One could discuss for hours what Francesco Caglioti writes in the introduction to the catalog of his exhibition Donatello. The Renaissance, when he reiterates that art-historical research tends increasingly to move beyond the approach linked to the vicissitudes of individual masters. The formula of the monographic exhibition on the individual artist is not yet in a slump, but it can be reasonably expected that occasions such as the exhibition that Caglioti has ordered between the rooms of Palazzo Strozzi and the Bargello Museum will be thinning out in the not-too-distant future, for several reasons, even though it may seem paradoxical amid the deluge of exhibitions that hits our country and beyond every year: issues related to the fashions and orientations of studies (for example, times are looming when museums and institutes of culture will focus much of their attention on permanent collections), to sustainability, to the very timing of the so-called culture industry. Here then, with understandable emphasis, the director of Palazzo Strozzi, Arturo Galansino, points out that the exhibition on Donatello is among those that can be considered “unrepeatable.” To listen to the communication machine, in Italy there are dozens of unrepeatable exhibitions every year, but for the exhibition curated by Caglioti the adjective is well spent: those who will have the opportunity to enter first the Palazzo Strozzi and then the Bargello will find themselves before an itinerary that, even if it were to be repeated, will probably be several decades away.

Caglioti’s exhibition managed to gather an impressive number of works, far surpassing the two Donatello centenary exhibitions that were organized between 1985 and 1986: A Homage to Donatello at the Bargello Museum and Donatello and His Own, the latter with two stops, the first at the Forte del Belvedere in Florence and the second at the Detroit Institute of Arts (the Palazzo Strozzi and Bargello exhibition will also go on the road, first to Berlin and then to London, with a visiting itinerary that will be different from the Florentine one, however). To understand the rarity of the exhibition, therefore, a quick comparison with the exhibitions of the 1980s will be appropriate. If theHomage to Donatello, a “conservative” exhibition as Giuliano Briganti called it because it did not move any works, had offered the possibility of a reconnaissance of the Bargello nucleus and was proposed as an event of rather limited dimensions, the Belvedere exhibition was more ambitious, which could not, however, count on loans from the Bargello, and concentrated above all on the young Donatello (this was, moreover, the first exhibition in which the crucifixes of Donatello and Brunelleschi could be seen in comparison). Several of the works now on display at Palazzo Strozzi were on display at the Belvedere: the Bardini Madonna, for example, at the time dubiously assigned to Donatello and now restored to the ranks of the master’s autographs. And then again the bust-reliquary of San Rossore, the St. John the Baptist from Siena Cathedral showing itself, also for the first time, in more favorable conditions of visibility than usual, the Pietrapiana Madonna. The exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi and the Bargello goes further: it is an all-encompassing journey throughout Donatello’s career, from beginning to end, with works that have moved from their location for the first time (this is the case, for example, with the “manualistic” loan of Herod’s Banquet, disassembled for the first time from the baptismal font in Siena Baptistery), with wide-ranging thematic focuses (the section on Donatello of Padua alone could make history in itself), with a quantity of works that is hardly found even in the best-selling monographs.

One could sum it all up in a few words: at Palazzo Strozzi and the Bargello there is almost everything that could be moved. And what little is missing to enrich a complete itinerary on Donatello (the Magdalene from the Museo del Duomo, for example, or the Judith from Palazzo Vecchio) is within reach. The stated aim of the exhibition, is to forcefully bring out Donatello’s personality as an artist of rupture, as an artist so modern that he can be considered a sort of contemporary of Michelangelo despite the fact that the great Buonarroti was born 20 years after the passing of the father of the Renaissance in sculpture, as “the patriarch and symbol of an entire epoch of Western art,” Caglioti writes with transport in the passionate introductory panel that the public finds in the first room of the exhibition. Was it necessary, then, an exhibition, someone might object, to reiterate what is already known? The answer is yes, and the reasons are several. Meanwhile, we might think of Donatello. The Renaissance as an exhibition that lifts the figure of Donatello out of any categorization: he is not just a breakthrough artist, but he is an artist, Caglioti rightly points out, who “introduced into history new ways of thinking about, producing, and experiencing art.” His revolution is not only “technical,” if you will pardon the term: the precise and impeccable comparisons that the exhibition deploys throughout the exhibition show how his merits and his primacies (inventor of the stiacciato, inventor of the Renaissance equestrian monument, inventor of modern statuary) go even beyond those that can be attributed to a Masaccio or a Brunelleschi. And then there is the problem of the “canon” (the term is Caglioti’s) of Donatello’s works, particularly felt between the 1930s and 1950s: although Donatello is such a studied artist that it is difficult to imagine spectacular advances on the investigations concerning him, the Palazzo Strozzi and Bargello exhibition is also an opportunity to re-establish some milestones in the light of the advances of recent years.

