Renato Mambor (Rome, 1936 - 2014) was a painter, sculptor, photographer, actor and theater director, among the biggest names inavant-garde and experimental art in Italy since the late 1950s and particularly in the 1960s and 1970s. Born and raised in Rome, he had the good fortune to be in a very lively cultural period in the city: in fact, he was part of the so-called Scuola di Piazza del Popolo.

Mambor’s research focused on the ’cancellation of individualism, finding in the stylized human figure the main element on which to build both his art and a universal and conventional language, accessible to anyone without giving rise to particular interpretations.

He was a very prolific artist, animated by a sense of urgency in creating his works; moreover, he was one of the first Italian artists of the period to not limit himself only to painting, but also to try his hand at other expressive languages, from visual ones such as film and photography to conceptual ones such as theater, sculpture and performance.

Renato Mambor, born in Rome on December 4, 1936, was the son of a gas station attendant in the Tuscolano neighborhood, an experience that probably inspired him to produce his first artworks on the theme of road signs. From a young age Mambor formed friendships in the artistic and cultural fields, very well known in fact is his association with Mario Schifano, Tano Festa, Jannis Kounellis and others, with whom he formed a collective known as Scuola di Piazza del Popolo, from the square where they used to meet. Mambor initially started with painting and then became one of the first avant-garde artists to cross over into other arts, such as photography, sculpture, film, performance, installations, and theater.

He had shown his pictorial works for the first time in 1958, at an award ceremony, receiving mixed reactions for some elements he deemed too avant-garde, even from his own friends. He organized his first public exhibition in 1959, at the gallery L’Appia antica, and thereafter frequently exhibited his work in the famous gallery La Tartaruga during the 1960s. Also in the 1960s he began experimenting first in photography and then in film. He took part with a small role in Federico Fellini’s film La dolce vita , and during his acting career he worked with Ugo Tognazzi, Walter Chiari, Totò, Chet Baker, and Damiano Damiani. Also in film, he met and became romantically linked for a long time with actress Paola Pitagora.

In 1966 he moved, together with Mario Ceroli, to the United States, where he stayed for a time to study and see Andy Warhol’s Pop Art up close. Of this current, however, he disliked the “loud” and colorful tone of the images.

In the 1970s he moved to Milan and worked extensively in theater, creating and directing a theater company named “Trousse.” The title coincided with that of one of his metal works, but used in theater it became an exemplification of his intent to provide a “tool case,” conventionally called just trousse, in order to investigate the deeper cognitive, emotional, nervous aspects of man, placed in a group context. He devoted himself to theater until 1987, and during these years he met a girl who became first his collaborator and later his wife, Patrizia Speciale.

He returned again to painting, also becoming a pioneer in this compared to his colleagues, after about ten years. Probably, this need was worked out as a result of some heart problems, which led him to consider focusing on what he thought was really important.

As soon as he resumed painting, he continued to work and exhibit his paintings until his last days. He died at his home in Rome on December 6, 2014.

Mambor’s art presents as the focal point of his reflection the removal from figures and everyday objects of all the characteristics that make them personal and individual, in search of their intrinsic objectivity. In the 1960s, Mambor used to travel around the city of Rome by various means (motorcycles, streetcars or by hitchhiking), trying to capture any situation or episode that such a culturally vibrant city at the time could offer him, then transposing these sensations into his art. In this way, he adhered to the precepts of the situationists.

His earliest works, dated 1961, were based on the ’observation of street signs, a theme derived from his experience as a helper at his father’s gas station. He used flat surfaces to elaborate objective abstract signs, tending to be geometric and flat, which by this very nature could be universally deciphered and become informational media. Mambor himself stated that “the first studies arose from observing the oblique stripes placed behind trucks.”

