by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 26/03/2018

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'The Last Caravaggio. Heirs and New Masters' in Milan, Gallerie d'Italia, Piazza Scala, from November 30, 2017 to April 8, 2018.

Do not make the mistake of being misled by the title: the exhibition The Last Caravaggio. Heirs and New Masters not only has little to do with the great Michelangelo Merisi (Milan, 1571 - Porto Ercole, 1610), but even questions, as a substantial premise, whether it is possible to delineate a history of seventeenth-century art that prescinds from Caravaggio. In other words: how far did Caravaggio’s influence on seventeenth-century art go? Can one find areas that remained impervious to the disruptive innovations introduced by the Lombard genius? To answer these questions, the exhibition curated by Alessandro Morandotti, and staged at the Gallerie d’Italia in Milan’s Piazza Scala, takes its starting point fromCaravaggio’s last painting, the Martyrdom of St. Ursula, executed in Naples for a commissioner from Genoa, and following the traces left by this extreme test of the Milan-born artist, sets off on an interesting journey that takes the visitor first to the shadow of Mount Vesuvius and then to the shores of the Ligurian Sea in order to retrace Caravaggio’s cues in Naples and Genoa and to analyze to what extent they fascinated local artists, and whether conversely there were others reluctant to welcome them. The history of Italian art is thus intertwined with the history of local art, and not only, since the exhibition (which, it should be emphasized, focuses for the most part on the Genoese situation than on the Neapolitan one, to which only one section is devoted: Genoa, on the other hand, is present throughout), focusing its attention also on the vicissitudes of the Doria collection, enters simultaneously into the history of taste and the history of collecting.

All the prerequisites are therefore in place for an exhibition with an original slant, one that looks at the history of seventeenth-century art with a magnifying glass, and which is certainly much more Genoese than Milanese, although the objectives also include the (excellently achieved) goal of analyzing the ties that Milan had with Genoa in the thirty years that the exhibition examines, i.e., that which goes from the year of Caravaggio’s disappearance, 1610, to 1640, the year in which, Morandotti writes in the catalog, the Ligurian capital experienced a “Caravaggesque blaze that invested the city starting from the rooms of Palazzo Spinola.” this is because it was precisely in 1640 that three masterpieces by Matthias Stomer (Amersfoort?, c. 1600 - Sicily?, after 1650), which according to the curator “shook the city of artists as Caravaggio’s painting had failed to do.” It is true that the echo of the Martyrdom of St. Ursula, a work destined for the Genoese collection of Marco Antonio Doria (Genoa, 1572 - 1651), passed almost unnoticed, but it is equally true that Genoa experienced a certain diffusion of Caravaggism, which was benefited by Caravaggio’s very presence in the city in the summer of 1605, as well as by the arrival of some important artists influenced by his lesson, including Orazio Gentileschi, Simon Vouet (about whom more will be said later) and Bartolomeo Cavarozzi (and regarding the latter, it is worth noting that precisely in parallel with the Gallerie d’Italia exhibition, an exhibition is being held in Genoa, made possible thanks to the support of Intesa Sanpaolo, which aims to shed light on Cavarozzi’s brief presence in Genoa and the interest that Ligurian collectors had in his work).

The Genoese school, however, elaborated Caravaggism in the light of local traditions as well as of other contributions (Genoa, at the beginning of the 17th century, knew the presence of a very large number of Flemish artists), with the result that Merisi’s lesson was only a component, often marginal, of a mosaic rich in many facets (the example of the “tempered naturalism”, as defined by Piero Donati, of a great artist such as Domenico Fiasella is worth mentioning): different, however, was the case in Naples, a city deeply Caravaggesque, which for some time recorded the physical presence of the Lombard painter, decisive for the maturation of a school that had in him the main point of reference and that developed around his legacy. Morandotti’s assumption, which wonders how it is possible that Genoa snubbed “the sublime evidence of a painter who at no time in the early history of his critical fortunes was so in vogue,” certainly provides much food for discussion, and it is to be expected that in the near future the witness of The Last Caravaggio will be somehow picked up, since much of the criticism that has dealt with the events of early seventeenth-century Genoa could not help but question how Caravaggio’s legacy was received in the city. Of particular importance in this regard is the contribution of Franco Renzo Pesenti, who as early as 1992 analyzed the “first moment of Caravaggism in Genoa,” without being able to avoid noting how Bernardo Strozzi himself (Genoa, 1581 Venice, 1644), who moreover perhaps made a trip to Rome, was affected by Caravaggio’s lesson. Instead, the Milan exhibition comes to different conclusions, and it is therefore worth delving into the themes it intends to address.

