The international art scene is reacquainting itself with the painting of Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida, and Italy, too, has recently rediscovered one of the major protagonists of modern Spanish painting, thanks to the exhibition organized at the Palazzo Reale in Milan in 2022 and the one that ended not long ago at the Spanish Academy in Rome. But numerous other exhibitions around the world have been consummated in the past few years dedicated to the Valencian painter; this lively exhibition activity is thus dispelling the veil of fog that for long decades obscured Sorolla’s name outside Spain, although in his lifetime he had been a celebrated artist sought after by the elite of half of Europe and America.

The valorization of Sorolla, however, is not accidental, and responds to a sensible policy of enhancing his art, promoted by Spanish museums and foundations in view of the centenary of his death, which falls this very year and culminates with a number of important exhibitions alternating throughout 2023 throughout Spain. The project by the name Any Sorolla, through an extensive program aims to bring the figure of the Valencian painter closer to as wide an audience as possible and to provide new content for in-depth study and knowledge of Sorolla’s work. Probably the highlight of these celebrations is the exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Valencia, entitled Masaveu Collection. Sorolla. The exhibition, which opened June 29, aims to pay tribute to the painter through 46 masterpieces from the Maria Crina Masaveu Peterson Foundation, the private entity with the largest number of works by the Valencian painter; it will remain open until Oct. 1, 2023.

The exhibition was curated by María Soto Cano, curator of the Foundation, and is located in the Joanes Room of the Museum of Fine Arts in the artist’s hometown. It is divided into four sections, covering his entire career from 1882 when Sorolla was nineteen years old and in the midst of his training, to 1917, just three years before the painter suffered a stroke that forced him to stop painting. The exhibition then makes use of an evocative layout: in fact, the Spanish painter’s works arranged in a single airy room are arranged in several rows and placed on crystal easels invented by the Italian-Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi and pioneered back in 1968 at the São Paulo Museum of Art in Brazil, making it a museographic case study. The works seem to float on their glass supports, and the easels with their transparent surface do not close off the visitor’s view, but on the contrary allow the entire room to be embraced with a single glance, lightening the space and infusing it with liveliness and vitality. Moreover, although organized in sections, this arrangement allows the audience to build its own path without imposing a predetermined itinerary.

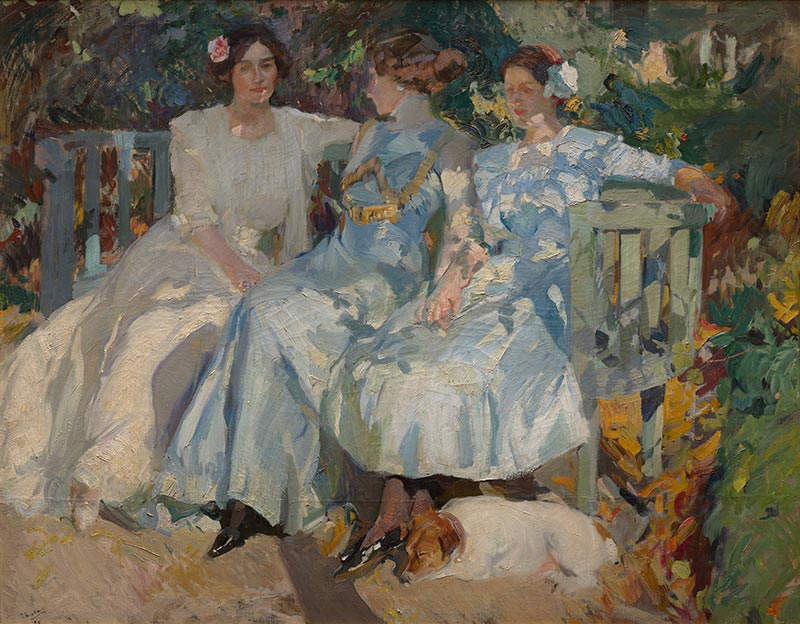

Thanks to this museographic project, still surprising today, great emphasis is given to the back of the works, which is also enhanced by the captions. The latter make it possible to delve into the media used by Sorolla for his paintings, working techniques, signatures, annotations, and other curiosities. Such an expository device finds a perfect match with the artist who made the joie de vivre and poetry of the warm Mediterranean light and coloristic explosions his most typical feature. Thanks to this interplay of transparency, the exhibition hall is flooded with an orgy of lively colors, which invest the visitor from his first steps into the exhibition and accompany him throughout its duration. The quality of the masterpieces in the Masaveu Collection thus enhanced then allows the visitor to get as complete an idea of the Spanish artist as possible.

Born in 1863, just a few meters from one of Valencia’s best-known monuments, the Silk Lonja, the artist’s childhood was certainly not easy; in fact, he was orphaned by both parents at just two years of age and thus grew up with his aunt and uncle, and as soon as he was 13 he began attending an evening drawing school for artisans.

