Already after the first rooms of the Macchiaioli exhibition in Pisa, the public will be able to breathe a sigh of relief: at last an exhibition on the subject that does not disappoint expectations. And yes, it should perhaps be clear from the title that the one set up at Palazzo Blu is a high-profile exhibition: I Macchiaioli. Period. Without subtitles, without embellishments, without frills, firmly and authoritatively, without trying to entice the visitor. And one feels satisfaction because unfortunately, for some time now, every time news of an exhibition on the Macchiaioli arrives, it is necessary to lower the level of expectations. In a society that is increasingly liquid, insecure and irresolute, there seems to be only one certainty left: that at least once a year, somewhere in Italy, an exhibition on the Macchiaioli will be organized. One has lost count of the number of exhibitions on the Macchiaioli that, often with less than memorable outcomes, have been set up in various museums. In the last three years (and in between there has also been a pandemic!) there have been exhibitions on the Macchiaioli at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Milan, the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Turin, Palazzo Zabarella in Padua, Palazzo Mazzetti in Asti, Palazzo delle Paure in Lecco, and the Forte di Bard (and we are probably forgetting a few), to which must be added monographs on individual artists. The reason for such a success is easily said: the Macchiaioli are associated by many with the Impressionists, another name that is a guarantee of success when one wants to order an exhibition that is easy on the public, and the size of the group, in addition to the length of their experience and the prolificacy of many of them, facilitates the task of the curators who, year after year, have worked hard to put together selections that are often anything but exciting.

Not that there has been a shortage of interesting opportunities for in-depth study (e.g., on collecting nuclei, or on single episodes: among the most worthy initiatives it will be worth mentioning at least the one on the unpublished works of Silvestro Lega held in 2015 at the Matteucci Institute in Viareggio, or the one on the ties between Signorini father and son in Florence in 2019), but there have also been exhibitions that, with somewhat picky selections and substantially lacking in fundamental works, have claimed to reconstruct the history of the movement. At Palazzo Blu, the curator, Francesca Dini, has instead chosen a different paradigm: to concentrate the reasoning above all on the group’s origins by gathering works of undisputed quality, including many fundamental masterpieces (and for those absent from the exhibition, for example Silvestro Lega’s Pergolato or Telemaco Signorini’s L’alzaia, there is the catalog that makes up for it: the absences, therefore, are few). And to offer the public a history of the movement outlined in its fundamental moments, without neglecting the premises: it even begins with the history painting practiced by the future Macchiaioli (who, before adopting the name by which they would go down in history, presented themselves as the “progressists”), with works that are not always given to see in reviews that also aim to provide the public with a complete overview of the group’s events.

And indeed, the Palazzo Blu exhibition gives the impression of orienting itself along a precise direction: bringing order to the exhibition turmoil that has been accompanying the name of the Macchiaioli for some time now, clarifying some aspects of their work that are often cited out of hand (think of the relationship these artists had with the Risorgimento), providing further food for thought (for example, their connection with Pisa, on which Cinzia Maria Sicca’s essay focuses in the catalog), introducing some historical novelties (in particular on Signorini in Riomaggiore: unpublished documentary material was found, screened by Elvira D’Amicone), and limiting it to artists of the first generation. Thus, the various Francesco Gioli, Niccolò Cannicci, Eugenio Cecconi, Angelo Torchi, Adolfo and Angiolo Tommasi are left out: a pity, because perhaps at least Gioli could have been included in the itinerary, because of his role as a promoter of the movement, his close ties with the Pisan territory, and his relations with Martelli and Castiglioncello.

