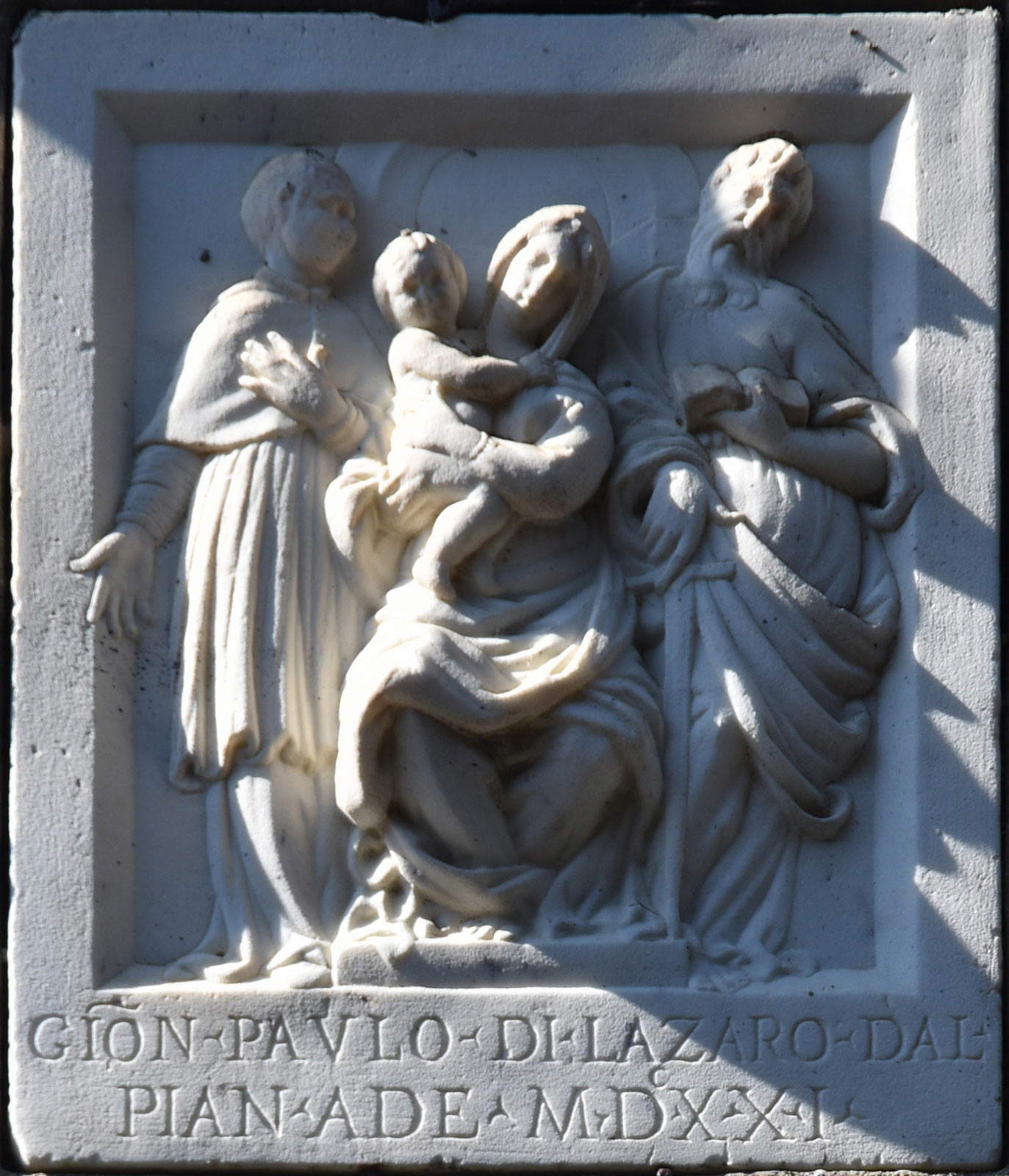

Who were the sculptors who carved the majesties, the votive reliefs that abound on the ancient roads of the Apuan Alps? This is the question that the book I maestri delle maestà aims to answer. Protagonists and Components, published by GD Editions (67 pages, 20 euros, ISBN 9791280745064). Anyone who has visited Lunigiana, Val di Magra or historic Versilia has surely encountered, in an alley of a village, on a mule track or on a mountain road, a maestà: these were small devotional bas-reliefs, made of marble, which were always placed on exterior walls and which were very popular at least from the second half of the sixteenth century, after the end of the Council of Trent. Majesties were indeed meant to inspire faith and devotion in those who observed them. The phenomenon lasted until at least the mid-20th century.

Long studied, the subject of numerous in-depth studies, they remained mostly anonymous, and there were no past attempts to reconstruct the identity of their authors. Before arriving at GD Edizioni’s book, however, it was necessary to carry out a massive work of cataloguing on the initiative of the CAI of Sarzana, which availed itself of the scientific advice of art historian Piero Donati, one of the leading experts on the subject: the project, entitled The Majesties of Historical Lunigiana, as of March 15, 2022, has already surveyed more than three thousand majesties (most concentrated in the territory of Fivizzano, where there are currently 421 majesties, and Carrara, where 340 have been catalogued), all of which can be consulted, with good photographs, cards, technical data and geolocation on the website www. lemaesta.it.

“This tracing,” explains the working group composed of Pete Avenell, Franca Bologna, Liliana Bonavita, Luciano Callegari, Luciana Corsi, Fabrizio Franco and Nello Lombardi, “protects the good by bringing it out of anonymity, giving it geographical and historical identity and a condition of recognizability which we hope, on the one hand, will stimulate the institutions to a work of protection and restoration, and on the other, in case of theft, will make it identifiable to the deputized law enforcement agencies and allow the prosecution of its subtraction when, for example, the plate should reappear on the antiques market.” A significant scientific project that has made it possible to significantly enhance this very important historical and artistic heritage, and has stimulated the initiation of further studies and investigations, of which The Masters of Majesties. Protagonists and co-protagonists is one of the most up-to-date results: in fact, without the work of filing it would not have been possible to proceed with comparisons by “families” of majesties and thus identify their authors.