|

| Hall of the exhibition The Last Caravaggio. Heirs and new masters. Ph. Credit Maurizio Tosto |

|

| Hall of the exhibition The Last Caravaggio. Heirs and new masters. Ph. Credit Maurizio Tosto |

The opening is, of course, delegated to Caravaggio’s Martyrdom of Saint Ursula, placed in direct comparison with the counterpart works of Bernardo Strozzi and Giulio Cesare Procaccini (Bologna, 1574 Milan, 1625), Genoese the former, Emilian by birth but Milanese by adoption the latter. According to legend, St. Ursula, a Breton princess who lived in the fourth or fifth century, was killed with an arrow by Attila for refusing to give herself to him. In Caravaggio’s painting, the theme is approached with a drama that departs from the iconographic tradition that wanted St. Ursula depicted in the act of suffering martyrdom along with her fellow virgins: Conversely, the scene is charged with dramatic intimacy, with Attila, on the left, shooting the arrow at her, but seeming almost to regret the act, given his almost dismayed expression, contrasting instead with the firm expression of St. Ursula, who decides to be killed rather than renounce her illibacy and her faith, not without, however, opposing an attempt to remedy her fate (the gesture of her hands is particularly eloquent). The strong chiaroscuro contrasts heighten the tragedy of the saint, in which the character in the background, with his face struck by light and his mouth wide open, also seems to participate: a character in which some scholars have wanted to see a self-portrait of Caravaggio, who seems almost to suffer for the saint’s fate (as well as for himself: 1610 is the last year of his troubled life marked by excesses).

Of a different accent appear the paintings by Strozzi and Procaccini. Looking at the Genoese’s painting, one will realize that, if one is to accept the idea of an acceptance of Caravaggesque manners, they concern only the external aspects: the naturalism of the characters, their emergence from a dark background. Strozzi, however, shows that he does not grasp the essence of the Caravaggesque painting, that is, the rendering of the martyrdom of St. Ursula as an intimate drama, touching to the point of staggering the ruthlessness of her tormentors, who seem assailed by doubts and, as mentioned above, even appear to be participants in her pain. In Bernardo Strozzi this does not happen, and Saint Ursula, on the contrary, surrenders to her own end with an ecstatic expression, allowing herself to be struck by the arrow with her hands wide open (whereas Caravaggio’s Ursula closed them to herself as if to somehow arrest the wound inflicted by the dart). The same is true of Procaccini who, Morandotti points out, compared to Caravaggio, “goes his own way by firing a kind of old-fashioned relief, spectacular in its contrasting rhythms, perfectly balanced”: his figures are endowed with a sculptural monumentality (it should be remembered that Procaccini, at the beginning of his career, was also a sculptor) and the artist infuses the protagonists of the work with a spectacularity and energy that seem completely unknown to Caravaggio. The opening of the exhibition is thus clear: in Genoa and Milan, Caravaggio’s art would seem to have little fascination for the greatest artists active in the two cities.

|

| A comparison of the three versions of the Martyrdom of St. Ursula by Caravaggio, Bernardo Strozzi and Giulio Cesare Procaccini. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Caravaggio, Martyrdom of Saint Ursula (1610; oil on canvas, 143 x 180 cm; Naples, Intesa Sanpaolo Collection, Gallerie dItalia - Palazzo Zevallos Stigliano) |

|

| Bernardo Strozzi, Martyrdom of Saint Ursula (1615-1618; oil on canvas, 104 x 130 cm; Private collection. Courtesy Robilant+Voena) |

|

| Giulio Cesare Procaccini, Martyrdom of santOrsola (1620-1625; oil on canvas, 141 x 144.5 cm; Private collection) |

