Cannibal. At times he had apostrophized himself thus, Pablo Picasso, with lucid consciousness of his own carnal experimentation in continuous search for ever new forms, for unprecedented materials, with an unmistakable stylistic signature that made him recognized as the undisputed genius of 20th century art. “Nothing is created, nothing is destroyed, everything is transformed”: the physical law of conservation of mass could be applied to his art. Art remade on art. Themes and motifs of art history devoured by the Picassian gesture.

History and myth of a complex man and artist who deconstructed the conventional rules of artistic representation come alive in the exhibition Celebrating Picasso. Masterpieces from the Kunstmuseum Pablo Picasso in Münster, curated by Markus Müller, director of the museum, through May 4 in the Sale Duca di Montalto of the Royal Palace in Palermo. The exhibition, organized by the Fondazione Federico II, in collaboration with the museum in Münster, of which Olivier Widmaier Picasso, son of Maya Picasso and grandson of the master, is president, presents 84 works, including lithographs, linocuts, aquatints, etchings, ceramics, puntesecche, along with three paintings, with loans also from the Picasso Museum in Antibes, the Mart in Trento and Rovereto, the Galleria La Nuova Pesa in Rome, as well as loans from private collections (catalog published by the Fondazione Federico II). Works capable of recounting the profound autobiographical imprint of an art of which he himself said, “The work one paints is a kind of diary to be kept.”

Like a kind of photographic diary is the spatial “box” carved out in the first exhibition room, with a series of photographs taken by David Douglas Duncan, the Spaniard’s principal photographer, who in 1956 granted him total access to his studio and living spaces.

Moving on to the overall view of the next large room with the works gives at first glance an impression of a “string of paintings,” which gives the exhibit a minimalist, purely retro feel. But it is by approaching the display counterwalls that the lighting, which is perfect, manages to create breaks of isolation between one work and the next, allowing their best appreciation.

Only, for the rare landscape painting in the exhibition, Landscape of Vallauris (1958, oil on canvas, private collection), we would have preferred other solution of distancing the audience to the more obvious glass placed to shelter it. If only to highlight even more the highlights of the exhibition displayed in the center of the back wall: this and the Seated Fisherman with Cap (Nov. 3, 1946, oil on plywood, Musée Picasso, Antibes, gift of the artist in 1946).

