Is the Mona Lisa, Leonardo da Vinci ’s masterpiece preserved in the Louvre, the second version of a painting that the great Tuscan artist had begun earlier? This is the question posed by Salvatore Lorusso in his book Is the Louvre Mona Lisa Leonardo’s second version?, recently released by L’Erma di Bretschneider Editions (136 pages, 75 euros, ISBN 9788891325839). Lorusso, a former professor of Chemistry of the Environment and Cultural Heritage at the University of Bologna and founder, at the same university, of the Laboratory of Diagnostics for Cultural Heritage, returns to a problem that has often been discussed by Leonardo scholars (Carlo Pedretti, for example, already talked about it in the 1950s) to take stock of the situation, with the aim of finding the square and reaching a conclusion. Which we can immediately anticipate: for Lorusso, in fact, the “significant evidence presented in each of the chapters of this volume,” we read in the book in English (the translation is ours), “should establish beyond reasonable doubt that Leonardo executed two distinct Mona Lisas in different periods, and confirm their individual characteristics: an early, unfinished Mona Lisa, and a later, finished one that is stylistically and structurally different from the earlier one.” This later, finished one would be, according to Lorusso, the work we can all see in the Louvre today.

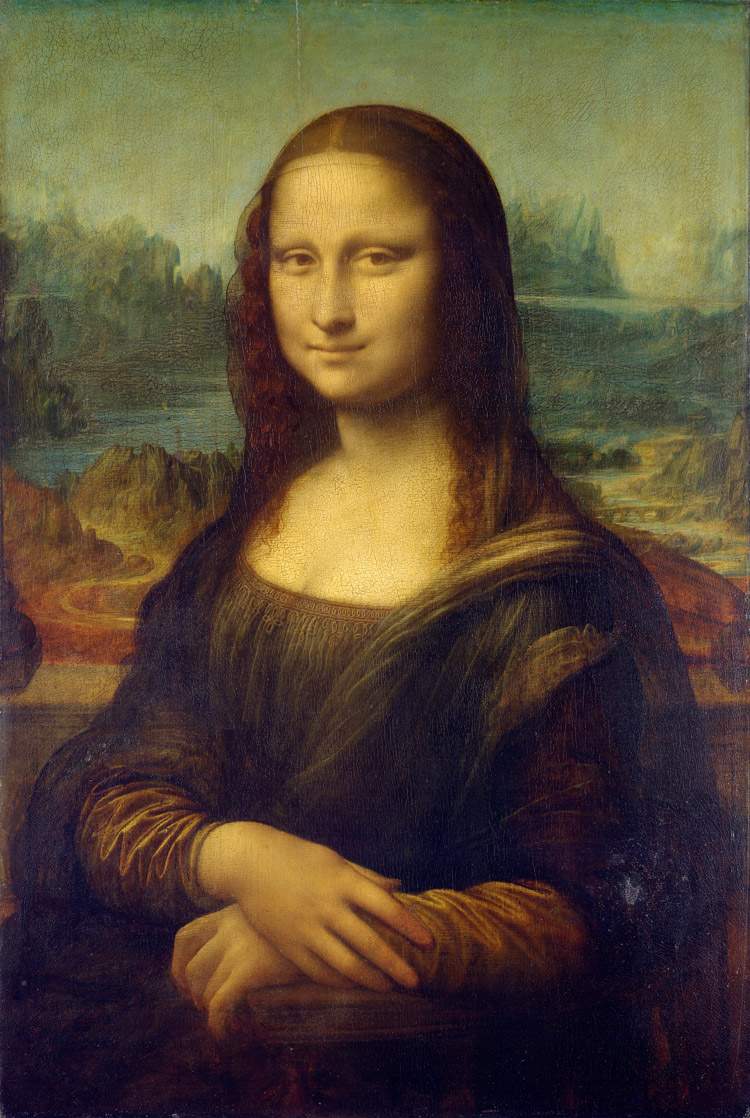

There are at least seven pieces of evidence, according to the author, to support this thesis. The first is the description of the Mona Lisa contained in Giorgio Vasari’s Lives: the great historiographer, in both editions of his monumental work (the one of 1550 and the one of 1568), describes the painting in detail, stating that Leonardo left it unfinished, and asserts that it was commissioned by Francesco del Giocondo, husband of Lisa del Giocondo, or the “Mona Lisa” of the painting. One finds here the first contradictions, according to Lorusso, since Vasari speaks of an unfinished work, while instead the Mona Lisa in the Louvre is a finished painting, and furthermore Vasari does not mention the landscape, which is present in the painting instead. It must be remembered that Vasari never saw the work and therefore necessarily relied on reported information, but according to Lorusso it must also be admitted that the observer who described the painting to him must have seen it. The second piece of evidence is considered to be the discovery in 2005 of the "Heidelberg document," a note, found at the German university library by scholar Armin Schlechter, in which an assistant to Niccolò Machiavelli, Agostino Vespucci, refers to a “head of Lisa del Giocondo” in 1503, calling it a “pictura” and making a comparison with the ancient painter Apelles, a circumstance that in 2008 had led Vincent Delieuvin, a Leonardo specialist, curator of the Louvre and curator of the major exhibition on Leonardo held in 2019 at the French museum, to say during a television broadcast that “we cannot be absolutely certain that this portrait is the painting in the Louvre.”

The third clue is the famous pen-and-ink drawing by Raphael Sanzio, circa 1504, which depicts a woman, in the same pose as the Mona Lisa, with, behind her, a barely noticeable background but where we can clearly distinguish the two columns that Leonardo evidently planned to include in the painting and which we find again punctually in several late copies. Raphael depicts a very young woman, or at any rate younger than the Mona Lisa in the Louvre. These are all signs that the Urbinate would have been looking at a different work, according to Lorusso: specifically, at a painting executed by Leonardo between 1503 and 1506, where the figure