Different, however, is the case of Naples, after Rome the most distinctly Caravaggesque city. Michelangelo Merisi is present in Naples between 1606 and 1607 and then between 1609 and 1610. A solid link between Naples and Genoa is that established by Marco Antonio Doria himself, who had woven many affairs in Campania, but it is necessary to reiterate how a solid and numerous Genoese colony had long since been formed in Naples (and it is worth noting how Naples was already a very populated city at the time: 327.000 inhabitants surveyed in 1614, compared to 125,000 in Milan in 1610 and 67,000 in Genoa in 1608), which, Andrea Zanini explains in the catalog, “flanked traditional activities such as maritime trade and annonari supplies” with “an increasingly intense credit activity, both on the public and private sides.” Ligurian businessmen present in Naples felt the need to hold their economic power over the city, and thus to consolidate their presence in the Kingdom of Naples: hence the need to grab fiefs and noble titles, and not even the Dorias escaped this logic. Marco Antonio himself in 1612 had purchased the fiefdom of Angri, near Salerno, and in order to further entrench his presence in Naples he had taken to maintaining relations with local artists. The second section of the exhibition is an important junction, since on the one hand it makes us aware of the evolution of Caravaggism in Naples, and on the other it presents us with the interests of the Doria family.

Marco Antonio owned, in his own collection, nine paintings by Battistello Caracciolo (Naples, 1578 1635), one of the earliest Neapolitan Caravaggesque painters: of these nine paintings, only one has been traced, and it is featured in the exhibition. It is Christ Carrying the Cross, now housed in the Rector’s Office of the University of Turin. Caracciolo is perhaps the sternest exegete of Caravaggio’s lesson: his paintings (and Christ carrying the cross is an example, but one need only look at the Baptism of Christ on loan from the Girolamini picture gallery as well) show a meditation that develops above all the more distinctly dark component of Caravaggio’s art. These are paintings that retain the drama and restlessness of Caravaggio’s works, even acquiring mournful accents in some cases.This is not the case with José de Ribera (Xàtiva, 1591 Naples, 1652), a Spaniard by birth but active in Naples for almost his entire career, and another artist to whom Marco Antonio Doria accorded his preferences. Ribera (look in the exhibition at the intense St. Andrew, so naturalistic as to appear unpleasant, especially if one observes his gnarled, stubby, dirty hands) showed instead that he was more interested in the realism of Caravaggio, which enabled him to develop an art that was less dramatic and conversely much more attentive to the natural datum, the analysis of details, and the meticulous study of anatomy. In short, wrote Nicola Spinosa in 1988, an art based on an “ostentatious realism,” “more epidermal and less suffered, but certainly easier and more immediately communicative, even almost more straightforward than that provided by Caravaggio’s own prototypes.”

