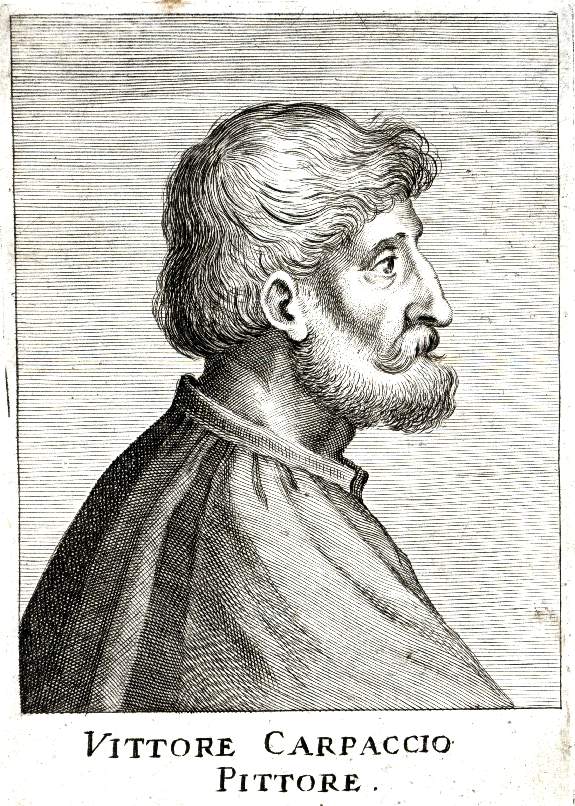

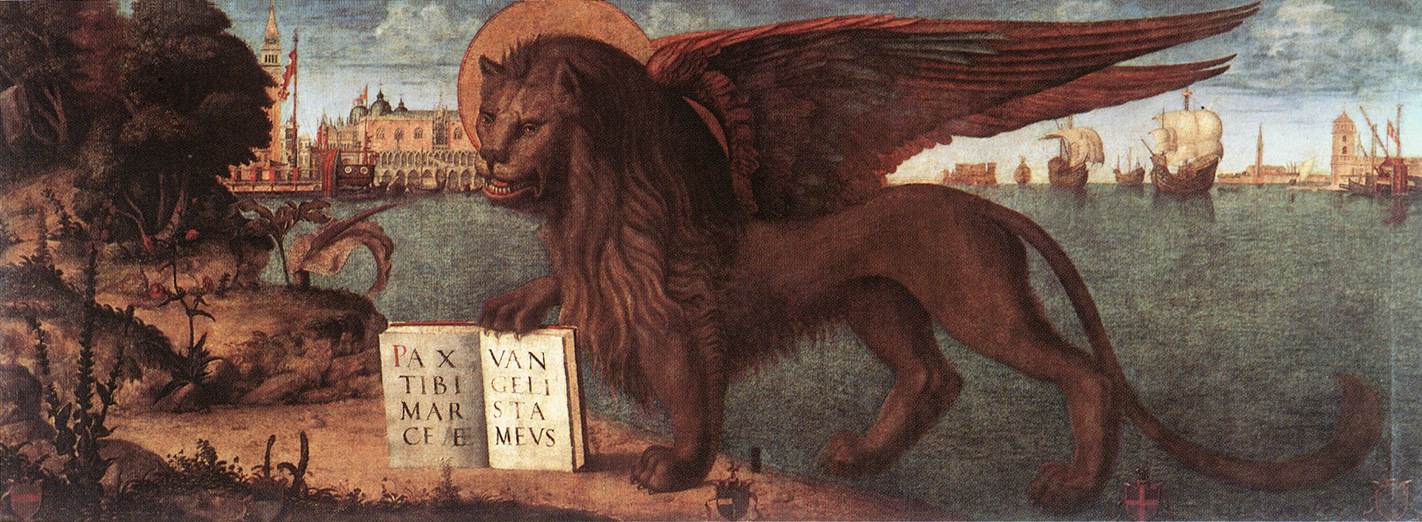

Vittore Carpaccio, sometimes also called Vittorio (Venice, c. 1465 - Koper, 1526), was one of the greatest Venetian painters of the Renaissance. Particularly attached to his city, Venice, Carpaccio became famous for his large canvases, large works on canvas that in the lagoon city, for conservation reasons, replaced frescoes (which would easily degrade due to moisture), and on which sacred stories, particularly of saints, were often depicted.

