by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 05/10/2018

Categories:

Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Masterpieces of the Fourteenth Century. Giotto's Workshop, Spoleto and the Apennines', in Spoleto, Trevi, Montefalco and Scheggino from June 24 to November 4, 2018.

It is difficult to fully understand Umbrian painting if one has never been to Umbria: there is no art historian who has not remarked how the art of the painters who were active in this portion of Italy is firmly based on close connections with its territory. Carlo Gamba, for example, recalled in the 1940s that Umbrian art proceeds from those suave outlines that Carducci sang in the Fonti del Clitunno, that the works of Umbrian artists, as was the case with the Sienese, merge with nature and that for this reason “they have no life unless seen in their environment,” and again that the painting of these places “has its own expression emanating from the physiognomy peculiar to the Umbrian landscape from the gentle mountain lines ’sloping in a circle’ around the middle course of the Tiber and the Trasimeno, sprinkled with green woods flourishing with crops, surrounded by a bluish atmosphere, emanating from the humid saps of the plain.” Gamba was introducing an important study on the painting of the Umbrian Raphael, but it is implied that the above reasoning applies to Umbrian painting of all times, particularly to that which the region was able to produce in the fourteenth century when, in the wake of the revolution that was taking place in Assisi, centers such as Perugia, Spoleto, Trevi, Montefalco and the surrounding area elaborated a pictorial style that almost seemed to describe the region itself: sometimes gentle as its countryside and elegant as the most beautiful streets of its cities, sometimes harsh and vigorous as its Apennines of woods and stones. Characteristics always in harmonious cohabitation.

But the development of Umbrian art (or rather: of Umbrian art to the left of the Tiber, to use the effective demarcation invented by Giovanni Previtali) began long before the greatest artists of the early fourteenth century found themselves converging on the city of St. Francis. Consider Spoleto, a place where, roughly between 1260 and 1320, took root “a host of painters and sculptors, perhaps even painter-sculptors,” who contributed “to forging a quite particular artistic landscape , connoted also by very specific types in the structure of the artifacts, in the orchestration of pictorial cycles, individual votive images, painted crosses and wooden crucifixes, mixed tabernacles of carving for the iconic center and painting for the narrative wings” (Andrea De Marchi). Spoleto was a center that was able to give a significant impetus to the rest of the region, and it was a city in which an autonomous school developed that, like those of Rimini or the Veneto, elaborated Giottesque cues in an original way, and indeed knew how to graft them onto an already strong base and an already established tradition. The events in and around Spoleto are now the protagonists of an exhibition, Masterpieces of the Fourteenth Century. The Worksite of Giotto, Spoleto and the Apennines, which in four Umbrian cities (Spoleto, Trevi, Montefalco and Scheggino) puts in place an attempt to stitch together a story that for several decades now has aroused the interest of many of the greatest art historians Italy has known. An exhibition that starts with a recent study (just three years old), which was carried out by Alessandro Delpriori, curator of the exhibition together with Vittoria Garibaldi and Bernardino Sperandio, and also known in the news as the courageous mayor of Matelica who did his utmost to save as many works as possible in the aftermath of the earthquake that struck central Italy in 2016. And his study, titled The School of Spoleto and published just a year before the disastrous event, was also extremely valuable because it made it possible to take a census of how much was in danger of being lost.

A work that, moreover, is in the wake of an illustrious tradition: when speaking of the Spoleto school and Umbrian art to the left of the Tiber, one is reminded of Roberto Longhi, who devoted one of his studies to 14th-century Umbrian painting (and who was perhaps the first to take a systematic interest in the subject, the subject of one of his famous university courses in 1953-54), or the aforementioned Giovanni Previtali, who devoted himself to the study of wooden sculpture, going so far as to hypothesize that painters were often also carvers, to continue with Carlo Volpe and Miklós Boskovits, who nurtured the idea of a further study on Umbrian fourteenth-century painting, which would never be followed by a concretization. And if The School of Spoleto sought to delineate the vicissitudes of the many individual Umbrian masters of the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries within a unitary and complex framework, the present exhibition constitutes the natural continuation “from life” of the suggestions that that study (new yes, but already cardinal) provided. A review where the public will not find big names. Indeed: it will not find names tout court, since the artists that the exhibition investigates, although they have clearly distinguishable personalities, different and each distinguished by its own traits of originality, are not identifiable on the basis of documents that have handed down to us their biographical data. They are therefore all anonymous and therefore identified, as is customary in such cases, from their most significant work, or from the place that preserves the highest number of works attributable to them.