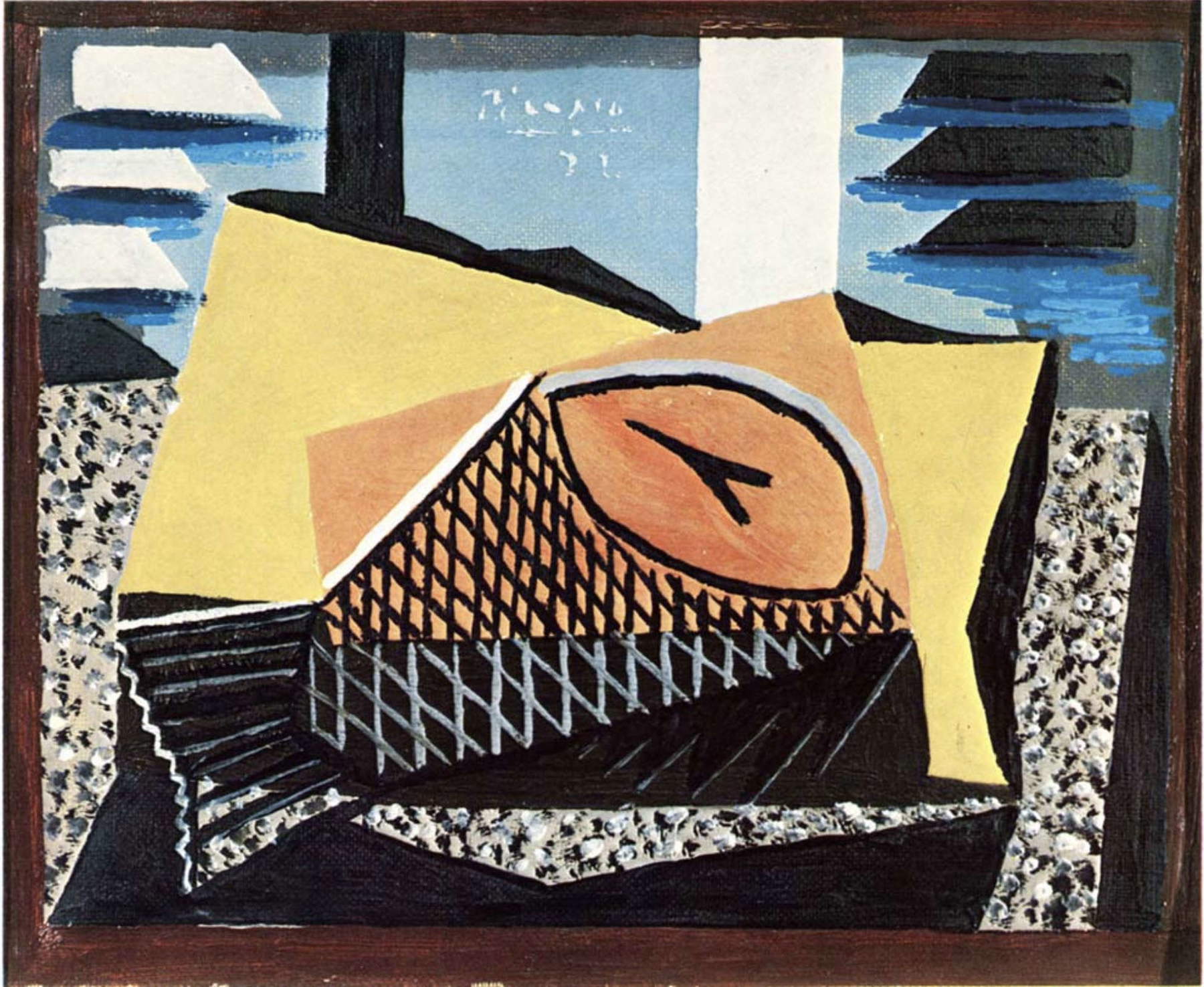

Of the landscape, in which green and blue dominate, the surface planes elude traditional perspective by interpenetrating one another in a dynamic interplay. The Fisherman, an example of what is called the “Picasso Style” that characterizes the master’s work of the late 1930s, combines multiple Cubist views and Surrealist metamorphoses with the use of abbreviated rendering of facial details, using boat paint and a plywood panel. A key trait is the simplicity and essentiality of the representation. As in other works, the Spaniard entrusts the attitude of the body, and not the face, with the expression of the state of mind, which here, reconnecting with what has been said above about his relationship with the iconographic tradition, is rendered with the reinterpretation of the classical representation of melancholy: a “melancholy sailor,” I would call him precisely, with his head resting on his hand and his other arm released on his leg, as in Albrecht Dürer’s famous Melencolia I, but also, to mention painters close to him, in Vincent van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr. Gachet (1890) or again in the various depictions of Melancholy made by Edvard Munch between 1891 and 1896.

An iconic image chosen for the exhibition is the Small Crowned Woman’s Head with Flowers (Color linocut, proof, third and final state; permanent loan from Sparkasse Münsterland ost to Kunstmuseum Pablo Picasso Münster), executed with the technique of linocut, which offered the artist the unique opportunity to create “painting by engraving,” whereby colored surfaces are combined with the precision of line drawing. In this case the predominant color aspect are browns, as well as in Head of a Woman with Hat/Landscape with Bathers (March 8, 1962, color linocut, 2nd of 3 stages; permanent loan from Sparkasse) in Jacqueline with Headband (Feb. 13, 1962, color linocut, proof, 1st of 3 stages; permanent loan from Sparkasse). In this technique the Spaniard also produced a poster for bullfighting. Of the latter, an existential metaphor for his own art, he said, “Imagine for a moment that you are in the center of the arena. You have your easel and your canvas, it is blank and must be painted and everyone is watching you. [...] The slightest mistake and you are dead. And you don’t even need a bull to do it.” The theme of bullfighting is represented in the exhibition through several aquatints and linocuts, including To the Bulls (Plate 2 of Bullfighting, 1957-1959, aquatint; Kunstmuseum Pablo Picasso Münster - Huizinga collection), Picador and bullfighter waiting for the “paseo de cuadrillas” (Sept. 8, 1959, color linocut, proof, second and last state,

