by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 29/11/2017

Categories:

Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Treasures from the wreck of the Unbelievable' in Venice, Palazzo Grassi and Punta della Dogana, April 9 to December 3, 2017.

The history of fake archaeological finds is at least as old as the interest in archaeology. Already Ascanio Condivi, Michelangelo’s first biographer, recounted that the genius of Caprese “set himself to make of marble a God of love,” so similar to ancient statues that Lorenzo the Magnificent told him that “if you would arrange it so that it would seem to have been under the ground, I would send it to Rome, et it would pass for ancient, et much better you would sell it.” The Cupid (now lost) was thus passed off as an ancient work, and as such sold, for the exceptional sum of two hundred ducats, to the powerful Cardinal Raffaele Riario, to whom word of the deception later reached him: but the great talent of that young sculptor, so adept at counterfeiting a work, aroused not furious ire but unanimous appreciation, and the artifice served to open to him the doors of the high spheres of the Papal State.

In short: the story that Damien Hirst concocted for his fanfic exhibition in Venice, in the two venues of Punta della Dogana and Palazzo Grassi, already starts from assumptions that are anything but new. But that is not the point. The point is that the British artist has been able to orchestrate a prank, as mammoth as it is subtle, to the detriment of all visitors to his big show: and for that alone, the now-incorporated bad boy from Bristol deserves open applause. The storytelling devised for the massive show, titled Treasures from the wreck of the Unbelievable (“Treasures from the wreck of the Unbelievable”), tells us of a freedman from Antioch, Cif Amotan II (obvious anagram of “I am a fiction”), who reached a level of affluence that enabled him to amass an impressive collection of artworks, objects, jewelry from all over the ancient world, then loaded all together on a ship, the “Incredible,” which unfortunately sank off the east coast of Africa. A salvage campaign, begun in 2008 and financed by Hirst himself, would allow the works to be pulled from the depths of the ocean and displayed in Venice in a major exhibition, accompanied by contemporary copies of the supposedly resurfaced antiquities. Accompanying the exhibition are photographs of divers intent on the work of retrieving the works from the waters.

|

| A room of Damien Hirst’s exhibition at Punta della Dogana. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| A room of Damien Hirst’s exhibition at Punta della Dogana. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Damien Hirst, The diver. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Damien Hirst, Hydra and Kali. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