Set-ups of the

Set-ups of the Set-ups of the exhibition I

Set-ups of the exhibition I Set-ups of the exhibition I

Set-ups of the exhibition I Set-ups of the exhibition I

Set-ups of the exhibition I Set-ups of the exhibition I

Set-ups of the exhibition I Set-ups of the exhibition

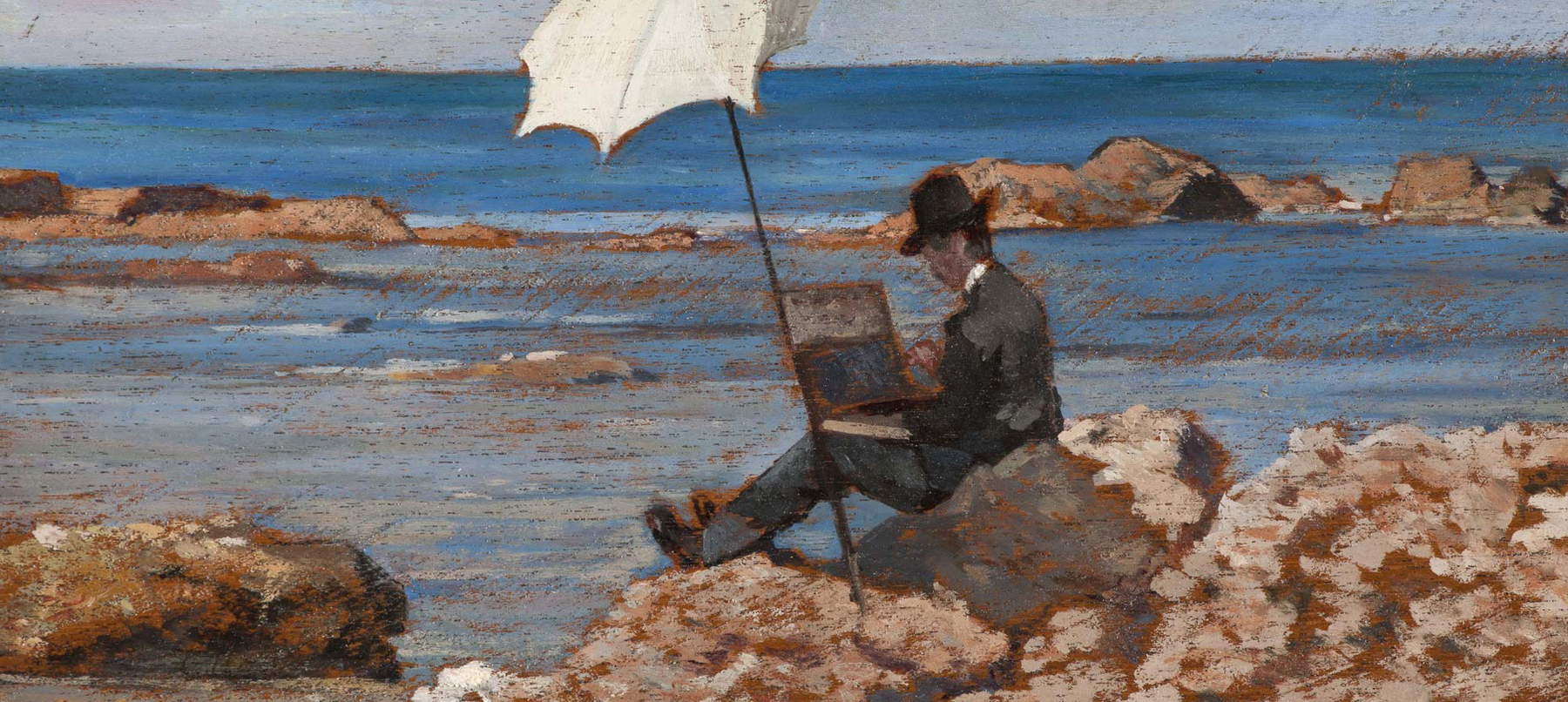

Set-ups of the exhibitionThe tour itinerary starts with a strikingoverture: Giovanni Fattori’s Silvestro Lega painting on the rocks, a work from a private collection that is nonetheless among the group’s most famous, introduces the exhibition, revealing from the outset both the Macchiaioli’s aptitudes (and in particular their predilection for en plein air work) and their radical technical innovations, since Fattori’s tablet, which is from 1866 and thus belongs to the season of the Leghorn painter’s most extreme experimentalism, is one of the purest examples of macchia painting. But that’s not all: it was also chosen as a proem to emphasize the way these artists used to work, namely alone or in small groups that traveled the countryside and coasts of Tuscany in constant search of new views to fix with their brushes. Having thus introduced d’emblée some new elements with which the Macchiaioli renewed Italian painting, we move on to the premises that would lead to the birth of the group: the exhibition invariably leads us to the Caffè Michelangelo in Florence, the usual meeting place of a group of young people who were moved by the desire to modernize history painting, attracted by the ideas of the Frenchman Paul Delaroche, who preferred more intimate episodes to the rhetorical celebration of the most high-sounding historical facts, but to be told in more intense dramatic tones. The first to move in this direction were Cristiano Banti, who in one of his first attempts in 1848 recounts the anecdotal episode of the landowner Beccafumi discovering the son of one of his sharecroppers, Domenico known as “Mecherino,” intent on drawing perfect sheep on the land (the little one would later become one of the greatest painters of the 16th century: Domenico Beccafumi), and who even more emphatically, in 1857, will try to imagine Galileo before the tribunal of the Inquisition, and Silvestro Lega who again in 1859 painted the famous scene with Titian and Irene of Spilimbergo. Also featured in the exhibition are Saverio Altamura’s Buondelmonte’s Funerali di Buondelmonte to introduce the figure of the Foggiano who was first among the innovators of history painting and helped spread the ideas of the Neapolitan Domenico Morelli to Florence (there are no paintings of his in the exhibition, however), and later later, in 1855, he was to go with Morelli himself and the Leghorn-born Serafino De Tivoli to the International Exhibition in Paris, a fact that historiography now recognizes as the basis of the group’s birth, set by many scholars to that fateful year when the young people of the Caffè Michelangelo found themselves discussing ideas imported from France.

It is in the second room that the figure of Serafino De Tivoli is explored. Unfortunately, the Palazzo Blu exhibition does not allow space for the other exponents of the Staggia School, that group of painters (among whom at least Lorenzo Gelati and Carlo Markò the younger should be mentioned) who, following the example of the Barbizon School, roamed the Sienese countryside to paint the landscape in the open air: their pioneering research on the veduta, represented in the exhibition by a pair of landscapes by Serafino De Tivoli, one pre- and one post-1855, had, on the one hand, the misfortune of not being sufficiently understood, and on the other that of being swept away by the 1855 Exposition that sanctioned the affirmation of landscape painting and accelerated the investigations of the Macchiaioli (the period between 1856 and 1859, and the first sorties of Telemaco Signorini and Vincenzo Cabianca in Venice and on the Ligurian Levant, can be traced back to the first evidence on macchia painting). The exhibition, however, recognizes the fundamental role of De Tivoli as well as that of another undisputed pioneer, the inventor of the modern Italian landscape, that Nino Costa who was a great friend of Fattori’s and who is present in the exhibition with a fundamental painting, the Donne che imbarcano legna al porto di Anzio, which we can consider the first modern landscape in the history of Italian painting, animated as it is by a new idea of the view, since it is attentive to the most humble and everyday situations and which previous landscape painting would never have taken into consideration, and above all since it is capable of making the glimpse of the Latium coast resonate in unison with the painter’s feeling, well in advance of the paysage-état d’âme researches of late 19th century European painting.