|

| Hall of the exhibition Masterpieces of the Fourteenth Century, Trevi venue |

|

| Hall of the exhibition Masterpieces of the Fourteenth Century, Spoleto venue |

The itinerary of the works, arranged in the three venues of Spoleto, Trevi and Montefalco (in Scheggino, in fact, there is a documentation space on the itineraries that visitors can undertake among churches and convents in the area to extend what the exhibition proposes), can start from the section set up at the Albornoz Fortress in Spoleto, where the three personalities of the Master of the Palazze, the Master of Sant’Alò and the Master of the Farneto are investigated, three artists whose works, roughly between the 1390s and the 1410s, marked the transition from a painting that was still Cimabuesque to one that, on the contrary, was already looking to the young Giotto. One of the salient passages of the exhibition takes place precisely around the Master of the Palazze, a painter of transition, observing whose works one almost has the sensation, Delpriori suggests, of finding oneself before a representative of “a group of middle-aged artists, born within the thirteenth century and enthusiastic about Cimabue but not so young as to be able to grasp the novelties in the fashion of Giotto, who had experienced competition with the spatiality of the Nordic style.” in Spoleto is in fact exhibited, in its usual location (the National Museum of the Duchy of Spoleto housed in the Albornoz Fortress), what remains in Umbria of the frescoes that the painter executed for the Palazze monastery in Perugia (hence the name by which the artist has been identified), to which is added a reconstruction hypothesis formulated on the occasion of the review. An artist whom, as early as the 1970s, Bruno Toscano related to Cimabue, the Master of the Palazze is distinguished by his expressive painting, characterized by a marked narrative vivacity (this can be grasped well when observing the Derision of Christ), which reinterprets Cimabuesque art with savory originality, diluting its more magniloquent points.

And again Bruno Toscano was the first to study in great detail the surprising opisthographic (i.e., painted on both sides) astylar cross that serves as a stauroteca, that is, as a reliquary capable of containing fragments of the cross of Christ: at the base, the stauroteca, a masterpiece of the Master of Saint Alò, is enriched with two tablets bearing figures of saints preciously adorned and decorated with that linear finesse that connotes much thirteenth-century Spoleto painting. The vividness of these individually characterized figures (observe their intense gazes) hints at a certain closeness to the Master of the Palazze, but there are exquisitely assisiated characters that are instead absent in the work of the less up-to-date colleague (although it should nevertheless be considered that the stauroteca, which moreover still preserves some relics, can be dated to the first decade of the 14th cent, while the frescoes of the Palazze are placed in the latter part of the thirteenth century), such as certain similarities in some figures (Delpriori has identified some characters, in the array of saints, who appear not at all similar to the apostles encountered in the chapel of St. Nicholas in Assisi) as well as some stylistic traits (for example, the touches of white light under the draperies to highlight the protrusions). Also continuing on this Assisi wave is the large, almost two-meter crucifix where “the physical presence of the characters, the white border that moves all the garments and the naturalistic effort that makes Christ’s face as alive and real, with the foreshortening of the nostril, descend precisely from the frescoes of the Upper Basilica.”