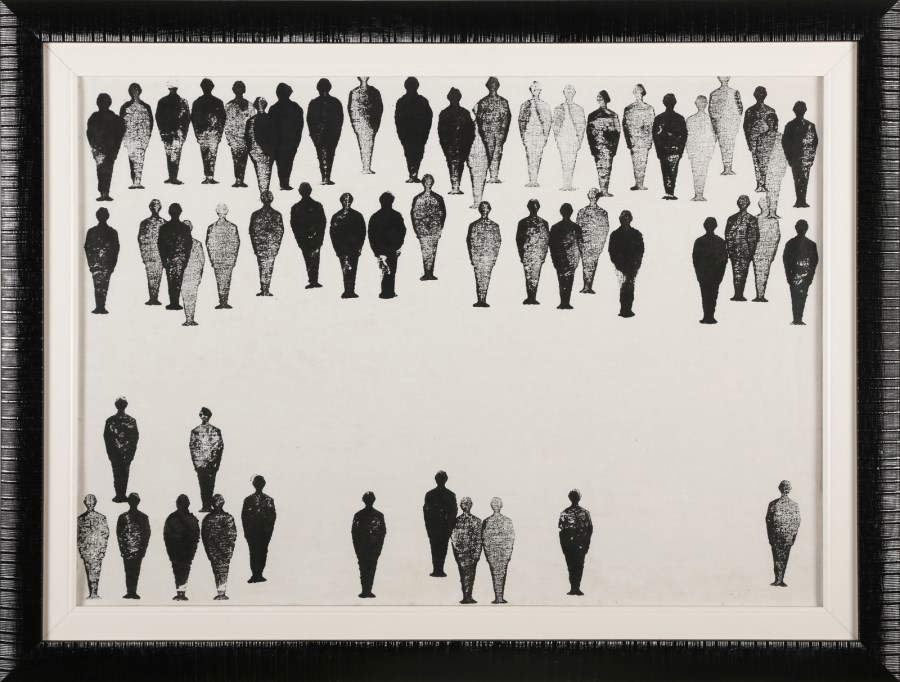

Among the road signs that had most impressed Mambor he recalled the stylized cairns of the pedestrian crossing signal. Mambor used this conventional sign to make the series of Statistical Men (1962) finding an initial mode of reflection on the ’resetting of man’s individuality and the removal of his personal characteristics, objectifying him.

Mambor’s operation, for another, captured the social changes taking place at the time, due to the growing importance of communication in people’s working and daily lives. He was trying to make communication something universal, giving birth to a metalanguage made up of “already reproduced images” (from one of his definitions), such as precisely road signs, that were decidedly inclusive in their way of being irrefutable and giving no rise to any doubt or interpretation. Later, in 1998, he described them this way, “When I invented the statistical, flat, two-dimensional man in 1962 and transposed the white silhouette as a figure of a man onto canvas, I was looking for an anemotive, inexpressive foundation that would get out of the way of the encumbrance of conformity from the outside that accumulates on the individual. Interestingly, this halo of anexpressiveness that I give to my paintings creates a fascination in the audience, as if the more you take away from the painting the more you charge the viewer.”

He resumed the subject of the stylized little man in 1963 with the Stamps series, endlessly replicating the image with a rubber stamp. The intent of this series was to certify that the work was handmade, handcrafted. The stamp was also reminiscent of the works of Piero Manzoni, who had created a performance in which he imprinted his own fingerprint on some eggs eaten by the attending public, but also Yves Klein, who “stamped” the models’ bodies with his characteristic blue.

His interpretations of the objective also anticipated the concepts that would be adopted by the Arte Povera group, under the banner of minimalism and the recovery of discarded materials, and it is no coincidence that Mambor participated in some of their exhibitions.

In 1964, Mambor decided to take very recognizable images from various periodicals and magazines of wide circulation at the time, and use them to make works of art. In this gesture he was very close to the trends of Pop Art, the movement that had just been consecrated in Italy, especially in the Venice Biennale of the same year. He chose mainly images of common objects and foods found daily on the tables of Italians, as well as the famous rebuses from “La Settimana Enigmistica.”