Two years later he enrolled, also in his hometown, at the Academy of Fine Arts in San Carlo. In addition to the first rudiments, his training passed through two canonical stages of the time: copying the old masters, which of course also led him to visit and compare himself with the masterpieces housed in the Prado Museum; and an apprenticeship abroad, which he was able to complete thanks to a scholarship granted by the Provincial Council of Valencia. This enabled him to expand his studies first in Rome between 1885 and 1888 and then to spend six months in Paris, in addition to numerous other visits to Italy.

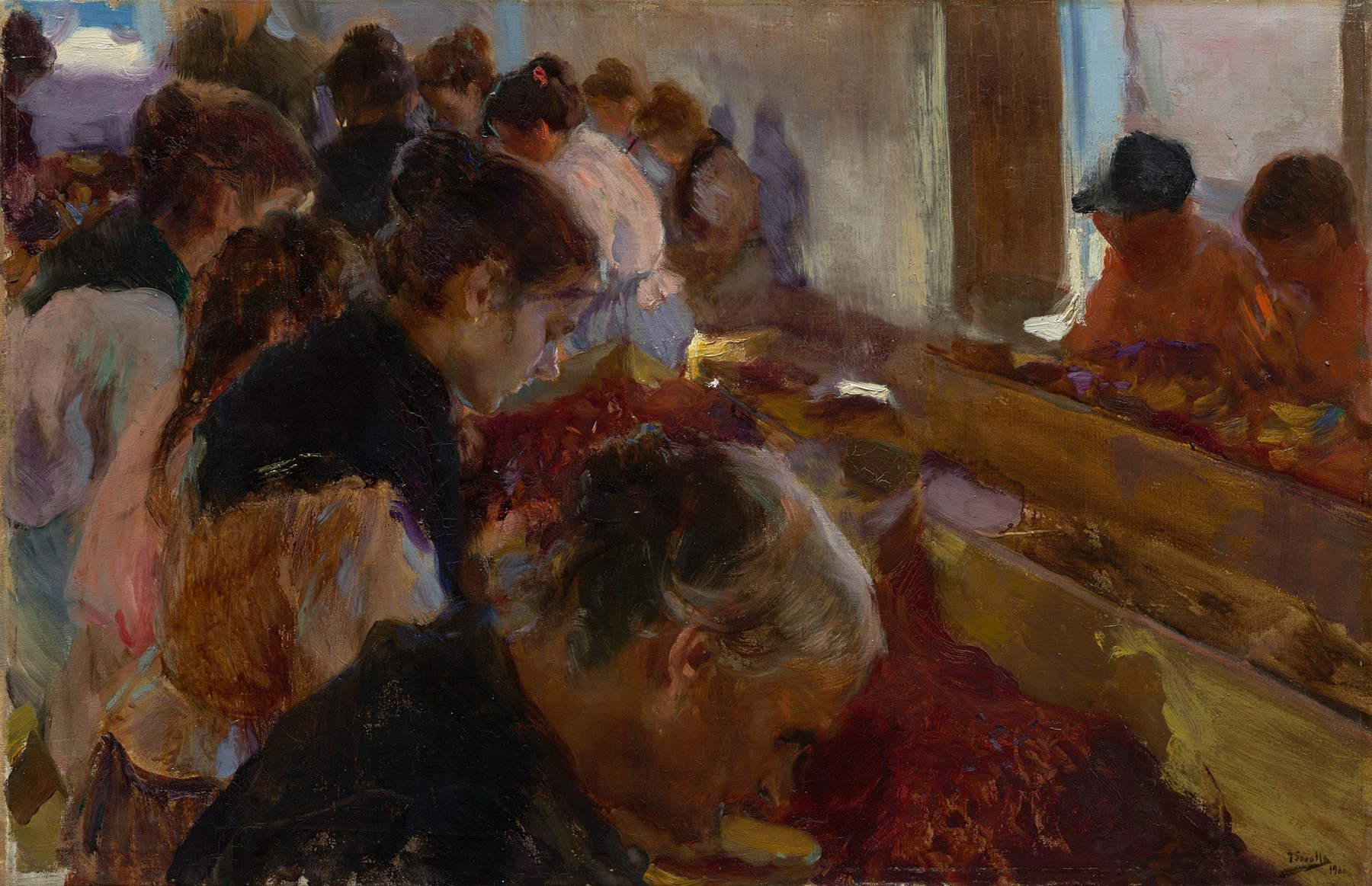

The first section of the exhibition includes five works that reveal how his beginnings are characterized by a frequent use of dark hues, although the Spanish artist went down in history as the painter of light and color. Sorolla’s passion for black in particular, ideal for expressing emotional temperatures but also for giving life to compositions of understated elegance, is inferred from the great masters of the Spanish tradition: Velázquez, El Greco and Goya. On display in the exhibition is precisely a copy by the Valencian of Diego Velázquez’s celebrated masterpiece, the Portrait of Maria Anne of Austria. Several copies are known from the Seville-born painter that Sorolla drew between 1881 and 1884 when he frequented the Prado on a daily basis, but this is the only one that faithfully replicates even its dimensions, instead of merely offering a reduced-format version. Another piece, Últimos sacramentos. Carlos V en Yuste, painted in 1882, is a sketch that refers us to the Valencian’s interest in painting with historical themes, in which the last hours of the Holy Roman Emperor are recounted in a composition with a rather mournful palette, but certainly not without a taste for anecdote. Still strongly marked by Romantic canons is also the work The Kiss of Faust, a commission with a literary theme that he painted during his stay in Assisi.

