by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 10/11/2017

Categories:

Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'The Sixteenth Century in Florence. Modern Mannerism and Counter-Reformation' in Florence, Palazzo Strozzi, from September 21, 2017 to January 21, 2018.

In 1584, playwright and art writer Raffaello Borghini (Florence, 1541 - 1588) published a treatise in the form of a dialogue “in which painting and sculpture are discussed,” and he set it at the “Riposo,” the villa that Bernardo Vecchietti, a patron of artists and a member of one of the oldest Florentine families of nobility, had built just outside Florence as a place of recreation. In the treatise (to which Borghini, juxtaposedly, gave the name Riposo) the task of drawing up the rules that “the painter should be observed” in the invention “of the historie sacre” is delegated to the master of the house: thus, with a modern cataloguing flair, Bernardo Vecchietti lists “three things principally,” namely, strict adherence to sacred texts, the capacity for inventiveness, and the triad composed of “honesty,” “reverence,” and “divotione,” “so that those concerning in exchange for compugnersi a penitenza in rimirare quelle,” that is, the “historie sacre,” “more tosto non si commuovano a lascivia.” Therefore, an artist who wants to propose a painting capable of inspiring pious feelings in the faithful, must not bend to his own whims, is obliged to a strict representation of sacred history and to respect “the holy temple of God” to which the work is destined and, ultimately, has the obligation to offer to the eyes of the observer images that should not be considered improper.