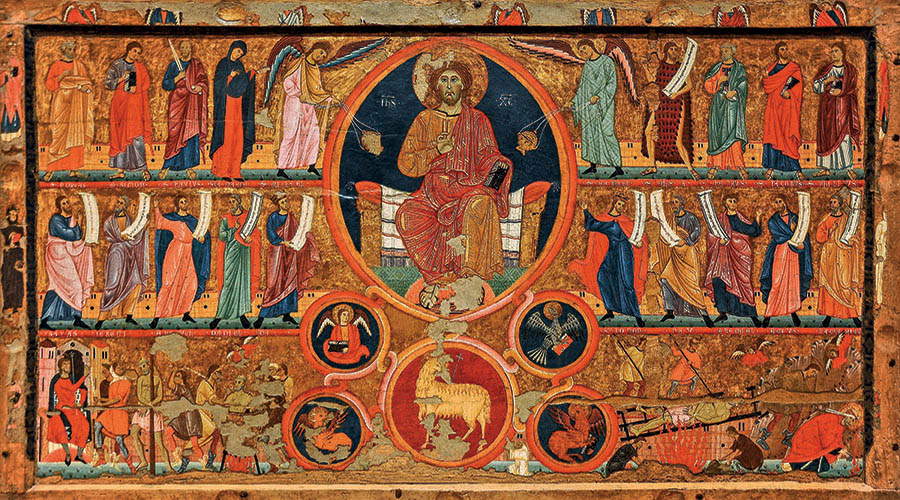

Among the early artists who followed Giotto is the Master of the Farneto, an artist whose personality was first traced by Roberto Longhi, and who is featured in the exhibition with the so-called Dossale del Farneto, on loan from the National Gallery of Umbria in Perugia. This is an artist who probably trained on earlier experiences (beginning with Cimabue himself) but who, in the group of the Madonna and Child who appears at the center of the composition, the fulcrum among the scenes of the Passion (note how Umbrian popular religiosity literally gouged out the eyes of Christ’s executioners as a sign of contempt: it is not uncommon in these parts to find works where the evil characters appear maimed in this way), separated from each other by interesting classical columns, was directly inspired by the Madonna and Child that Giotto frescoed in the chapel of St. Nicholas in the Lower Basilica: identical is the pose of the two characters, similar is the rendering of the affections, borrowed from the Tuscan painter is the gesture of the Child who slips his little hand into the Virgin’s neckline. Not only that: in his 2015 study, Delpriori had drawn interesting parallels between the Dossale del Farneto, the Majesty frescoed probably by the same master in the Basilica of San Gregorio Maggiore in Spoleto, and the Nativity of the Master of the Capture in Assisi, going so far as to raise the fascinating hypothesis that envisions “uniting the two artists in a single path of a personality who would begin his activity on the scaffolding in Assisi with the experience of Cimabue and then continue until he became the person responsible for the dossal now in Perugia.” A new hypothesis, revived on the occasion of the current exhibition and therefore all to be investigated.

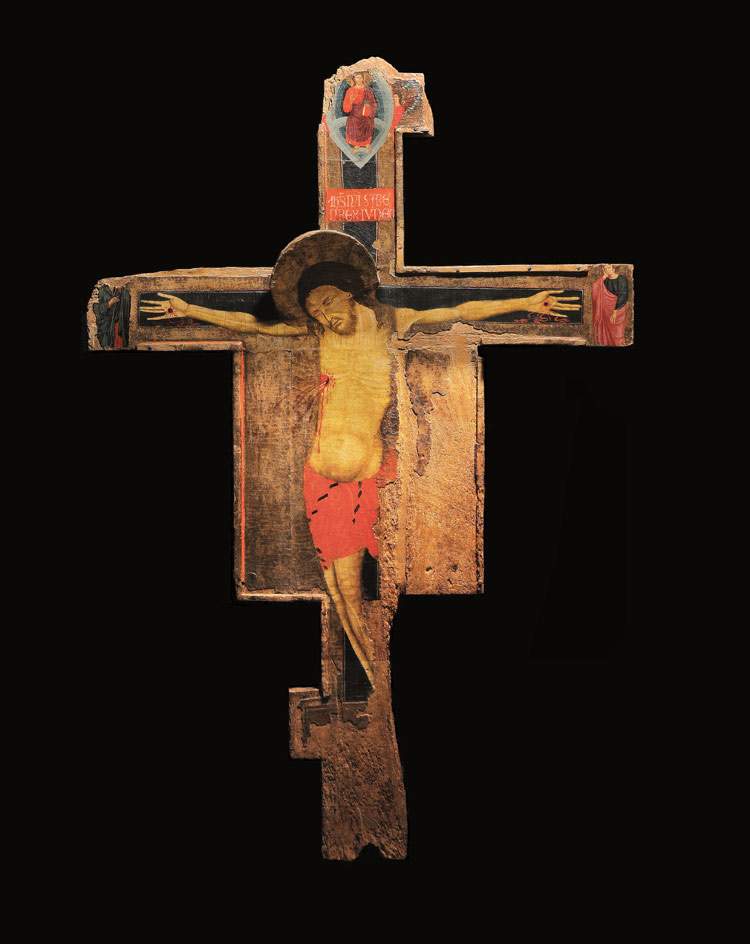

Still in Spoleto, but moving to the basilica of Sant’Eufemia, another venue for the exhibition, it is possible to take a step back to appreciate the works of the Master of San Felice di Giano, active in the mid-13th century: the panel with Christ Blessing and Stories from the Passion of St. Felix of Massa Martana, an altar frontal where the figures are characterized by a pronounced linearism, is illustrative of his painting “made of vivid color contrasts, elegant elongated figures drawn by outlines , illuminated by minute highlights that define anatomy and drapery” (Vittoria Garibaldi) and which, it might be added, does not omit crude details, as is the case in the scene of the martyrdom of St. Felix of Massa Martana, which we observe below right. Also attributable to the Master of San Felice di Giano is the Giuntesque crucifix from the Stella monastery in Spoleto, a central work in the discussion of the extension of Giunta Pisano’s lesson in Umbria, and on display to be placed in a “textbook” relationship with the Christus triumphans by the Master of Cesi, an artist whose vivid naturalism derives from careful observation of the Assisian frescoes. Also on display by the Master of Cesi is the triptych with moveable wings now in Paris at the Musée Marmottan: also originally in the Stella monastery, it is reunited with the Christus triumphans for the first time since the 19th century.