permanent loan from Sparkasse), Bullfighting in Vallauris 1960 (July 13, 1960, color linocut, permanent loan from Sparkasse).

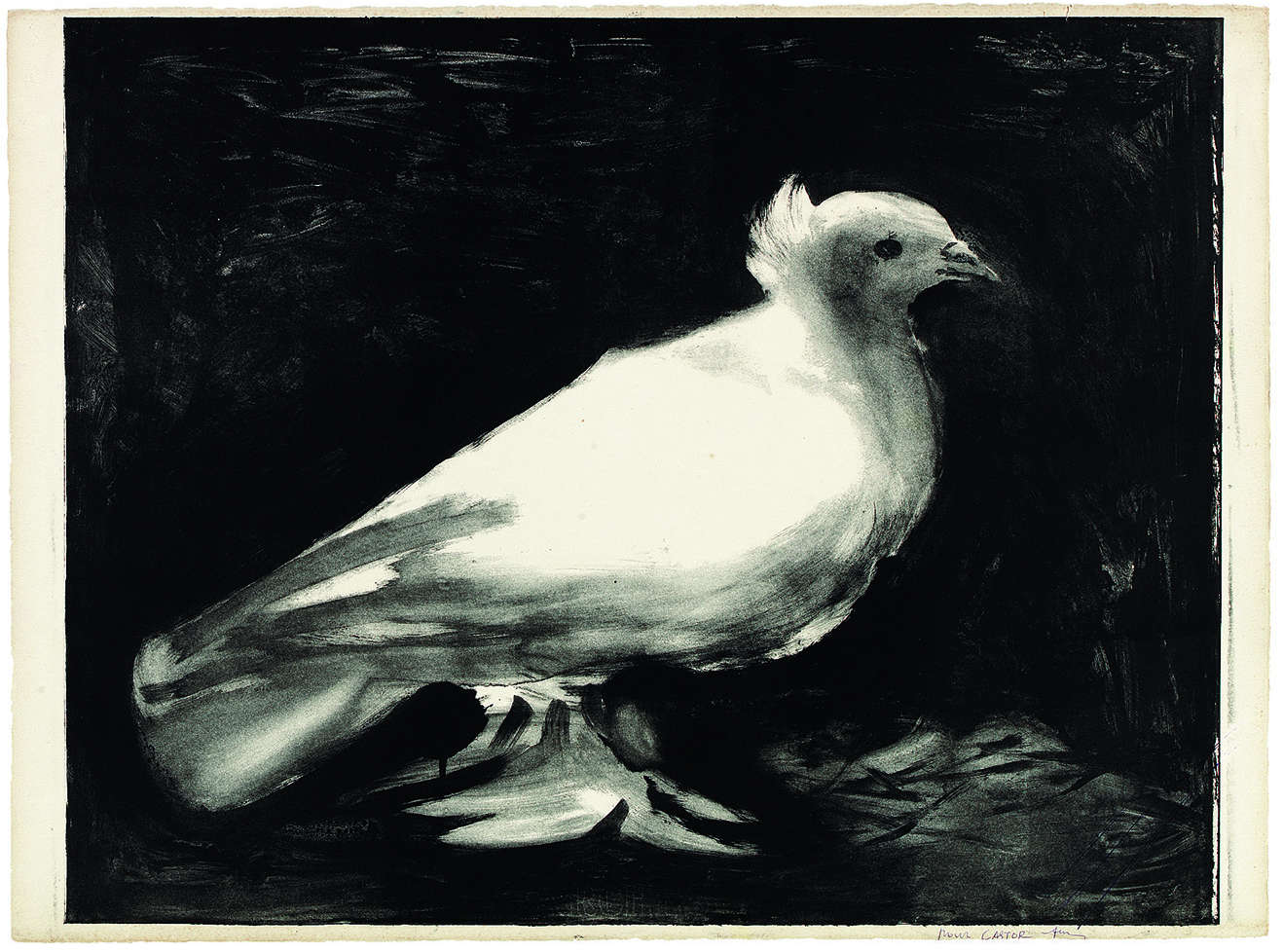

An equally iconic role, also reproduced on the floor that greets visitors at the entrance, is assigned to the famous “dove,” which the Spaniard interpreted in ever-changing variants beginning with that first lithograph, featured in the exhibition, made on January 9, 1949 to be posted in Paris in April of that year at the Congress of Intellectuals for Peace. It became a globally recognized symbol of peace, according to the iconography created by Picasso himself. In the spring of 1949, Picasso’s partner Françoise Gilot, after their son Claude born in 1947, gave the artist a second daughter who was named Paloma (Spanish for “dove”).

Among the most interesting works in the exhibition is a lithograph depicting the little girl in the act of almost proudly displaying her doll Paloma and her doll, black background, Dec. 14, 1952

lithograph (chalk, scraper on zinc), last of four proofs with reduced margins before the edition, signed in red chalk: “Bon à tirer Picasso.” “It is a difficult feat,” Müller writes in the catalog, “to motivate a small child to sit like a model and be still. According to contemporary witnesses, Picasso used the trick of making children believe that he did not want to portray them, but their stuffed animals or dolls. This also explains little Paloma’s ostensive attitude.” There is also a portrait of Paloma juxtaposed by contrast with that of her brother: black lines on a white background for the little girl, inverted two-tone for Claude(Paloma and Claude, April 16, 1950, lithograph (hand drawing [with ink] on transfer paper, reprinted on stone).