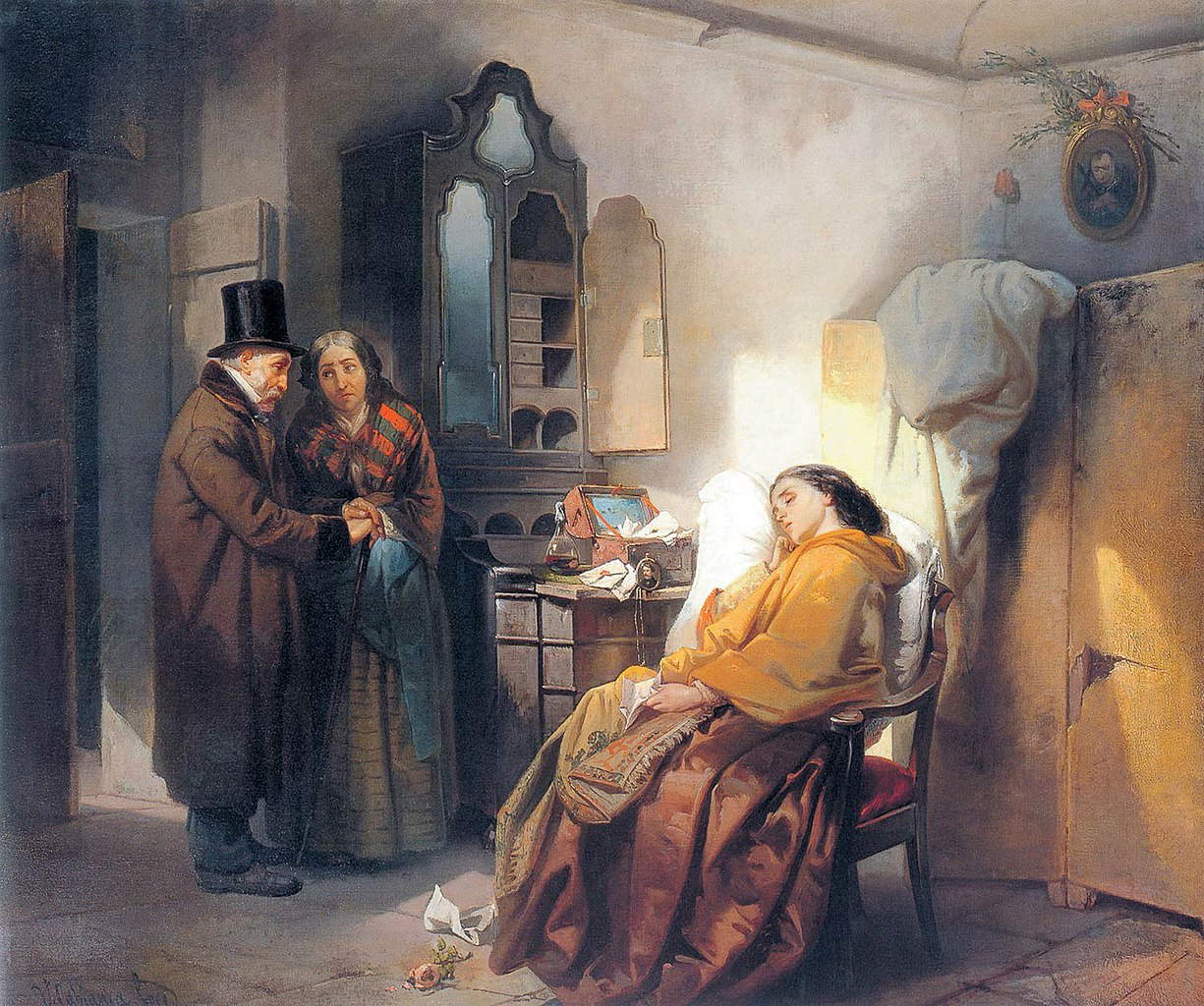

The following section is an initial lunge on the Cabianca-Signorini partnership: with surgical precision, the review traces the origins of macchia to the research of the Veronese and the Florentine (as has long been known to Macchiaioli studies, but as often does not appear by visiting many exhibitions), represented in the room by some paintings that can be counted among the embryos of macchia painting. These include the Wedding at Chioggia, which, despite its innovative hint of synthesis, does not abandon the sense of the picturesque typical of northern Italian painting (the crowding of figures busying themselves with their daily tasks, the riot of sails, certain unusual and bizarre poses, some rhetorical elements such as the sailor turning toward the viewer), and theAbandoned, a painting “resolved in the beam of light that invests the female figure and takes on the task of expressing her’human suffering,” as the curator writes in the catalog. The research conducted for the exhibition, moreover, made it possible to clarify the subject of this painting, which is taken from a poem by Giovanni Prati from 1841, theEdmenegarda: a piece of literature where, however, Dini still emphasizes, “the reference to contemporary reality is so resounding and evident in the eyes of his companions as to mark a very precise direction of research, that toward contemporaneity.”