The opening of the exhibition is dazzling: Donatello’s beginnings are summed up with the marble David he was commissioned to make in 1408 for one of the buttresses of the apse of the Duomo of Santa Maria del Fiore, moved for the occasion from the Museo Nazionale del Bargello (Donatello’s Hall, as will be seen, has been completely rearranged for the exhibition), which is placed between the two crucifixes, the one by Donatello from about 1408, the famous “Christ peasant” from Santa Croce made famous by Vasari’s memorable anecdote, and the one by Filippo Brunelleschi from Santa Maria Novella (legend has it that Donatello had recognized d’emblée the greater nobility and elegance of the crucifix executed by his friend, concluding that Filippo was allowed to sculpt Christs, and he the peasants). One of the few regrets of the exhibition, in this case also expressed in the catalog by Laura Cavazzini, is that of not having been able to exhibit, in this first room, the Profetino, which is among the works that have not been moved from the Museo del Duomo and which we can consider the artist’s first known work. The focus is therefore on the first masterpieces to overcome this lack, and the profile of the young Donatello is nevertheless fully restored to the public, which is immediately familiarized with an artist who was trained in the Duomo building site, frequented Lorenzo Ghiberti (whose elegances are echoed in the marble David ), befriended Filippo Brunelleschi and engaged with him in this sort of challenge of crucifixes (Donatello’s surprises for its unusual realism but also for its links with tradition: it is perhaps Donatello’s most late-Gothic work), and he established a further equal relationship with Nanni di Banco (Caglioti’s lengthy essay in the catalog, a kind of enhanced biography, makes the terms of Donatello’s bond with Nanni very explicit).

If the first section does not have much to add to the established historiography, the discourse changes in the following room, which is devoted to early productions in terracotta, interesting for many reasons. It is, in the meantime, an opportunity to summarize the most recent acquisitions in perhaps the most difficult field of Donatello studies: it is worth noting that only since the 1970s-1980s, with the research of Luciano Bellosi, has a sort of canon of Donatello’s terracottas begun to emerge. One of the goals of the exhibition is also to help convince of Donatello’s autography those who are still reluctant to recognize as works by the master some terracottas that instead, in the exhibition, are ascribed to him without hesitation. The introduction falls to Jacopo della Quercia’s Madonna and Child made known by Bellosi in 1997 and placed in direct comparison with Donatello’s Madonnas and Child on loan from the Victoria&Albert Museum in London and the Detroit Institute of Arts: the idea is to further demonstrate the goodness of Donatello’s authorship of the London and American terracotta also through direct comparison with Jacopo, since, notes Laura Cavazzini, “the peremptory plasticism” that informs Jacopo’s clay sculpture “is as far removed from the vibrant modeling of Donatello’s inventions.” and likewise “the expertly calibrated volumes in a drastic alternation of solids and voids that, thanks to a daring play of undercuts, generate sharp chiaroscuro contrasts, are antithetical to Donatello’s sensitive pictorialism.” Prominent then is the presence of the Bardini Madonna, one of Donatello’s most astonishing inventions, and whose autography, it may be said, is now given: at Palazzo Strozzi it is nourished by comparison with Nanni di Banco’s Madonna and Child on loan from the Louvre, which, although it manifests a different, more compassed language, is inescapably affected by the innovations introduced by Donatello.