|

| Master of the Palaces, Derision of Christ (c. 1290-1300; detached fresco, 307 x 200 cm; Spoleto, National Museum of the Duchy of Spoleto) |

| <img title=“The Fragments of the Frescoes of the Master of the Palazze” “ src=”https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2018/951/affreschi-maestro-delle-palazze.jpg“ alt=”The Fragments of the Frescoes of the Master of the Palazze“ /></td></tr><tr><td>The Fragments of the Frescoes of the Master of the Palazze</td></tr></table><br /><br /> <table class=”images-ilaria“> <tbody> <tr> <td><img title=”The room with the reconstruction of the frescoes of the Master of the Palazze“ ” src=“https://www.finestresullarte.info/review/images/2018/951/reconstruction-fresco-master-of-the-palaces.jpg” alt=“The room with the reconstruction of the frescoes of the Master of the Palaces” /> |

| The room with the reconstruction of the frescoes of the Master of the Palaces |

|

| Maestro di Sant’Alò, Opisthograph-stauric cross, verso (c. 1300-1310; tempera and gold on panel, 45 x 28.3 cm; Spoleto, National Museum of the Duchy of Spoleto) |

|

| Master of Sant’Alò, opisthograph-stauroteca astyle cross with the two tablets with saints |

|

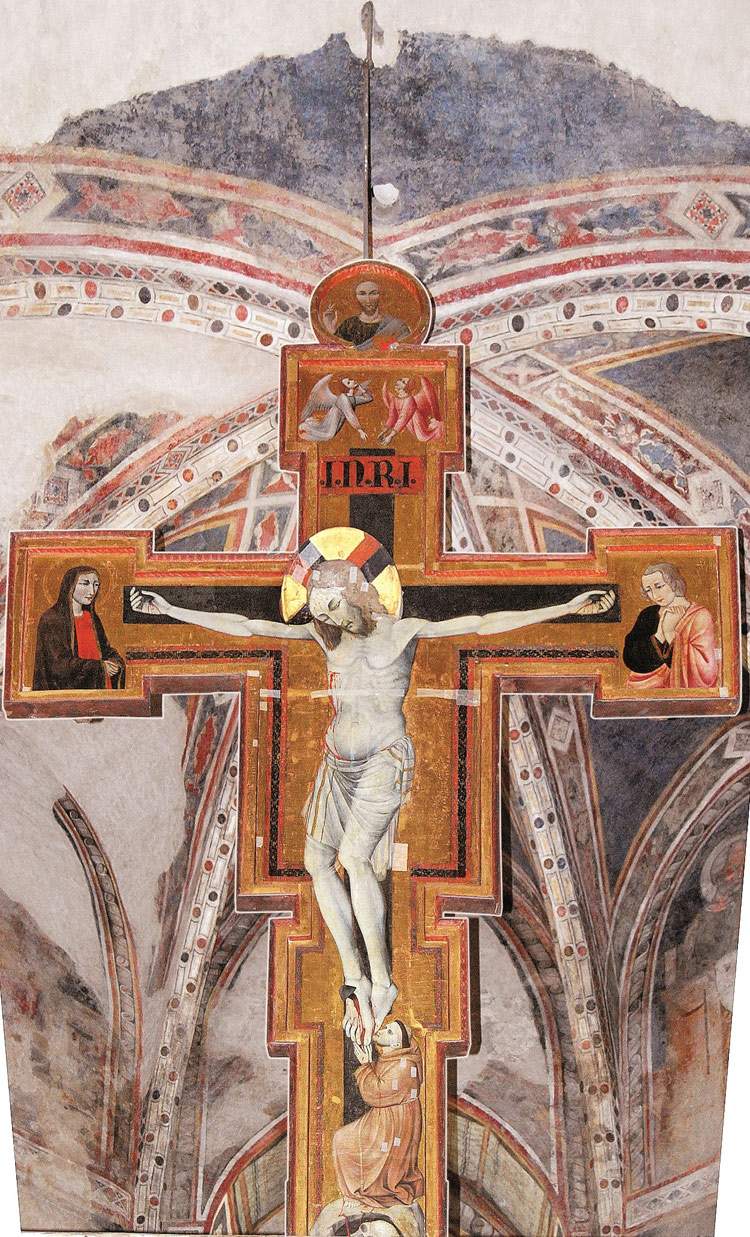

| Master of SantAlò, Crucifix (ca. 1290-1295; tempera on panel, 190 x 129 cm; Trevi, Raccolta dArte di San Francesco) |