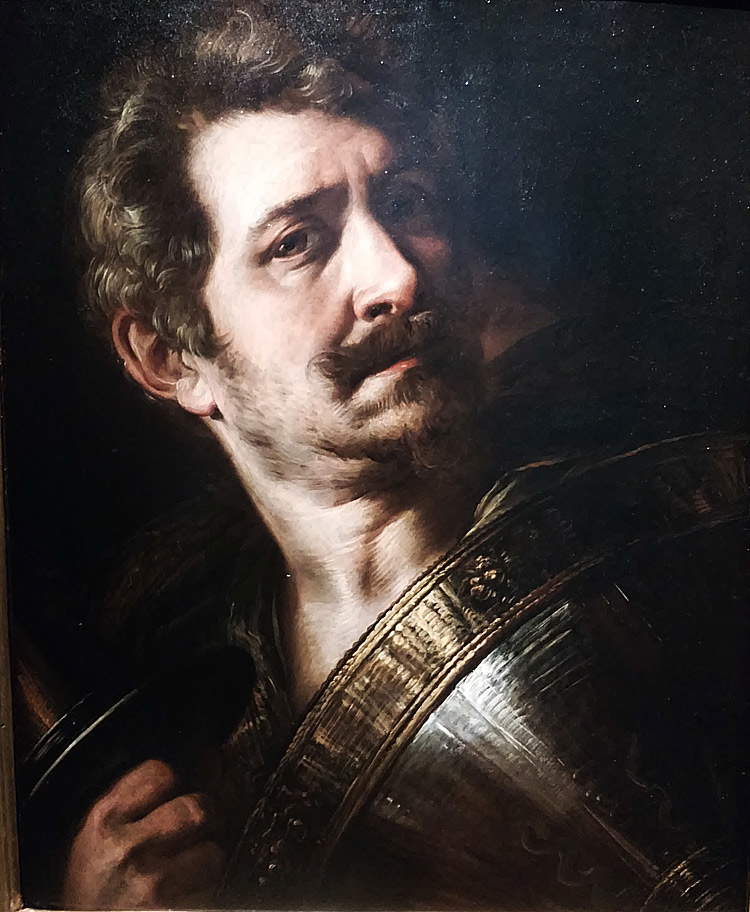

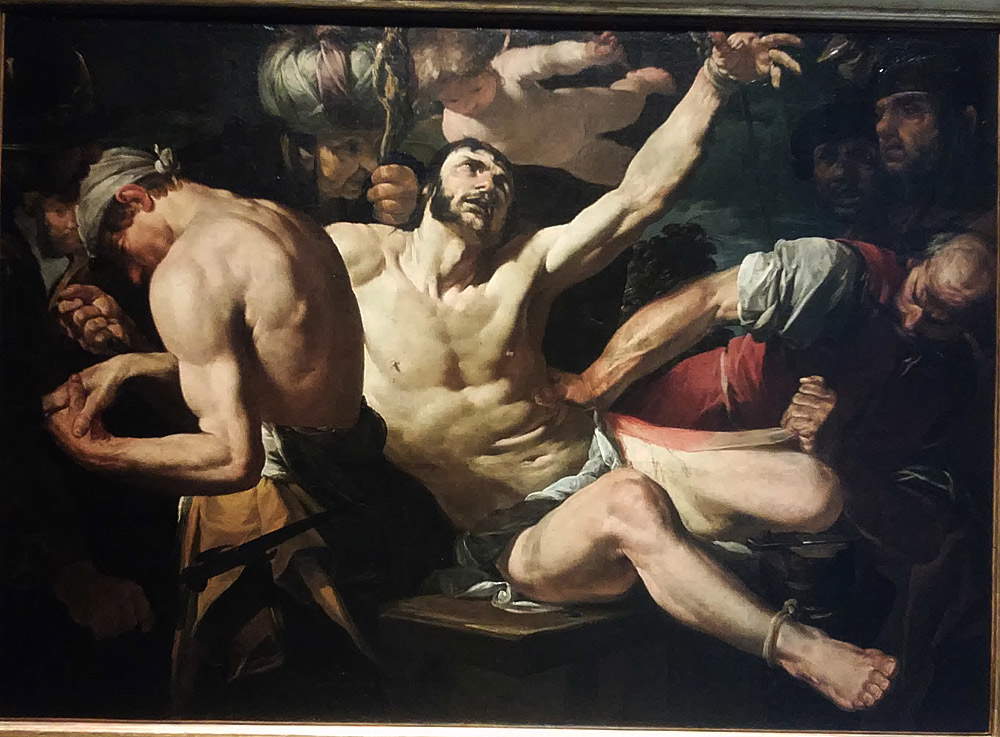

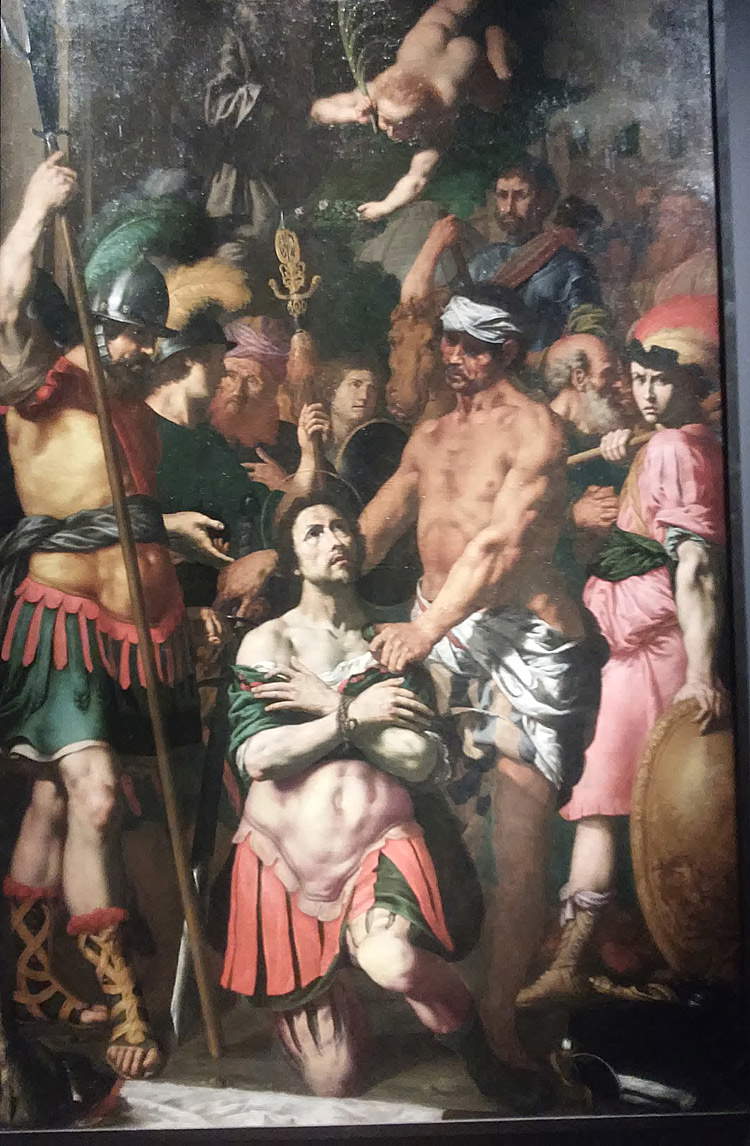

If Marco Antonio Doria was particularly active in the Neapolitan market, his brother Giovanni Carlo (Genoa, 1575 - 1626) looked instead to the Milanese scene, introduced in the third section of the Milanese review. Giovanni Carlo Doria, Morandotti again writes in the catalog, mostly loved “the virtuoso painters who then marked the transition between Mannerism and Baroque.” among them, Giulio Cesare Procaccini, presented here, in addition to two marvelous self-portraits showing him to us at about the age of 28 in one and 42 in the other, by the powerful Transfiguration executed between 1607 and 1608 for a Genoese patron, Cesare Marino, related to that Pirro I Visconti Borromeo who invited the Procaccini family to Milan in 1587. The Transfiguration is one of the earliest demonstrations of interest in Rubens’s art (the first in northern Italy, according to Morandotti), it is an important milestone on the path toward the Baroque, and in the exhibition it dialogues with aCoronation of Thorns by Cerano in turn placed in direct comparison with the macabre Martyrdom of St. Bartholomew by Gioacchino Assereto (Genoa, 1600 - 1649), on loan from the treasure trove of masterpieces that is the Museo dell’Accademia Ligustica in Genoa: Assereto, too, cannot help but observe the results of Caravaggio’s naturalism, however, declining it according to the spectacular and theatrical outcomes of Lombard art.

|

| Battistello Caracciolo, Christ Carrying the Cross (1614; oil on canvas, 133 x 183.5 cm; Turin, Università degli Studi, Rettorato) |

|

| José de Ribera, SantAndrea (c. 1616-1618; oil on canvas, 136 x 112 cm; Naples, Girolamini National Monument, Quadreria) |

|

| Giulio Cesare Procaccini, Self-Portrait in Armor (1615-1618; oil on panel, 47 x 39 cm; Montichiari, Museo Lechi) |

|

| Giulio Cesare Procaccini, Transfiguration with Saints Basilides, Cyrinus and Naborre (1607-1608; oil on canvas, 350 x 190 cm; Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera) |

|

| Gioacchino Assereto, Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew (c. 1630-1635; oil on canvas, 120 x 170 cm; Genoa, Museo dellAccademia Ligustica di Belle Arti) |