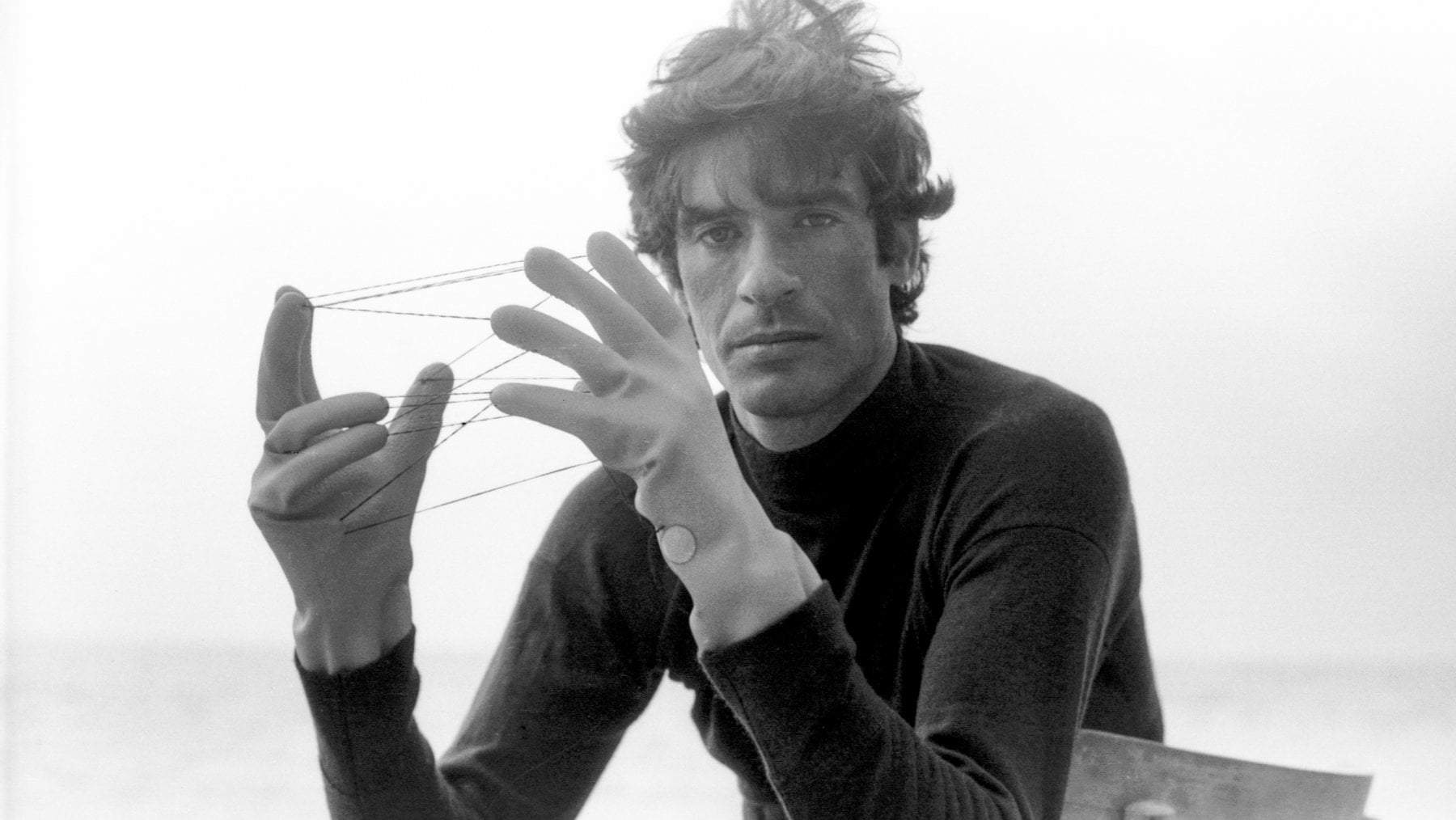

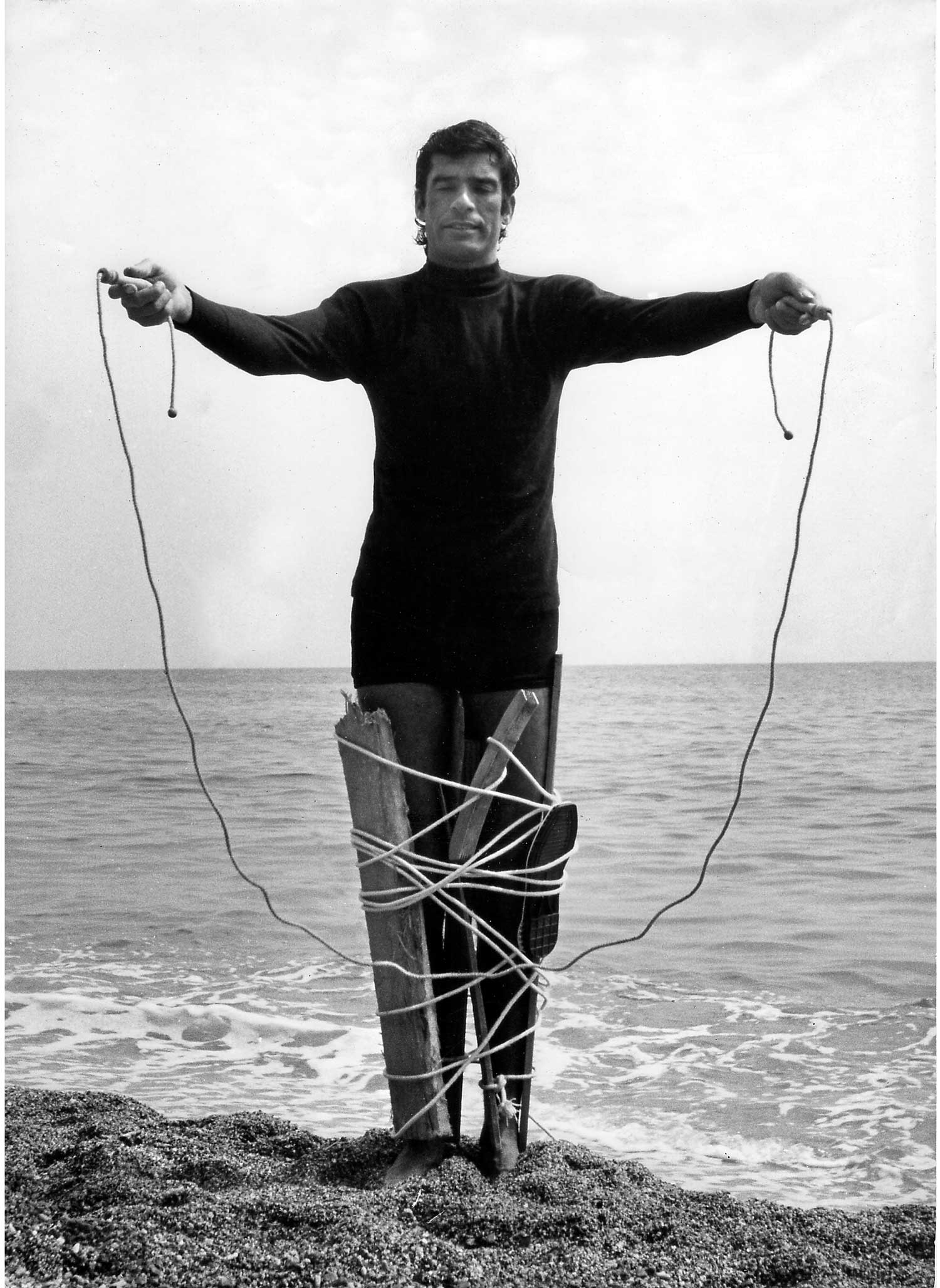

In the field of photography, in 1969 he had made shots entitled Photographed Actions, in which his body appeared to be blocked by some impediments. He then made the series Toys for Collectors, in which he included large toys in some so-called “disturbing” photographs for the Atlas of Forensic Medicine.