|

| Master of the Farneto, Dossal of the Farneto (c. 1295-1300; tempera on panel, 58.5 x 207.5 cm; Perugia, National Gallery of Umbria) |

|

| Master of the Farneto, Dossal of the Farneto, detail |

|

| Master of San Felice di Giano, Christ Blessing and Stories of the Passion of Saint Felix of Massa Martana (c. 1250; tempera on panel, 104 x 176 cm; Perugia, National Gallery of Umbria) |

|

| Master of San Felice di Giano, Crucifix (c. 1270-1280; tempera and gold on panel, 140 x 98 cm; Spoleto, National Museum of the Duchy of Spoleto). Ph. Credit Matteo Passerini |

|

| Master of Cesi, Christus Triumphans (ca. 1295-1300; tempera and gold on panel, 245 x 158 cm; Spoleto, Rocca Albornoz - National Museum of the Duchy of Spoleto) |

|

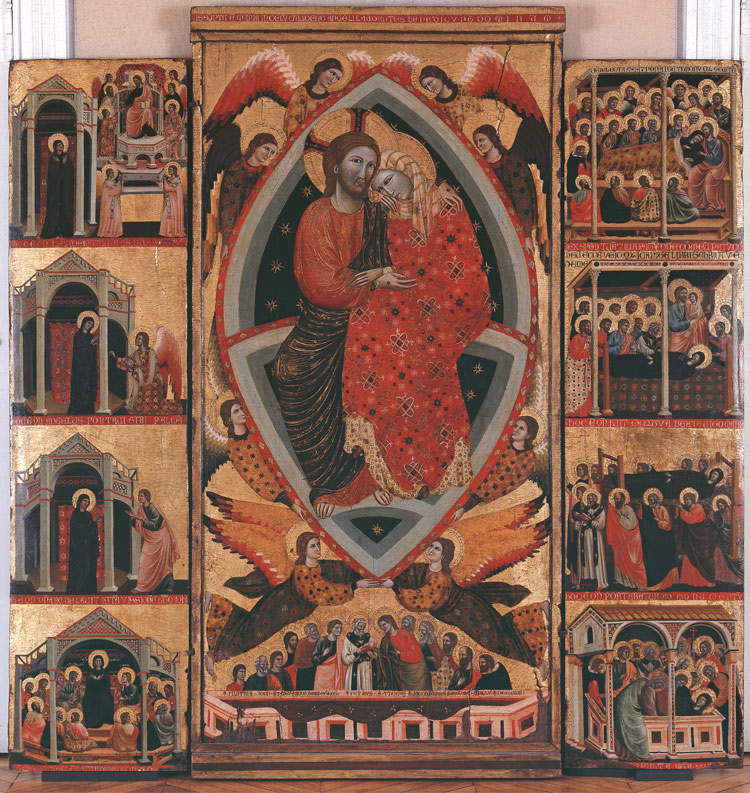

| Master of Cesi, Assumption of the Virgin and Stories of the Death of the Virgin (ca. 1295-1300; tempera and gold on panel, 186 x 91 cm the central panel, 177 x 46 cm and 177 x 44 cm the side panels; Paris, Marmottan Monet Museum) |