In general, Carpaccio always favored hagiographic themes, demonstrating that he possessed a vast humanistic culture, thanks to the inclusion in his works of particular quotations and the ability to insert nonrealistic elements within episodes that actually happened. Thanks to his canvases, he is also considered one of the best witnesses of the appearance of 15th-century Venice.

He was highly renowned for his tendency to devote himself in a very laborious manner to the most minute details of composition. His fortunes were fluctuating, between little success and large commissions, until a gradual decline and lowering of the level of his painting, due to his conviction that he did not want to adapt to new trends, but to remain consistent with his pictorial ways.

Vittore Carpaccio ’s life and artistic parabola are closely linked to the city of Venice. Here, the artist was born around 1465. Not many details of his life are known due to the scarcity of information from written sources, however, several facts known to us have been deduced from the analysis of the dates affixed to paintings bearing his signature. Regarding his family, the certain information concerns the name of his father, Pietro, and it is known that from an early age Carpaccio was a frequent visitor to the prestigious humanistic circles of Venice. Even as an adult, the artist gave ample evidence of his wide-ranging culture through the inclusion of researched quotations in his works. The surname “Carpaccio” (an Italianization of the signature Carpathius and Carpatio by which the artist signed himself) is actually an adaptation of “Scarpazza” or “Scarpazo,” a family originally from the island of Mazzorbo, which, however, perhaps as early as the 14th century, had moved to Venice. However, the first document about him dates back to 1472: it is the will of his uncle, Ilario, a friar of the convent of Sant’Orsola (born Giovanni Scarpazza), who designated Vittore as heir in case of a dispute between the beneficiaries of the will.

Vittore Carpaccio was one of the leading exponents of the Venetian school of painting, and it is believed that the masters who accompanied him in his artistic training and were an inspiration for his art were Gentile Bellini, Lazzaro Bastiani, Giovanni Bellini, and Antonello da Messina. To this direct contact, Carpaccio combined a good knowledge of Flemish art. Moreover, it is almost certain that he had the opportunity to see and study the works of Piero della Francesca in Ferrara. Some sources identify as his other teacher the painter Jacometto Veneziano, who was very famous and admired at the time.

Compared to the high level of attention given to other Venetian artists of his contemporaries, Carpaccio’s works have long been undervalued. However, later, his works were reevaluated and Carpaccio later began to become in demand, obtaining major commissions from the powerful Venetian Schools. For example, between 1490 and 1495 he was involved in the creation of the canvases with the Stories of St. Ur sula for the Scuola di Sant’Orsola, now in the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, and later he would be commissioned for the decorations for the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista. Again, between 1501 and 1502 he was commissioned to make a large canvass for the Sala dei Pregadi in the Doge’s Palace, and also in the early seventeenth century he obtained a commission for the cycle of canvases for the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni. He would later work for the Scuola di Santa Maria degli Albanesi (between 1504 and 1508) and for the Scuola di Santo Stefano (between 1511 and 1520). However, while Venetian painting was opening up to some renewals, Carpaccio always preferred to remain very consistent with his style and did not want to adapt to new developments, suffering a rather rapid decline over time. Gradually, in fact, commissions became more scaled down, coming mostly from small provincial churches. One of these came from the cathedral in Koper, the city where Carpaccio settled permanently and where he died in 1526.