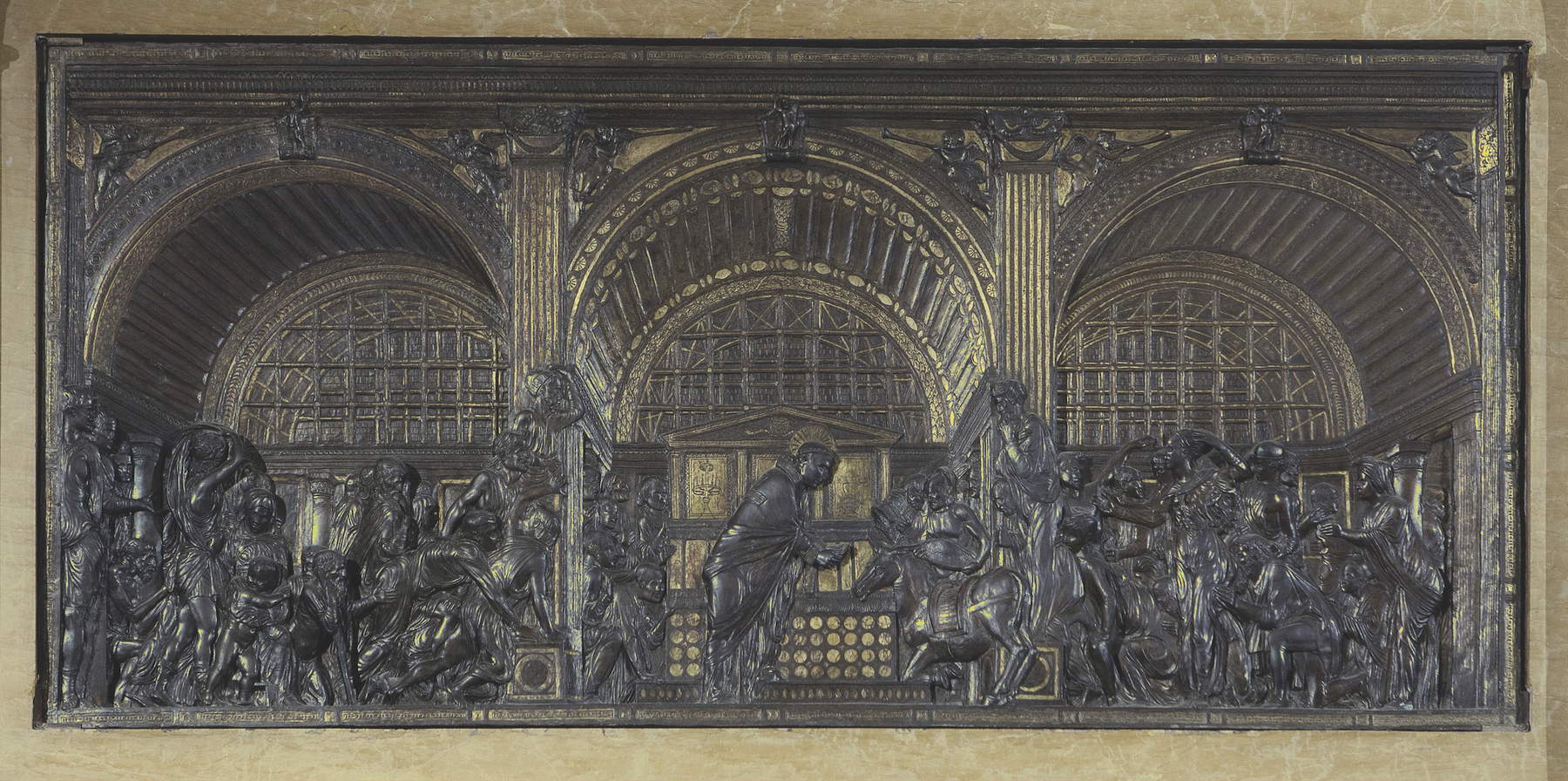

Indeed, it is Donatello, along with Brunelleschi (for whom, however, it is more difficult to reconstruct a reliable and unequivocal corpus of fictile Madonnas), who is credited with reviving the use of terracotta as a means of producing images similar to those on display in the exhibition. Donatello’s tendency to experiment is deepened in the sequence of rooms that open in rapid succession: one gets to know, meanwhile, the metallurgical Donatello (although this was not his main quality) with the St. Ludovico of Santa Croce, with the bust-reliquary of San Rossore, which constitutes one of the pinnacles of Renaissance goldsmithing and which is also to be considered as the first sculptural portrait of the Renaissance (although it is a character that pertains more to legend than to history) and with the two statues of Faith and Hope, the latter of which has just been restored, which leave the Baptistery of Siena for the first time and with which Donatello, writes Gabriele Fattorini, “was able to reveal himself as an unparalleled bronze statuary, aimed at grappling with the goal of sculpting a figure in the round, capable of standing concretely in space like the ancient statues, in the explicit desire to escape the architectural confines of the tabernacle.” Of note, in the third room, is the very high comparison with Masaccio, present with the St. Paul and the two Carmelite saints of the Polittico del Carmine: the great painter was able to take advantage of Donatello’s spatial conception to execute his work. And the revolution that Donatello operated in sculpted space is discussed in the following room, where the aforementioned Banquet of Herod stands out, the centerpiece of the section that gives an account of the achievements that Donatello was able to fine-tune by availing himself of Filippo Brunelleschi’s friendship, translating scientific perspective into sculpture. Entirely new, then, as is well known, is the sense of depth that animates the “stiacciato,” of which the Banchetto offers one of the highest essays: a revolution that not only shakes up Donatello’s sculpture (even the spatial conception that animates that masterpiece of intimism and sweetness that is the Pazzi Madonna responds to these novelties), but which reverberates in contemporary art, as demonstrated by Filippo Lippi’s panel on loan from the Cini Foundation or the more famous Imposizione del nome del Battista by Beato Angelico. The triptych of rooms devoted to Donatello experimenting closes with a section on “spiritelli,” the putti that, though not