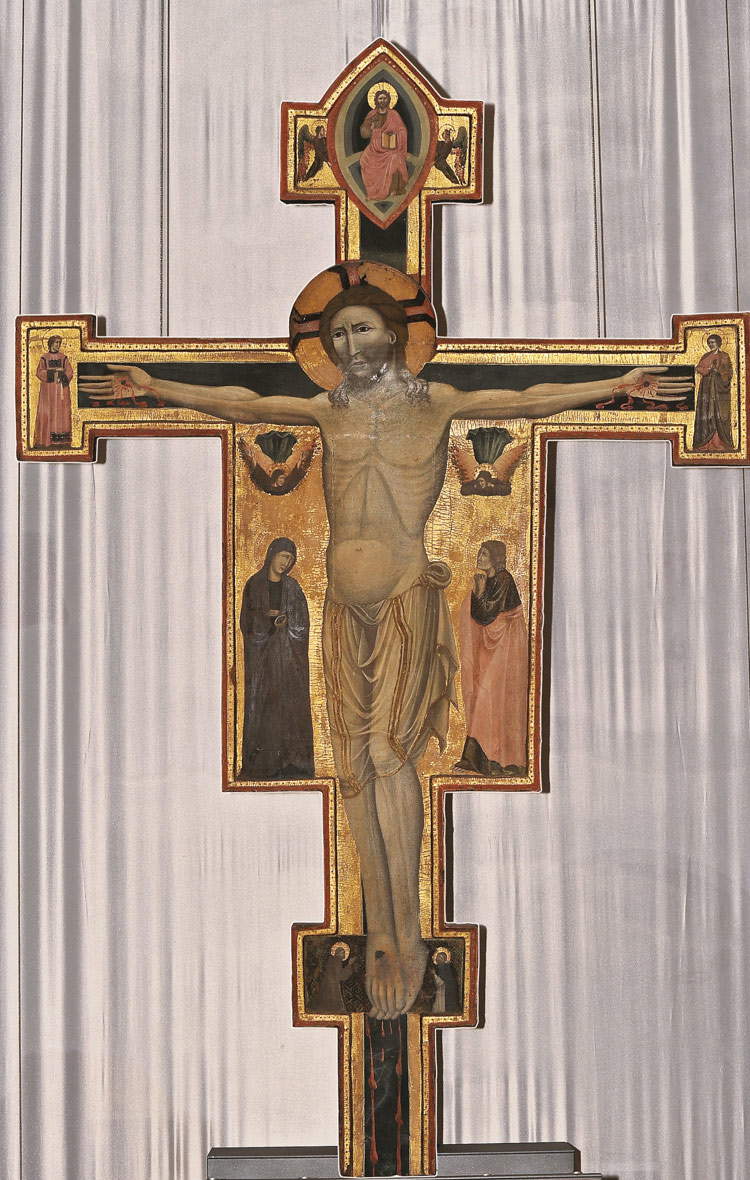

Among the keys to understanding the Trevi section, set up at the Museum of St. Francis, we can include that of the reflections that the Spoleto culture, updated on Assisi, managed to emanate during the 14th century: specifically, we get to follow them by closely investigating the relationship between a master and his pupil, respectively the Master of the Cross of Trevi and the Master of Fossa. In the punctual panels that accompany the public through the rooms of the exhibition, the Master of the Cross of Trevi is described as “the most beautiful” among the painters who worked in the Spoleto valley in the first decades of the 14th century. The reasons for such “beauty” are explained on the basis of the contacts that the master from Trevi had with the Sienese school, with the preciousness of Simone Martini and with the refinements of Pietro Lorenzetti, which enriched a style in turn indebted to Giotto’s ascendant. The section opens with a very elegant diptych on loan from the Galleria di Palazzo Cini in Venice, datable to a period roughly between 1325 and 1330: on the right wing the painter has depicted a composed Crucifixion, while the left is divided between a Derision of Christ at the top and a Flagellation in the lower register. A lyrical and “melancholic” work (in the words of Boskovits, who used this adjective to describe the small group in 1965), the Venetian diptych also looks to the Assisi frescoes, but dwells, as anticipated, on the Sienese painters: the elegant soldier on horseback recalls the Simone Martini of the San Martino chapel, while the militiaman on the right seems to be taken from the identical figure in the same position in Pietro Lorenzetti’sAndata al calvario, also in the Lower Basilica. From the Poldi Pezzoli Museum in Milan come instead two tablets, formerly part of a diptych, on which the Master of the Cross of Trevi depicted on the left anAnnunciation and a Madonna Enthroned with Saints, and on the right a Crucifixion, with the scenes surmounted by two small cusps bearing on the left the Stigmata of St. Francis and on the right the Flagellation. This is a work where the figures “exhibit a mature language, declining toward more Gothic and more developed rhythms” (Virginia Caramico in the catalog), still in the sign of Sienese painting: the more uncertain arrangement of the figures in space would suggest, however, that this is an earlier proof than the Venetian diptych.