“Covering such a wide chronological span,” said the curator, “the exhibition allows us to see very well the entire development of Joaquín Sorolla’s painting, the technical, thematic, chromatic and lighting evolution of this painter” . And indeed, the works in the second section, those of the Spanish painter’s early maturity beginning around 1894, are detached from those of his beginnings by a newfound taste for solutions inferred in line with those adopted by naturalism, and by an increasingly radiant chromatic range, thanks in part to the example provided by the Impressionists. At this stage, the artist’s interest is catalyzed by subjects of social and popular themes, as in the splendid painting El Mamón of 1894. The work reflects the influence of Andalusian painter José Jiménez Aranda (1837-1903), an important reference for Sorolla after his move to Madrid.

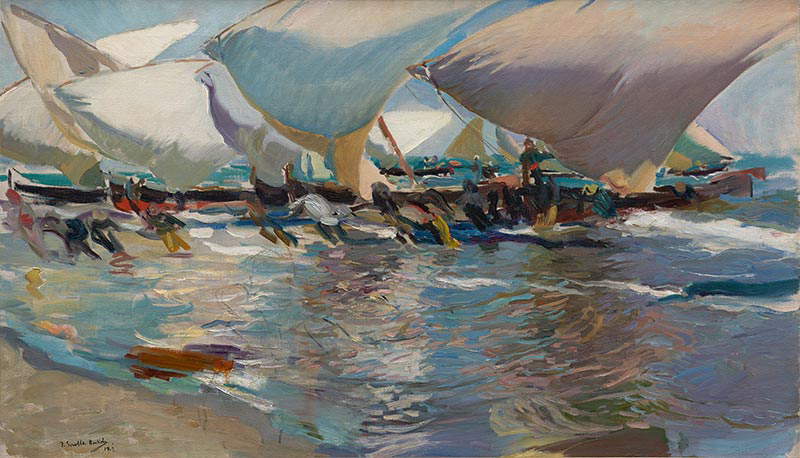

The painting shows the intimacy of a family scene, where the focus is on a new birth, the pivot around which the entire composition develops. The careful descriptive realism is tempered by a virtuoso rendering of light, which penetrating through the windows in the background punctuates the space and shapes the figures, caught in relative obscurity. In works such as La vuelta de la pesca and ¡Triste herencia! the leitmotif of the foaming sea, caught en plein air, which would later make Sorolla’s painting so famous, serves as a backdrop to scenes that are very different from one another. In the first, the interweaving of animal and human strength is rendered with crystalline clarity, while the second canvas shows an investigation carried out on the bodies of polio-affected children, evoked through quick, fluid brushstrokes. The richest and best represented section is that of his maturity, which can be placed between 1900 and 1910, the period that decreed the artist’s success. There are 28 works in this section, and many have as their subject the sea and the golden beaches of Valencia, such as Niños en la playa Estudio para “Verano,” the exhibition’s signature image, 1902’s Playa de València, Niños en la playa and Cosiendo la vela, from 1904. In this period, Sorolla fine-tuned his most typical style, denoted by a quick, full-bodied brushstroke that spreads out in patches of color, while his compositions are built on photographic framing, with a diagonal vision, probing the depths with greater force.

A number of works from recent years testify to the international acclaim that Sorolla’s output achieved: in 1909 the Hispanic Society of New York hosted a grand exhibition of the Valencian painter’s work, an event that drew more than 160,000 visitors in little more than a month. The following year, the same organization asked if the painter would create a cycle representing Spanish and Portuguese history. Of this monumental commission, the exhibition displays some preparatory works, including the canvas painted in 1912 Pescadores de Lequeitio, an allegorical representation of the Basque Country, and Vista de Toledo, instead for Castile.

The Valencian appointment, offered to the public free of charge, stands as one of the most important Spanish exhibition events of 2023, and thanks to the extraordinary quality of the masterpieces represented and the evocative setting, it is configured as an extraordinary experience, in which to immerse oneself in the Mediterranean light, whose intimate secret Sorolla guarded. Moreover, in the same Museum of Fine Arts in Valencia, the not sufficiently satiated visitor can look for a fair number of other exhibited works from the permanent collection. This is therefore a truly unique opportunity to get to know the artist who knew best how to “capture the true essence of Spain, through his works that convey a unique feeling of warmth and vitality.”

The author of this article: Jacopo Suggi

Nato a Livorno nel 1989, dopo gli studi in storia dell'arte prima a Pisa e poi a Bologna ho avuto svariate esperienze in musei e mostre, dall'arte contemporanea alle grandi tele di Fattori, passando per le stampe giapponesi e toccando fossili e minerali, cercando sempre la maniera migliore di comunicare il nostro straordinario patrimonio. Cresciuto giornalisticamente dentro Finestre sull'Arte, nel 2025 ha vinto il Premio Margutta54 come miglior giornalista d'arte under 40 in Italia.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.