Renato Guttuso (Bagheria, 1911 - Rome, 1987) was one of the most important Italian artists of the 20th century, and his name is among those that marked the history of Italian art in the second half of the 20th century. To find the prodromes of Guttuso’s art, it is necessary to go back in time, to when the Sicilian painter was still a child, that is, to the end of World War I, in 1918: the event had greatly influenced the feeling of the artists and their operational choices. Many of them, having enlisted in the army, saw with their own eyes the brutality of war and, once they returned home, changed their way of painting; others, such as the sculptor Umberto Boccioni and the architect Antonio Sant’Elia, would never return, having died during the war events. The war produced both the effect of a loss of confidence, which many had placed in it, and the channeling of artistic instances around a common ideal: the need for a recovery of classical languages and iconographies.

Two trends emerged after the First World War: the Novecento group, stemming from the legacy of early metaphysical painting (metaphysics is an experience, matured in the 1910s, of redefining figuration, which only from the 1920s, in its exhaustion, would be considered an artistic current) and a series of groups reacting to Novecento. Novecento established itself in Milan in 1922 and consisted of seven artists (Anselmo Bucci, Leonardo Dudreville, Archille Funi, Gian Emilio Malerba, Piero Marussig, Ubaldo Oppi, and Mario Sironi), at the initiative of art critic and journalist Margherita Sarfatti. The artists had different personalities, but their desire was to move away from the avant-garde, for example from Futurism, which had believed so much in the positive scope of the war. Artists in general, not just those in the Novecento group, express a desire to rethink, for example, classical statuary (480-323 B.C.), Renaissance art (fifteenth and sixteenth centuries), but also artists closer chronologically, such as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (Moutauban, 1780 - Paris, 1867), a French painter and a careful scholar of ancient art.

Among those opposed to Novecento is Renato Guttuso, a leading exponent of Corrente, an art movement whose name derives from Corrente di vita giovanile, a magazine founded in 1938 in Milan on the idea of the painter Ernesto Treccani (Milan, 1920 - 2009). The goal of its members was to reconcile political life with an idea of independent art, freed from the power of the fascist regime. Among the group’s protagonists are painters Emilio Vedova, Aligi Sassu, Ennio Morlotti, Renato Birolli and, of course, Guttuso and Treccani. The main references are turned toward the French nineteenth century, the International Avant-Garde, arousing particular attention to individual personalities not associated with a precise artistic movement, such as Van Gogh and Pablo Picasso. Also in 1938, the group’s manifesto was published, but the experience was already partly over by 1943, with the suppression of the magazine by the fascist regime. Guttuso and Sassu are shown to be displeased with the experience of the Novecento group, which was considered an enemy, given its close proximity to Fascism. While the raison d’être, initially, is to propose modern art that does not break with tradition, it is later Mussolini who uses the Novecento group to promote the regime’s art, making the movement conservative in its outlook. Once the war was over, Guttuso’s art would gain increasing political weight , configuring itself as one of the most interesting experiences of its time.

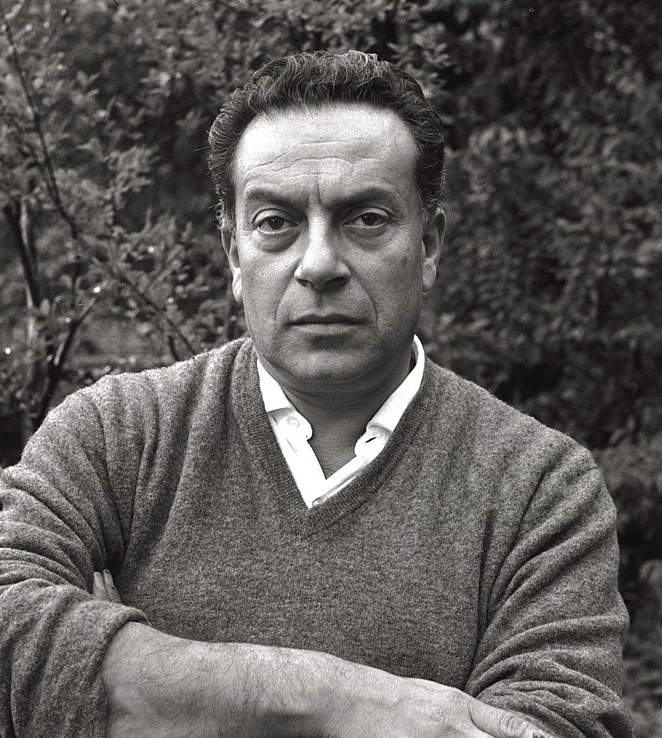

|

| Renato Guttuso in 1960 |

Renato Guttuso was born in Bagheria, Sicily, on December 26, 1911. He immediately came into contact with painting through his father, also an artist; later he attended the studio of painter Emilio Murdolo. The landscapes, the mountainous reliefs of his land, would inspire Guttuso throughout his career. At the age of thirteen he already signed several works, mainly related to landscape painting. In the years to come he moved from his hometown to study in Palermo, at the workshop of Pippo Rizzo, a sculptor and painter close to Futurism.