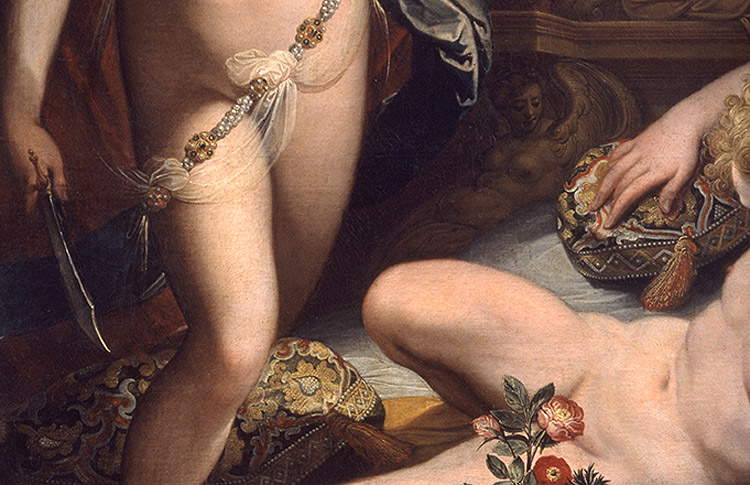

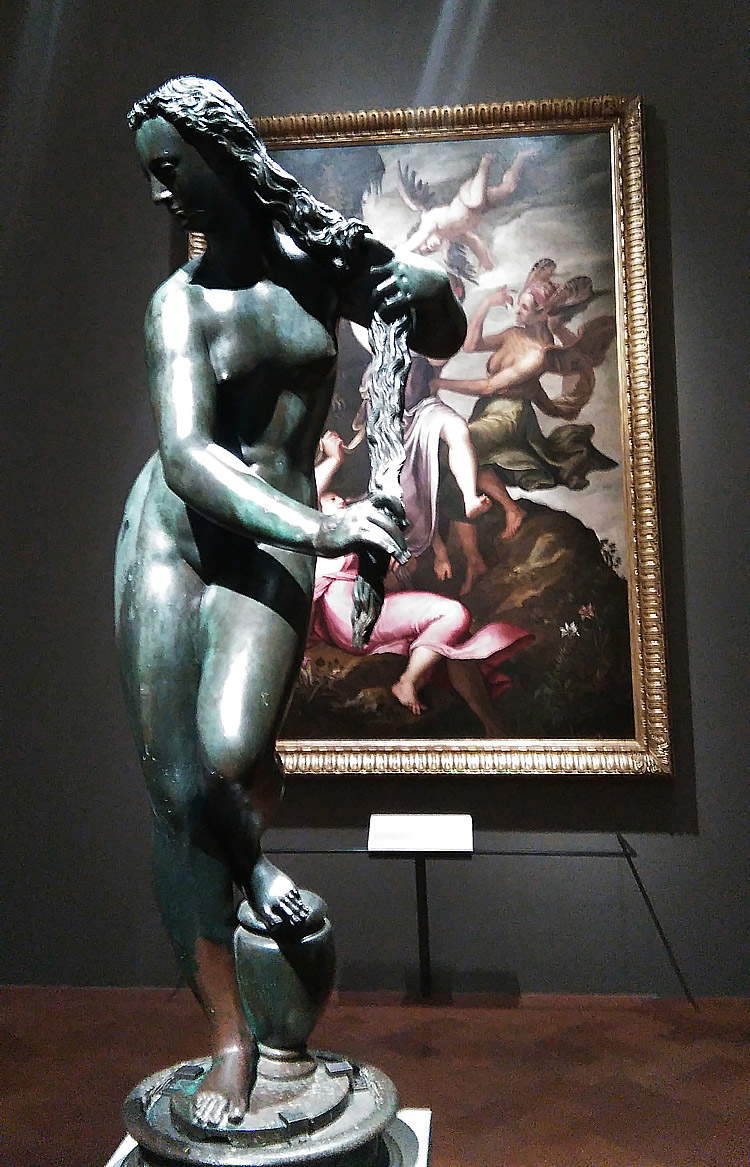

Borghini’s dialogue contains the two concepts around which the exhibition The Sixteenth Century in Florence. Modern Manner and Counter-Reformation: “lasciviousness” and “devotion.” Concepts that the curators, Antonio Natali and Carlo Falciani, would have liked to include in the title of the exhibition currently in the rooms of Palazzo Strozzi. If it is necessary to provide just one of the many keys to interpretation that the highly successful Florentine exhibition offers its audience, one will not struggle to find a kind of constant, which runs from the first to the last room to guide the visitor’s path, precisely in this disagreement between “lasciviousness” and “devotion.” between profane figures cloaked in an eroticism that is at times subtle, at other times blatantly ostentatious, and altar panels steeped in Counter-Reformation rigor, between Venuses rising from the waters smoothing their hair with all-female grace, and chaste Madonnas or redeemed sinners. There is a splendid image, to which Antonio Natali refers in the second of his two essays in the catalog devoted to the importance of Andrea del Sarto for sixteenth-century art in Florence, that more than any other restores with icastic clarity the encounter-clash between “lasciviousness” and “devotion,” and to discover it one must go back to Bernardo Vecchietti’s “Rest.” in the park of the villa, there is a tabernacle that in ancient times had been frescoed with the Gospel episode of the encounter between Christ and the Samaritan woman (painting lost due to the action of time and weathering), and which had been built next to a fountain at the time adorned with a statue of the Fata Morgana by Giambologna (present in the exhibition). The “profane” water of the fountain dedicated to the fairy therefore flowed close to the image of the “sacred” water of the episode in John’s gospel, and similarly side by side were two women, the Samaritan woman of the tabernacle and the lascivious marble Fata Morgana: a sign that, writes Antonio Natali, “in Florence, even in times when one has mostly insisted on humble tones of an austere and rigorous ideology [....], two apparently discordant ways of expression and themes, which not exactly everywhere always knew how to run parallel, coexisted without disquiet.”

|

| Giambologna, Fata Morgana (1572; marble, 99 �? 45 �? 68 cm; Private collection, courtesy of Patricia Wengraf Ltd.) |

The first of these “parallels” between the sacred and the profane comes right at the opening, in the first of the two rooms devoted to the masters: the audience at Palazzo Strozzi is greeted by Michelangelo ’s (Caprese, 1475 - Rome, 1564) river god, to which Andrea del Sarto’s (Andrea dAgnolo, Florence, 1486 - 1530) Pietà of Luco almost acts as a backdrop. A parallel that, it could be said, is twofold, since Michelangelo’s pagan deity, indebted to counterpart works of classical antiquity, was conceived with the purpose of being inserted into a sacred building, the New Sacristy of the Basilica of San Lorenzo in Florence: the models, however, were never translated into marble, since Michelangelo renounced the initial project. Above all, it is a parallel that very effectively anticipates the thematic and stylistic motifs of the second half of the 16th century in Florence: the Pietà of Luco, with the host of the Eucharist exhibited above the chalice to forcefully affirm the doctrine of transubstantiation denied by the Lutherans, is a work that contains the tensions that shook 16th-century society, and the river god, with its dual pagan and Christian nature, is sculpture that is the bearer of all the contradictions of the time. Both, then, were unsurpassed stylistic models for the artists of later generations, and in the exhibition, punctually, one finds works with cues that openly refer to them.