Donatello’s invention, returned with him to the center of attention, becoming one of the most constant and conspicuous presences in his repertoire. Indeed: for Neville Rowley we owe to Donatello (at the same time as Jacopo della Quercia in the monument to Ilaria del Carretto) the exhumation of this ancient motif. Among the milestones the exhibition aims to establish is the attribution of the two Spiritelli portacero from Luca della Robbia’s chancel for Florence Cathedral: only in the last two decades has light been shed on Donatello’s authorship of the two bronzes, thus resolving a centuries-old problem (the two putti were attributed to Luca della Robbia on the basis of a report circulated by Vasari).

One of the most interesting lunges of the exhibition is devoted to the works Donatello executed in Prato together with his younger colleague Michelozzo, with whom he formed a fruitful partnership whose most famous result is the pulpit in Prato Cathedral, completed in September 1438. The classical language of Donatello and Michelozzo can thus be admired in the gilded bronze capital (some traces remain of the gilding) that came to Florence on loan from the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Prato, and especially in the marble reliefs that adorned the “marvelous pulpit,” as Gabriele D’Annunzio called it: the Dance of the little spirits, writhing frantically to the sound of tambourines with graceful, confident steps, gently swaddled in very light robes, stood as one of the most disruptive novelties of the time. And as evidence of how many suggestions they had stirred, the exhibition displays a drawing from Pisanello’s workshop (but the attribution debate still hangs over the sheet) that rather faithfully copies one of the two Prato reliefs on display at Palazzo Strozzi, as well as the famous reliquary of the Sacred Girdle, a work by Maso di Bartolomeo that echoes Donatello’s festive dance in its decoration. The section on Prato also introduces us to the collective dimension of certain works by Donatello, executed with a wide concurrence of aides and collaborators: an example is the Piot Madonna, characterized by the highly original background composed of alveoli where depictions of amphorae and cherubs executed in white wax find their place. The following small room that houses the two bronze doors of San Lorenzo is further evidence of Donatello’s extraordinary freedom of invention (admire the individual panels), while the section that opens immediately afterwards introduces one of the most interesting themes of the exhibition: Donatello’s stay in Padua.

