Luca Pignatelli (Milan, 1962) is an artist rather reluctant to discuss with critics the meaning his works imply and conceal. He recalled this himself at the presentation of his solo exhibition in Carrara, at Palazzo Cucchiari, and the former director of the Uffizi, Antonio Natali, who together with Massimo Bertozzi serves as curator of the Apuan exhibition, also reiterates it in his catalog essay. He does not like to talk much about his works because he prefers the viewer to get an idea of what is in front of him. But that he is an educated and passionate artist can be understood as much from his cultural references, which range from Wölfflin to Leonardo da Vinci, passing, of course, through ancient statuary, as from the stories about the genesis of certain of his works, which often spring from fortuitous encounters with materials found quite incidentally. One glimpses, in the way of working of this refined artist who models, shapes, reverses and rereads, a symbolic reference to that memory that is the central motif of his careful and original reflection.

|

| Luca Pignatelli in front of one of his works |

Nannucci, with his neon signs, said that all art was contemporary. The evidence can lead us to say that, for Pignatelli, all art is contemporary. The past in Pignatelli returns as a faded shadow corroded by time, but no less evocative and powerful, on the contrary: the burden of centuries perhaps makes the images even stronger and more communicative. Needless to try to contextualize: manualistic reminiscences lead us to recognize, in the busts of the Roman emperors emerging from open black gashes on oxidized backgrounds, a Caligula, a Septimius Severus, a Pertinace, but the absence of apparatuses that help with certainty to identify names, periods, historical moments, is a precise choice of the artist (we even arrive with extreme but thoughtful simplification, to title almost all the works in the cycle Emperor ), who wants to avoid conditioning the viewer, to make his vision tied to prior acquisitions, that his attention dwell on the signifier rather than the meaning. History, in other words, does not consist of events that follow one another in a straight line: it is an infinitely flowing circle, as many of the ancient thinkers (Herodotus and Polybius come to mind) tried to demonstrate.

The effigies of the emperors appear to us motionless, fixed in their austere solemnity, but they have traversed centuries of history to reach us: their rediscovery by Renaissance artists (and Natali advances a comparison with Donatello and Brunelleschi, who in the early fifteenth century traversed the ruins of ancient Rome in search of real treasures on which they would base their poetics), their assumption as an unattainable model of supreme beauty for the neoclassicists (a sublimation, this one, recalled in Pignatelli’s busts by the vines inserted on the zinc the small heads evoke the holes left by the repere with which Canova and colleagues kept track of the proportions of their sculptures) and the momentary arrival at industrial society, with its abrasions, plates and sheets, and galvanized iron. It happens, therefore, that the ancient image slips unscathed (or almost unscathed) along the course of events and, through the necessary stratification it undergoes, becomes charged with new meanings: what occurred in the past remains as a memory no longer linked to a precise event, but which resurfaces each time with new connotations to tell us a story, reinforce a conviction or, vice versa, question it, try to arouse different sensations each time. Sensations that, moreover, when observing Luca Pignatelli’s works often turn into vivid emotions, as when one admires a female portrait whose classic beauty is partly obscured by the leaden accumulations that dirty the image, and partly affected by the inserts that, as if they wanted to begin a destructive action, communicate a sense of pain, melancholy, loss. The image remains the same, but seems burdened, seems to want to communicate something new, a recent feeling, experienced throughout history. After all, the past is, in Pignatelli’s own words, a quotation that becomes “exact repetition,” but “in a different context.” Similar approach to that of Adolf Loos, according to whom “the present is built on the past just as the past was built on the times that preceded it,” and who in Vienna quoted the portico of St. Michael’s Church in the Looshaus or directly inserted reproductions of the Parthenon frieze in the Haus Rufer.

|

| The room with the emperors |

|

| Luca Pignatelli, Emperor (2016; mixed media on galvanized iron, 100 x 100 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| Luca Pignatelli, Emperor (2016; mixed media on galvanized iron, 99 x 100 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| Luca Pignatelli, Emperor, detail |

|

| Luca Pignatelli, Female Head (2016; mixed media on galvanized iron, 285 x 191 cm; Private Collection) |