of the younger Mona Lisa (Lisa del Giocondo was born in 1479) was seen above a sketched landscape, and framed by two large columns on either side. The fourth item is the travel diary of Antonio de Beatis, secretary to Cardinal Louis of Aragon, who visited Leonardo in Amboise in 1517. In the diary, De Beatis notes that among the paintings observed by him and the cardinal at Leonardo’s residence, the chateau of Clos-Lucé, were three paintings including a portrait of “certa dona fiorentina facta di naturale ad istantia del quondam magnifico Juliano de’ Medici.” We do not know for certain what the painting in question is, but many believe it to be the Mona Lisa in the Louvre, which was in France at the time: the note actually raised much discussion, and Lorusso’s position is that it refers to a different painting than the one Leonardo had begun in 1503, and that its commissioner was Giuliano di Lorenzo de’ Medici, duke of Nemours.

Continuing, the fifth element is the style of the painting, which is compatible with the mature phase of Leonardo da Vinci’s art. Moreover, the morphological characteristics of the landscape would be compatible with some drawings dating from the period 1513-1516. The sixth element, on the other hand, is given by the Mona Lisa of the Prado, a work by another artist inspired by the Leonardo prototype, which, according to Lorusso, makes it possible to fix the dating of the Mona Lisa of the Louvre to 1513-1516, since the Spanish variant is believed to be contemporary with the Mona Lisa and its author, hitherto unknown, had to see the master at work until the final touches on the Louvre painting in order to create such a likeness: a circumstance that, according to Lorusso, given also the results of the analysis from which it emerges that the Prado variant followed the development of the Louvre original in its execution, would allow the idea of a long gestation of the painting to be discarded. Then there is the seventh element, which Lorusso considers decisive: the results achieved by the analyses on the Mona Lisa carried out between 2004 and 2005 by the Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France (C2RMF). In particular, the examinations revealed that the balustrade with the columns was painted over the figure, that the portrait was painted directly over the preparation, that there is no evidence of drawings or transfers from cardboard, that the background and figure appear to have been painted simultaneously, that the preparation runs all the way around the panel and thus the work was not cut, and that the pattern of the craquelure indicates that the landscape was all painted at the same time. That being the case, Lorusso says, it is not possible that the Mona Lisa is the work Vasari and Vespucci talk about and that Raphael drew, because Leonardo would not have added the landscape later, and then the Louvre Mona Lisa would not have originally had columns then cut later, the existence of a preparatory cartoon would be unlikely, and the Louvre Mona Lisa would be an accomplished painting. C2RMF analysis would also have clarified the stages of the painting’s realization, summarized by Lorusso as follows: first, Leonardo painted the background and balustrade; immediately after, he executed the figure of Mona Lisa along with everything else; third, he painted the woman’s veil, making it over the background; finally, he added the columns. “This sequence of events,” the author writes, “is of primary importance because it rules out the possibility that this is the same portrait that Raphael saw and sketched in 1504. This is because [...] the portrait he saw included the woman with her veil, as well as the columns beside her, but not the background.”