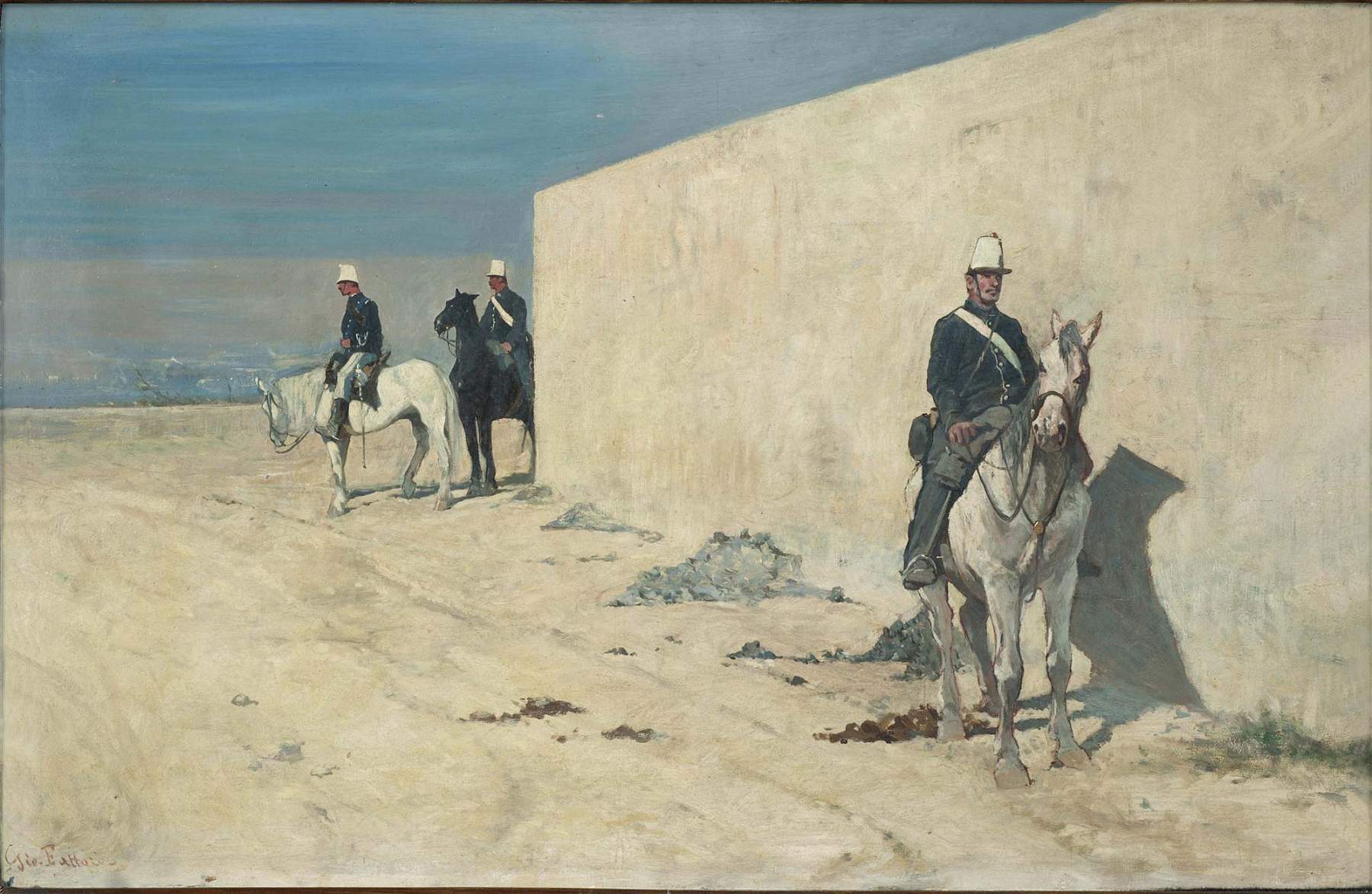

And contemporaneity enters the exhibition with impact with the room devoted to the Risorgimento. Unlike the vast majority of exhibitions on the Macchiaioli, the insistence on Risorgimento themes, at Palazzo Blu, is very limited. That is, just enough to clarify the role these painters played in the events that would mark the history of Italy. And if the Macchiaioli have often been seen, wrongly, as passive singers of the Risorgimento (the misunderstanding probably stems from a superficial reading of the great battles by Fattori, who painted them mostly on commission), the Pisa exhibition, while acknowledging that many Macchiaioli, sincere patriots, participated with fervent passion in the events of that time, so much so that several of them enlisted to take part in the wars of independence, and there were even those who left their lives (this is the case of Raffaello Sernesi, wounded in the battle of Condino in 1866 and died at the age of only 28: in any case, Cosimo Ceccuti’s essay in the catalog reconstructs the individual vicissitudes of each of the Macchiaioli engaged in the wars), at the same time making it clear that they did not lend their art to celebratory emphasis. There is no rhetoric, then, but if anything, much attention to the human aspects of the conflict: the solidarity between Italians and French in Signorini’sTuscan Artillery at Montechiaro, the respectful silence of the soldiers advancing among the fallen in Fattori’s celebrated Italian Camp after the Battle of Magenta, the domestic intimacy of Borrani’s women participating in the battles from home, caught offering their contribution by sewing the flags, or the red shirts of Garibaldi’s men. Even Silvestro Lega’s portrait of Garibaldi catches the general with his eyes downcast, in a moment of pensive reflection. Also from Trissino came one of Fattori’s best-known works, In vedetta, which is also one of Fattori’s most daring experiments on the macchia, with the dazzling white of the wall that, in the dazzling light of the summer sun, amplifies the sense of anticipation of the three soldiers on horseback, standing still waiting for something to happen (or perhaps not).