Carpaccio proved to be one of the most cultured and intellectual artists of his time. In his works it is possible to identify elements that reveal a thorough knowledge regarding early printed books, courtly poems and novels, archaeology, works of classicism, Greek and Hebrew inscriptions, hagiography, heraldry, bestiaries and herbaria. Art critic Giulio Carlo Argan pointed out that Carpaccio’s painting, which mostly focuses on hagiographic themes, had no educational purposes to teach prayer or philosophy. On the contrary, it adhered more to the doctrine of Aristotle and empiricism, which was widespread at the time in the University of Padua.

From the beginning, Carpaccio always presented a personal style in his works, not conforming to the pictorial fashions of the period. Characteristic of his production are the teleri, large paintings on canvas that were widely used as wall decorations and were in great demand in Venice. They were often decorated with depictions of stories of saints, such as Carpaccio’s earliest known canvases with the Stories of St. Ursula (1940), made for a chapel in the Scuola dedicated to the saint and taken from Jacopo da Varazze’s Legenda aurea. Carpaccio executed a total of nine canvases, the dates of which asciano imply that he did not realize the episodes in the order of the narrative, but devoted himself to them on several occasions as soon as the walls of the building were cleared of elements of antique furniture.

It is precisely the detachment in time that makes it clear how Carpaccio had developed a very rapid maturation, going from being rather immature and in some cases clumsy, especially in the composition and perspective of the scenes, which often lack narrative focus, to presenting fine solutions, great confidence in the composition of landscapes and deep views. The portrayed characters are never depicted with particular emotional expressions, but seem almost suspended in a timeless limbo. Light is used to emphasize very minute details of architecture and clothing. In general, Carpaccio was a very skilled painter in rendering details, to which he gave great importance by applying himself to them with great dedication. Moreover, through the scenes of the saint being kidnapped and then brutally murdered in Cologne by a horde of Huns, suffering the same fate as the virgins who had accompanied her on her journey to meet her betrothed in Rome, it is possible to read a clear allegory of the affairs of Venice, engaged at that time in a clash against the Turks.

The canvases of St. Ursula secured Carpaccio other commissions, such as other canvases for the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista and the Miracle of the Cross at Rialto (1496), in which the miracle is placed on the left of the canvas, and the rest of the space is devoted to a depiction of Venice full of life, constituting one of the instances in which the view of the city lagoon will reach such a high level that it will hold the record for a long time, until the arrival of Canaletto. Carpaccio wanted to depict the city of Venice at its moment of greatest splendor and wealth, with a twofold objective: to emphasize the great civic pride retained by the Venetians, and to echo the ideological and political positions of his patrons, who thus recognized in Carpaccio an obvious tendency to play the role of propaganda painter.

Carpaccio often allowed himself to include certain licenses in his works, such as the depiction of buildings that did not exist in reality, or the presence of highly multicolored clothing and headdresses and animals of exotic taste, giving the scenes a fable-like character, which, however, never blurs into the fantastic, as it still represents events that actually happened.

