The exhibition Rubens Van Dyck Ribera. The Collection of a Prince, hosted on the second floor of Palazzo Zevallos di Stigliano, home of the Naples “branch” of the Gallerie d’Italia, opened to the public on December 6, 2018. The exhibition aims to collect, in the rooms of the same palace that had housed them since the last third of the 17th century, the paintings formerly belonging to the Flemish merchants Gaspare Roomer (Antwerp, 1595 - Naples, 1674), Jan (c. 1590 - 1671) and Ferdinand Vandeneynden (1626 - 1674), later passed, through inheritance, to the Colonna and Carafa families and now scattered among public museums and private collections in Europe and the United States. For “insiders,” particularly Neapolitans, the names of the collectors are not new, but they certainly are for the general public, to whom, for the first time, is presented the richness of a “princely” collection, created, however, by a large family of merchants and financiers, at the head of a commercial empire with trade and interests extending from Egypt to Scandinavia.

The exhibition itinerary winds through seven rooms on the palace’s main floor and approaches works by individual artists, belonging to the same “current” or from the same provenance, format and genre. The curators, Antonio Ernesto Denunzio, together with Giuseppe Porzio and Renato Ruotolo, give an account, through the extensive bibliography in the catalog, of the long gestation that led to the birth of this exhibition, through studies that go back more than thirty-five years (this is the case of Ruotolo, who in 1982 published the inventory of 1688 that will be discussed later).

Among modern scholars, it was first Francis Haskell (London, 1928 - Oxford, 2000), in his dense 1963 Patrons and Painters(translated into Italian three years later under the title of Patrons and Painters), who observed the incredible case of the Roomer collection. The English scholar acknowledged the magnate’s boundless fortune, amounting to some five million ducats, and identified, in a collection of more than fifteen hundred paintings, a particular predilection for “the grotesque, the horrid, the cruel, which the painters of Naples were most adept at satisfying.” Hailing from his collection were the intoxicated Silenus and a Flaying of Marsyas, both by Jusepe de Ribera (Xàtiva, 1591-Naples, 1652) although only the former is on display, as well as are paintings by Battistello Caracciolo (Naples, 1578 - 1635), the young Massimo Stanzione (Naples, 1585 - 1656) and the French Valentin de Boulogne (Coulommiers, 1591 - Rome, 1632) and Simon Vouet (Paris, 1590 - 1649). A very large part of his collection was then occupied by paintings with “Nordic” subjects, such as still lifes with game and highly polished silverware, small landscapes and sea storms; completely absent from it, according to the Haskellian reconstruction, were, on the other hand, the clarity and serenity of Roman classicism and Venetian color. In any case, the centerpiece of the Roomer collection, entered there around 1640, and the glittering masterpiece on display is, without a doubt, Pieter Paul Rubens ’ Banquet of Herod (Siegen, 1577 - Antwerp, 1640), now in the Scottish National Gallery in Edinburgh, to whose description by Haskell very little can be added: “The feast takes place in a crowded hall suffused with luxury and extravagance, while richly dressed guests, a boy with a monkey, and black servants stand watching. In the foreground a young woman, tall and with a flushed face, holds on a silver platter the severed head of John the Baptist, and Herodias’ daughter, with a strange and ambiguous expression on her face, is about to pierce the insulting tongue with her fork, a touch of cruelty that must have particularly fascinated Roomer. Only Herod, sitting at the head of the table, holding up his chin with his hand, seems to realize tormentingly that a terrible injustice has been committed.”