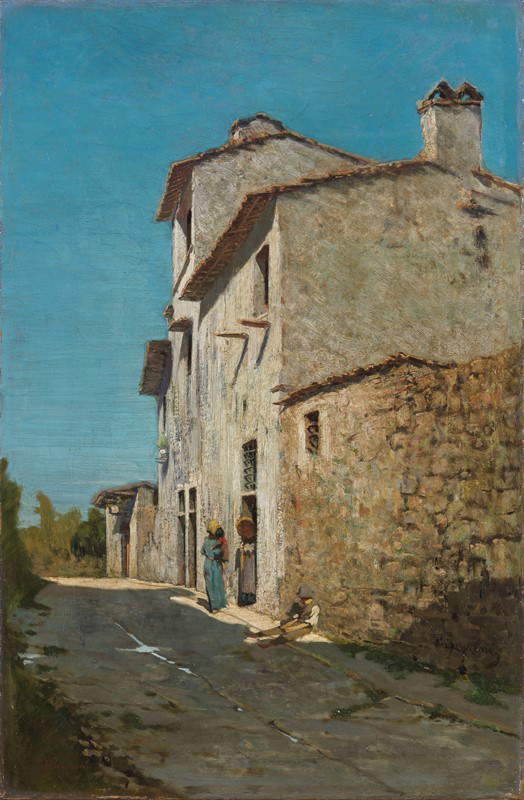

Marriage in Chioggia

It continues with a section devoted to Cabianca’s Mattino, which the artist exhibited in 1861 at the annual exhibition of the Promotrice di Torino, the one from which the name “macchiaioli” originated: this is how they were baptized, in a derogatory tone, by an anonymous reviewer of the Gazzetta del Popolo, who signed himself “Luigi” (later identified in the man of letters Giuseppe Rigutini). The artists of the group, who called themselves the “progressives” and who until then had been called “effectors” by critics, decided to give them that nickname that later passed into history. But that exhibition was also important because it represented the first successful occasion for the movement, a success sanctioned by the purchase of Morning by the Promoter Society, which was organizing the exhibition. It was, moreover, a painting in which the vigorous experimentalism of the previous years was toned down in favor of a quieter search for light effects, capable, however, of bringing the scene to life: “this narrative, however intimate and graceful,” the curator rightly explains, “would not have poetic evidence if the atmospheric light did not pervade it, making it alive and palpitating, restoring oxygen to the sweet faces pale in faith, moving the blades ofgrass, gilding the curbs of the garden, making the clods of the poor vegetable garden walkable; and rhythm it with the sharp scans of light and shadow capable of restoring to us the painter’s feeling and his excitement before the real thing.” After an interlocutory and somewhat redundant room, which gives an account of the turning point that the 1861 exhibition marked for so many of the group’s painters (Cristiano Banti’s Riunione di contadine, on loan from the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Palazzo Pitti, stands out in particular, another masterpiece in which the effects of crepuscular light are the protagonists), the Palazzo Blu exhibition jumps back in time to deal with the fundamental first season of Cabianca and Signorini’s experiments, following them as they wandered around the Apuan Riviera and the Gulf of Poets. Signorini’s Acquaiole and Cabianca’s Donne alla Spezia belong to those years of tireless research: the two artists attempt to capture now a ray of sunlight coming through an archway (see Cabianca’s Avanzi della chiesa di San Pietro a Portovenere ), now a figure against the light (like the one under the archway in Signorini’s painting), now the full light of noon, or the one that makes the stones of an ancient building stand out (here is Cabianca’s painting of the interior of the walls of the Castle of San Giorgio in La Spezia, exhibited together with his sketch), up to the glow of the marble blocks that Cabianca paints on the beach of Marina di Carrara in a painting with a horizontal format, one of the most interesting masterpieces of the exhibition, not least because of the backlight effect on the figures of the two protagonists (two “buscaiol,” or workers devoted to a very tiring activity: loading marble slabs onto the sailing ships leaving Marina di Carrara) would be taken up by Signorini in his Alzaia always with the same intent, namely to emphasize the extreme heaviness of the work to which so many at that time were forced. The same room also contains works dating from after 1861: the public will be fascinated by Signorini’s Marina a Viareggio, a painting with an almost romantic feel, where a lone passerby stands out against the uniform surfaces of the beach and the sky obscured by clouds that also cover the Apuan Alps on the horizon, and by a large-format canvas, After the Storm by Luigi Bechi, which will nevertheless appear stiffer than the works of his colleagues.