In the 1930s, Guttuso left the island for Rome, where he exhibited at the Quadriennale Nazionale d’Arte, and then the following year, 1932, he arrived in Milan, a guest at the Galleria del Milione along with other Sicilian artists. During his military service, a few years later, he had the opportunity to meet Lucio Fontana, who later became the founder of Spatialism, Elio Vittorini, later the creator in 1945 of the magazine Il Politecnico, but also the famous man of letters Salvatore Quasimodo; the philosopher Edoardo Persico and many others. These are the years in which the artist matures a political consciousness that will influence the creation of his works, steeped in symbols and ideologies. 1939 was the year he moved to the capital, Rome, a source of inspiration and an opportunity for continuous study, but which he had to leave a few years later due to political complications. In those years, Mussolini pursues an increasingly harsh policy of repression in Rome, against opposition parties; Guttuso, a strong anti-fascist, is forced to leave the city. In 1945 he is in Paris where he meets Pablo Picasso, considered a friend but also an ever new stimulus for his works, the Spanish artist being one of the most varied twentieth-century personalities in terms of technical experimentation.

Fundamental is, in the postwar period, his membership in the Fronte Nuovo delle Arti art group (1946-48), to give voice to all artists who, because of fascism, could not freely exercise their art in Italy. Leoncillo Leonardi, Morlotti, Vedova, Corpora, Fazzini and others were members. Guttuso’s was a very dynamic life, an artist who traveled both around Italy and abroad, gaining recognition, important collaborations for theater sets, Italian and international magazines, as well as an invitation to exhibit several times at the Venice Biennale. Since 1965 he has lived and worked in Rome at Palazzo del Grillo, never abandoning his political career (his communist faith had never waned: in fact, as early as 1940 he had joined the underground Communist Party of Italy), culminating in his election as senator in the PCI, the Italian Communist Party, in 1976. His 1972 masterpiece, The Funeral of Togliatti, now kept at MAMbo in Bologna, is a kind of manifesto of communist painting. Instead, in 1974 he painted Vucciria, the masterpiece dedicated to the well-known Palermo neighborhood. On January 18, 1987, he passed away in Rome, at the age of seventy-five. In his career, Guttusot collected no fewer than four participations in the Venice Biennale (1948, 1950, 1952, 1995) and three in the Rome Quadriennale (1931, 1935, 1937), as well as solo exhibitions at Palazzo Grassi in Venice (1981), Milan’s Palazzo Reale (1985), the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam (1962), and the Kunstverein in Frankfurt (1975).

|

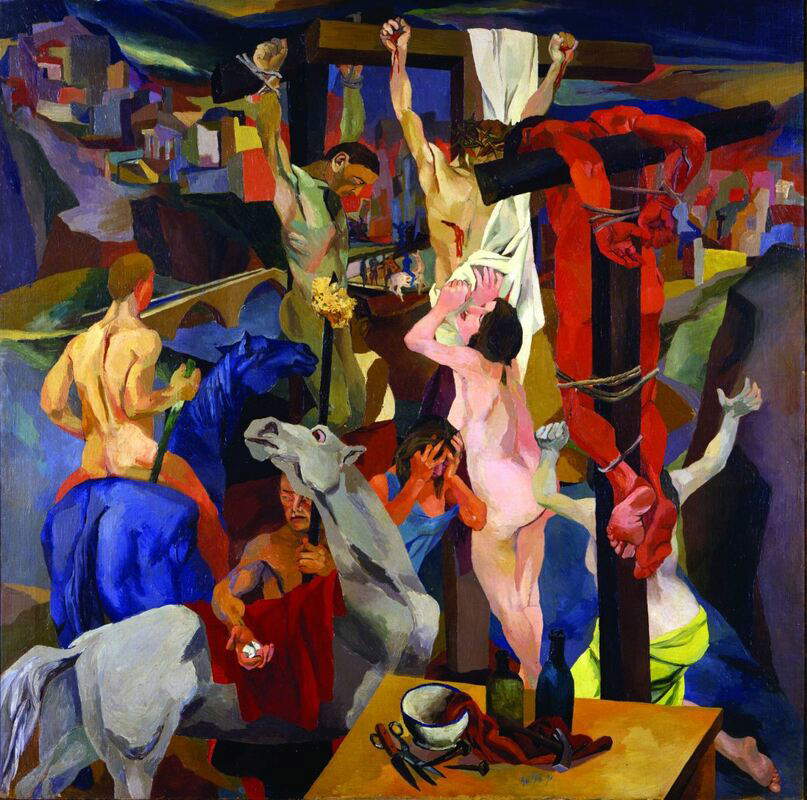

| Renato Guttuso, Crucifixion (1941; oil on canvas, 200 x 200 cm; Rome, National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art) |