St. John the Baptist from the Martelli house, the last work Donatello executed in Florence before moving to the Veneto, stands out in the room: the Baptist is depicted as a beardless boy with delicate features, and his destiny would have been to open “a luminous path of imitations,” to use a fine expression by Caglioti. The most tangible demonstration is provided by the San Giovannino by Desiderio da Settignano, the gentlest of Renaissance sculptors, who specialized in marble portraits of children and infants. According to Caglioti, Donatello is said to have brought with him to Padua a model or drawing of the St. John the Baptist, to which he owes a kind of forerunner role toward the bronzes of the altar of the Saint: in any case, even the adolescent Baptist was already sufficient to direct Venetian sculptors and painters, as Schiavone’s St. John the Baptist effectively attests. Further spreading Donatello’s word would have been Andrea Mantegna, among the first to welcome the novelties arriving from Tuscany: the Poldi Pezzoli’s Madonna and Child, one of the exhibition’s top loans, despite being a work from the 1490s, is a painting that still does not abandon the cues Mantegna derived from reading Donatello’s Madonnas. The theory of Northern Italian painters and sculptors inspired by Donatello aligns a number of first-rate names: Marco Zoppo, Giorgio Schiavone (present with the famous Madonna and Child in the Galleria Sabauda in Turin), Bartolomeo Bellano, and Pietro Lombardo. And, speaking of exceptional loans, the next room is perhaps the one that most astounds the audience. It revolves around the Imago Pietatis of the altar of the Saint, one of the most famous Pietà in the history of art: the celebrated, moving bronze relief would become one of Giovanni Bellini’s favorite subjects, present with the Cini Foundation’s Pietà, and would be studied in depth by countless hosts of artists, beginning, again, with Marco Zoppo, who in his Imago Pietatis of the Civic Museums of Pesaro restores a nervous, expressionistic reinterpretation of it. Also arriving from Padua are the bronze Crucifix and another “textbook” work, the Miracle of the Mule, included in one of the exhibition’s most evocative dialogues with the so-called Forzori Altar, a rare terracotta that with the bronze relief of the altar of the Saint shares the spatial conception and that represents, writes Caglioti recalling its entry in the Donatello catalog in 1989, “the only autograph Donatello model for a monumental undertaking that has come down to us, and therefore opens a remarkable glimpse into the master’s mature creativity.” Creativity of the master that is set against the spectacular bronze group by Niccolò Baroncelli and Domenico di Paris for the altar of Ferrara Cathedral, a more immediate reflection of the Saint’s bronzes (the chance to see the two crucifixes in the same room is a more than rare occasion).

The last two rooms in Palazzo Strozzi follow in chronological order the last stages of Donatello’s career. The Chellini Madonna, a splendid bronze from the 1950s that owes its name to its first owner, the physician Giovanni Chellini, who received it as a gift from Donatello himself, is one of the pivots around which the final portion of the exhibition revolves: it is a certain work by Donatello and, recently re-examined, has unblocked the attribution debate on several Madonnas that had remained in doubt. Also from the Victoria&Albert Museum comes the Lamentation over the Dead Christ, which, like another exceptional loan, the St. John the Baptist from Siena Cathedral, gives an account of the extreme Donatello: restless, pathetic, anticlassical. The closure is entrusted to the great bronzes of old age (the Protome di cavallo also known as Testa Carafa, a fragment of the unfinished equestrian monument to Alfonso the Magnanimous in Naples, stands out), while the comparison between Donatello’s Crucifixion from the Bargello and the counterpart relief by Bertoldo di Giovanni, one of Donatello’s greatest and most skillful “creations” (and who of Donatello’s relief offers a more sober and less eventful interpretation) refers the public to the three sections set up at the Bargello Museum.

For the occasion, as anticipated, Donatello’s Salone was rearranged around three major masterpieces, the bronze St. George, Marzocco, and David. The aim, both in the Salone di Donatello and in the two small rooms on the first floor reserved for temporary exhibitions, was to compose a Donatello anthology to document the fortunes of the master’s inventions. Of great effect is the arrangement of the back wall of the Salon: the St. George stands in dialogue with two paintings from Andrea del Castagno’s cycle of illustrious men, the Farinata degli Uberti and Pippo Spano, which “participate in the exhibition,” writes Francesco Caglioti, “both as striking reflections of those two sculptures” (i.e., the St. George and the David), "and also to allude to the first presentation that the David could have in a room of the Medici’s ’Old House,’ in the midst of a lost cycle of Famous Men similar to the one at Villa Carducci in Legnaia, but frescoed by Bicci di Lorenzo." Testifying to the David ’s further fortune parade Desiderio da Settignano’s Victorious David, on loan from the National Gallery in Washington, the bronze counterpart by Bartolomeo Bellano arriving instead from the Metropolitan in New York, Antonio del Pollaiolo’sHercules at Rest, and of course one of the hosts, Verrocchio’s David. It moves to further amazement the presence of a sheet by Raphael: his Four Soldiers from the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford is meant to make clear the fascination Donatello exerted on Urbino (the central figure of the sheet is a copy of St. George).