Lorusso then includes other elements, less decisive, but still worthy of attention: for example, a passage in Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo’s Trattato dell’Arte della Pittura where it is said that Leonardo executed “the portrait of the Mona Lisa et of Mona Lisa,” or again the fact that there are more than one autograph version of some of Leonardo’s works (this is the case with the Virgin of the Rocks), and again the documents of Salaì, namely, an inventory of the works in his possession in 1525, which also mentions a portrait of a woman “dicta la Joconda,” with a very high valuation, and a 1518 receipt concerning the sale of many paintings to Francis I of France, among which it is perhaps possible to include the Mona Lisa in the Louvre. However, in a later listing of the same paintings in Salì’s possession in 1525, compiled in 1531, and stating that his sister had given them to a certain Ambrogio da Vimercate as a pledge for a debt, the valuation is much lowered, an indication that they were probably not originals by Leonardo. Other hypotheses instead want the Mona Lisa, for some time, to have returned to Milan. In short, the case of the two documents is rather thorny.

What is the Louvre’s position in the debate? On the file of the painting, compiled by Vincent Delieuvin in 2021, a dating 1503-1519 is proposed and some of the points raised by Lorusso are discussed. On De Beatis’s document that the Mona Lisa was allegedly painted for Giuliano, Duke of Nemours, Delieuvin recalls that Leonardo often demonstrated unparalleled freedom with regard to his obligations to patrons: some works, the museum argues, were begun and left unfinished (such as theAdoration of the Magi now in the Uffizi), or given to others (the first version of the Virgin of the Rocks). In support of this idea, the Louvre cites a letter written by Leonardo da Vinci to Charles II d’Amboise, governor of Milan at the time of the French occupation, in which the artist wrote that he had brought from Florence to Milan two Madonnas of different sizes “which I have begun for the most Christian King or for whomever you like,” an indication that Leonardo did not find it strange to begin a painting for one client and finish it for another. For the Louvre, in essence, Leonardo had to work slowly, “gradually creating a marvelous masterpiece that seduced successive patrons, Louis XII, Giuliano de’ Medici and finally Francis I who came to acquire it.” Moreover, on the painting’s incompleteness, the Louvre itself in the file reports that Leonardo began the painting around 1503 and kept it “until the end of his life to continue the execution, still unfinished at his death.” There are elements that are indeed unfinished: “the two half-columns visible on either side of the lady,” as Pietro Marani has written, “the parapet and part of the landscape on the left, where the reddish color of the preparation appears, just as the fingers of the left hand, of which variants are glimpsed in the more or less bent position, seem unfinished. Even the index finger of the right hand shows a visible repentance in its width and design.” Marani, in citing the 1954 X-ray, the first performed on the painting, states that different was initially the hypostation of the face, which was then changed over time with subtle glazes of oil color. Will the evidence indicated by Lorusso be enough to change the Louvre’s mind?

|

| Is the Mona Lisa in the Louvre the second version of Leonardo da Vinci's work? |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.