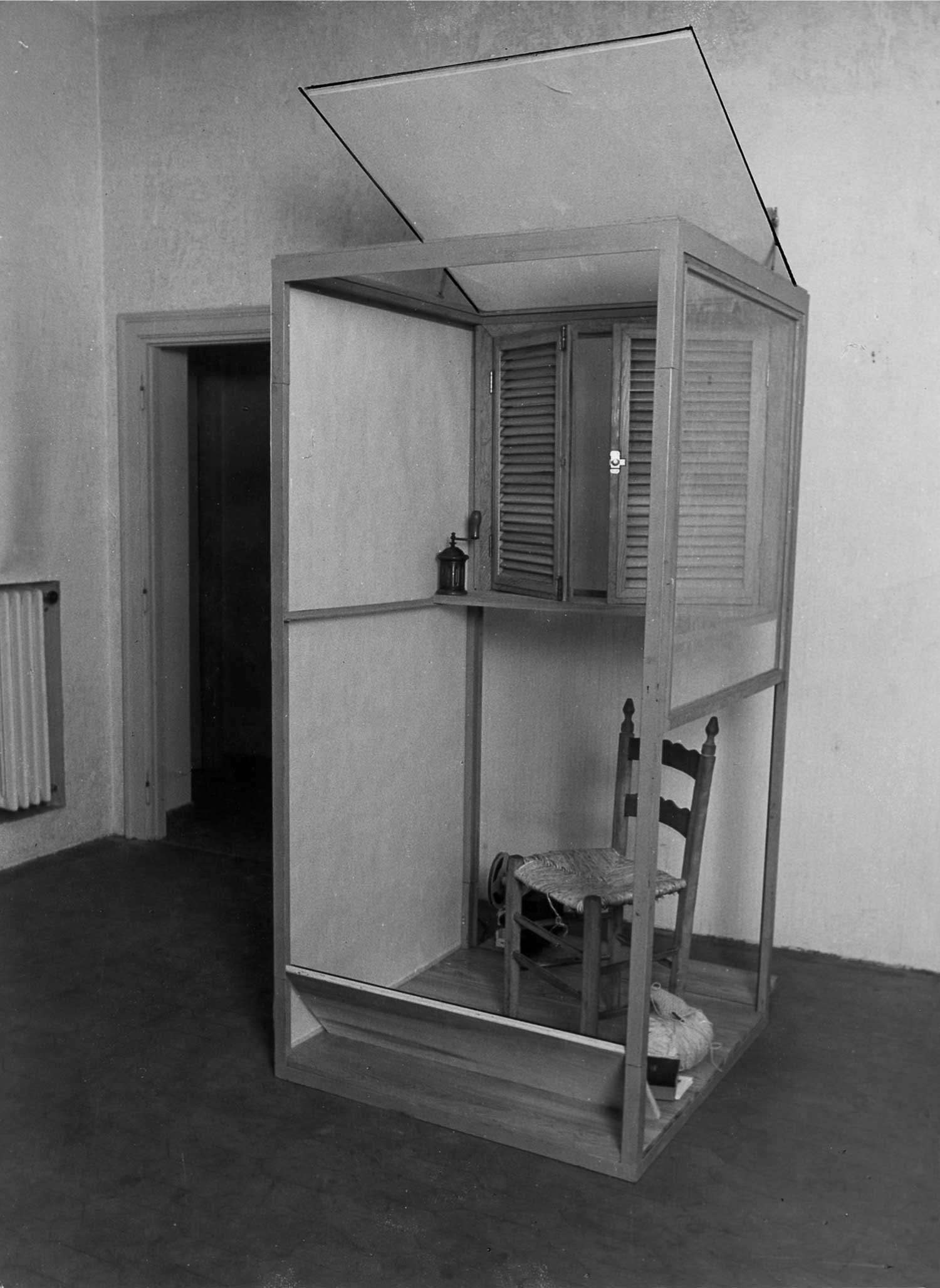

In the late 1960s, works such as Filtro (1967), Cubi mobili, Diario degli amici and Itinerari were conceived so that they could shift the value of art into that of perception, or were open works in which other artists or the public directly could intervene.