In this well-representative survey of the Picassian universe, one feels perhaps only the absence of some figures typical of the artist’s repertoire, such as melancholy harlequins and circus characters. Absence more than balanced, in the large central space of the room, by the marvelous ceramics created after World War II in Vallauris, southern France, including the splendid rectangular plate with the Three Sardines, white earthenware, engobed decoration, knife engraving under yellow glaze (no. 98/200; Kunstmuseum Pablo Picasso Münster, Classen collection) and the one with the Shining Dove (1953, ceramic, rectangular dish, Nicola Pontalti collection, Trento), the Owl pitcher (1954, turned pitcher, white earthenware, oxide decoration on white glaze, 500 examples produced; Kunstmuseum Pablo Picasso Münster, Classen collection), the one with The Bearded Woman (1953, ceramic, turned jug; Nicola Pontalti collection, Trento). Or, again, Jacqueline at the Easel (1956, ceramic, round plate, Nicola Pontalti collection, Trento) a true translation into ceramics of a work between Cubist and Surrealist, which makes it clear that Picasso was faithful to his stylistic autonomy regardless of the material and object with which he tried his hand.

The author of this article: Silvia Mazza

Storica dell’arte e giornalista, scrive su “Il Giornale dell’Arte”, “Il Giornale dell’Architettura” e “The Art Newspaper”. Le sue inchieste sono state citate dal “Corriere della Sera” e dal compianto Folco Quilici nel suo ultimo libro Tutt'attorno la Sicilia: Un'avventura di mare (Utet, Torino 2017). Come opinionista specializzata interviene spesso sulla stampa siciliana (“Gazzetta del Sud”, “Il Giornale di Sicilia”, “La Sicilia”, etc.). Dal 2006 al 2012 è stata corrispondente per il quotidiano “America Oggi” (New Jersey), titolare della rubrica di “Arte e Cultura” del magazine domenicale “Oggi 7”. Con un diploma di Specializzazione in Storia dell’Arte Medievale e Moderna, ha una formazione specifica nel campo della conservazione del patrimonio culturale (Carta del Rischio).Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.