|

| Jusepe de Ribera, Drunken Silenus (1626; oil on canvas, 185 x 229 cm; Naples, Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte) |

|

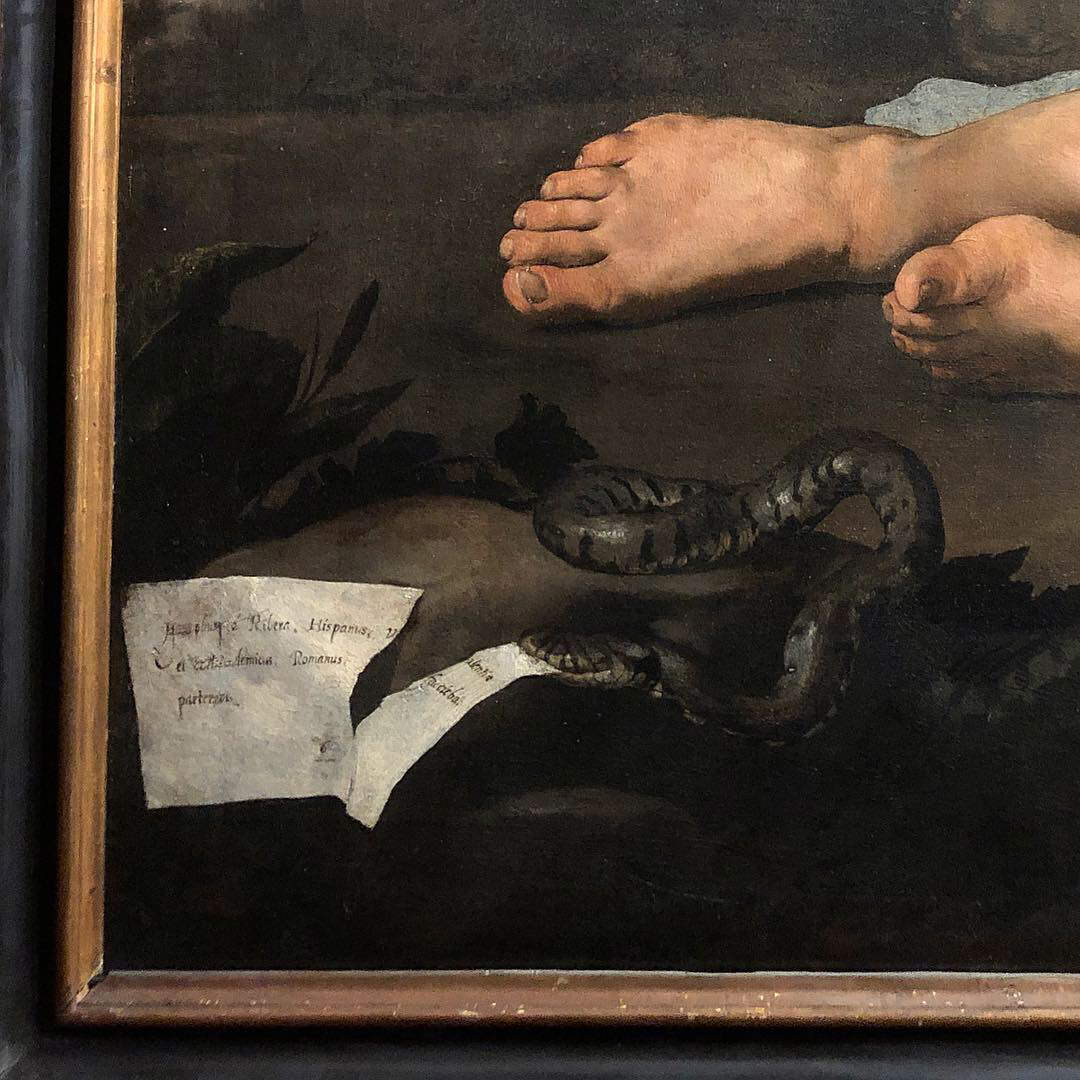

| Jusepe de Ribera, Sileno ebbro, detail of the artist’s signature |

|

| Pieter Paul Rubens, Herod’s Banquet (c. 1635-38; oil on canvas, 208 x 272 cm; Edinburgh, National Galleries of Scotland) |