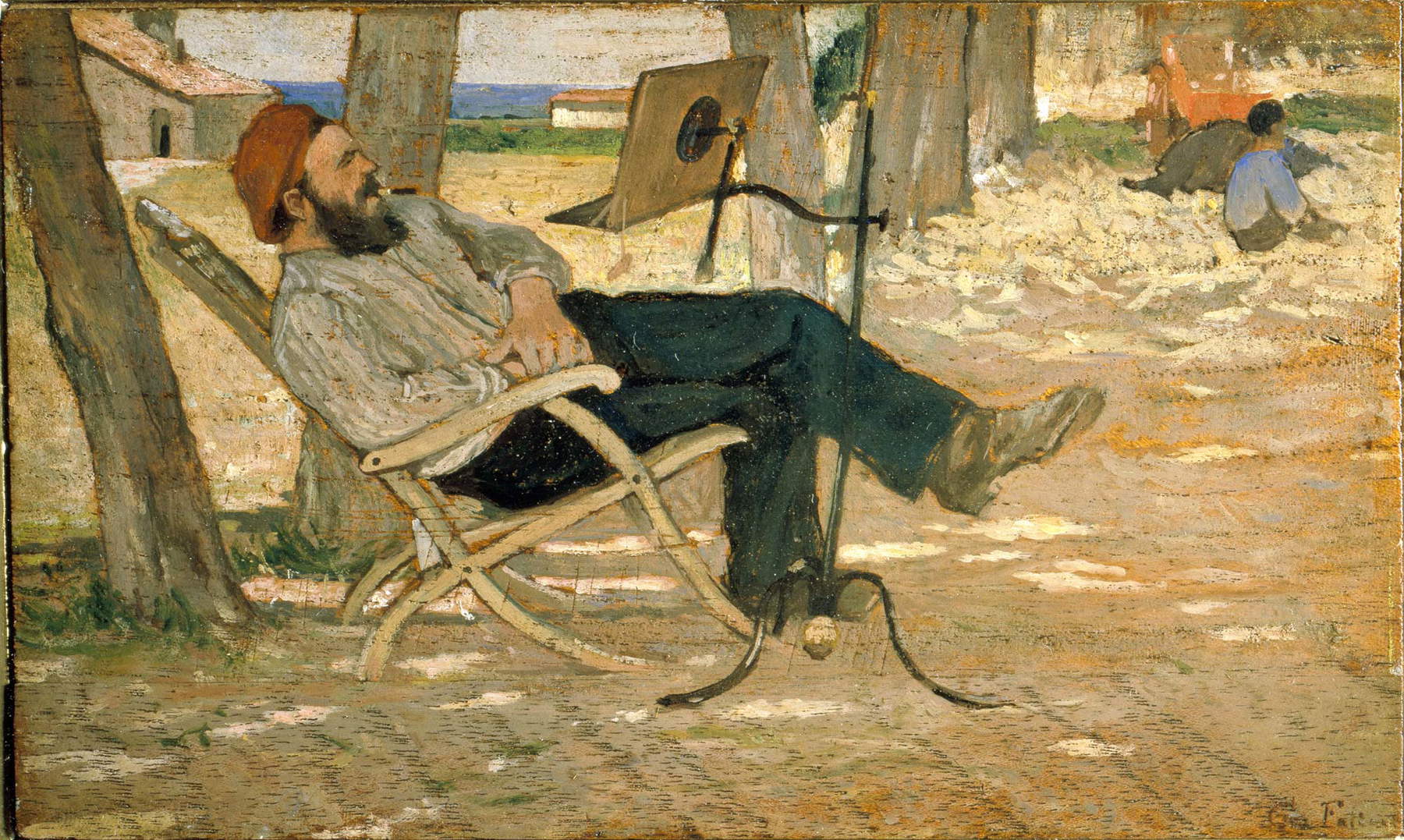

The visit to the first floor continues with two rooms devoted to what Dario Durbè called the “Castiglioncello School.” we are thus introduced to the figure of Diego Martelli, a leading critic of the Macchiaioli group, who after the death of his father Carlo in 1861 inherited a vast estate in the pine forests of Castiglioncello, which became a habitual meeting place for the painters of the group, who were often invited by Martelli (his famous portrait painted by Fattori is on display) to spend time in his villa. A lively community was thus formed, giving rise to one of the most singular experiences in the history of the Macchiaioli: it gave rise, writes the curator, to “small masterpieces capable of evoking the vastness of spaces, the freedom of breath that the artist feels when faced with nature, no longer a nature felt in its immanence, but experienced intimately, subtly investigated by means of the harmonizing principles of drawing and atmospheric light.” Above all, Giovanni Fattori, Odoardo Borrani and Giuseppe Abbati are the protagonists of this season: the exhibition at Palazzo Blu aligns a series of evocative landscapes painted mostly on horizontal panels that recalled the predellas of Renaissance altarpieces, and on which essential views take shape, introducing the viewer to a life with a slow rhythm among the Tuscan countryside, amid oxen grazing on the shores of the sea, in a threshing floor with clothes laid out, at the edge of a pine forest, in a field where peasant women are engaged in their harvesting activities. However, it is also the section on which the exhibition dwells the most, perhaps too much, risking making tired visitors arrive on the upper floor, where the story of the Macchiaioli continues.