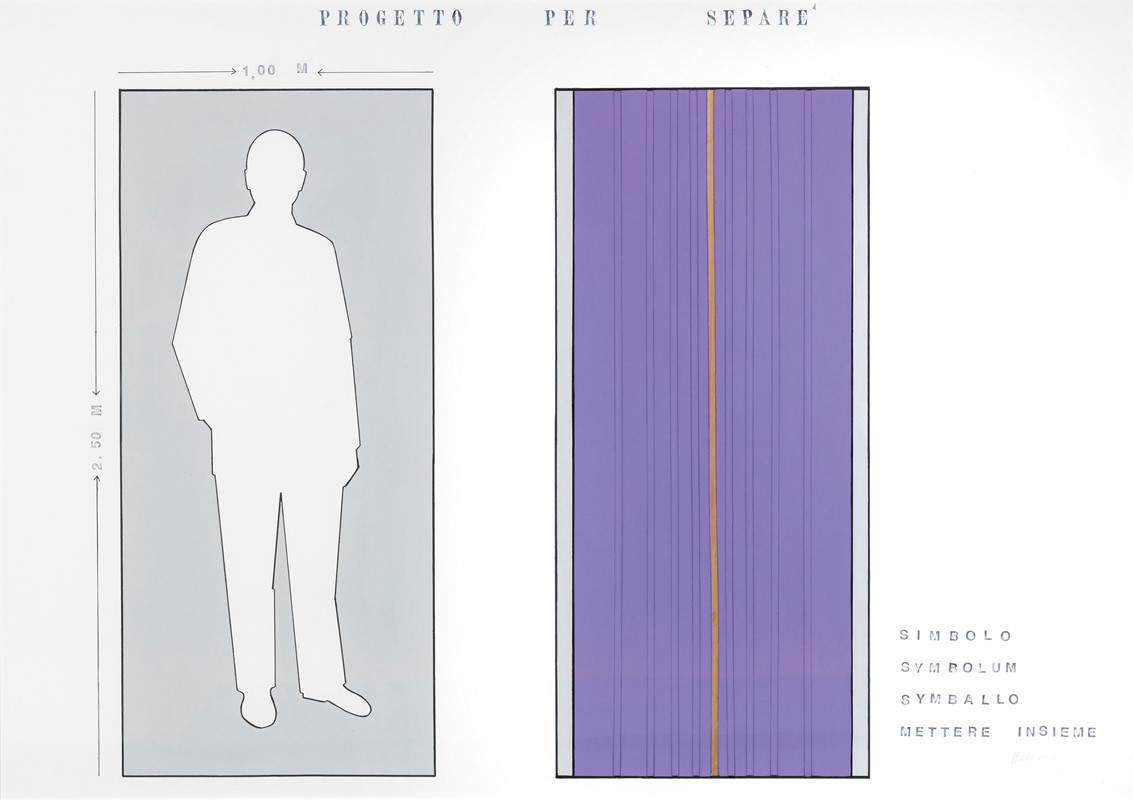

In the 1970s, Mambor conceived The Highlighter, an object that had its purpose only according to its function, and not in the creator’s intentions. It was for all intents and purposes an artifact designed and made with the help of his friend architect Paolo Scabello, and it was a device capable of highlighting particular things that are present in everyday life and that deserve to be moved into the “art category.” He also built a metal parallelepiped to which he gave the title Trousse. The trousse would later become as high as two meters and accommodate a man inside, taking on the function of a theater, again shifting the focus of research from the object to the individual.