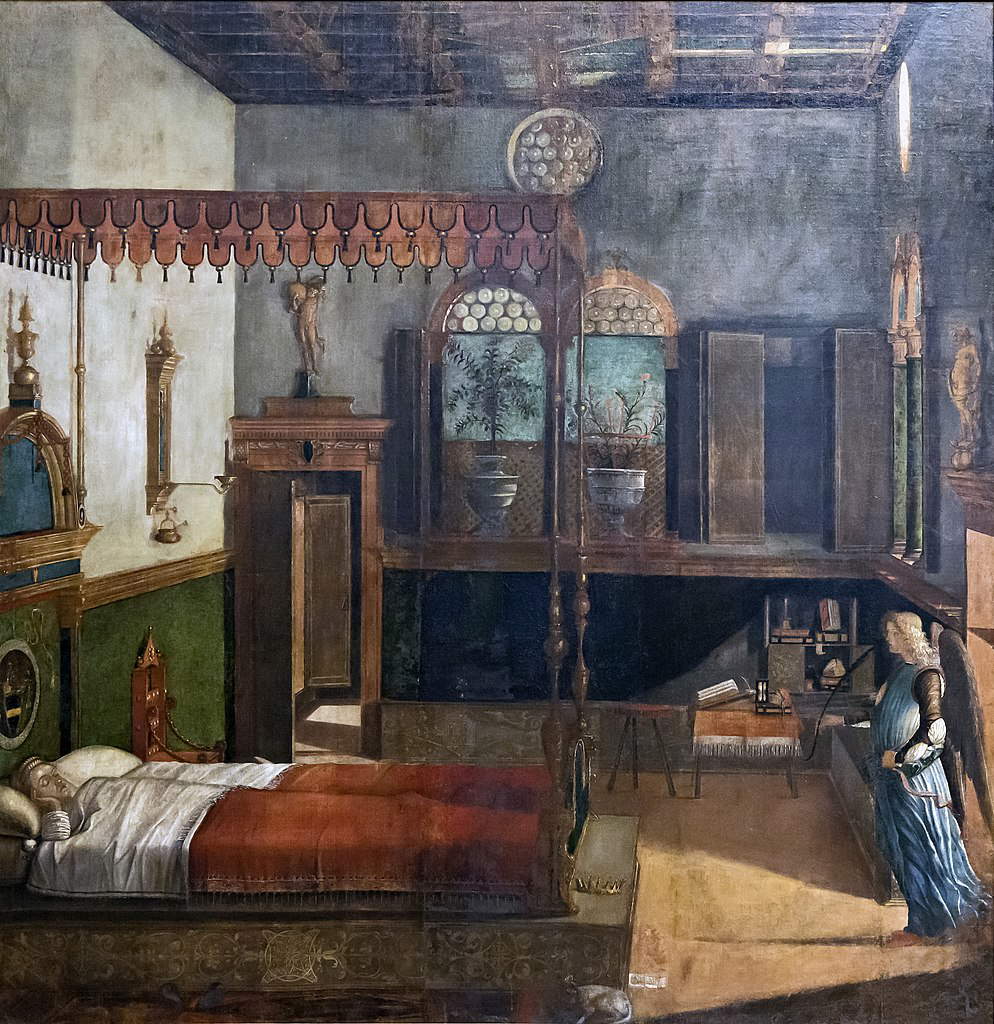

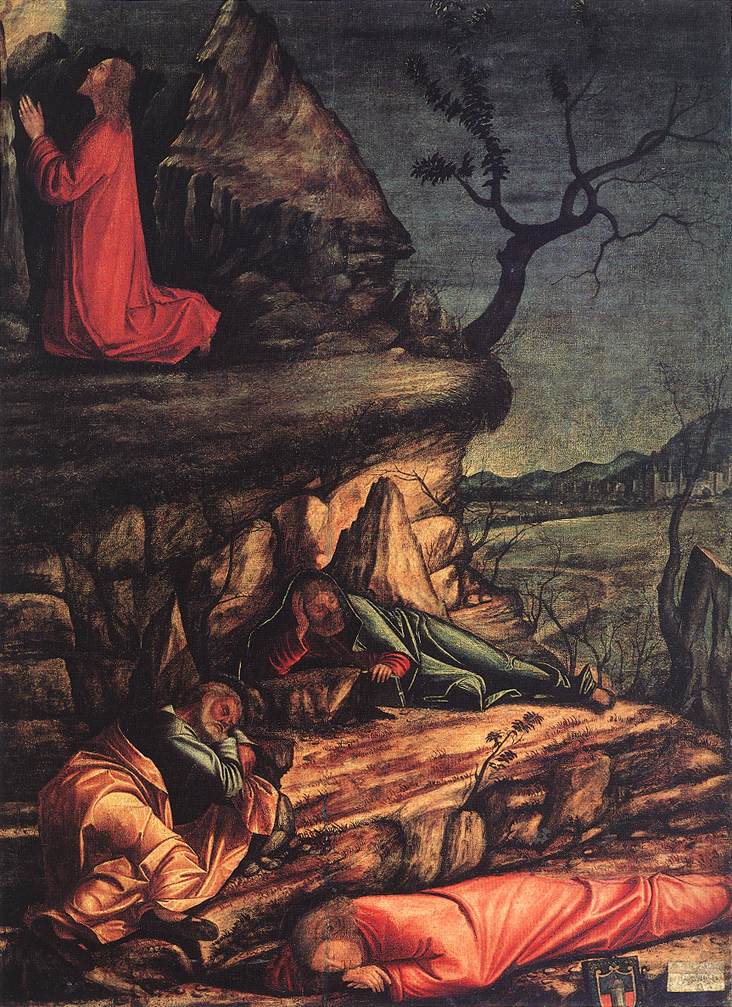

Between 1502 and 1507, Carpaccio was engaged in making several canvases with the Stories of St. George, for the School of San Giorgio degli Schiavoni. Unlike the School of St. Ursula’s teleri, in which several episodes were depicted in each story, in these Carpaccio devoted himself to single episodes, the highlight of which is St. George slays the dragon. The famous scene is set in a landscape with an exotic feel, thus enhancing the figure of the hero who has come from afar to resolve the dangerous situation and restore the world to order. In addition to the stories of St. George, the canvases made for the school also feature other hagiographic episodes, including episodes from the lives of St. Jerome and St. Tryphon, and two important scenes from the Gospels such as the Vocation of St. Matthew and the Prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane. The two scenes of St. Matthew were chosen to indicate the School’s veneration of the saint after one of his relics was given to him.