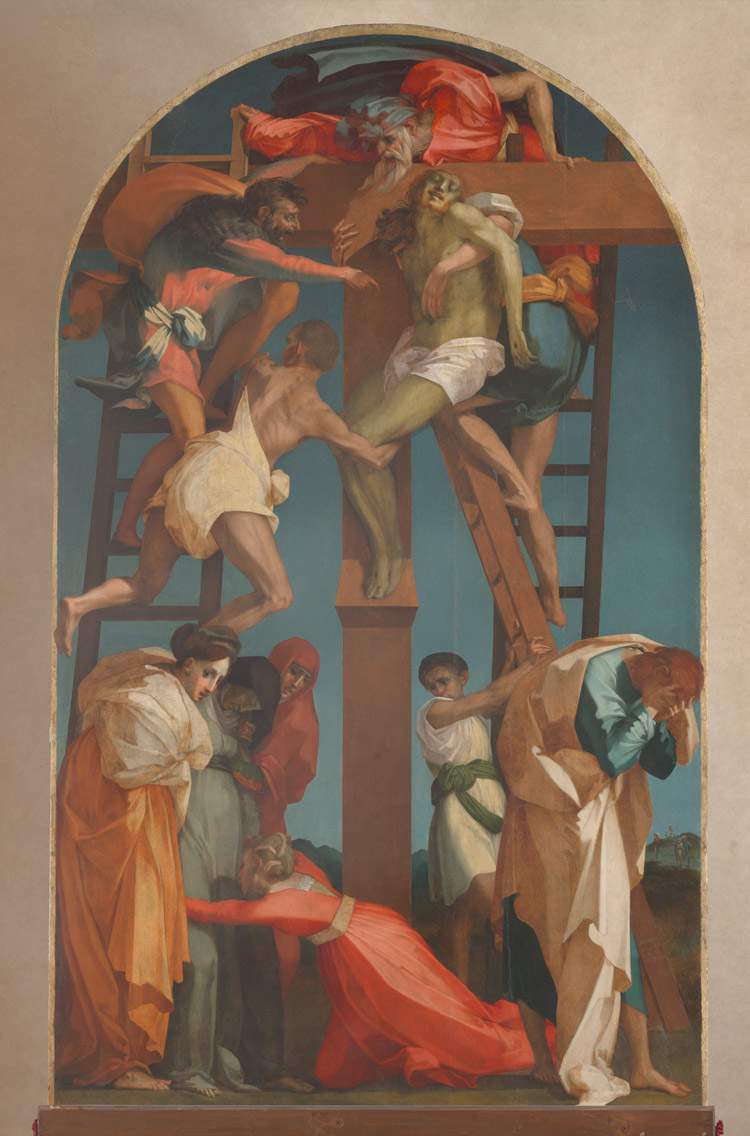

The next room opens to a comparison that we may venture to call unrepeatable: we find in fact close neighbors the Deposition of Rosso Fiorentino (Giovan Battista di Jacopo, Florence, 1494 - Fontainebleau, 1540), that of Pontormo (Jacopo Carucci, Pontorme d’Empoli, 1494 - Florence, 1557) and that of Bronzino (Agnolo di Cosimo, Florence 1503 - 1572), which come respectively from the Pinacoteca Civica in Volterra, the Capponi Chapel in Santa Felicita in Florence and the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Besançon. Three different ways of diverging from the furrow traced by the masters: divergences that, for Rosso and Pontormo, become moreover literal, since they were both direct pupils of Andrea del Sarto. Rosso Fiorentino: a painter whose anti-Classicism is to be found in those metallic draperies, in faces disfigured by almost belligerent grimaces, in a totally nonconformist painting that was little liked in Florence (and Rosso was not, in his own right, a character who enjoyed particular sympathy). Pontormo: impatience that becomes alienation, a painter who embodied the cliché of the moody and out-of-touch artist, but who perhaps simply did not feel at ease in a society that was experiencing very strong and sudden changes, and who delegated to the brush the task of tracing his own anguish with a painting that denies the laws of physics with bold and impossible poses, with ethereal characters that seem to lose their corporeity, with delicate and unnatural colors. And this while inserting himself into the theological debates of the time: echoing the Pietà of Luco, Pontormo’s Deposition (a deposition without cross or tomb) intends to affirm the validity of transubstantiation through the angels laying Christ’s body not from the cross nor in the tomb, but directly in the arms of the priest officiating at Mass in front of the canvas, as if to say that in the host distributed to the faithful there really was the body of Christ. Bronzino: an artist who, with those icy colorings and cold expressions peculiar to him, similarly delivers his own considerations around the theme of the Eucharist to the angel on the left who displays the chalice.

Works, those of Michelangelo, Andrea del Sarto, Pontormo, Rosso and Bronzino, brought to Florence just to make money and attract an audience, as some insinuate, reinvigorating the fire of controversies so obvious that they were even anticipated in the catalog? As much as the first two rooms may be endowed with the theatricality of a blockbuster exhibition, it is undeniable that the itinerary set up in these rooms (as well as in the continuation) is coherent with the objectives of the exhibition and the themes dealt with (both in the rooms of Palazzo Strozzi and in the catalog): it is impossible to think of an exhibition on the second half of the 16th century in Florence without Michelangelo, unlikely to introduce the theme of the theological debates of the time without the Pietà of Luco, difficult to imagine the works of the artists of the second half of the century without the models they looked to. It is a matter of balance: it is certainly a unique occasion to see the three Depositions together, and at the same time we can imagine that the exhibition would certainly have been a considerable success even without bringing Rosso’s altarpiece from Volterra (whose presence can be considered indispensable for popular and didactic purposes, while for purely iconological purposes it would have figured better, e.g, the Dead Christ once in the Cesi Chapel in Santa Maria della Pace in Rome and now in Boston), just as we can remark that the exhibition has triggered a mighty restoration campaign that has involved, among other emergencies, the Capponi Chapel itself, which will reopen once the exhibition is over (an eventuality that leads us to overlook the discussions about moving Pontormo’s Deposition ). Finally, it is necessary to reiterate how the title of the exhibition, which might suggest a much more extensive review than it actually appears, does not correspond to what was initially imagined by the curators who, with greater coherence and as anticipated in the opening, would have wanted to insist on the theme of the “sacred and profane” in the art of the second half of the 16th century. But we do not discover today that, especially in exhibitions of this magnitude, the reasons of curatorship must sometimes come to terms with those of commerce: not to mention that the displacement of works (consider, moreover, that the five masterpieces are not the only works being moved: many of the paintings on display come from Florentine churches), where there are obvious and strong scientific motivations, is still a more than acceptable practice.

|

| Michelangelo’s River God and Andrea del Sarto’s Pieta di Luco at the Florentine 16th-century exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi in Florence |

|

| Andrea del Sarto, Lamentation over the Dead Christ (Pieta di Luco) (1523-1524; oil on panel, 238.5 �? 198.5 cm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries, Palatine Gallery) |

|

| Andrea del Sarto, Lamentation over the Dead Christ (Pietà di Luco), detail |

|

| Michelangelo Buonarroti, River God (c. 1526-1527; Model in clay, earth, sand, plant and animal fibers, casein, on wire core; later interventions: plaster, iron mesh; 65 �? 140 �? 70 cm; Florence, Accademia delle Arti del Disegno) |

|

| The three depositions at the Palazzo Strozzi exhibition in Florence |

|

| Pontormo, Deposition (1525-1528; tempera on panel, 313 �? 192 cm; Florence, Church of Santa Felicita) |

|

| Rosso Fiorentino, Deposition from the Cross (1521; oil on panel, 343 �? 201 cm; Volterra, Pinacoteca and Museo Civico) |

|

| Bronzino, Christ Deposed (c. 1543-1545; oil on panel, 268 �? 173 cm; Besançon, Musée des Beaux-Arts et dArchéologie) |

