Provance; its beauty fascinated the painter who tried to capture its geometries and volumes. Sainte-Victoire Mountain from the Southwest (1892-95) was one of the first canvases Cézanne made with this subject. In the painting, although still quite tied to natural elements, it is already possible to discern interventions that synthesize forms such as, for example, the profiles of the houses that have become windowless volumes. Ten years later, Cézanne reintroduced the same subject: Mountain of Sainte-Victoire (1904-1906). Here the painter assiduously investigated the relationship between form and color. The contours are blurred, there are no longer houses but patches of color that hint at the few figurative elements present. Nature is dominated by geometric forms, and the imposing mountain is wrapped in a blue sky, all forms are broken up by the broad brushstrokes. Cézanne put all his efforts on the art, sacrificing the subject, his focus prevailing not so much on what is seen (as the Impressionists did) rather on the internal rules of the mind: a principle, this, that was the basis of all 20th-century art and for which Cézanne’s contribution was fundamental.

|

| Paul Cézanne, Madame Cézanne in the Yellow Armchair (1888-90; oil on canvas, 80.9 x 64.9 cm; Chicago, The Art Institute of Chicago) |

|

| Paul Cézanne, Two Card Players (1892-95; oil on canvas, 47.5 x 57 cm; Paris, Musée d’Orsay) |

|

| Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Oranges and Apples (1899; oil on canvas, 74 x 93 cm; Paris, Musée d’Orsay) |

|

| Paul Cézanne, The Great Bathers (1906; oil on canvas, 208 x 251 cm; Philadelphia, Philadelphia Museum of Art) |

|

| Paul Cézanne, Sainte-Victoire Mountain (1905; oil on canvas, 68 x 81 cm; Zurich, Kunsthaus) |

Many of the painter’s works can be seen at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, where some of his most famous canvases, such as Self-Portrait (1880), Bathers (1890), and Still Life with Apples and Oranges (1899) and The Two Card Players (1892-95), are kept. Also in Paris, Portrait of Madame Cézanne (1890) is instead kept at the Musée de l’Orangerie.

At the Museum of Modern Art in New York many still lifes and Bather (1885) are on view. The Philadelphia Museum of Art has the work The Great Bathers (1906). The French painter’s works can be seen at the Puskin Museum in Moscow, which holds a large collection of his works, among the most famous being Smoker with Pipe (1891), and Self-Portrait with Beret (1875).

|

| Paul Cézanne. Life and works of the painter who invented 20th century art. |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.