In this cycle, the presence of fantastical and imaginary elements is accentuated, which are skillfully blended with the more realistic details so that the scene is nonetheless believable.

In the last canvases, dated 1507, Carpaccio betrays a certain repetitiveness in some solutions and an impoverishment of color. Probably at this time he had begun to surround himself with collaborators who intervened on his commissions.

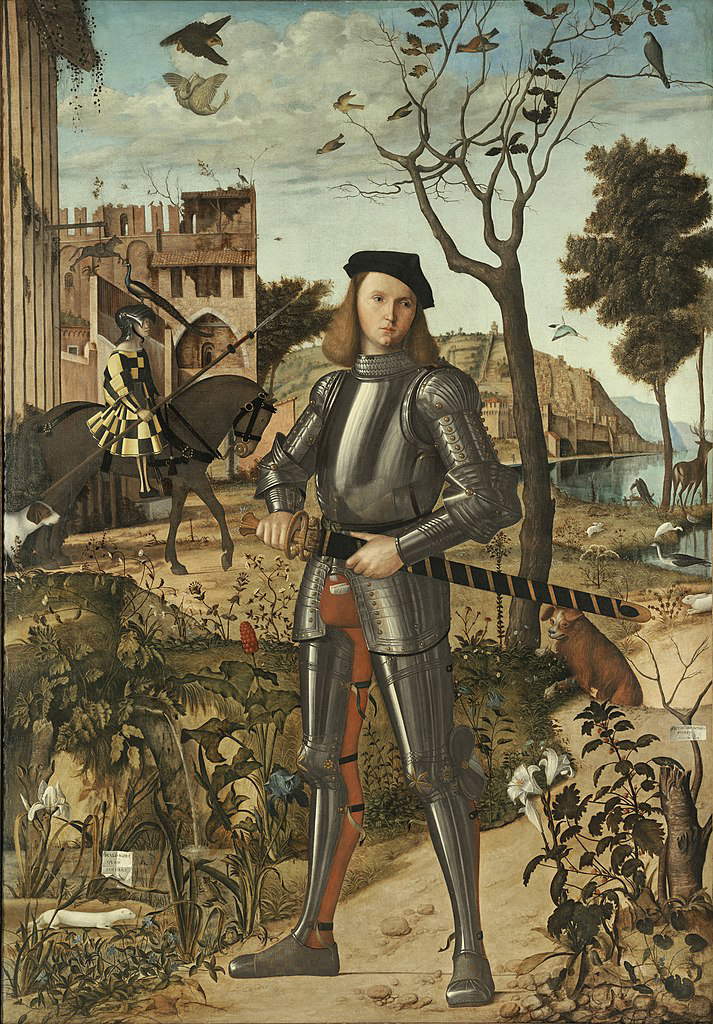

Dated 1510 is the work Portrait of a Knight embellished with incisive graphic definition. Also included in his output are the altarpieces with Saint Peter Martyr in Murano and the one for Santa Maria in Vado in Ferrara, testifying to a well-established reputation, which thus enabled him to obtain commissions outside Venice and for important Italian provinces.