Indeed, it is necessary to emphasize that the theological premises of the paintings in the first few rooms open the field to what the visitor encounters as he or she progresses through the itinerary: this particular value of the first two halls is also underscored by the presence of a painting of capital importance such as theImmaculate Conception by Giorgio Vasari (Arezzo, 1511 - Florence, 1574), a work in which the theme of the Virgin’s unblemished conception is treated with a strong emotional tension (observe the bodies of the two progenitors, moreover indebted to a drawing by Rosso Fiorentino kept at the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe in the Uffizi), such that it ensured Vasari’s work considerable success, and he found himself replicating it (the version now in the Museo Nazionale di Villa Guinigi in Lucca is probably even more dramatic than the first, which the artist from Arezzo executed between 1540 and 1541 for the wealthy banker Bindo Altoviti). With these premises having been achieved, the next room cannot but be dedicated to the altarpieces of the Counter-Reformation: the Council of Trent ended in 1563, and the ideologies that resulted inevitably ended up dictating guidelines in art as well. The paintings in the third room of the exhibition, almost all of which were executed within a fifteen-year period, make the visitor aware of what happened in those crucial years for the history of art, and not only for Florentine art.

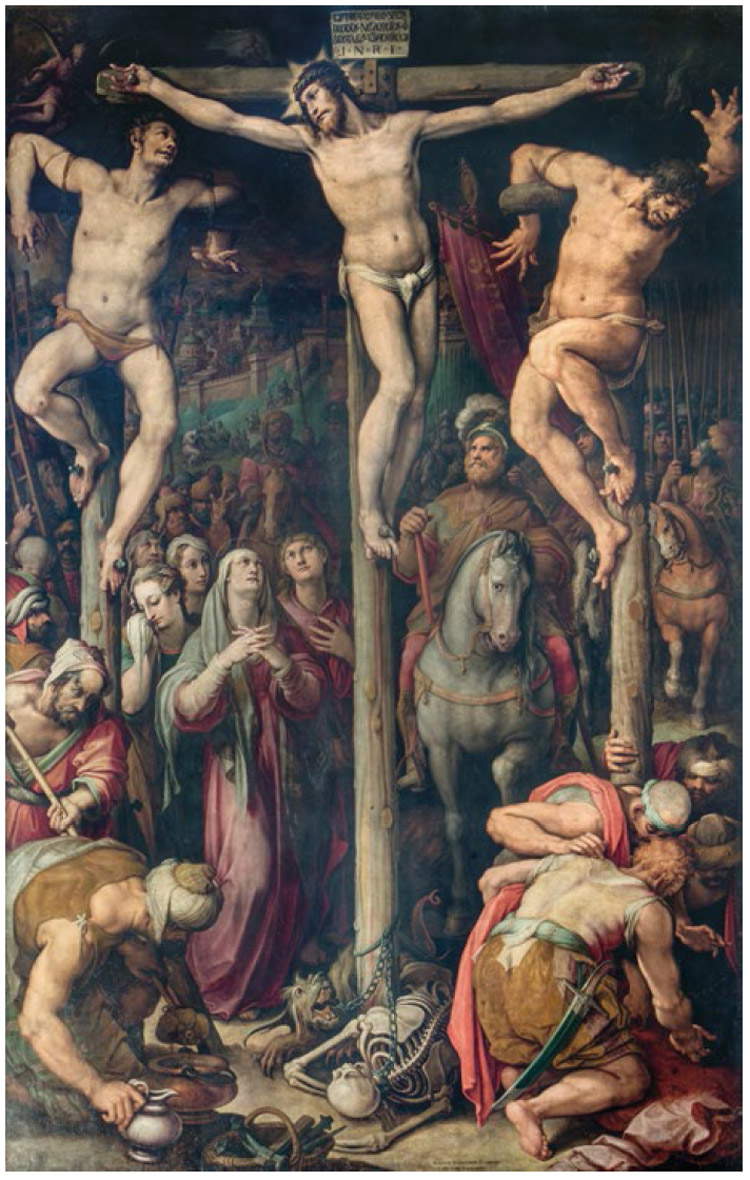

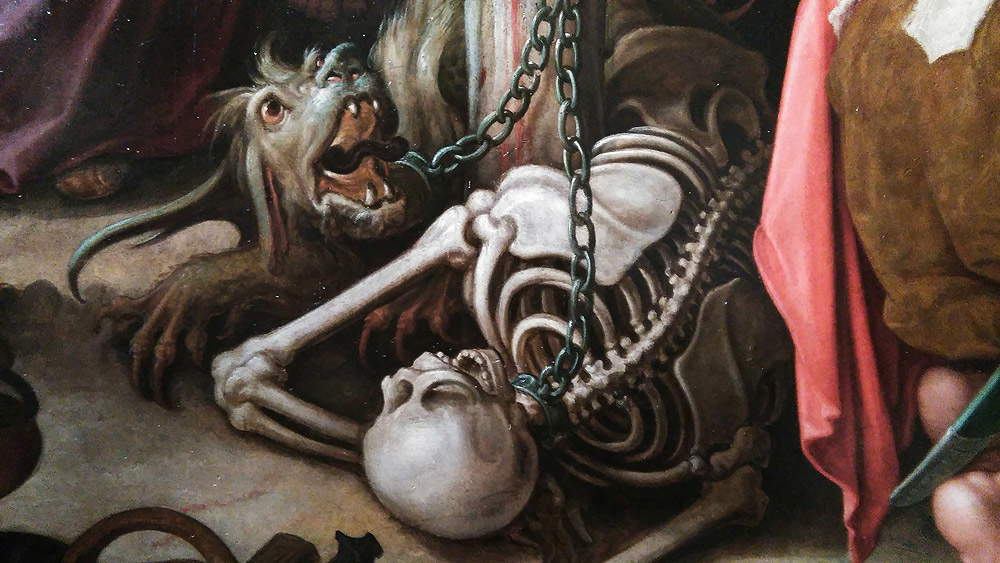

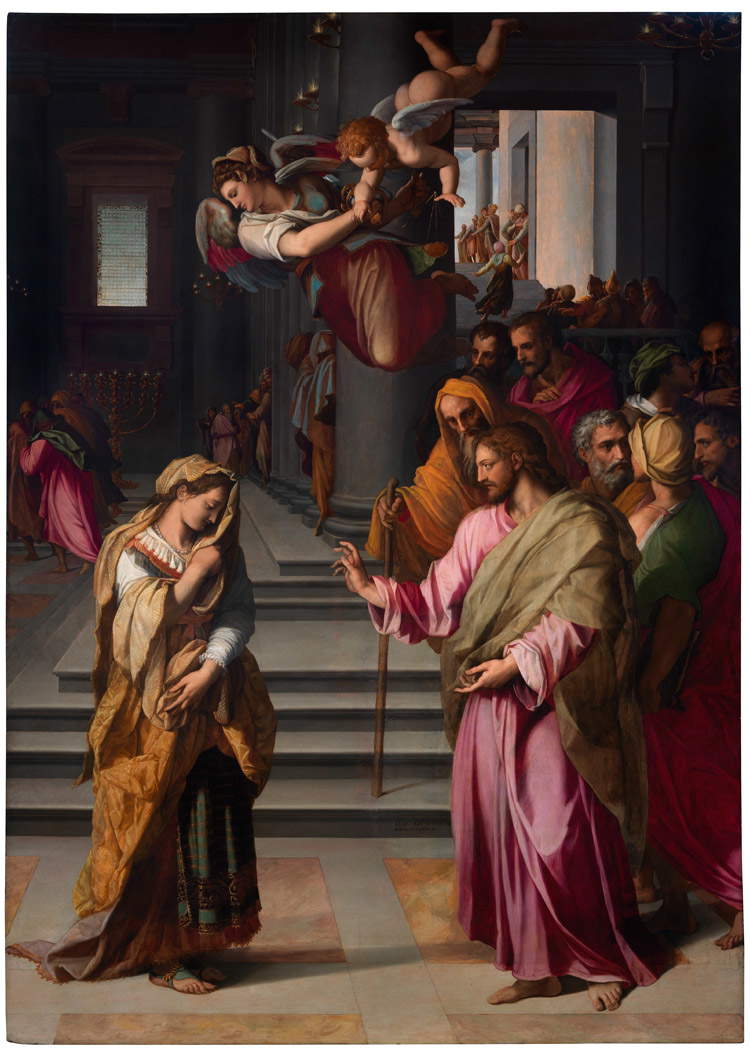

Take, as a point of reference, the Resurrection by Santi di Tito (Florence, 1536 - 1603), one of the most eminent protagonists of that season. A work executed for the Medici altar of the Basilica of Santa Croce (and still in situ, like many of the paintings that were brought to the exhibition), the Resurrection presents at its center a Christ victorious over death who towers with his powerful and well-turned physique, almost a classical divinity (the important