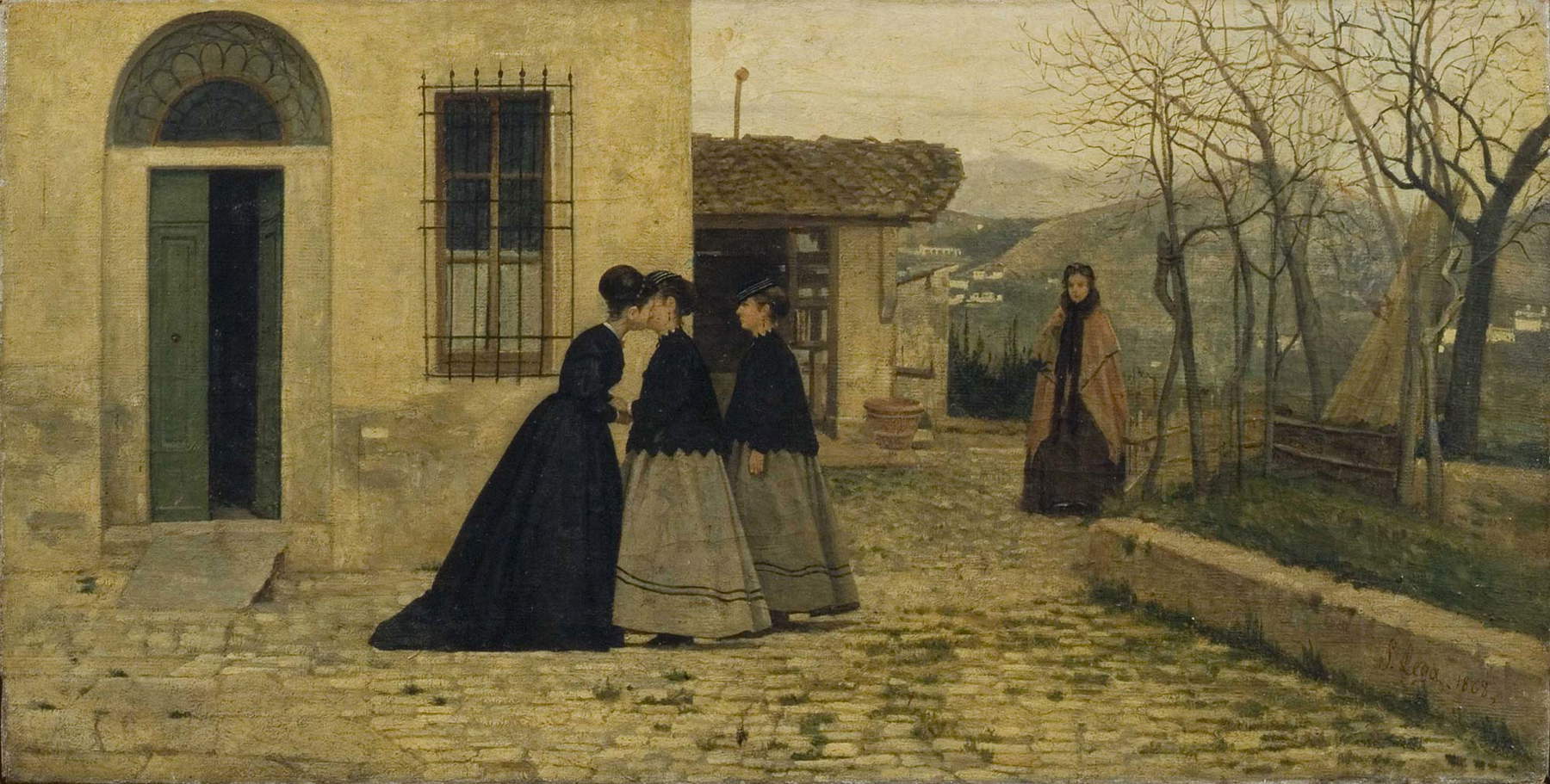

The first room one encounters acts as a counterbalance to the one one has just visited: if Castiglioncello was the meeting place of many of the Macchiaioli on the coast of Tuscany in the summer, in winter many of the group found it more convenient to reach the countryside of Piagentina, a suburb of Florence now urbanized but at that time still able to offer views of rare beauty: evidence of this is the sunset over the fields that Silvestro Lega captures in I fidanzati on loan from the Science Museum in Milan, or Telemaco Signorini’s splendid view of the Arno. However, the Piagentina season differs from that of Castiglioncello in that, in the surroundings of Florence, the Macchiaioli also liked to focus on interiors, or on life in villas (it is here that a fundamental work such as Silvestro Lega’s Pergolato, not in the exhibition, was born: however, another first-rate work, La visita che giunge dalla Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Rome, will be on view): Lega himself is the artist who best interpreted the familial intimacy of Florentine homes (seeEducation at Work), but others were not to be outdone, such as Odoardo Borrani, who succeeded to cloak with accents of social denunciation a painting set in one of these interiors, namely L’analfabeta (illiteracy was one of the most heartfelt problems of the time), displayed next to Signorini’s Case a Piagentina, which, in Borrani’s painting, are reproduced hanging on the wall behind the two protagonists.