There is no shortage, then, of probabilistic openings: chance, Pignatelli often has occasion to reiterate, plays a fundamental role in his research. Natali calls into question, in an effective comparison, Leonardo da Vinci, who “advised artists to observe the clouds in the sky to derive compositional inventions from them. And he suggested, again, to soak a rag in colors and then to throw it wet on a wall: the imprint that would come out of it, obviously random, would suggest scenes of battles or visions of countries or anything that the inspiration granted to the heart.” It seems that in Pignatelli the memory of the suggestions of Vinci’s genius is evident. Point of departure is always an image captured from a precise point of view: this is what Heinrich Wölfflin taught in his Wie man Skulpturen aufnehmen soll (“How sculpture should be photographed”). It becomes necessary to second the intentions of the sculptor, which is why the photographer must irrevocably get his shot by positioning himself in such a way as to capture the main point of view that the artist has conceived for his work(Hauptansicht, the Swiss scholar called it, and for classical statuary it was always a Vorderansicht, or frontal view): to go outside this logic implies, for Wölfflin, a misrepresentation of the author’s will. After all, to photograph sculpture is to reduce into two dimensions what is born three-dimensional. Pignatelli therefore starts with a photograph of an ancient work (almost always taken by others) and reproduces it on his supports, which are often nothing more than industrial waste (or in any case capable of evoking the remnants of the production of factories and construction sites) and even scraps of demolished buildings, “all melancholically marked by traces of a past of sometimes even glorious functionality,” as Natali rightly notes, and on which time and chance take, or have already taken, their course: iron corroding, dirt settling, tarpaulins torn, metals burned. Materials that industrial society abandons but to which new life is bestowed and which, therefore, change their function: “we can only be what we do not throw away,” Massimo Bertozzi chides. All this, of course, under the tight control of the artist, a metaphor for the man who nonetheless manages, perhaps with difficulty or amid various sufferings, to govern chance.

Similarly, the examples of Alberto Burri, Robert Rauschenberg (and his black paintings), Mimmo Rotella, and all those artists who, from the 1950s onward, would let time, matter, randomness, and external agents play a leading role in the creation of works: it is to such artists that one thinks when one looks at Pignatelli’s large black panels, specially made for the exhibition at Palazzo Cucchiari, on which riddles of symbols thicken, mostly invented by the Milanese artist’s flair, formed by tar inserts, another material copiously used. One almost seems to glimpse the outlines of those airplanes that often return in Pignatelli’s production, or even picture frames, work tools, tree trunks, which seem to emerge from the black background against which their silhouettes are silhouetted, only to perhaps plunge back into the darkness from which they came: this sense of suspension, of the indefinite, and even, if you will, of looming, is entirely inherent in that reflection on history and memory that underpins the refined philosophical framework of Luca Pignatelli’s work.