The Gallerie d’Italia exhibition does not fail to offer the visitor some decidedly exhilarating passages: we find in particular in the fourth section a double confrontation, the first between Simon Vouet (Paris, 1590 - 1649) and Giulio Cesare Procaccini, in the room where the sumptuous and celebrated Portrait of Giovan Carlo Doria on Horseback by Rubens is also exhibited (which ideally dialogues with the portrait of his brother Marco Antonio, executed by Justus Suttermans, and exhibited in the room dedicated to Neapolitan painters) and the second again between Bernardo Strozzi and Giulio Cesare Procaccini. In the first case, the dialogue is functional in showing visitors the evolution of the style of an artist like Vouet who, having divested himself of the deep Caravaggesque vein that had characterized him until his stay in Genoa in 1621 (eloquent is his David with the head of Goliath, made in Genoa but considered by some to be Vouet’s most Caravaggesque painting), around 1622 executed a St. Sebastian treated by Irene that looks to the Lombard painters (Procaccini, Cerano, Morazzone) that the French artist had been able to admire in the collections of his Ligurian patrons. The second comparison, on the other hand, compares two Madonnas by Strozzi and Procaccini to show us how the Genoese painter did not completely abandon his naturalistic impulses, while the Lombard was now totally projected toward Rubensian horizons.

It will be Procaccini’s painting, moreover, that will dictate the lines of the developments of Genoese art in the seventeenth century: the section devoted to “touch painting” intends to demonstrate this assumption by relating some interesting works by the painter born in Bologna (observe in particular the Madonna and Child from the Capodimonte Museum and the Flight into Egypt from the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna) capable of reflecting also in Genoa the great Emilian tradition of Correggio and Parmigianino (the latter another great touch painter): Procaccini’s works painted almost instantaneously with rapid brushstrokes and slight strokes, those “spots” that appeared to be sketches but were actually born as autonomous experiments (and moreover requested by patrons) had a considerable weight in the training of the young Valerio Castello (Genoa, 1624 1659), the great genius of the Genoese Baroque who is featured in the exhibition with a Madonna of the Cherries from a private collection.

The exhibition touches its most theatrical climax with the display, preceded by its sketch, of Procaccini’sLast Supper, made for the refectory of the convent of Santissima Annunziata del Vastato in Genoa and later moved (with consequent adaptation of the architectural backdrop) to the church’s counterfaçade. An enormous nine-meter canvas, restored for the exhibition, still mindful of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, with the apostles and saints “parading before our eyes in a spectacular array of portraits of disheveled old men” and which “are now ready to become a true genre repertoire within that special type of room painting, the head of character, which was just then beginning to find European fortune” (so again Morandotti). Heads of character that we find again punctually in the next section, where Procaccini’s intense saints are compared with those of Rubens and where Strozzi on the contrary establishes a relationship with the figures of Anton van Dyck. The exhibition concludes with what the curator calls the “Caravaggesque blaze” that swept Genoa in the 1640s: the aforementioned arrival of Stomer’s night-light paintings that shocked local circles far more than Caravaggio’s Saint Ursula had done thirty years earlier. It is also necessary to give an account of how the exhibition aims to reconsider sharply (although it will be necessary to assess how far such a downsizing can go) the legacy of a deity of Genoese art such as Luca Cambiaso (Moneglia, 1527 San Lorenzo de El Escorial, 1585), seen by most critics as a forerunner of seventeenth-century trends: Morandotti argues that, “with everything going on in Genoa in the early decades of the seventeenth century,” Cambiaso’s echoes faded inexorably, and that it was rather Stomer’s nocturnes that provided cues to artists such as Gioacchino Assereto and Orazio De Ferrari (Voltri, 1606 Genoa, 1657), protagonists, along with the Genovesino (real name Luigi Miradori, Genoa?, c. 1605-1610 - Cremona, 1656) whose Martyrdom of St. Alexander is exhibited (although his activity was concentrated in Piacenza and Cremona more than in Genoa), of a kind of Caravaggio revival that was short-lived, however, since the latest trends were already pointing toward great Baroque painting.