Over the years, Carpaccio, did not want to adapt to contemporary innovations and trends. In fact, while the innovations in the use of color brought by Giorgione, Titian, and Sebastiano del Piombo rose to prominence, and there was news of the great works of Raphael and Michelangelo, Carpaccio’s style by comparison was becoming increasingly antiquated. He himself found himself bewildered when in contact with the new artists: in fact, there is a story of an episode in which he was called upon to evaluate some frescoes by Giorgione in order to decide on the fee to be attributed to the artist, finding himself in front of works radically different from his own. Carpaccio thus remained isolated, a factor that conditioned his later works, which were not at the same level as his earlier ones. An example of this is the cycle of the Stories of the Virgin executed between 1504 and 1508 for the confraternity of the Albanians, as well as the Stories of St. Stephen (1511-14), in which a certain repetition of models and patterns inferred from earlier works was evident. Carpaccio’s entire last productive phase saw him working laboriously, obtaining commissions for small provincial churches to which he devoted himself, always remaining faithful to his style, which nevertheless further lost quality.

Carpaccio’s last known works include a Dead Christ (1520), in which the atmosphere takes on decidedly alienating and surreal tones due to the inclusion of numerous symbols of death, an indicator of a personal reflection on human mortality. Finally, mention should be made of the altarpiece and organ doors of the cathedral in Koper, where he had settled in the last years of his life.

Vittore

Vittore Vittore

Vittore Vittore

Vittore Vittore

VittoreMost of Carpaccio’s best works remained in Venice, his hometown, precisely because of a fluctuating interest in him compared to the fortune enjoyed by other Venetians of his time. Still in Venice are the Stories of St. Ursula(1490-1495) , the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple (1491-1510) and the Miracle of the Relic of the Cross at Rialto (1496) in the Gallerie dell’Accademia, and the Two Venetian Ladies (c. 1490-1495) in the Museo Correr. Also of note are the other two cycles of canvases, the Stories of Saints Jerome, George, Tryphon and Matthew (1502-1507) in the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni and some scenes from the dismembered Stories of the Virgin, namely theAnnunciation at the Franchetti Gallery of the Ca’ d’Oro, the Visitation at the Correr Museum, on deposit at the Franchetti Gallery of the Ca’ d’Oro, and the Death of the Virgin in the Franchetti Gallery of the Ca’ d’Oro.

A number of Carpaccio’s works are held at important Italian museums, such as the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple (1505) and the Miracle of the Flowering Rod or Marriage of the Virgin (1505) from the Stories of the Virgin and Dispute of Saint Stephen, in the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan; Halberdiers and Elders (c. 1490-1493) at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence; and Portrait of a Lady (c. 1495-1498) at the Galleria Borghese in Rome.

In Europe, works by Carpaccio can be seen at the Louvre in Paris, where the Preaching of St. Stephen (1514) from the Stories of St. Stephen is kept, and at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin is St. Stephen and Six of His Companions Consecrated Deacons by St. Peter (1511), also from the Stories of St. Stephen, and then again the Dead Christ (1520).

In the United States, there are preserved, in chronological order, Hunting in the Lagoon (c. 1490-1495) at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles; Escape to Egypt (c. 1500-1510), Reading Madonna (1505), Blessing Madonna and Child (1505-1510) at the National Gallery of Art in Washington; and finally Meditation on the Passion (c. 1500-1510), at the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

|

| Vittore Carpaccio, protagonist of 15th-century Venice. Life, works, style |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.