The exhibition’s finale devoted to the fortunes of Donatello’s Madonnas, with two rooms revolving around, respectively, the Madonna of the Clouds and the Madonna of Pietrapiana, and the Dudley Madonna. An early work, a mature work, and a late work, then: three masterpieces that rank among the most lyrical works in Donatello’s entire output. The reliefs, compared with a selection that spans two full centuries and even goes slightly beyond, are intended to give an account of how Donatello helped build the so-called “modern manner”: the comparison between the Pietrapiana Madonna and Giovanfrancesco Rustici’s very faithful Madonna of Fontainebleau shows how almost a century later Donatello still exerted a very strong ascendancy. And the same can be said of Francesco da Sangallo’s St. John the Baptist, which dialogues at a distance with Donatello’s in Casa Martelli. Even more conspicuous are the comparisons that make up the last room, centered around the Dudley Madonna, identified by Caglioti as Donatello’s single most widely followed work, and for that reason deserving of an exhibition in its own right. Evident are the debts manifested by Michelangelo’s Madonna della Scala, faithful copies are Baccio Bandinelli’s drawings and Bronzino’s Madonna and Child from a private collection, while the comparison with the Madonna and Child in the Pitti Palace attributed to Artemisia Gentileschi seems decidedly more forced: and although Caglioti himself, from the pages of the catalog, asks for an effort of imagination from the visitor since the Gentileschian image “does not at first glance reveal stringent borrowings from Donatello,” the link cannot but seem a little far-fetched, not to mention the fact that we are talking about a work whose very autography is more than doubtful. It is the work that bids the visitor farewell: but even without its presence, the idea of a Donatello who is alive even at a great distance in time still comes direct and ringing.

What image, then, do we get of Donatello from the Palazzo Strozzi and Bargello exhibition? Who is the Donatello who emerges at the end of the exhibition itinerary? It has been said that perhaps the main aspiration of the exhibition is to present him as an artist capable of rising even above a Masaccio or a Brunelleschi, who brought the Renaissance to painting and architecture, because Donatello, Caglioti insists, was responsible for the “cultural leap toward praxis - even before the concept - of the author’s extreme individual originality, in tireless and pervasive search for anything that could subvert the institutional customs of art.” Here, then, is the Donatello who stands out from the exhibition: an artist with a modern and independent mentality, a continuous experimenter, an artist who was also contradictory if you will, so much so that scholars have long struggled (and still struggle) to find him a satisfactory pegging, assuming that Donatello can avoid evading classifications. What is surprising about Donatello, and which appears from the exhibition in all its manifest and concrete evidence, lies in the fact that his revolution lasted, first and foremost, the entire time of his existence. There was no moment in his career when this great sculptor posed, paused to pause, experienced involutions or backward steps, stopped on his admittedly great achievements. And then, it is surprising how strongly his lessons resonate even over the long haul.

But there is a fact that is perhaps even more surprising, and which was well emphasized by Giorgio Bonsanti in his 2000 essay on the marbles of the Prato pulpit: Donatello, wrote the scholar, is an artist outside of time, capable of absolute originality, able to assert forcefully his own extraordinary individuality by purifying it “of every external cultural reference.” His art, we might say, is imbued with a humanity that belongs to every era. In five very effective words, according to Bonsanti: Donatello is an artist who is “contemporary always and to anyone.” An artist who is modern even today. This is Donatello’s stature: the exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi and the Bargello Museum, which belongs to that singular genius of exhibitions that know how to be founded on more than solid scientific projects and at the same time know how to draw large crowds, brings it out in all its grandeur.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.