The eccentric presence of an Antwerp painter in the dealer’s collection could be explained not only by their common Flemish provenance, but also through a network of contacts and acquaintances that kept Roomer constantly updated on what was happening in Europe’s major commercial centers. Moreover, Roomer himself sent paintings by Neapolitan artists to Flanders, and it was, perhaps, thanks to his mediation that the Maestra di scuola by Aniello Falcone (Naples, 1600/07 - 1665), now in Capodimonte, and a painting by Ribera were in Antwerp in 1673 in the collection of the merchant Peter Wouters. When Roomer died in 1674, at least fifty of his paintings passed to Ferdinand Vandeneynden, son of his former business partner, Jan.

The Vandeneyndens already possessed a collection of paintings that had certainly been much affected during its formation by the taste of Roomer’s, the most important in the city and the only one not to return to Spain with the succession of viceroys. In the Vandeneynden collection landed, then, Rubens’s painting, the intoxicated Silenus of Capodimonte and, perhaps, some works by Mattia Preti (Taverna, 1613 - Valletta, 1699), much appreciated, later, by Ferdinand and whose Banquet of Herod, a Beheading of St. Paul (formerly Roomer) and a St. John the Baptist admonishes Herod are on display in the same room. Vandeneynden died a few months after Roomer, but his collection did not move from the palace on Via Toledo, purchased by the Zevallos and enlarged from 1663 by him and his father Jan. In 1688, an outstanding personage such as Luca Giordano (Naples, 1634 - 1705) drew up a detailed inventory of it in order to divide it among the merchant’s three daughters and heirs: Catherine, Giovanna and Elisabeth. Giovanna and Elisabetta married, that same year, Giuliano Colonna di Stigliano and Carlo Carafa di Belvedere, respectively, and from this time two groups of paintings followed two distinct lines of inheritance.

What characterized the Vandeneynden collection (Ferdinand’s work, rather than Jan’s) was a preferential relationship with Mattia Preti and Luca Giordano, made evident, as we have seen, also by the fact that it was the latter who drew up the inventory of paintings, recognizing among them several of his works “in the manner of.” In addition to the Birth of Venus, from the Musée Vivant Denon in Chalon-sur-Saôn, the exhibition includes a very interesting painting by Giordano in which the artist, imitating the style of Albrecht Dürer (Nuremberg, 1471 - 1528), went so far to counterfeit his monogram in order to demonstrate his mimetic skill and, according to the amused De Dominici, swindle the prior of the Carthusian monastery of San Martino, who bought it as an original for six hundred scudi. Compared to Roomer’s taste, a series of paintings by “Roman” classicist painters, particularly belonging to the “neo-Venetian” current, such as Nicolas Poussin (Les Andelys, 1594 - Rome, 1665) and Giovan Battista Castiglione known as Il Grechetto (Genoa, 1609 - Mantua, 1664), were making their way into the Vandeneynden collection. Also unusual for a Neapolitan collection was the appreciation for the Bolognese classicists, represented by a comic scene by Annibale Carracci (Bologna, 1560 - Rome, 1609), identified in awork now in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, and by an altarpiece, recognized by Porzio as the work of Francesco Albani (Bologna, 1578 - 1660) and now in the basilica of the Incoronata Madre del Buonconsiglio in Capodimonte.