thing, in representing the nude figure of Jesus, was to paint him “with that greater honesty that fusse been possible,” as one of the protagonists of Giovanni Andrea Gilio’s Dialogo degli errori e degli abusi dei pittori, published in 1564, asserted: the debate on the nude in sacred images was one of the most heartfelt of the time), and alongside him a host of angels depicted according to the prescriptions of the time, as Antonio Natali recalls in the aforementioned essay, citing again Borghini’s Riposo: “gli Agnoli deono esser dipinti bellissimi giovani, modesti, e con lAli, [....], so as to make them different from other young men, and so as to show in them the readiness and speed in following the precepts of God, and so because in this way it has always been used to paint them [...]. They must then be painted beautiful young men, because such are read in scripture to have always appeared, and because they are different from the evil Demons, who are to be painted ugly, and frightening.” In the same room we also punctually find an “ugly and frightening demon,” the one Giovanni Stradano (Jan van der Straet, Bruges, 1523 - Florence, 1605) paints at the foot of Jesus’ cross in his Crucifixion, along with an equally disturbing skeleton, signifying that Christ, by his sacrifice and subsequent resurrection, was able to triumph over evil (the horrifying monster writhing under the wood) and death (the grim skeleton). These are paintings that are easy to read, as the dictates of the time dictated, but which at times did not forgo precious details or refined compositions, as Alessandro Allori ’s Christ and the Adulteress (Florence, 1535 - 1607), from the Basilica of Santo Spirito, a work whose narrative takes place inside a Florentine church with Renaissance architecture, demonstrates with palpable evidence: the figures, while not failing to contextualize the episode, are arranged in such a way that the viewer’s attention is focused on the protagonist (and perhaps also on her fine, finely decorated robes) and on the figure of Christ who redeems her.