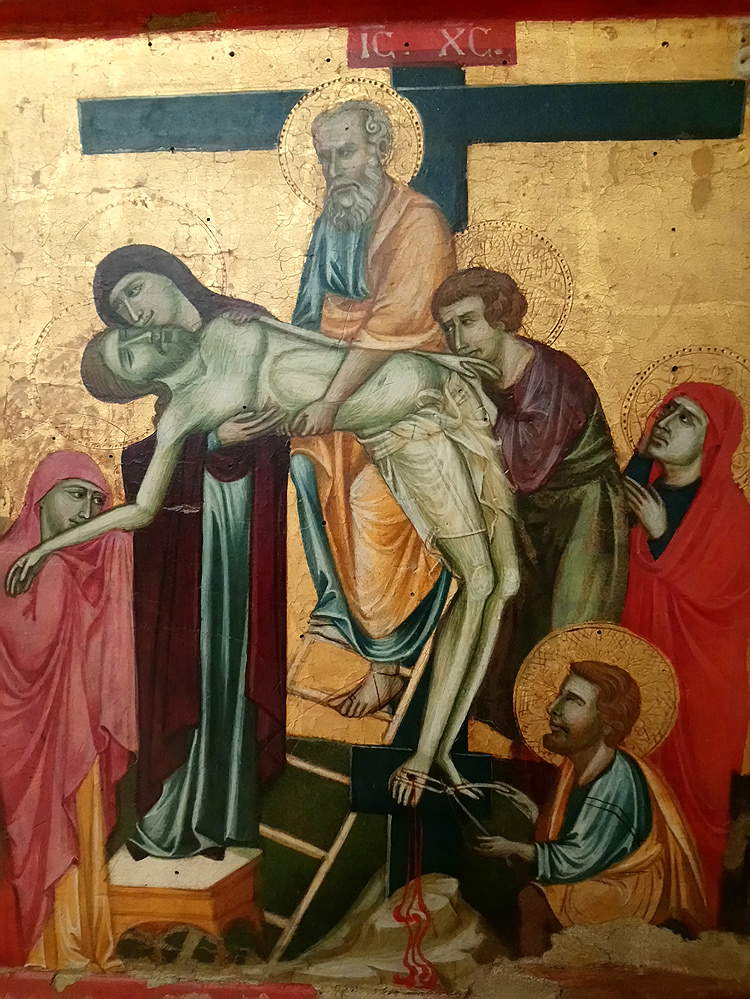

The large blue panels that mark the path of the Trevi section lead toward the works of the Maestro di Fossa. Occupying one entire wall is the large fresco with the Crucifixion flanked by theAnnunciation and the Madonna and Child Enthroned, from the convent of Santa Croce in Trevi and now housed in the Museo di San Francesco. A work that Longhi already studied in the aforementioned course of 1953-1954, it demonstrates all the characters of the artist, one of the most up-to-date of the Spoleto Fourteenth century: his refined and elongated characters hint at links with the Master of the Cross of Trevi (so much so that it has been hypothesized that he was an alumnus of the older Trevi painter’s workshop), but the latter’s mark is mitigated through a painting that becomes more delicate, sweet and graceful. To notice this, the viewer can dwell on the faces of the three Marys, traversed by a motion of composed sadness, and caught trying to comfort each other in a moment of extreme sorrow (the gesture of one of the Marys caressing the Virgin’s face is particularly touching). Equally elegant is also the Saint Peter the Martyr, who presents a wispy and delicate complexion, further evidence of the softness of the painting of the Master of Fossa. An artist who, as was often the case in 14th-century Umbria, was also a sculptor as well as a painter: his is a wooden group of the Nativity arriving from Tolentino, which introduces what Delpriori calls “one of the great themes of all art in Spoleto and the Valnerina at the beginning of the 14th century,” that is, the relationship between painting and sculpture, one of the exhibition’s pillars (a pillar on which, however, we have decided to refrain from commenting for reasons of space). Concluding the Trevi section is the eponymous work of the Master of the Cross of Trevi, the large wooden crucifix of St. Francis, another clear evidence of how the Trevi painter had updated himself on the modern outcomes of Giotto’s painting.

Finally, the Montefalco section houses only five works, two of which, however, are important “returns.” they are, in fact, works on loan from the Vatican Museums, which return to their city of origin two centuries after the Napoleonic spoliations (the Polyptych of the Passion by the Master of Fossa, inventoried during the French occupation and then ended up nobody knows how in Rome) and about ninety years after being transferred to the Vatican (the seven-compartment dossal by the First Master of the Blessed Clare, sold in 1925 by the nuns of Santa Chiara to cope with economic difficulties). The work by the Maestro di Fossa, in particular, returns after two hundred years to the place for which it was conceived, the church of San Francesco in Montefalco: it was restored on the very occasion of the exhibition, and the intervention made it possible to reassemble the five panels of the polyptych according to the original order and to resurface an inscription that attests to the date of its creation (1336) and the name of the commissioner (Jean d’Amiel, an important member of the French clergy, formerly rector of the Duchy of Spoleto and later to become bishop of Spoleto, in 1348). It is a work of capital importance: Adele Breda notes that “the refinement of style and the miniaturistic accuracy of the painting’s pictorial execution allow the polyptych to be recognized as a production of the very special Frenchizing artistic milieu of the Duchy of Spoleto, in a period when continuous cultural exchanges between France and central Italy are documented.”