|

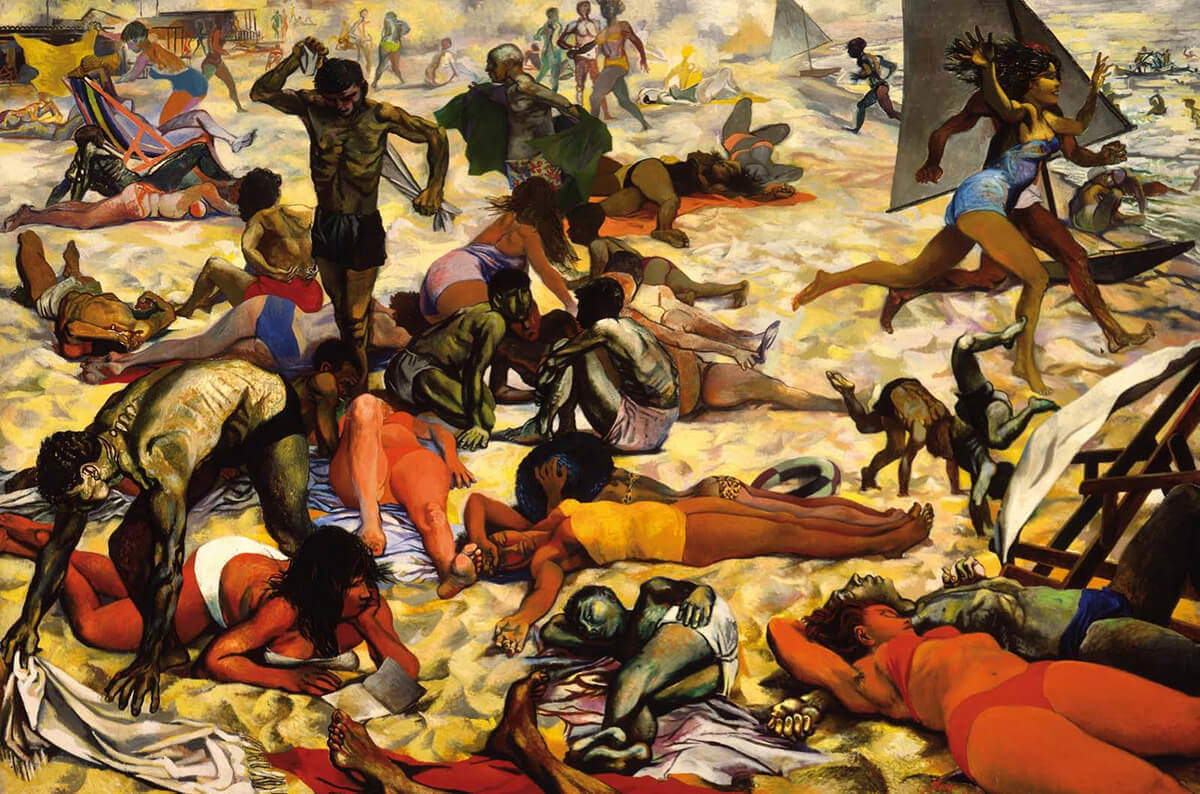

| Renato Guttuso, The Beach (1955-1956; oil on canvas, 301 x 452 cm; Parma, Galleria Nazionale) |

|

| Renato Guttuso, Vucciria (1974; oil on canvas, 300 x 300 cm; Palermo, Palazzo Steri) |

In the absence of an adequate language more than another to make politically engaged works of art, Guttuso opted for freedom of expression. His idea is clear when reading the following words, “To express oneself with absolute sincerity and in community of spirit, free from all preoccupations, whether archaic or neoclassical, whether metaphysical or intellectualistic. Primitive, by necessity, because born in an age of beginning” (from Speeches on sincerity: the young, in The Hour, April 10-11, 1933). One of his best-known works is the Crucifixion of 1941. A work much criticized, especially by the Church, for the “disrespectful depiction” of Christ on the cross, according to the Bergamasque curia. The colors seem dull, almost metallic, the deformed bodies resembling caricatures; the poses assumed by the figures are anti-naturalistic and elongated, daughters of the influence of Picasso’s work, Guernica. Guttuso continues with his unconventional interventions through traditional techniques, such as drawing, widely used by the artist (the design part, in fact, is also the tool with which the artist practices). In the 1950s, Guttuso is thus wont to take a drawing and intel it, presenting it as if it were a painting.