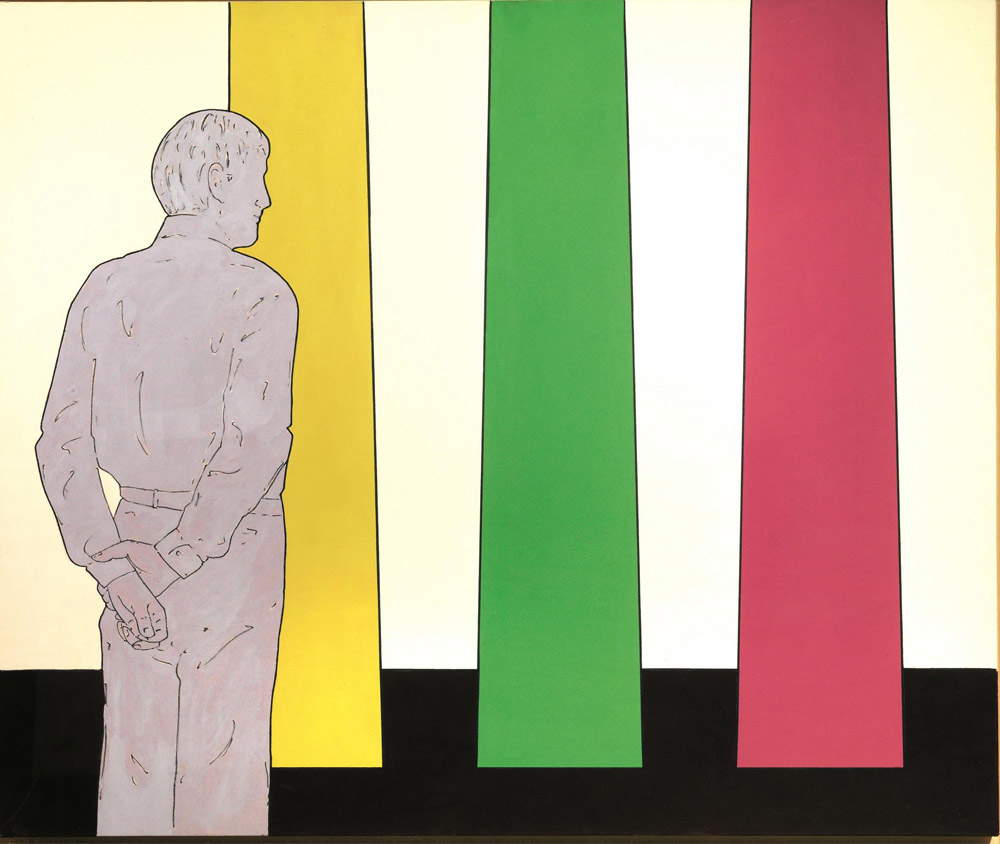

In the 1980s, Mambor returned to painting and his interest, this time, was to investigate the process that led to the creation of a given form of an object, thus abandoning the analysis of the relationship between the external form that coincides with the name of things. Regarding the return to painting, Mambor declared, “I want to do everything, dance, sing, write, act, do cinema, theater, poetry, I want to express myself by all means, but I want to do it as a painter because painting is not a way of doing but a way of being.” He included in the works of this period a drawing of his profile, cut out and placed on a window, facing some plants. This inclusion of his figure in the work, goes to symbolize an assumption of responsibility to the experience and can change point of view. Instead, it stemmed from his experience in the theater The Observer, which shows the artist from behind observing different “cultivations of painting techniques,” reasoning about the separation between the observer and the object of his observation.

The large installations continued into the 1990s, and in 1996 Mambor had the intuition to exhibit six real buses as if they were sculptures and at the same time toys, which inside them emptied house other artists; while in 1999 he set up the exhibition Doppia Coppia, in which he built motomandalas, with real vintage motorcycles.

Mambor’s art of the 2000s is very prolific and includes works such as Immutable Works, Wires, Connections, Sprints, The Concerned, The Protectors, Mandalas and Gargoyles and goes on to constitute a repertoire of figures that refer to a conceptual universe in which diversity is not understood as opposition or subordination, and as in the title of another work of the same period are All on the same plane.

He also made large installations and sculptures, which often stepped outside the boundaries of two-dimensionality. These include Separé (2007), an installation in which human silhouettes appear in different positions and attitudes on panels to which different materials are applied, creating a “pair” that keeps infinite possibilities for interaction open, since they enact none. The viewer is given the task of “completing” the work by giving the interpretation of the gold interaction. Among his most famous statements, “My work begins with me and ends in the eye of the viewer.” The same desire to bring the viewer to complete the work by adding new elements with respect to the artist is present again in Karma Immutable and Shadow Immutable, where black and white, positive and negative shadow-men silhouettes are juxtaposed to give the viewer a way to bring them back to the origin, to the matrix, the only way for there to be change.

TheMambor Archive is active in the city of Rome, which is doing a brisk job of grouping the artist’s works, often located in various private galleries and auction houses. In fact, it is often possible to see listings of Mambor’s works offered for sale.

There have been many exhibitions, both in his lifetime and posthumously, dedicated to Mambor’s works in which it has been possible to view his output. Among these exhibitions are the following set up in various museums and exhibition spaces in Rome: in 1993 Renato Mambor. The Observer and Cultivations, at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome, and Renato Mambor. The Reflector, at the Sprovieri Gallery. In 1995 Fermata d’Autobus, at Spazio Flaminio/Atac in Rome, and in 1998 Mambor. Sign work. From the ’60s to Today, at the National Institute for Graphics and in 2007 Separè, at the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome. Finally in 2009 Never buttery notes, at the Auditorium Arte in Rome.

Other important exhibitions that took place in Italy were Mambor: works from 1960 to 2000, held in 2000 at the Granelli Gallery in Livorno; in 2007 Connessioni, curated by Achille Bonito Oliva, at the Mudima Foundation in Milan; and finally in 2019 the major retrospective Mambor, at the Tornabuoni Arte Gallery in Florence. Several exhibitions dedicated to Mambor have also been held abroad, in Paris, Berlin, Prague, London and the United States.

|

| Renato Mambor, the artist of objectivity. Life, works, style |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.