|

| Pieter Paul Rubens, Portrait of Giovan Carlo Doria on Horseback (1606; oil on canvas, 265 x 188 cm; Genoa, National Gallery of Liguria at Palazzo Spinola) |

|

| Justus Suttermans,Portrait of Marco Antonio Doria (1649; oil on canvas, 121 x 98 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Simon Vouet, David with the Head of Goliath (1621, oil on canvas, 121 x 94 cm; Genoa, Musei di Strada Nuova - Palazzo Bianco) |

|

| Simon Vouet, Saint Sebastian Cured by the Widow Irene and dallancella (c. 1622; oil on canvas, 246 x 174 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Giulio Cesare Procaccini, Beheading of the Baptist (c. 1608-1610; oil on canvas, 244 x 178 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| The comparison between Giulio Cesare Procaccini and Simon Vouet. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Giulio Cesare Procaccini, Holy Family (c. 1620-1625; oil on panel, 159 x 113 cm; Milan, Private Collection) |

|

| Bernardo Strozzi, Madonna and Child with St. John the Baptist (1620-1622; oil on canvas, 158 x 126 cm; Genoa, Musei di Strada Nuova - Palazzo Rosso) |

|

| Giulio Cesare Procaccini, Madonna and Child with an Angel (c. 1613-1615; oil on panel, 36.5 x 31 cm; Naples, Museo di Capodimonte) |

|

| Giulio Cesare Procaccini, Flight into Egypt (c. 1606-1607; oil on canvas, 40 x 21 cm; Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale) |

|

| Valerio Castello, Madonna of the Cherries (c. 1645; oil on canvas, 91 x 70 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Giulio Cesare Procaccini, Last Supper (1618; oil on canvas, 490 x 855 cm; Genoa, Basilica of the Santissima Annunziata del Vastato) |

|

| Matthias Stomer, Saul Has Samuel Summoned by the Witch of Endor (c. 1639-1641; oil on canvas, 170 x 250 cm; Private Collection. Courtesy Robilant+Voena) |

|

| Luigi Miradori known as the Genovesino, Martyrdom of Saint Alexander (1630-1635; oil on canvas, 288 x 182 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Gioacchino Assereto, The Death of Cato (c. 1640; oil on canvas, 203 x 279 cm; Genoa, Musei di Strada Nuova - Palazzo Bianco) |

The idea of setting up an exhibition that contains Caravaggio’s name in the title and then, in a way that it would not be daring to call provocative, comes to the conclusion to affirm that it is possible to find, in the history of art, some alternative paths of development, divergent from Caravaggio’s instances, is as interesting as ever, especially when one considers the fact that we are literally overwhelmed by initiatives that stake everything on the name of Caravaggio, now seasoned in every possible sauce, yet almost forgetting that there were areas that, even immediately after his death, remained refractory to his lesson. The exhibition certainly does not deny that several Ligurian painters were fascinated by Caravaggesque naturalism, but the latter was never able to profoundly affect the course of Genoese art, which instead preferred to look to Milan (another center that never matured a Caravaggesque line, despite being the birthplace of Michelangelo Merisi) and Flanders, and develop instead a full, spectacular and swirling Baroque art that found its peaks in artists such as Valerio Castello, Domenico Piola, Gregorio De Ferrari, Giovanni Battista Carlone, and Grechetto. These are issues that struggle to impose themselves on the general public, subjugated as they are by the heavy and pressing Caravaggesque marketing, and above all they had not yet been summarized in such a timely manner in an exhibition focused on these subjects.

Admittedly: the exhibition does not pretend to go into extreme detail into the artistic events of seventeenth-century Genoa, which were so complex as to make it seem impossible to summarize them in an exhibition of only fifty works, such as the one set up at the Gallerie d’Italia in Piazza Scala. But it certainly represents a good breath of fresh air within a panorama that has often proved excessively celebratory towards Caravaggio: to the rhetoric of absolute genius, to monographic exhibitions that do not allow works of comparison, to the usual tripe that almost always insists on the same topics, The Last Caravaggio opposes a review made up of dialogues, intersecting stories, apparently secondary events, and hypotheses destined to cause discussion. All this is complemented by arrangements that in certain passages become even spectacular (two moments above all: the comparison between the three Martyrs of St. Ursula and Procaccini’sLast Supper ) and by a good catalog on which stand out the sharp introduction by Morandotti, the summary of the events of the Doria brothers compiled by Piero Boccardo, and the “defense” of Genoese Caravaggism by Maria Cristina Terzaghi. It can therefore be said that the provocation succeeded and delivered us a high-level exhibition, which will most likely continue to be talked about after the closing date.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.