The study was taken up by Piero Donati himself, who saw clear kinship links between several majesties, resulting from the stylistic analysis of these marble reliefs. The scholar identifies some important premises from which to start: first of all, it is necessary to consider majesty first and foremost as sculptural products, which spread mostly in the middle strata of society, convinced that marble was the most valuable material and therefore was a kind of status symbol, a circumstance that contributed to providing a lot of work for the workshops of the masters who carved the majesties. Moreover, these were widespread products, which on the back of a mule could reach vast areas: majesties are attested not only in Lunigiana and historic Versilia, but also in Garfagnana, beyond the Apennines to Castelnovo ne’ Monti, Borgo val di Taro and the mountains of Parma, and westward in the Val di Vara, even as far as Sestri Levante. And then, the fact remains that there is a lack of written attestations about the majesty, except of course for the inscriptions that often accompany them. So, the fact that there are no written sources forces one to attempt to identify the authors of majesty on stylistic grounds alone. More importantly, for the vast majority of the authors it is not possible to trace a first and last name: it is therefore necessary to identify them with namepiece formulas.

Donati traces the origins of the majesties to some fifteenth-century votive reliefs found in the villages on the mountains of Carrara: we start in 1466, the year in which a sculptor, Pietro di Guido da Torano, signed a San Bernardino whose manner would be taken up by a “Master of Miseglia” responsible, according to Donati, for seven slabs found between Carrara and Fivizzano, which can obviously be approached on stylistic grounds. However, these are sporadic episodes: it will be necessary to wait until the end of the Council of Trent to see a rapid spread of majesties: the strong growth of these works is in fact recorded from the end of the sixteenth century, and these are works that reach a quality not even comparable to that of the reliefs of the Master of Miseglia, precisely because in the sixteenth century there is an important qualitative leap in commissioning (“more informed and more demanding,” writes Donati), and consequently in the work of the masters.

In the first decades of the seventeenth century a real majesty industry was born, with what serial productions entailed: works of lesser quality, but the possibility of tracing the places where the masters worked and their workshops. The first master to whom it is possible to give a precise physiognomy is what Donati calls the "Master of the Madonnas on Thrones, " who appears to have been active in 1626 and to whom reliefs found in Massa, Avenza, Fivizzano, Monchio delle Corti and Licciana Nardi are attributed. This is an interesting author, whose formulas were spread and taken up by other artists more awkward than him and who can therefore be reasonably identified as his followers. On the other hand, the affair of the "Master of 1659,“ so identified by a majesty present in Castelnuovo Magra, where this date is written, is placed after the mid-seventeenth century. This is, according to Donati, an artist for whom it is possible to reconstruct a corpus of at least twenty works, which can be placed in a period from 1645 to 1668, but which can be thought to be much broader: the master, Donati writes, was also assisted by an ”inscription attendant,“ a ”skilled lapicida who is distinguished by the rounded regularity of the letters, devoid of the apicatures and graphic devices typical of coeval epigraphic production.“ The Master of 1659, the art historian continues, ”knew how to win the favor of the committency by virtue of expressive formulas from which are banished the graphic flourishes that pleased the heirs of the ’master of the Madonnas on Thrones’; composure of gestures, chastity of drapery, and clarity of composition are the stylistic hallmarks of this master." This sculptor also spread formulas that survived for a long time: indeed, works derived from his language can be traced even at the end of the century.

The first master who can be named is Giovanni di Fabio Carusi da Moneta, an artist previously known to scholars: a native of the village of Moneta, in the hills around the Carrione plain, he was an author with a “marked conservative tendency,” writes Donati, which denoted “a clear preference for expressive sobriety and the adoption of tried-and-true formulas, first and foremost the peculiar tendency to make the figures levitate, as if they were weightless.” Finally, a last “genial anonymous” (so Donati) who can be given prominence is the anonymous 1685 author of a slab in Aulla commissioned by a certain Jacopo di Virgilio Gili, and who stands out for the minuteness with which he sculpts details, in a decidedly animated composition, capable of an image somewhere between sculpture and glyptics, according to Donati. There were also those who attempted to approach the language of Bernini and Algardi: this is the case of the "Master of the Lily Branch," author of a majesty of 1679 in which he attempts to approach the great Roman Baroque sculpture.

It is more difficult to reconstruct the personalities of artists between the 18th and 19th centuries, a period in which the workshops in the area were moving toward a “production that tended to be impersonal, yet worthy of careful investigation in iconography.” On the other hand, the panorama of the 20th century is different, a period in which it is possible to identify a few hands, such as that of the sculptor who between 1923 and 1929 executed seven slabs on the theme of St. Anthony the Abbot. These were the last beats of an art that characterized the Apuan territory for almost five centuries and would come to a halt in the years of World War II.

The work of tracing the majesties of the Apuan Alps, which has been going on for more than three years now, is far from finished, but even if it has not been completed, the amount of material gathered so far has allowed for a study as thorough as the one that led to I maestri delle maestà. Protagonists and Components. A volume of great importance, since Piero Donati’s essay constitutes a first step toward reconstructing the physiognomy of the masters from whose workshops those devotional reliefs that constitute a significant portion of the cultural heritage of the Apuan lands came out. And it is to be expected that further results will emerge in the future.

|

| Who were the sculptors of the majesties, the votive reliefs of the Apuan Alps? |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.