|

| Giorgio Vasari, Immaculate Conception (1540-1541; oil on panel, 350 �? 231 cm; Florence, Church of the Holy Apostles and Blaise) |

|

| Santi di Tito, Resurrection (c. 1574 mixed media on panel; 456 �? 292 cm; Florence, Basilica of Santa Croce) |

|

| Giovanni Stradano, Crucifixion (1569; oil on panel, 467 �? 293 cm; Florence, Basilica of the Santissima Annunziata) |

|

| Giovanni Stradano, Crucifixion, detail |

|

| Alessandro Allori, Christ and Ladultera (1577; oil on panel, 380 �? 263.5 cm; Florence, Basilica di Santo Spirito) |

|

| Alessandro Allori, Christ and the Ladultera, detail |

The theme on which we have chosen to set the reading offered in the present article remains suspended for a couple of rooms: the exhibition wanders in order to immerse itself in the context of the society of the time, first with a room devoted to portraits, then with a room entirely focused on that synthesis of styles that was the Studiolo of Francesco I. Portraiture was a true mirror of society, as Philippe Costamagna writes in his catalog essay, where we read that portraiture, for the Medici, represented a way of asserting their power and prestige (a sort of propaganda method, we would say), while, for the Florentine patrician families, the quickest way to “dissimulate”, in the eyes of the European courts, the fact that they had made their fortunes through trade and banking: space, therefore, for images that served as status symbols and were able to impress guests or, in general, those who found themselves observing them. To the latter case belongs one of the most singular works on display at Palazzo Strozzi, the Portrait of Sinibaldo Gaddi by Maso da San Friano (Tommaso Manzuoli, Florence, 1531 - 1571), where the infant, the latest arrival in the home of one of the richest families in Florence at the time, is carried by a black page, wears coral bracelets, sits on a wooden cabinet on which a silver vase rests, and extends a cookie to a spaniel portrayed with extreme skill. What seems to us a tasteful scene of everyday family life is in fact a clear display of luxury: as if to say that the Gaddi family was so wealthy as to afford a Moorish page, fine furniture and furnishings, expensive jewelry, and even pastimes (hunting) usually reserved for families of higher lineage. There is a lack of portraits by Bronzino, the Medici court portraitist, but we can be content with his epigone Alessandro Allori, who is present with a Portrait of a Lady with a distinctly Bronzinesque flavor, and also some curiosities, such as the portraits of the Sirigatti couple, which owe their uniqueness to the fact that they were executed by the couple’s son, Rodolfo Sirigatti (Florence, 1553 - 1608), who was not a professional artist, but rather a Medici official and merchant who occasionally dabbled in sculpture (on closer inspection with more than flattering results).

As for the “styles of the Studiolo,” it should be noted that the Palazzo Strozzi exhibition brings together for the first time the six lunettes (all unpublished except for Pietro Candido’sHumility ) executed by a number of artists involved in the undertaking of Francesco I’s Studiolo in the Palazzo Vecchio (which brought together many of the greatest artists of the time) and which constitute a singular cycle of a secular nature. We do not know the commissioner, but we can go so far as to say that these images, “almost as if they were words to be joined in a rhetorical discourse [...] still speak to us of the commissioner’s austere vision of life,” "and of how he had to firmly believe that only Fatigue and Humility were capable of leading him to Honor and guiding him in a behavior inspired by Justice: a set of virtues capable of defeating the Time that devours everything, and of leading him finally to Truth, which also in the Discourse above Baldini’s Masquerade was called the daughter of Time" (so Carlo Falciani in the catalog entry). Those just listed are, precisely, the subjects of the six lunettes: Fatigue (Santi di Tito), Humility (Pietro Candido), Justice (Francesco Morandini known as Poppi), Honor (attributed to Giovanni Balducci known as Cosci), Time (Giovanni Maria Butteri), and Truth (Lorenzo Vaiani dello Sciorina). Protagonists of a cycle that sought to affirm the values in which its patron believed and that reflect the spirit of the time.

|

| Maso da San Friano, Portrait of Sinibaldo Gaddi (post 1564; oil on panel, 116 �? 92 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Rodolfo Sirigatti, Portraits of Cassandra and Niccolò Sirigatti (Cassandra: 1578; marble, 85 �? 65.7 �? 35.5 cm; London, Victoria and Albert Museum; Rodolfo: 1576; marble, 73.5 �? 69.5 �? 48 cm; London, Victoria and Albert Museum) |

|

| Santi di Tito, La Fatica (1582-1585; oil on panel, 79 �? 100 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| Pietro Candido, LUmiltà (1582-1585; oil on panel, 83 �? 118 cm; Walnutport, St. Pauls United Church of Christ of Indianland) |

|

| Francesco Morandini known as Poppi, La Giustizia / Constans Iustitia (1582-1585; oil on panel, 80 �? 99 cm; Private Collection) |

So we return to the theme of the contrast between sacred and profane in the last rooms, the first of which is totally dedicated to myths and allegories, and introducing us to the context is precisely that Fata Morgana by Giambologna (Doaui, c. 1529 - Florence, 1608) whose nudity opens up for us a world of uncoverederoticism and uninhibited sensuality, practiced even by those artists who, in works of public commission, were careful not to step out of the seed of counter-reformed instances. A kind of double morality, however, that has left us masterpieces of undisputed value, and which also in this case had different ends: the myth could be political allegory, as was the case in works commissioned by the Medici; it could allude to contingent situations or vicissitudes that the artist or his patron were (or had been) forced to face; or, simply, it was a simple narrative intended for the private enjoyment of those who ordered the work that depicted him. Probably belonging to the former case is Maso da San Friano’s well-known Fortress: a vigorous female nude, with indeed rather masculine features, with her breasts encircled by a gold breastplate that leaves them uncovered, rests her foot on the head of a lion, stands out against a landscape where we notice Hercules struggling with his labors (on the right, we see him wrestling with the Nemean lion) and probably embodies one of the virtues befitting Medici rule (the work is in fact probably commissioned by the Medici, although no document can attest to this with certainty).