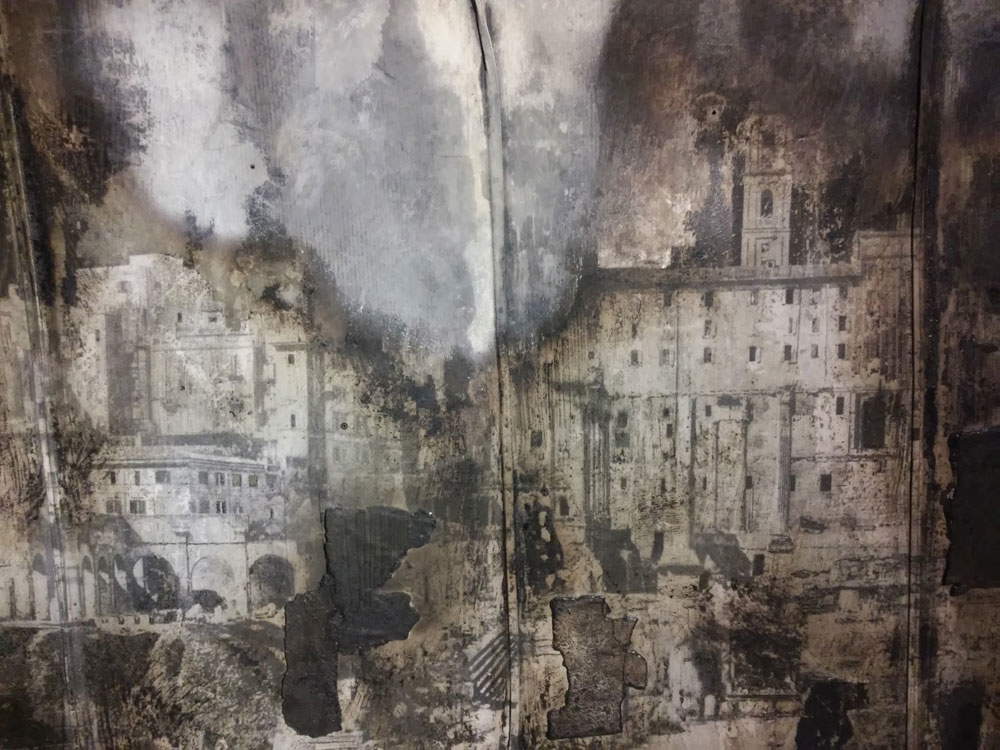

An incumbency that we find again in the views of Rome, fragments of the Urbe also furrowed by gloomy mists that partly conceal squares, buildings and monuments, and partly force us, again, to come to terms with transience, with the deforming action of the passage of time, and over which, like menacing clouds, heavy iron panels always hang. Pignatelli seems particularly fascinated by the ruins of ancient Rome: he has made no secret of the fact that “painting” ruins has a high moral and philosophical value for him, which becomes almost spiritual. And it is not complicated to understand the reason for this: a building, when it becomes a ruin, is cloaked in a renewed grandeur: all the great artists of the eighteenth century, following the rediscovery of Paestum, Herculaneum, and Pompeii (the latter city, to which Pignatelli has moreover dedicated a work) rushed to Campania to admire the vestiges of the resurfaced past. Pignatelli’s approach is not dissimilar to that of a Giovanni Battista Piranesi (another reference point of considerable importance) who is moved by the ruins and, unlike a Winckelmann, in front of the remains of antiquity ends up feeling strong emotions from which his famous, grandiose views, or the sinister plates with imaginary prisons will later be born. Ruins that, of course, belong to a distant past, but also to a much closer past: what else are those discarded materials of which we have long spoken (or those airplanes and old locomotives, which although absent from the Carrara exhibition appear in much of Pignatelli’s production), if not ruins closer to us?

|

| The room with views of Rome |

|

| Luca Pignatelli, Rome (2016; mixed media on galvanized iron, 277 x 208 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| Luca Pignatelli, Rome (2016; mixed media on galvanized iron, 370 x 293 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| Luca Pignatelli, Rome, detail |

|

| Luca Pignatelli’s “black paintings” |

In the panorama of contemporary figurative art, Luca Pignatelli is certainly one of the most acculturated and original artists, capable of expressing his imagery to the fullest in both small-format and larger works, and who knows how to get his reflections on history across to the viewer in a timely manner: the elegant sobriety of Palazzo Cucchiari does the rest, presenting itself as a particularly suitable venue to bring out the message that Pignatelli intends to address to the public, if only because of the alternating fortunes that this nineteenth-century mansion has experienced over the years. It is a strong message that makes use of a powerful and evocative figurative repertoire that happily blends the ancient and the contemporary, that mixes the action of nature (and that of man) with references to the greats of the past, that finds its own peculiar originality in these mixtures, new yes, but the result of a long tradition, and in the way the artist expresses them.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.