An “annotated list of paintings” precedes the catalog of works in the exhibition, and in it Giuseppe Porzio and Gert van der Sman propose new and unpublished identifications; while, at the end of the volume, Luigi Abetti reports theentire inventory of the Vandeneynden estate, returning the gigantic inheritance divided among the three heirs, which also included tapestries, sculptures, carriages, silver, linens, furnishings, credits, annuities, real estate, lands and noble titles and amounted to more than one million one hundred thousand ducats. It is probably precisely the presence of an exceptional connoisseur like Giordano that allows an operation, perhaps risky, but, nevertheless, necessary, such as the attempt to identify in the corpora of the mentioned painters the works attributed to them in the ancient inventory. Thus, with due caution, it was possible to detect some interesting presences in the Vandeneynden collection. These include, perhaps, three copies from paintings by Caravaggio (Milan, 1571 - Porto Ercole, 1610), namely, a Crowning with Thorns, a Kiss of Judas and a Flagellation; three paintings by Guercino (Cento, 1591 - Bologna, 1666), of which a Samaritan Woman at the Well is present in the exhibition; the three mentioned masterpieces by Mattia Preti, almost a “painter of the house”; several works by Ribera, Giordano and Poussin (a copy of the Holy Family with St. John is in the exhibition , the original being an immovable work from the Metropolitan Museum in New York). Then there were several paintings by Aniello Falcone and about twenty by Andrea Vaccaro (Naples, 1604 - 1670), local exponents of Roman classicism; as well as landscapes, “bambocciate,” still lifes and land and naval battles by Nordic authors: a strong and characterizing component of the collection, but one with which Giordano, as Porzio keenly notes, was less familiar.

|

| Mattia Preti, Banquet of Herod (ca. 1655; oil on canvas, 177.8 x 252 cm; Toledo, Ohio, The Toledo Museum of Art) |

|

| Annibale Carracci, Comic Scene with Masked Child (c. 1582-85; oil on canvas, 90.2 x 69.8 cm; Francesca and Massimo Valsecchi Collection, on loan to Cambridge, The Fitzwilliam Museum) |

|

| Luca Giordano, Probatic Pool (1653; oil on panel, 96 x 87 cm; Athens, National Gallery Museum Alexandros Soutzos) |

|

| Giovanni Francesco Barbieri known as Guercino, Christ and the Samaritan Woman at the Well (1640-41; oil on canvas, 116 x 156 cm; Madrid, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza) |

Several Neapolitan guidebooks, in addition to Dominici’s Lives , counted paintings from the Vandeneynden collection, and even Tommaso Puccini, the future first director of the Uffizi, is said to have visited the Colonna di Stigliano collection during his Neapolitan trip, into which, as mentioned above, some paintings formerly belonging to Vandeneynden had meanwhile entered.

The operation set up by Palazzo Zevallos di Stigliano is commendable, since it finally gives an account of the richness of a collection that was born, transformed and dismembered over nearly four centuries, and it does so in a “container” that could not be more philologically suitable. The exhibition is within the framework of other high-profile exhibitions that have already involved Antonio Ernesto Denunzio and Giuseppe Porzio, such as the exhibitions on Louis Finson (Bruges, 1580 - Amsterdam, 1617) in 2013 and on Tanzio da Varallo (Alagna Valsesia, c. 1582 - Varallo, 1633) in 2014, and which are the result and only possible outcome of long research, documentary and otherwise. Within numerous private initiatives (which, at times, dangerously claim the absence of planning and adequate preliminary research), Palazzo Zevallos di Stigliano stands as a most virtuous example of public-private cooperation, of good curatorial practices, of an administration that leaves it to the specialists, of cooperation among international scholars, young and not so young, always able to say well and, once it seemed superfluous to have to specify, to say something. The only flaw, perhaps, for a catalog that is rightly proposed as a useful tool for future research on the Vandeneynden collection and other Neapolitan collections, is the absence of an index of names that is not limited to those in the 1688 inventory, but includes those in the entire catalog. The year has just begun, but the premises are excellent. Rating: 9+.

The author of this article: Vincenzo Sorrentino

Nato a Napoli nel 1990, si è laureato a Pisa in Storia dell’arte nel 2014 e si è addottorato a Firenze nel 2018, all’interno del programma “Pegaso” in cui sono consorziate le Università toscane. Ha svolto un internship di sei mesi nel dipartimento di scultura della National Gallery of Art di Washington D.C. e da gennaio 2019 è iscritto alla Scuola di Specializzazione in beni storico artistici dell’Università di Firenze.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.