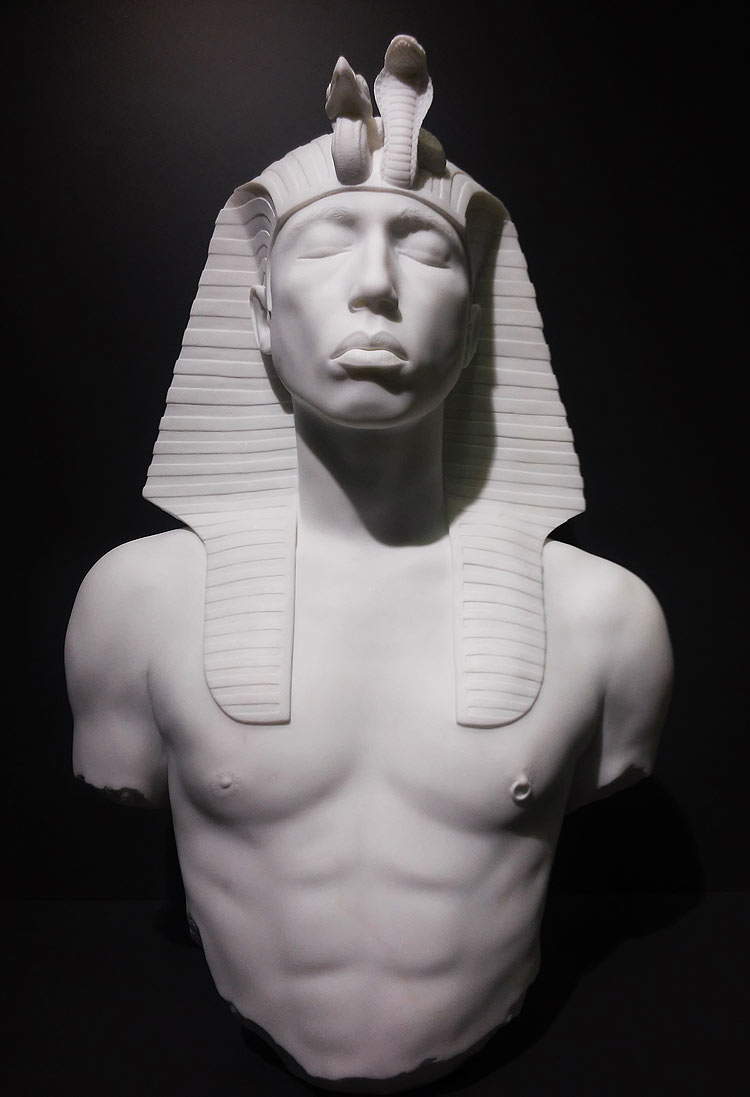

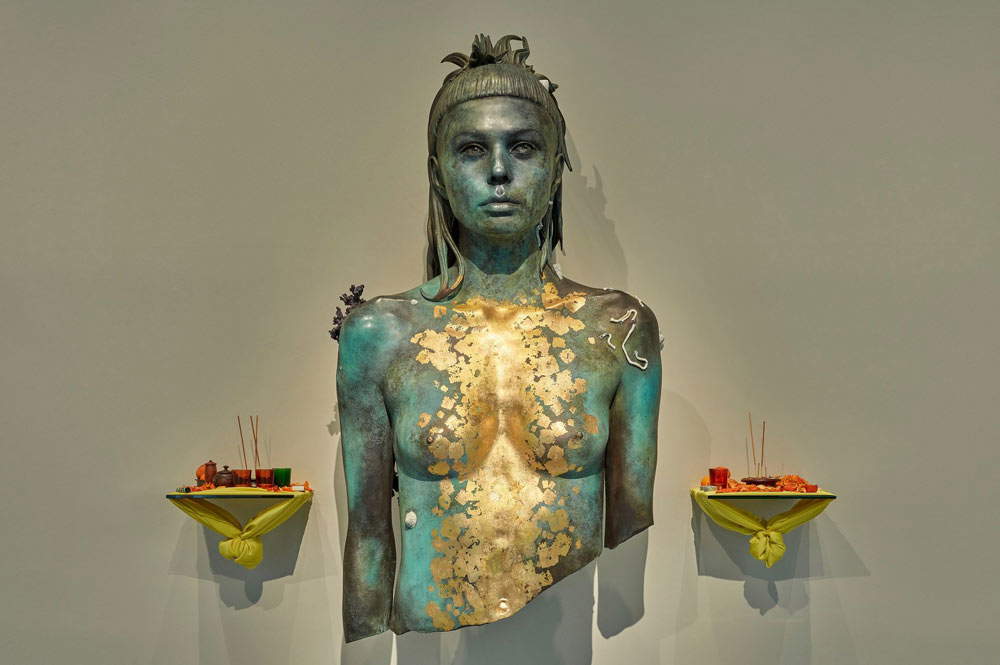

This is the narrative of the exhibition, as it is also poured out by the guides, evidently instructed to pass off as true the story of the freedman, the collection and the find, and to reveal the fiction to the public as the exhibition progresses (or at least in such terms the guided tour followed by yours truly took place). In Hirst’s intentions, the story should initially be believable, and as the rooms progress, certain elements (a sort of golden transformer, an Egyptian pharaoh with the connotations of Pharrell Williams, the goddess Ishtar in the guise of Yolandi Visser of the Antwoord) should instill some doubts in the visitor: toward the end (if one wants to start at Punta della Dogana), a group composed of two characters, namely Damien Hirst and Mickey Mouse, makes obvious to everyone (even those who, a few days before the closing, had been totally unaware of Hirst’s machinations) the hoax to which the artist wanted to subject the public. Of course, then the “rediscovered” works appear from the outset to be so lacking in credibility (unless one has never set foot in an archaeological museum, or ever leafed through an art history book) that any intent to develop a serious reflection falls inexorably into the void. What unravels before the gaze of the visitor to Palazzo Grassi and Punta della Dogana is a mega-accomplishment, the cost of which is as unbelievable as the name of the fake sunken ship, and which is made up of continuous quotations that often result in copying: there’s the slave whose pose recalls that of Michelangelo’s Rebel Prisoner in the Louvre, there’s the Minotaur that hints at Picasso, there’s the gilding and kitsch of Jeff Koons, there’s the grimaces that tear at faces and seem to come from Messerschmidt’s sculptures, there is the gigantic monster of Palazzo Grassi that is none other than William Blake’s “ghost of a flea,” there is even the fishing with both hands from Daniel Spoerri’s repertoire, with works such as The sadness and the unicorn skulls put in circles taken by weight from earlier works by the Swiss-Rumanian artist. So much so that there are even those who have spoken of plagiarism(more than obvious similarities with Jason deCaires Taylor’s “underwater sculptures,” moreover presented at this year’s Biennale, at the Grenada Pavilion, but this is not the only case).