Instead, it is a figuration that takes on the tribulations of its author the celebrated Porta virtutis by Federico Zuccari (Sant’Angelo in Vado, 1539 - Ancona, 1609), a work in which the painter staged a complex allegory to take revenge on Paolo Ghiselli, Gregory XIII’s scalco, who had initially commissioned an altarpiece from Zuccari, which was later refused and returned to sender. On October 18, 1581, the day of St. Luke, the patron saint of painters, Zuccari exhibited the cartoon of the Porta Virtutis (the canvas that remains to us today is a replica) by hanging it on the façade of the church of San Luca in Rome: it did not take long to realize that the artist, painting the donkey-eared ignoramus sobered by flattery and persuasion, did not really aim to propose casual references, so much so that he was banned from Rome. Finally, an example of a painting probably intended for the secret rooms of its patron (whom we currently ignore) is Jacopo Zucchi ’sAmore e Psiche (Florence, 1541 - Rome, 1596), a work of an erotic nature, illustrating the moment in the fable when the beautiful girl discovers the identity of her lover, the god Amore (whose pose is reminiscent of Michelangelo’s river god). And although a couple of details, namely the belt and the bouquet of flowers, are meant to conceal the genitals of the two protagonists, the result is that such details prompt us to linger even more on the graces of the two young lovers (in love, the poetry of a refined concealment to be elegantly revealed must have had a fair amount of appeal even at the time). Impossible then not to highlight the further coup de théâtre of Giambologna’s sensual Venus Anadiomene, placed in the center of the room to make even more manifest the meanings of the paintings that dot the room.