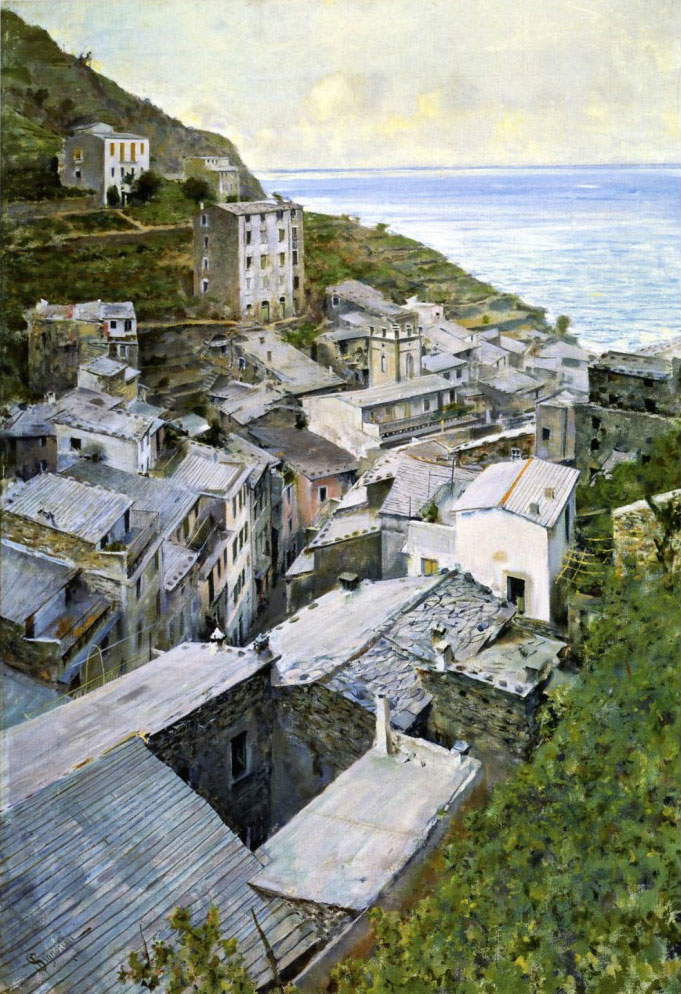

Two sections separate the exhibition from its conclusion: the one dedicated to the Gazzettino delle arti del disegno, the periodical founded in 1867 by Martelli after the closure of the Caffè Michelangelo and which became a new center of the Macchiaioli’s exchanges of ideas in the 1970s, is actually a chapter devoted to Giovanni Boldini in disguise, since the focus is on the young Ferrara artist as he was launched from Martelli’s masthead. Portraits from the very brief Macchiaioli phase of his career are thus on display, compared with those of his master Michele Gordigiani, in perhaps the most ancillary section of the exhibition. The last, on the other hand, is devoted to the research of the 1980s and 1990s, summarized in the last corridor of the upper floor: the younger artists are not presented, however, but we continue with the experiments of the four greats of the first hour, namely Lega, Signorini, Fattori and Cabianca. The former, after tormented personal vicissitudes, continued to find inspiration in a domestic painting of delicate intonations (one example is the touching Lesson of the grandmother), while Signorini was followed in his stays in Riomaggiore in the Cinque Terre, always in search of new solutions that, in Tetti a Riomaggiore, found the form of a daring foreshortening, from the small square overlooking the lower part of the town and giving the impression of a bird’s eye view. As for Fattori, we find in the last part of the exhibition paintings with a war theme that convey all his disillusionment with the lack of social reforms that the patriots who had contributed to building Italy had waited in vain for (and therefore considered themselves betrayed): Pro patria mori, a truculent image of a soldier dead and devoured by pigs, expresses to the utmost the despondency that the painter felt at that time, of which his numerous writings also make us share. Finally, it falls to Cabianca to close the exhibition: in his Mattutino, the painting of macchia is charged with an unexpected spiritual intonation, which almost flows into symbolism and accompanies us “toward the twentieth century,” as per the title of the concluding section.

It has been said that the Macchiaioli have often been juxtaposed with the Impressionists, and it will not be the case here to re-discuss affinities and divergences between the two groups. It will suffice here to repeat what Dini wrote in the catalog, namely that it is misleading to speak of the Macchiaioli as the “Italian Impressionists” because “this entails sacrificing to the reasons of an approximate label (when not even to those of pure cultural marketing) the complexity ideological and cultural complexity underlying the affair of the ’macchia’ by reason of which one can speak of a ’Macchiaioli civilization’ and a renaissance of Italian painting initiated by those artists.” In order to frame the exhibition, however, it is necessary to give in to labels for a moment, and to highlight an element that divides the Impressionists from the Macchiaioli: the fact that for the former there now exists a kind of canon that even the general public is able to remember and recognize, while for the latter this canon struggles to impose itself. That’s it: the Pisa exhibition seems to be moving toward the definition of a rule, and among the rooms of Palazzo Blu we seem to perceive a new fixed point in the already long exhibition history of the Macchiaioli, who owe the beginning of their contemporary fortune to the pioneering exhibition that Palma Bucarelli wanted in 1956 at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Rome. In the catalog an essay, signed by Chiara Stefani, is dedicated precisely to that exhibition, which gathered more than three hundred works at Valle Giulia.

The Pisa exhibition, in spite of its length, which for some may perhaps be exhausting, is smaller in size: one hundred and thirty works distributed over eleven sections, to recount, however, only the vicissitudes of the first generation of the Macchiaioli group, and all supported by a good catalog (which would have been excellent if it had also included worksheets and, above all, a bibliography). Its success, in terms of the breadth and quality of the works exhibited, will have to be measured against some historical reviews: from the aforementioned 1956 exhibition to those in Munich and Florence in 1976, or again the one in Palazzo Zabarella in 2004. It will not be an exaggeration to say that Pisa therefore establishes a new, remarkable stage in the history of exhibitions on the Macchiaioli, a point with which anyone in the future who wants to attempt new operations on the group will necessarily have to measure themselves.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.