As many have observed, in the midst of the post-truth era, Damien Hirst’s exhibition represents the (consumer) art product best suited to our times: a kind of fake news for fashionable exhibition goers, a verisimilitude story where everything can be true, but can at the same time be false, as denounced by the large inscription that greets the visitor at the entrance to Punta della Dogana and reads “Somewhere between lies and truth lies” (a pun in English, untranslatable into Italian, which sounds “The truth lies somewhere between lies and truth,” where the verb “lies” can mean “lies,” but also “lies”): a kind of pop reworking of the Picassian assumption “art is a lie that allows us to realize the truth, or at least the truth that we can understand.” Therefore, if you believe it, that is perfectly fine. If you don’t believe it, you will have spent an hour wandering through the tedious expanse of kitschy works that, amidst the petty mythology from an episode of Voyager, cheesy technical achievements (probably in a deliberate way to make the joke even more sadistic) and bilious displays of assorted golds and precious materials, have no other purpose than to glorify the titanic ego of their creator (and to procure him new buyers). And if for Picasso the lie of art is the way to know the truth, for Hirst, interested less than nothing in what we all have to say about him, it is simply the way to revive himself in a time of distress, all with the support of his friend François Pinault, who graciously provided resources and offered hospitality to the sumptuous end-all-be-all joke that mocks everyone, starting with all those gullible people who went and continue to go to see the exhibition just because someone presented it as a “must-see event.”

|

| One of the many photos of the fake finds |

|

| Damien Hirst, Cat. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The slave inspired by Michelangelo’s Rebel Prison. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The unicorn skull taken from Spoerri. Ph. Credit Prudence Cuming Associates © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS/SIAE 2017 |

|

| The Transformer. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

In short: in all cases, Hirst made fun of you. All the more so if you came out of the exhibition enthusiastic and willing to glean profound reflections from a Mickey Mouse covered in fake encrustations or if, conversely, you pour all your bile on the British artist for being made a fool of by the hypertrophic Venetian sham. And in the meantime, Damien Hirst, rubbing his hands together in imagining the throngs of moneyed yokels who harbor sights toward the exhibits (clearly, as of next week, the works will end up in collections scattered halfway around the world: as Scott Reyburn aptly wrote in the New York Times, this is an exhibition tailored to “the trophy-hunting mentality of wealthy collectors”), he must surely be laughing at me writing about him, at my colleagues who have flocked to Venice to do the same, of those who talked about the exhibition even though they had not even set foot in it, of the ignorant hipsters on the prowl for harassing selfies who for the entire duration of the exhibition harassed us with their annoying presence and with whom we had to do battle in every single room, of the idiot tourists who, with three days in their entire lives to see Venice, wasted half of them for Treasures from the wreck of the Unbelievable, and of course also of you, who willingly participated in this circus, a kind of Hollywood kolossal rich in special effects but extremely poor in substance (and which, however, at least, gave work to dozens of sculptors who worked for years with the purpose of giving substance to Hirst’s mocking megalomania). As an artistic endeavor, it will leave no mark, and rightly so, since surely even Hirst did not set out to leave an indelible mark on art history. The only echo that will probably resonate after this exhibition will be that of the “wows” of amazement from those who went to Punta della Dogana but never set foot in San Giovanni Crisostomo to see the works of Giovanni Bellini and Sebastiano del Piombo. And perhaps also that of dutiful congratulations to a great Damien Hirst, for being able to organize such a fine prank.

|

| Pharaoh in the guise of Pharrell Williams. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The goddess Ishtar with the likeness of Yolandi Visser. Ph. Credit Prudence Cuming Associates © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS/SIAE 2017 |

|

| Damien Hirst, Collector and friend. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The Mickey Mouse...found in the depths. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.