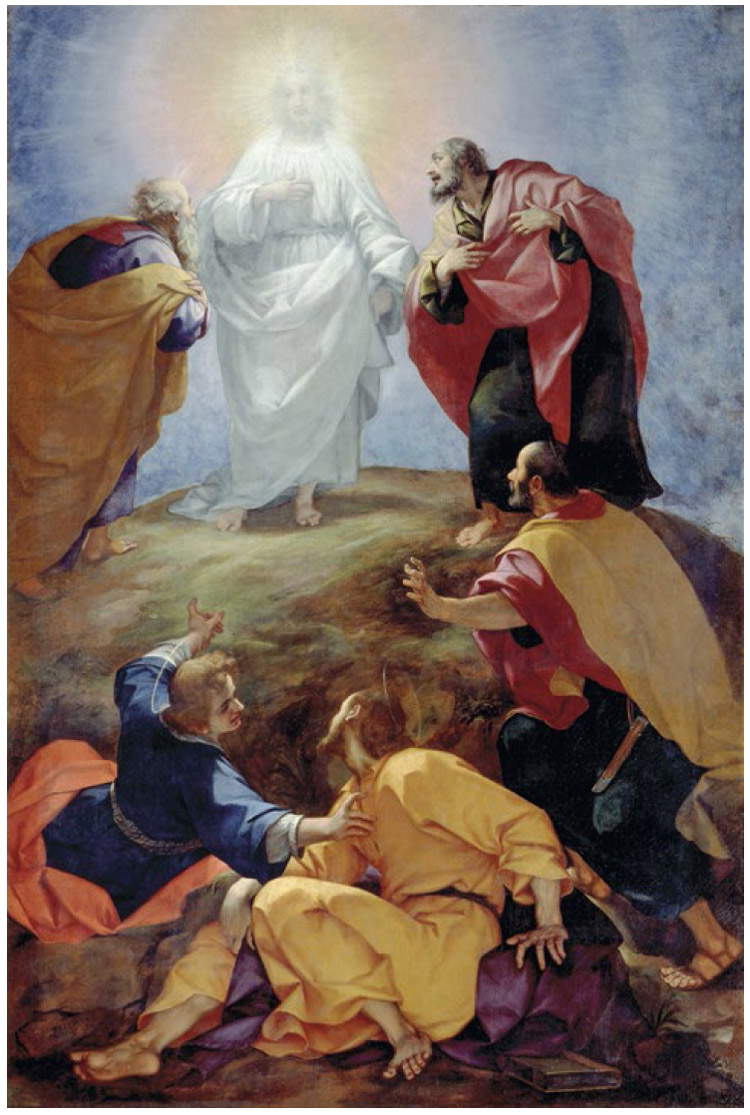

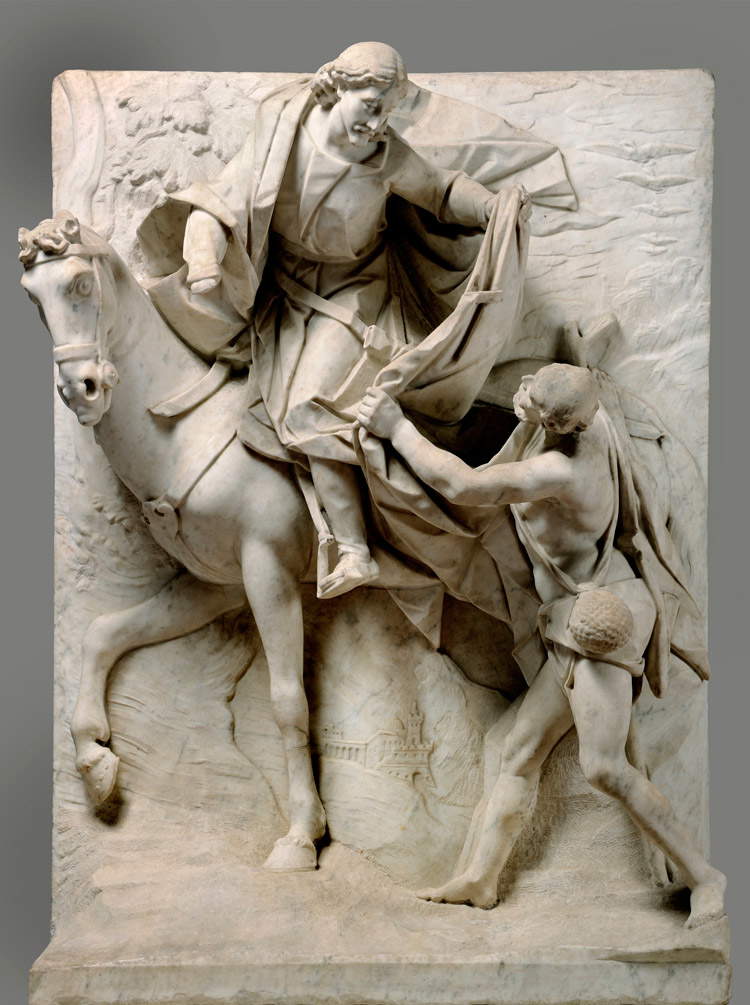

The exhibition concludes with a gateway to the seventeenth century: at the end of the sixteenth century, Florence is still a city dominated by the art of the Counter-Reformation, but the modes of expression open up, writes Carlo Falciani, “to new forms of representation, metaphorical or narrative, of a nature profoundly changed in the conception of its foundations.” The Transfiguration by Giovanni Battista Paggi (Genoa, 1554 - 1627), a Genoese in exile in Florence, is a particularly indicative painting: the convulsive gestures of the apostles witnessing the supernatural event (look at St. John, who almost goes so far as to shake St. James to show him, with the forefinger of his left hand, what is happening before them) foreshadow future trends, notably the strong emotional involvement of the faithful that will be characteristic of seventeenth-century art. And equally endowed with expressive power is a sculpture, St. Martin Dividing the Cloak with the Poor Man, by Pietro Bernini (Sesto Fiorentino, 1562 - Rome, 1629), father of the great Gian Lorenzo, which offers the viewer a decidedly foreshortened point of view to decisively engage the faithful who observe it from below: this is the work that, opening to the new century, worthily concludes the exhibition itinerary.

|

| Maso da San Friano, The Fortress (1560-1562; oil on panel, 178 �? 142.5 cm; Florence, Galleria dellAccademia) |

|

| Federico Zuccari, Porta Virtutis (post 1581; oil on canvas, 159 �? 112 cm; Urbino, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche) |

|

| Jacopo Zucchi, Cupid and Psyche (1589; oil on canvas, 173 �? 130 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

|

| Jacopo Zucchi, Cupid and Psyche, detail |

|

| Giambologna’s Venus before the Virtue by Jacopo Ligozzi |

|

| Giovan Battista Paggi, Transfiguration (1596; oil on canvas, 380 �? 260 cm; Florence, San Marco) |

|

| Pietro Bernini, St. Martin Divides His Cloak with the Poor Man (c. 1598; marble, 140 �? 102 �? 48 cm; Naples, Certosa and Museo di San Martino) |

The Sixteenth Century in Florence. Modern Mannerism and the Counter-Reformation thus stands as an excellent epilogue to Antonio Natali and Carlo Falciani’s trilogy of the manner, which began in 2010 with the monographic exhibition on Bronzino and continued in 2014 with the exhibition on Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino. An exhibition for which three years of work were necessary (as indeed befits a thoughtful and rigorous exhibition). Of course it remains undeniable that, as mentioned in the opening, the title is devoted to an excess of comprehensiveness, and many themes, albeit important, in the exhibition are barely touched upon (this is the case, by way of example, of the comparison of the arts, one of the main debates that animated the cultural life of Florence at the time): but of this the curators are fully aware, as they have let slip from the statements (and even from the essays in the catalog), and we like to continue to imagine this exhibition with the wonderful title “Lascivia e divozione” that was intended from the beginning.

All in all, a very interesting exhibition that continues previous experiences on the Florentine sixteenth century (beginning with Il primato del disegno, the 1980 exhibition curated by Luciano Berti), proposing an original, often unpublished, and content-focused reading, which analyzes various aspects of an extremely varied panorama in which painters of very fine talent moved, even if little known to most (after all, the “big names,” fortunately absent from the titles, end with the first two rooms), and which entails a decisive re-evaluation of a period often wrongly considered to be one of decline. A review of content, and for this reason endowed with a clear and effective didactic apparatus: a serious exhibition cannot ignore the need to establish a direct relationship with its audience, and Natali and Falciani’s exhibition fully satisfies this objective as well. An exhibition, therefore, that finds several reasons for being, and that reminds us how scientifically grounded exhibitions (with all that this entails, also in terms of travel) constitute an indispensable tool for the progress of the subject.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.