|

| Master of the Cross of Trevi, Diptych with Derision, Flagellation and Crucifixion of Christ (c. 1325-1330; tempera and gold on panel, 45.5 x 58 cm; Venice, Giorgio Cini Foundation, Galleria di Palazzo Cini) |

|

|

Master of the Cross of Trevi, Annunciation and the Enthroned Madonna and Child, Saints Peter Martyr, Dominic, two martyred saints (tempera and gold on panel, 23.3 x 17.8cm), Crucifixion (tempera and gold on panel, 23 x 18 cm), Stigmata of St. Francis (tempera and gold on panel, 7.8 x 8.2 cm), Flagellation (tempera and gold on panel, 8 x 8.8 cm). c. 1320; Milan, Museo Poldi Pezzoli |

|

| Maestro di Fossa, Crucifixion, Annunciation and Madonna and Child Enthroned (c. 1330-1333; detached fresco, 350 x 475 cm; Trevi, Raccolta dArte di San Francesco) |

|

| Master of Fossa, Crucifixion, Annunciation and Madonna and Child Enthroned, detail of the three Marys |

|

| Master of Fossa, Saint Peter Martyr (c. 1335-1340; tempera and gold on panel, 189 x 99 cm; Spoleto, Church of San Domenico, Chapel of the Sacrament) |

|

| Master of Fossa, Nativity (c. 1340; carved and painted wood, the Madonna 61 x 135 x 27 cm, St. Joseph 115 x 50 x 40 cm, Baby Jesus 22.5 x 62 x 14 cm; Tolentino, Sanctuary Museum of St. Nicholas of Tolentino) |

|

| Master of Fossa, Nativity, detail of the Madonna and Child |

|

| Maestro della Croce di Trevi, Crucifix of St. Francis (c. 1320-1325; tempera and gold on panel, 353 x 229.5 cm; Trevi, Raccolta dArte di San Francesco) |

|

| Master of Fossa, Crucifixion and Stories of the Passion (1336; tempera, gold and silver on panel, 166 x 280 cm; Vatican City, Vatican Museums) |

It should be emphasized that the itinerary traced here is but one of many that visitors can take between the exhibition’s venues, and the themes alluded to are only some of those that emerge from the review. Masterpieces of the Fourteenth Century is an intelligent, research-based exhibition that stands in clear antithesis to that much in vogue today for exhibitions of ancient art, all aimed at focusing primarily on the names of individuals, often carefully selected in order to make the greatest possible impact on the public. In Masterpieces of the Fourteenth Century there is no yielding or compromise: it is, in essence, a pure exhibition that, reconstructing the plots of art in Spoleto and the Valnerina during the fourteenth century (an art, it will be appropriate to reiterate, little known), gathers the fruit of years of study and research, of which it represents the most tangible and concrete result in the eyes of the public.

It is then necessary to find that the exhibition derives value from being arranged over four venues, due to the fact that the widespread dislocation of the approximately seventy works of art selected by the three curators draws almost, in broad strokes, a map of the spread of the Spoleto school: a territory that does not correspond to any of today’s administrative subdivisions (so much so that the itineraries proposed in Scheggino also range beyond the regional borders), a territory often battered by natural events (much of the area in which the Spoleto school developed falls within the crater of the 2016 earthquake), and for which occasions such as the one represented by Capolavori del Trecento become a reason for challenge, to show the world that a wounded but strong territory is still able to react, to get back up with speed and readiness. A territory in which it is necessary to immerse oneself, as Alessandro Delpriori reminded several times, if one wants to “study art in Spoleto and in the Valnerina of the fourteenth century,” an activity that requires “patience and enthusiasm” in order to launch oneself into a reconnaissance capable of reserving in the end surprises as much for the scholar as for the enthusiast. And the exhibition will be all the more suggestive if one thinks that two locations, the churches dedicated to St. Francis in Trevi and Montefalco, were in ancient times centers from which radiated that new art that the review brings to the attention of the public: the works therefore return for a few months to their ancient location (in Umbria it is not uncommon to come across churches transformed into museums or exhibition venues), so that their scope, their charge, their “mystical and earthly spirit of true Franciscanism spread from the basilica of Assisi” (Vittoria Garibaldi) can be appreciated in those same places in which they should have spoken to the Umbrians seven centuries ago. The same Carlo Gamba who was quoted in the opening, moreover, was deeply convinced that “certain paintings” are “unbearable in series in a Gallery” and, on the contrary, “appear delightful and moving in a country church.” Perhaps this is the best formula to sum up a very high-profile exhibition that is inextricably linked to its territory, without which it would not even have a reason to exist.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.