Some Guttuso scholars, in particular Enrico Crispolti, an Italian art critic and historian, have found difficulties in attributing works to the artist with certainty, even though he was still alive at the time of the investigation; what troubled the critic and the artist himself was the quantity of drawings made: so many that they could not distinguish an original from a fake. A problem that not even the intervention of Guttuso himself could solve. Many artists praised the Sicilian artist, first and foremost his friend, writer, poet and director Pier Paolo Pasolini, but LeonardoSciascia’s accounts are also relevant to understanding how the artist acted. A friendship, the latter, interrupted by a political argument.

From the writings, it is clear that in his works the link with the land occupies a fundamental place, albeit one that is constantly evolving with his poetics. On an early work, La fuga dall’Etna, 1938-1939, Sciascia draws parallels with attachment to one’s origins, a pivotal concept in Giovanni Verga: “The poetics is for both of them to simplify human passions, but Verga’s starts from a return, Guttuso’s from a flight [..] the man attached to the rock of misery and affections, suffers as and as much as the man on the run, the man in revolt of Guttuso.” Guttuso, moreover, made some illustrations for Verga’s I Malavoglia in 1978. Even Maurizio Calvesi in his 1985 essay Guttuso e la Sicilia writes about closeness to the homeland: “few artists, like Guttuso, are so deeply marked by their origin, and not only in the nature of the themes, but in the same linguistic choices.”

In the 1940s, Guttuso’s art changed: the realism and dramaticism of his paintings became more pronounced, and in the immediate postwar period his interest in men and women of the people became alive. Guttuso, in those years, produced two versions ofOccupation of Fallow Lands in Sicily, one from 1947 (better known as Peasant Marseillaise), and the other from about 1949; a technical change on the artist’s part is evident. The two works do not even appear to be so few years apart. In the first, the influence of Picasso’s Guernica, an artist he knew and with whom he befriended in 1945, emerges: the figures are so close together that they almost overlap, the faces are square, the expressions cold, often without facial features; the human features are totally deformed, almost as if it were a still life. In contrast, the second version is clear and legible to the viewer, as the figures are distinct from each other as well as from the surrounding landscape. One of his last works is 1983’s The Flight into Egypt, for the chapel of the Sacro Monte in Varese, where unmistakable are the colors, which come from his Sicily. Of particular relevance is also the production with a political character: the masterpiece in this sense is I funerali di Togliatti, a 1972 painting depicting the funeral of the secretary of the PCI, Palmiro Togliatti, celebrated in Rome in 1964: Guttuso, in order to translate his political commitment into images, realizes a fictional funeral described, however, realistically. In fact, at the funeral we see some figures (such as Lenin, Picasso, Neruda) who did not actually attend Togliatti’s funeral (Lenin moreover died forty years earlier) but whom the artist considered leading figures of the progressive forces.

|

| Renato Guttuso, Peasant Marseillaise (1947; oil on canvas paper, 151 x 208.5 cm; Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts) |

|

| Renato Guttuso, Occupation of Fallow Lands in Sicily (1949; oil on panel; Dresden, Gemäldegalerie) |

|

| Renato Guttuso, The Funeral of Togliatti (1942; oil on canvas, 340 x 440 cm; Bologna, MAMbo) |

There are many museums in Italy that preserve works by Renato Guttuso: in fact, the Sicilian was a very prolific artist and his art can be appreciated throughout Italy. The landmark museum for the artist is the Museo Renato Guttuso in Bagheria, opened in 1973 in his hometown (it is housed in the Vill Cattolica building), following a donation of some of his works to the city. in Milan at the Museo del Novecento, at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Rome (here is the famous Crucifixion of 1941), and then again in Palermo, at Palazzo Steri, where one of his masterpieces, the Vucciria, is preserved. In Rome, the Accademia di San Luca also preserves works by Guttuso (the artist was an academician from 1960). The MAMbo in Bologna, on the other hand, holds I funerali di Togliatti. The two versions ofOccupation of Fallow Lands in Sicily are kept abroad, the first in Budapest at the National Museum of Fine Arts, the second in Dresden.

|

| Renato Guttuso, biography and works between art and politics |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.